A white guy with a wooden leg, Joe Morgan rose to the top of California’s fearsome Mexican Mafia gang.

The Güero Loco of Kingpins

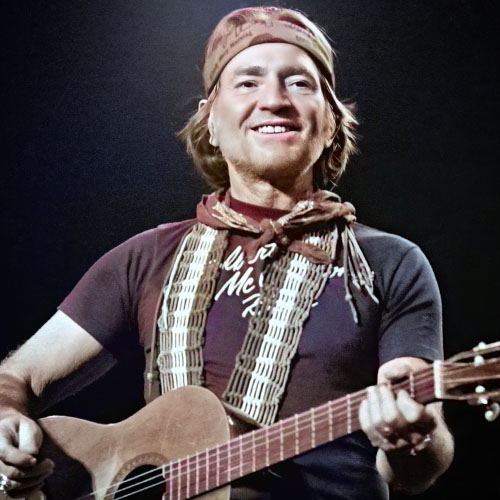

There a scene in the 1992 movie American Me where actor William Forsythe, who plays J.D., a Slavic-American character based on the legendary Mexican Mafia gang leader Joe “Pegleg” Morgan, hits a California prison yard as a newbie and is confronted by white inmates.

J.D. responds in fluent Spanish. Moments later, a group of Mexican-American gangsters roll up, glare at the “peckerwoods,” and embrace J.D. as one of their own.

As the scene extends, one of the Latino inmates questions Santana, the gang’s shot caller, about J.D. hanging with them. Santana kills the issue by letting the dude know this Anglo was one of them, a homeboy with heart, courage, and discipline.

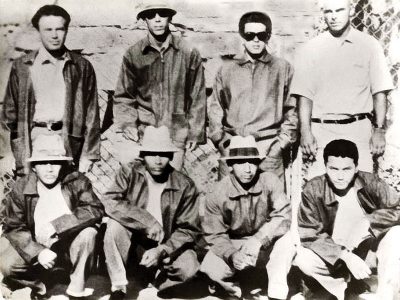

“Pegleg” Morgan — born Joseph Megjugorac in 1929 in Los Angeles, the son of Croatian immigrants — rose to become a real-life shot caller in the vicious Mexican Mafia gang, founded by 13 Mexican-Americans in a California youth prison in 1957.

This crew, also known as La Eme (Spanish for the letter M), rapidly gained in size and strength, using intimidation, extortion, and murder, both inside and outside the California prison system. Controlling territory, trafficking drugs, and terrorizing anyone who resisted their demands or threatened their power, La Eme became a dominant, entrenched, moneymaking force throughout the Golden State. And as its lethal footprint expanded, its Slavic-American player became one of the most powerful gangsters in the United States.

“Joe Morgan was a nails-tough Croatian who grew up in a Hispanic neighborhood in East L.A.,” says true-crime author and Gangster Report founder Scott Burnstein. “In total, he spent 40 years locked up for crimes ranging from bank robbery to homicide. He escaped jail twice, committed murders like he had a license, and developed, for La Eme, lucrative, power-boosting connections to both Mexican drug cartels and the Italian mafia in L.A.”

With his shaved head, burning eyes, dark eyebrows, and prosthetic leg (a result of being shot by cops while on the lam), Morgan had the right look to match his steely character. He

was smart, ruthless, charismatic, strategic, and lived by strict rules — a code he expected his associates to live by, too. Morgan, who died in 1993, helped spearhead the Mexican Mafia’s evolution into the baddest prison-spawned gang to ever do it —

a California kingpin with a big vision and ceaseless drive, a killer whose lengthy leadership status within La Eme puts him in

the conversation with marquee gangsters like John Gotti and Pablo Escobar.

“Although Slavic ethnically, Morgan adopted Mexican ways and spoke Spanish perfectly,” recalls Richard Valdemar, a Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department gang investigator for 33 years, now retired. “As a kid, he joined one of the Maravilla gangs in East Los Angeles. He’s unusual because he’s a white boy who grew up in the projects. If you met him and hung out with him for just a few moments, you’d forget he was white, though. Joe didn’t fake it.”

