“BUSTER, NO! BUSTER, SIT down!”

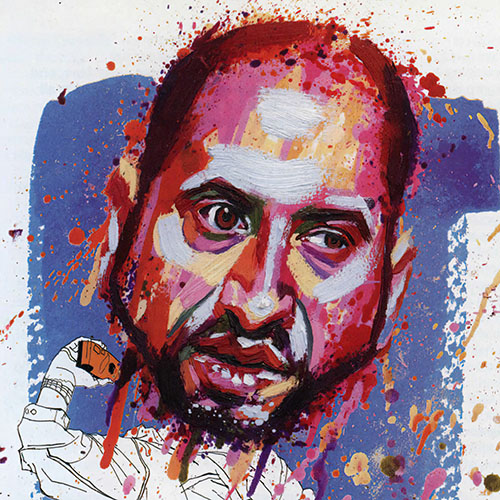

Red Hot Anthony Kiedis

Buster, Anthony Kiedis’s four-month-old ridgeback, is goofy with excitement when his master enters their Hollywood Hills home. Buster has no idea his master is a Red Hot Chili Pepper, but the pooch’s behavior is not unlike that of a lot of young and not-so-young girls who get all creamy when they see Kiedis in person. Kiedis’s dark hair, streaked blond, is short these days, his tattoos (including his latest, a tiger on his forearm) lend him a Maori look (which may make him comfortable when he visits the house he bought some years ago in New Zealand), and his gait is smooth and confident. But when it comes to slobbering young dogs, Kiedis is a stern taskmaster. That’s what the trainer at Buster’s obedience school told Kiedis he had to be. Otherwise, Buster would be chewing on table legs and pissing on carpets. And until Kiedis takes the next step and starts having kids of his own with his tall, blonde soul mate Yohanna Logan (whom he met in 1998 while she was working at New York’s trendy Balthazar restaurant), this is the closest he’ll come to being a dad.

His own dad (who changed his name from Jack Kiedis to Blackie Dammett for showbiz reasons) is visiting from his lakeside home (which Kiedis bought him) in Rockford, Michigan. Looking slim, hip, and edgy, Dad is chatting with a pretty younger woman in a corner of the living room. Dammett visits his son a few times a year, during which they hang out at Venice Beach or double-date at trendy restaurants. A former filmmaker and actor, Dammett lived in Los Angeles during the freewheeling sixties and seventies. After the breakup of his parents, Anthony lived with his mom, Peggy, in Michigan until he was 11, when he moved to Los Angeles to live with Dammett, who introduced him to weed, women, and song.

His father also turned Anthony on to acting. When Sylvester Stallone was looking to cast someone to play his son in F.I.S.T. in 1978, 16-year-old Anthony got the part. That same year, when a weird kid was needed to play a future Nazi in The Boys From Brazil (starring Gregory Peck and Laurence Olivier), Kiedis was that kid. And when Patrick Swayze and Keanu Reeves needed someone to fight with in Point Break (1991), there was Anthony once again. But the movies were never the main vehicle for his artistic expression. Music was.

“Corporations seem to be psychologically impaired as a result of the [terrorist] attack. That won’t stop us from rocking the fuck out, and we will play live wherever we feel like it when the time is right.”

And a very good thing that has turned out to be. After hitting gold in 1989 with their fourth CD, Mother’s Milk, Kiedis and the Chili Peppers went on to rack up platinum with Blood Sugar Sex Magik (1991) and One Hot Minute (1995). Their last CD, 1999’s Californication, went quadruple platinum, selling 12 million copies and garnering their best overall reviews to date. And their new CD (still untitled as we go to press) promises to further solidify their standing as one of the most influential rock-‘n’-roll bands in America.

During our interview, Kiedis appears thoughtful, composed, reflective, and in total control. Sitting meditatively in his upstairs living room, with a Warhol painting on the wall and a big-screen TV opposite a white couch, the 39-year-old scarcely resembles a former drug addict who’s had his share of run-ins with the law. He doesn’t dwell on the past, but he’s willing to talk about it. Ask him for a quick history of the band, and he’ll happily recount the members’ fledgling efforts while attending Fairfax High School in Los Angeles; their grungy beginnings playing small clubs, when they were called Tony Flow and the Miraculously Majestic Masters of Mayhem; and how they combined the names of ancient blues and jazz groups — Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, Jelly Roll Morton and the Red Hot Peppers, Chilly Willy and the Red Hot Peppers — to come up with the name Red Hot Chili Peppers. Also up for frank discussion: the 1988 overdose death of his best friend and original Chili Peppers guitarist Hillel Slovak; the five turbulent years with Dave Navarro; the brilliance of John Frusciante, who has returned to the band after disappearing for half of the nineties; the ineffable weirdness of bass player Flea (born Mike Balzary); and the reasons why drummer Chad Smith is the band’s true anchor.