Despite being a güero — a light-skinned person — Morgan had a bone-deep connection to L.A.’s vato loco underworld, its subculture of Mexican-American street gangs and gangbangers. He developed a command of Mexican-Spanish slang. Raised in the barrios, he was a Chicano at heart, a guy who identified as Mexican-American, and who also, from early on, happened to be one of the baddest motherfuckers around. By his late teens, he stood well over six feet tall, and projected an intense, intimidating vibe. In 1946, still just 16, he took up with a 32-year-old married woman, Elvira Rojo, who eventually offered him $1,000 to kill her husband. Morgan did the deed early one September morning, walking into the room where Rojo’s 52-year-old husband was sleeping and bashing his skull with a hammer. He transported the corpse into the Malibu hills and buried his victim in a shallow grave.

“While awaiting trial for murder in the L.A. County Jail, Morgan keyed in on his cellmate William Westbrook, another 16-year-old who was being transferred to a juvenile forestry camp,” says Chris Kasparoza, author of the mob novel For Blood and Loyalty. “Morgan posed as Westbrook and escaped, making it no shock that he went on to become a leader in what the government has alleged is the most dangerous prison gang ever.”

“While awaiting trial for murder in the L.A. County Jail, Morgan keyed in on his cellmate William Westbrook, another 16-year-old who was being transferred to a juvenile forestry camp,” says Chris Kasparoza, author of the mob novel For Blood and Loyalty. “Morgan posed as Westbrook and escaped, making it no shock that he went on to become a leader in what the government has alleged is the most dangerous prison gang ever.”

How did a teenager hoodwink prison staff and actually gain his freedom for a time? In an early display of his craftiness, brains, and daring, Morgan studied Westbrook’s mannerisms, practiced his signature, and threatened his cellmate’s life if he didn’t go along with the young killer’s ruse. When guards came to transfer Westbrook to the camp, Morgan impersonated his cellmate and Westbrook stayed silent. After forging his signature on a booking slip, Morgan, sans handcuffs, got into a car with a probation officer.

At San Fernando Boulevard and Colorado Street in Glendale, Morgan jumped from the car, took off, and escaped. The sheriff’s department didn’t realize a cold-blooded homicide suspect had gotten away until hours later. The young criminal was now a fugitive, a wanted man, and he made page two of the Los Angeles Times with his ballsy escape.

It was the beginning of Morgan’s outlaw legend. And unlike many prison escapees, this canny 16-year-old from the mean streets of East L.A. wasn’t immediately recaptured.

“They got him a couple weeks later,” says Christian Cipollini, an organized-crime historian and founder of the site Gangland Legends. “Cops got a tip on his whereabouts, and when they showed up, Morgan took off. An officer shot him in the leg, shattering bone, and stopping Morgan in his tracks. Due to complications, his leg was amputated just below the knee and Morgan ended up with a prosthetic. That led to the authorities and media dubbing him ‘Pegleg,’ although prison lore holds no one ever called him Pegleg to his face.”

Convicted of second-degree murder, Morgan was sent to Folsom State Prison instead of a juvenile facility, due to his “criminal sophistication,” as the judge put it. Despite being the youngest inmate to ever hit the yard, Morgan received mad props at the prison, where he served nine years. With his story and Elvira’s photo in the newspapers often, Morgan became a jailhouse celebrity. (To his fellow prisoners, having sex with an attractive woman twice his age was a grand caper.)

Gangster Report’s Burnstein picks up the story from here.

“In July of 1955, Morgan was paroled, but he wasn’t out in the world for long,” Burnstein recounts. “On November 30, 1955, he robbed a West Covina bank of $17,000 with a machine gun. The FBI arrested him at a bar in Long Beach a week later. He was sent back to state prison — a convicted murderer, bank robber, and escape risk.”

When Morgan was apprehended following the bank heist, the Los Angeles Times headline read, “Hammer Slayer Held in $17,000 Bank Hold-Up.” The press coverage reminded everyone that the same guy who walked into a bank with a rapid-fire weapon like some kind of golden-age gangster — John Dillinger, say, or Machine Gun Kelly — was the teenage Romeo who took a hammer to the head of his married sweetheart’s husband.

Incarcerated at San Quentin, Morgan continued to build his criminal legend. Though in terms of daily prison life, Morgan was known for conducting himself as a gentleman around jailors and fellow prisoners, when it came time to enforce or expand his gang’s power, he could flip a switch, and — like Dr. Jekyll becoming Mr. Hyde — become capable of killing someone with his bare hands or otherwise do what was needed to get the job done.

Despite the prosthetic leg, he was not limited much physically, and was one of the better handball players on the yard, an aptitude which only added to his status.

At meals, Morgan sat with Latino prisoners and formed ties with those who would form the core of the Mexican Mafia. He became a mentor of sorts to members of the newly born La Eme, teaching them how to do time at San Quentin.

“Joe had a reputation from the start at San Quentin, because his homeboys in Maravilla were probably the largest segment of incarcerated gang members,” says retired investigator Valdemar. “If someone called him a white boy, he would have killed him. He knew what his genes were, but his heart was Chicano.”

A natural-born leader, Morgan influenced La Eme before he became a member. “He became the new gang’s first counselor and later its business guru,” says crime expert and documentary filmmaker Al Profit, director of the American Dope series. “He studied Aztec history and formed solid relationships with gang carnales like ‘Hatchet’ Mike Ison and Ruben ‘Rube’ Soto. Back then, prisoners tended to settle their disputes with their fists. But when La Eme came along, they started making and hiding weapons in strategic places on the yard, so they could grab them when things jumped off.”

On February 24, 1961, after being subpoenaed to act as a witness in the trial of a man who murdered a San Quentin inmate, Morgan masterminded an 11-man escape from the L.A. County Jail using lock-picking tools and hacksaws hidden in his artificial leg. The inmates made their getaway through a pipe shaft. Again Morgan made the news. A splashy front-page Los Angeles Times story called it the jail’s largest escape ever.

“Talk about street cred and cleverness,” says Christian Cipollini, commenting on the jailbreak and Morgan’s resourcefulness in bringing it about. This time Morgan remained at large for a week before being captured at a store in West L.A.

“When he walked back onto the yard in San Quentin, he was a California prison legend who’d escaped more than once and had served 14 years, mostly at Folsom. He learned the Aztec language and taught others so they could communicate in code. He was a master negotiator, an expert on doing time, and had connections with all the racial groups.”

“La Eme formed at D.V.I. — the Deuel Vocational Institution — a California youth prison that housed the state’s most violent teenage inmates,” says Chris Kasparoza. “Legend has it that it was the brainchild of a then 16-year-old Luis ‘Huero Buff’ Flores, who brought together the toughest, smartest, most dangerous members of various Mexican-American street gangs at D.V.I., mostly from the barrios of East Los Angeles, uniting them. It was like a ‘special forces’ of teenage gang members who ruled their youth prison yard.”

It wasn’t long before these first La Eme soldados were transferred to maximum-security adult prisons like San Quentin, with prison officials hoping the transfers would kill the fledging Hispanic gang in the cradle. That didn’t happen. La Eme members recruited even more ruthless and murderous Mexican-American inmates into their ranks, and learned lessons about criminality, organizing, and securing power from people like Morgan.

“The Mexican Mafia did not materialize in the streets, it formed within prison confines, probably out of necessity. Like virtually any other prison gang, these guys needed to stick together to survive and thrive,” says Cipollini. “The idea soon morphed into creating not just a gang, but a super-gang. Eventually that evolution created vast outside connections and reach, but of course that kind of expansion also produced enemies.”

In 1969, at the age of 40, Morgan was sponsored by his friend “Hachet” Mike Ison and joined La Eme, becoming the organization’s first member with non-Mexican blood.

Morgan was given the Aztec name “Cocoliso” and was immediately accepted into the inner circle. Up until that point, he’d been acting in an advisory capacity. Embracing his role as a Mexican Mafia soldier, he proposed operations and began scheming from day one.