These days Kiedis makes enough money to not have to worry about money, and he shares what he makes with his family, his friends, and causes he believes in. He’s hoping to build a new house in L.A. and to sell the one he has in New Zealand, which he bought when he thought New Zealand was the most beautiful place he had ever seen. And when it’s time to chill, you’re likely to find him swimming with sharks, skydiving, boxing (he once fought an exhibition with Oscar De La Hoya), or riding his motorcycle way too fast. He’s also a die-hard Los Angeles Lakers fan and a serious art collector.

Hang around Kiedis long enough and you come away feeling healthy. Maybe it’s the green tea, ginseng, and Chinese-herb concoctions he offers you to drink. Or the talk about what’s right for the planet and what’s wrong with those who are screwing up the environment and don’t care for the land and the people. It’s almost as if Kiedis has some Native American medicine-man mojo in him. You walk away from his house feeling somehow cleansed. Which is a very strange feeling to have when you remember that this is the same guy who zaps his hair into a mohawk and jumps around onstage wearing nothing but a sweat sock over his genitals, singing about finger painting with menstrual blood. Then it dawns on you. Of course: the rock star as shaman. Anthony Kiedis as holy man.

“Libido, sexual desire, frustration, all forms of sex, from the physical to the spiritual — it’s always been an active ingredient in what’s going on with us.”

A month before the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York, the Chili Peppers canceled a concert in Israel for security reasons. How has what happened in New York and at the Pentagon on September 11 affected you, and how might it alter any future touring plans?

I can’t say that [the band] had a collective reaction to the terrorist attack on America. We all dealt with the aftermath in our own ways. Flea thought about moving to Australia, Chad was rather reserved with his comments, John wanted to carry on and use our creative energies to fill the air with something beautiful, and I felt a combination of those feelings. Will it affect what we do? At our core level of working to make music, the answer is no. We get together and give opportunity to our creative spirit to thrive like we always do. As to how our music circulates through the population at large, there may be changes. Corporations seem to be psychologically impaired as a result of the attack. That won’t stop us from rocking the fuck out, and we will play live wherever we feel like it when the time is right.

It’s been more than two years since the huge success of Californication. What was it like to get back to work on your new album?

We had taken enough time off so that we were really hungry to play — get in the lab and mix up the chemicals. The songs are different than anything we’ve ever played before. There are songs that are painfully funky, and my test for that is how my dog Buster reacts. I do a lot of writing in the kitchen with him nearby. When Buster gets excited, when he wants to dance, then I know we’re on to something.

One writer described your sound as more complex in structure than punk, less uniformly beat-driven than funk, less arty than fusion. How does that go over with you?

That makes sense to me, but that’s still leaving it very wide open. One of the really great things about being in this band is that we have no limitations and it still makes sense. We can play anything we want and it fits in perfectly with everything we’ve ever done. We can write something completely hardcore punk rock or we can write something soft as soft can be, a beautiful little ballad, or we can get phat and fucked up and funky and sexy and dirty and wet and just oozing, and it’s all Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Flea has complained about “all this angry, screaming metal now. This funky sound with rapping and guitars has been turned into something very boring-right-wing, redneck bullshit.” Is this the way you feel about a lot of bands today?

There’s a lot of stuff that I hear on the radio or on TV or at halftime of a sporting event and it’s like, Jesus Christ — the kids today are really getting short-changed. I hope they can get turned on to something cooler than that. But rather than trashing that which sucks and is lame, I’d rather create something beautiful. I’d rather make as much good music as possible — then, I’ve done my job to combat bullshit.

You’ve said that your music is basically about your lives, and that you’re part of a dying breed. How so?

There is a certain amount of realism in the music we make that is not so common in a lot of popular bands these days. We write our own songs. A lot of bands have other people writing their material and a producer who’s producing you so you can get on the radio or on television, so that you can be part of a genre or a category. That way, it’s not going to be an honest form of expression to begin with, because you’re trying to be something that can get over. We don’t do that.

Flea said in 1989, “We’ve played some of the most innovative music of the eighties and I’d like to be recognized for it.” Do you think you have been?

I don’t think anyone heard our music enough to recognize what we were playing in the early eighties. People recognize us now much more for what we did in the nineties.

You once described rap as the punk rock of the nineties. Would any other music of that decade fit in to that category? And what about this new millennium?