“La Eme was founded on the principle that every man is equal and the gang operated on a one-man/one-vote, majority-rules system,” says Al Profit. “Leaving their individual rivalries in the street, the top gangsters merged into a single crew. Joining required a formal sponsorship. A made member had to speak up for the individual being considered for membership and take responsibility for them. La Eme was recruiting gangsters with serious criminal résumés who weren’t afraid to use violence as an intimidation tool.”

In addition to being fearless, intelligent, and ambitious, Morgan was willing to kill when and wherever for La Eme. In the pen they say, “Boys fight and men kill.” La Eme gained a reputation for killing with abandon. Side by side with all the violence, though, there was an emphasis on mental discipline, thinking ahead, and studying.

Morgan, especially, believed in the benefit of hitting the books. Determined to be the best gangster he could be, he pushed his brothers to read classics like Machiavelli’s The Prince and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War to gain insights into maintaining power and battling enemies.

Other books Morgan encouraged La Eme members to read were Grey’s Anatomy, to learn about the body and its vulnerabilities so as to maximize damage in shank attacks, and primers on martial arts and weapons. Morgan wanted to exploit every possible advantage, from knowledge of murder methods to big-picture strategizing, in his quest to make La Eme the dominant gang force in the California prison system and on the streets.

“For a long time, there’d been a close association between the Aryan Brotherhood and the Mexican Mafia because they have the same gang enemy — the Black Guerrilla Family,” Cipollini of Gangland Legends points out. “It was the Mexican Mafia who first challenged the BGF. But La Eme was also battling with another, newer Hispanic gang, Nuestra Familia. About the time that Joe Morgan came on the scene, the BGF and NF formed an alliance. The lines were drawn in the sand. That took things to a whole other level.”

In 1972, there was a bloodbath in the California system. Thirty-six prisoners were killed that year and gang experts believe the Mexican Mafia was responsible for 30 of the killings. Race riots raged at Folsom and San Quentin. There were constant, major conflicts between black and Latino inmates. It was sparked by a La Eme hit put on a BGF soldier at San Quentin. In Chris Blatchford’s The Black Hand, Rene “Boxer” Enriquez says that Morgan was good for at least a dozen murders on his own and had engineered many more.

“All the members were expected to put in work,” says former gang investigator Valdemar. “They called it ‘putting in work’ or ‘wetting your steel.’ When I say work, I mean murder. If you hesitated, you fell from grace. Every one of them put in work and they were reluctant to pass on work to anyone else. The gang was basically a bunch of prolific murderers. Prisoners like Morgan knew the system. He let people like me run the overt system, but he ran the covert. Overtly, they were cooperative with us and knew we controlled the walls, but inwardly, they operated covertly and controlled the inside.

“He was in custody in the L.A. County Jail when I worked there,” Valdemar continues. “Like 1972-73. He was in my module, the high-power module, where all the big people from the Aryan Brotherhood, BGF, Mexican Mafia, and some political guys, like Black Panthers, were. I had direct contact with him on a regular basis. I also ran the law library which inmates were allowed to visit. He was very polite. He would greet me in Spanish. The guys at the top back then, they had a smooth, know-how-to-do-time kind of attitude, but they were dangerous.”

“La Eme seized control of the flow of narcotics into San Quentin,” says Niko Vorobyov, author of Dopeworld, a new book about the international drug trade. (See our interview with Vorobyov starting on page 104.) “And as gangmembers were transferred out, they did the same thing at other prisons. Joe Morgan had La Eme getting protection money from incarcerated Italian Mafia members, along with running all the prison hustles. More importantly, he started laying the foundation for the organization on the outside.”

Beginning in 1971, in another brazen La Eme initiative, recently paroled members of the gang began taking over federally funded drug and alcohol programs in East L.A. barrios, and some community action groups as well. The moves provided income fronts for ex-con gangbangers, always ready to do the gang’s bidding (strict, across-the-board obedience to the directives of La Eme shot callers was and is an ironclad rule, and the punishment for leaving the gang is death), as well as opportunities to siphon off government money. Gang revenue streams were expanding.

Over the years, as Valdemar’s career in law enforcement progressed, Joe Morgan’s name kept popping up in various investigations, but during most of this time, he remained in custody. In other words, Morgan was pulling strings from inside the belly of the beast, issuing directives, cementing La Eme power. This was a gang and a kingpin with reach.

One of the strategic moves Morgan helped guide was establishing the pact with the Aryan Brotherhood, known as the AB. “He was a liaison,” Valdemar remembers, before adding, “but the AB had a close relationship with all the Mexican Mafia members.”

Elaborating on Morgan’s personality and approach as a La Eme shot caller, Valdemar offers this: “I would say he’s one of those people that commanded your attention. If he was in the military, he would have been a leader. He wasn’t loud. He wasn’t boisterous. He didn’t try to inflict himself on anyone else. He just quietly took command.”

The Mexican Mafia has no official hierarchy. Unlike the sprawling Latin Kings gang, they don’t bestow titles and don’t elect “Coronas” to rule the organization. Mexican Mafia members rise to de facto leadership according to what’s needed at the time and who’s in power. It was law enforcement that labeled Morgan a godfather. But in truth, he was just a loyal member of La Eme who took charge to benefit the gang — and had the help of several equally powerful members who backed him. Morgan was a natural leader, so he took on a leadership role.

He knew his clout. He didn’t need an official title.

“To rise to the pinnacle of La Eme, as a güero no less, he must have been one smart, devious, bad motherfucker,” says Chris Kasparoza. “But also a loyal, charismatic one, with a code of honor. There was a reason why so many alpha-male murderers deferred to him, and even the cops tasked with locking him up were impressed. Morgan could get people to calm down. He was a diplomat in a certain sense.”

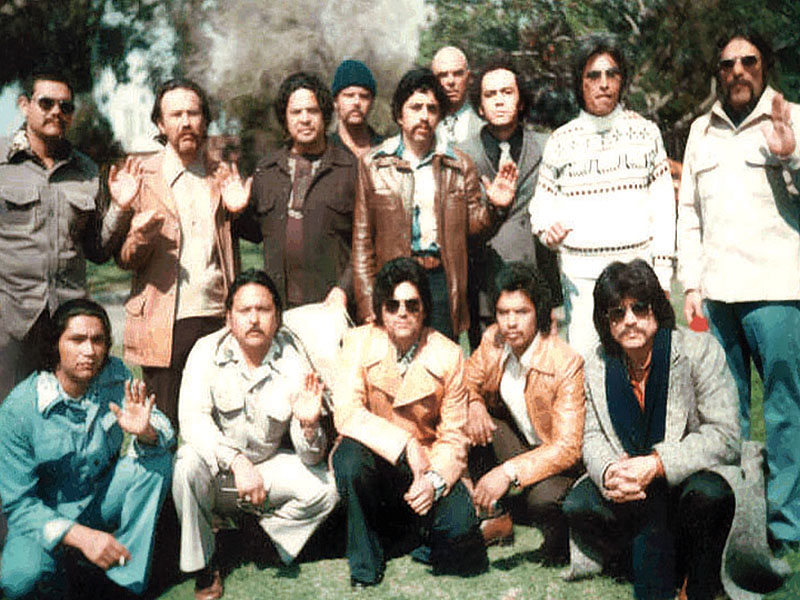

“His main allies,” says Al Profit, “were Ramon ‘Mundo’ Mendoza, Robert ‘Robot’ Salas, Alfred ‘Alfie’ Sosa, and Edward ‘Sailor Boy’ Gonzales. With these hard-core brothers, Morgan implemented La Eme’s decrees on the streets, which led to more power inside the prison system. During this part of the 1970s, the Mexican Mafia would become well-known all over California. All the Mexican street gangs paid tribute to La Eme. The organization’s name spread fear. Along with the brotherhood’s growth, of course, is the fact that law enforcement was getting hip to the gang and who their leaders were, in and out of prison.”

As his power grew, Morgan developed enemies and detractors within La Eme.

“Two OGs — Reymundo ‘Bevito’ Alvarez, who murdered a BGF shot caller, and Ernest ‘Kilroy’ Roybal — schemed against this rising soldado,” says Christian Cipollini. “They insisted that no one should be in La Eme who wasn’t Latino. They didn’t like Morgan, but Morgan had too much clout. He was paroled from Folsom in 1971, and when he hit the streets there were dozens of La Eme members on the outside as well. Morgan set about to try and organize the brothers into a cash-producing criminal enterprise.”

This Anglo shot caller wanted to “spread the Eme gospel.” Along with longtime friend Rodolfo Cadena, he launched a strategy of leveraging the organization’s power inside prison to control territory in the wider world.

Says Gangster Report’s Burnstein: “The ‘If you own the inside, you can own the outside’ philosophy grew La Eme to epic heights. Morgan’s contributions to the gang’s expansion were invaluable. Not only did his connections to narcotics suppliers catapult the Mexican Mafia into being instant, major players in the California dope game, his skills as a gangland politician paid dividends in the form of alliances and business relationships with other criminal factions — the Italian Mafia, Aryan Brotherhood, outlaw biker gangs.”

Morgan came to the conclusion that a lot of La Eme members, when they hit the streets, were obsessed with settling old scores instead of benefitting the organization as a whole. He envisioned the gang getting into more profitable endeavors. He knew murder had its place, but he wanted to use violence to further La Eme’s ends instead of securing personal revenge. As early as 1973, California newspapers were identifying Morgan as the leader of the Mexican Mafia. He couldn’t stay out of prison, though. He was always going back on parole violations.

Then in 1975, out on parole, he was indicted on federal narcotics charges and fled to Utah. He remained on the loose until July of 1977 when he was captured, and a charge of trafficking firearms joined the drug charges and fugitive warrants. A year later, he was sent back to prison for being a felon in possession of a firearm and heroin possession.

“Morgan and other top La Eme members were part of a new generation of drug lords that didn’t answer to the Italian Mafia,” says Niko Vorobyov. “They made their own connects, getting heroin straight from the source. Before, the main smack track to the States ran through the Italians, who got it from French refineries and the Middle East. But as that route started drying up, it was time to look south of the border. Poppy’s been grown in the hills of Sinaloa in Mexico since the nineteenth century. And the connections that Morgan put together in prison allowed La Eme and their street affiliates to start moving Mexican black-tar heroin in the seventies.”

Morgan had ample heroin connections. He was known as a guy who could get weight. In time, a childhood friend hiding out in Mexico, Harry Gamboa Buckley, raised in the streets of Maravilla, introduced Morgan to Jesus “Chuy” Araujo, head of the Araujo drug cartel.

Shortly after Araujo became Morgan’s main supplier of heroin, Morgan let everyone in Southern California’s criminal underworld know that if they were in the dope business, they had to sell Mexican Mafia dope. Refuse to do so and you were hit. As in murdered.

“Morgan considered the gang’s financial condition the most important aspect, but other brothers didn’t share his opinion,” says Scott Burnstein. “With made members in every major southern city in California, Morgan knew that La Eme was sitting on a gold mine. Morgan envisioned La Eme being like the Italian Mafia.”

Morgan advocated for a situation where he and other Mexican Mafia leaders functioned as Carlo Gambino or Lucky Luciano types, calling the shots while the soldiers did the dirty work, and counting the money all the way to the bank.

In the late 1970s, gang hit man Mundo Mendoza, having embraced Christianity, became a government informant. Morgan had no idea that one of his trusted confidants was actively working against him, playing ball with law enforcement. Mendoza testified that Morgan was responsible for ordering multiple murders both inside prison and out on the street. He implicated Morgan in the murder of Robert Mrazek, a La Eme associate, who was shot to death in 1977. Prosecutors presented evidence that Mrazek’s wife Helen asked Joe Morgan to kill her husband. According to a 1993 Los Angeles Times article, the La Eme kingpin first asked Mendoza to do the hit (the paper called Mrazek a “suspected Seal Beach drug dealer”). Mendoza claimed Morgan supplied him with a photo of Mrazek, his house key, and a .45-caliber pistol stuffed in a brown paper bag.

Ultimately, the execution was handled by La Eme member Arthur Guzman, who, along with Morgan and Mrazek’s wife, were all sentenced to life in state prison.

The year was 1978. Joe Morgan would never see the streets again.

“I was housed on the same tier with Morgan at Folsom during the mid-1980s,” an individual known as Serious Steve tells Penthouse. “What immediately struck me was how the guards treated him with a civility and deference I had not encountered before in prison. Morgan had him some presence. He was a strongly built person a head taller than most of the other carnales and was cat-quick on the handball court. He was fluent in like four languages and could speak intelligently on most any subject. A charismatic, charming individual. And very intense, to say the least. When Joe Morgan spoke, everyone listened. I never heard anyone refer to him as Pegleg.”

Criminal turned writer/actor Edward Bunker also got to know Morgan at Folsom, though decades earlier, during Morgan’s first Folsom incarceration.

Bunker — who played “Mr. Blue” in Quentin Tarantino’s 1992 film Reservoir Dogs, and inspired the bank-robber character Nate, played by Jon Voight, in Michael Mann’s Heat — called Morgan the “toughest by far” of all the men he met during his 18 years in prison.

In his 2001 memoir, Education of a Felon, Bunker writes: “When I say ‘the toughest,’ I don’t necessarily mean he could beat up anyone in a fight. Joe only had one leg below the knee…. He was still pretty good with his fists, but his true toughness was inside his heart and brain. No matter what happened, Joe took it without a whimper and frequently managed to laugh.”

When the movie American Me was released March of 1992, it elevated La Eme’s national profile, not unlike the way Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather brought the Italian Mafia to the pop-culture forefront in the early seventies.

People who might have thought of La Eme as merely a violent California prison gang, if they were familiar with the Latino brotherhood at all, now saw it as bona fide criminal syndicate with reach and power.

However, members of this secretive organization, including Joe Morgan, were not at all happy with the movie’s fictionalized chronicle of their gang’s birth and ascent.

And this anger had director and star Edward James Olmos, who played Santana, a shot caller inspired by the iconic La Eme cofounder Rodolfo “Cheyenne” Cadena, fearing for his life, talking to the FBI, and seeking a permit to carry a concealed weapon.

“I want to show there’s a cancer in this subculture of gangs,” Olmos told the Los Angeles Times in 1991, addressing his reasons for making American Me. Hoping to demythologize the La Eme world so as to discourage disaffected young Mexican-American men from joining the gang, Olmos created a harsh portrait of gang existence, with scenes of abuse and extreme violence. But what got Morgan and his crew mad were other aspects of the movie. In American Me, the Santana character is raped by another youth in a juvenile facility, and later Santana is shown being impotent with a woman.

Moreover, older and wiser Santana is eventually killed by his gang brothers for having doubts about their bloody enterprise. But in real life, Cadena was murdered by members of the Nuestra Familia gang, La Eme’s bitter enemies. In a gruesome hit that set off rounds of prison payback murder, “Cheyenne” Cadena was shanked multiple times and thrown off a tier at Chino State Prison, only to be shanked again when he landed.

To members of La Eme, Olmos’s movie stained their honor.

And payback followed here, too. At least it sure looked like it did.

Within weeks of the movie’s release, two of its consultants were murdered execution-style. Just 12 days after the premier, a 53-year-old La Eme member who’d spoken to Olmos during his research interviews was gunned down by a pair of gang hit men in the Ramona Gardens projects in Boyle Heights, a La Eme stronghold.

Within weeks of the movie’s release, two of its consultants were murdered execution-style. Just 12 days after the premier, a 53-year-old La Eme member who’d spoken to Olmos during his research interviews was gunned down by a pair of gang hit men in the Ramona Gardens projects in Boyle Heights, a La Eme stronghold.

Then in May, 49-year-old gang-intervention counselor Ana Lizaragga, a paid technical adviser with a small part in the movie, was slain by a pair of ski-masked hit men in her Boyle Heights driveway, shot in front of her boyfriend as they packed up their van for a trip. One of the assassins, a La Eme prospect, had just been paroled from Folsom.

In August of the following year, another unpaid consultant to the film was slain in his car. A member of a local La Eme affiliate gang was sent to prison for that hit.

Law enforcement pointed out that all three victims had displeased La Eme for reasons other than cooperating with the movie, and so were careful about calling the executions “payback.” Lizaragga, for example, who’d lost her own husband and two nephews in gang shootings, was suspected of being a snitch. But the timing of those first two hits, especially, is hard to ignore. A Chino prison official told the Los Angeles Times that the killings were meant as a message for Olmos. He also received veiled threats from gangmembers.

“When they made American Me,” says Richard Valdemar, “they actually approached Joe Morgan and supposedly got unofficial permission to make the movie as long as he hired Mexican Mafia advisors. And Olmos did in fact do that. But that meant he put himself under the rules of the Mexican Mafia.”

A month after the movie opened, Morgan filed a lawsuit seeking $500K in punitive damages from Olmos, Universal Studios, and others connected to the film. Morgan contended that filmmakers didn’t have permission to use his story and likeness in creating the J.D. character, an Anglo gangmember from East L.A., fluent in Spanish, with a shaved head and prosthetic leg. The case was eventually dismissed. But ever since the ordeal faced by Olmos (who made the cover of Time in 1988 for his Stand and Deliver stardom), Hollywood has been understandably leery about new Mexican Mafia projects.

Joe Morgan died of liver cancer in November 1993, in a hospital ward at Corcoran State Prison, where he’d been transferred from Pelican Bay State Prison, having spent his final months and years confined in an 8-by-10 cell 22-and-a-half hours every day.

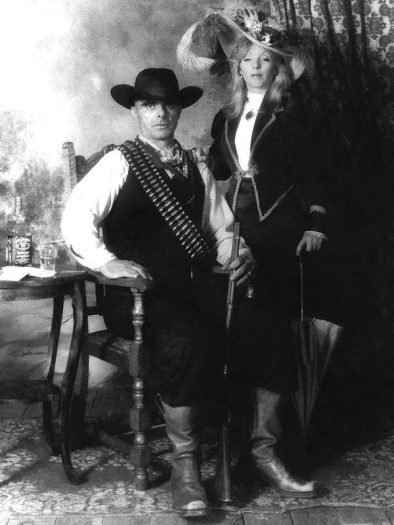

He was 64, and left behind a wife, Jody, and two children.

In his 2012 memoir Mexican Mafia: The Gang of Gangs, Ramon Mendoza describes Morgan as the “coldest, most calculating, and brutal son of a bitch you could ever encounter.” But he was also, Mendoza adds, the “funniest, most compassionate, and witty person one could ever hope to know.”

This complicated, one-of-a-kind prison gangster, who went hard and was instrumental in turning the Mexican Mafia into a dominant American gang, carries a legendary charge in the annals of organized crime. Part of Morgan’s legacy is still very much alive — La Eme continues to control the great majority of Latino gangs in Southern California, and has affiliate tentacles all over the country. A vast network of Sureños — Mexican Mafia foot soldiers — remain ready to do the bidding of their prison shot callers.

As for the movie Morgan helped inspire, retired gang investigator Richard Valdemar remembers something else that happened during the tense weeks after its release.

Concerned about the murders of Olmos’s East L.A. gang consultants, William Forsythe, who played J.D., called up Valdemar and said, “Hey, am I in trouble?”

Valdemar replied, “No, they love you. They think you’ve played him to perfection, so you’re not in trouble.” Valdemar himself thinks Forsythe did an excellent job.

“In fact,” Valdemar says, “the scene where he’s walking into court with the leather jacket on, if I didn’t know that was the actor, I would have thought that was Joe Morgan.”

Just a small correction is needed.

Hatchet Mike Ison was actually not Mexican, either. If memory serves me, he was born Japanese but lived like a Chicano.