Nirvana, Fugazi, Nine Inch Nails and electronic music — that was all also the punk rock of the nineties. When I say “the punk rock of,” I mean the revolution of … the something new of … the something that goes against the current and fights against the watered-down commercial music that is only written to fit into a radio format. Something that comes on and doesn’t sound like anything else. We are desperately in need of that, and are waiting for that to happen today.

Is that up to the Chili Peppers or does it have to be someone new?

I think it’s always up to us to some degree, but it has to be somebody new. Bands like the Beastie Boys, Rage Against the Machine, and Fugazi are always doing something beautiful, that they believe in, that defies trends or what is currently the commercial craze.

In what areas would you say the Chili Peppers have been pioneers?

We were early in creating the combination of hard-core funk with hip-hop, rap-style vocals in a live-band context. We became, maybe, an inspiration to Limp Bizkit, Kid Rock, Linkin Park — all these other bands that are doing that now. Today when we write music we don’t sound anything like we did. So we still feel like pioneers because we’re not bowing down to the system.

Your videos attract a lot of attention. How important are they?

They’re very important, because A., they’re a great opportunity to make a really cool little short film that goes along with your song, and B., they show the world what you’re up to.

Which are your favorites?

“Give It Away” [from Blood Sugar Sex Magik] is probably the best video we ever made. But “Californication” and “Other Side” [from Californication] are also high on my list.

Gus Van Sant [Good Will Hunting, To Die For] directed the video for “Under the Bridge” [from Blood Sugar Sex Magik]. Was that the first time you worked with a movie director?

I had actually auditioned for him years earlier for a film. I was so fucking high, I had been up all night and I showed up to this interview out of my mind, barely able to form words — it was pretty embarrassing. When we worked together on the music video, he remembered, and he was incredibly non-judgmental about it.

Wasn’t Spike Lee also interested in working with you guys?

We kind of blew it with Spike. He pitched us on a video idea either for Mother’s Milk or Blood Sugar, I can’t recall which. Flea was really into it, but I didn’t get it. We kind of missed our window of opportunity to work with Spike because ever since when we’ve gone back and said, “Hey, let’s make a video,” he hasn’t had the time for us.

The Beatles made terrific movies. Have the Chili Peppers ever considered making a movie?

Yeah, we’ve always wanted to do something like A Hard Day’s Night and have never succeeded. I think we may have missed that window as well.

But you have appeared on The Simpsons. Where does that rank in your list of achievements?

The Simpsons is one of the greatest television shows in the last 15 years, and I love Matt Groening’s work. I was so happy he came along and knocked all these hokey family sitcoms out of the water. So when they asked us, it was a no-brainer. Their animation style doesn’t go for realism. You get the big fat over-hanging lip and one or two recognizable traits; they also got our tattoos upside down and backward. But I give them an A for effort.

How many bands would you say you’ve influenced?

A lot, but I find it counterproductive to give it attention. I don’t care about other punk-funk garage bands we’ve given birth to.

Are there any rivalries between you and other bands?

Back in the day, we always had this thing with the Beastie Boys, where they were East Coast and we were West Coast. Our music sounded a lot different, but I always felt there was this weird competition. I hope they did, otherwise I was imagining things. We’ve had other rivalries, but I feel there’s enough to go around for everybody. I don’t have to worry about getting mine.

You’ve certainly gotten yours, and you’ve also spread some of it around to causes you believe in. How many benefit concerts do you play in a year?

Lots. We took a percentage of our last two years of touring and put it aside, and at the end of two years we had this huge chunk of money — a half a million — that we divided and gave to 15 different charities, everything from research at the Huntington’s Disease Foundation to different kids’ groups — creating a positive ripple effect.

You like to emphasize the positive, but the media often goes the other way In an early song, “Funky Crime” [from The Uplift Mojo Party Plan], you wrote: “Hey you, Mister Interview / I don’t have to answer you.” Do you often get annoyed with interviews?

When we first started, we were impossible for writers to pigeonhole or categorize, so they wrote all these insulting things. Yes, they can be snide and small-minded, but sometimes they’re really fun. If there’s a band I’m into, I’m going to want to read an article about them, and I’m going to want to know what that person had for breakfast and what kind of underwear that girl wears.

And what kind of underwear do you wear?

When we go on tour, part of the deal is that we get new underwear every night from the promoters of the show. Because we sweat a lot every night and our underwear gets drenched. When we come offstage you want to have a fresh pair. So it’s really whatever the promoter provides within our specifications. It’s not a certain brand, it’s like a tight cloth boxer — everything from Burberry to Hanes.

Beats wearing only a sock, which you guys have done. How did that fashion statement come about?

I moved out of my father’s house when I was 16, and my roommate had this friend who was into me, but I had a girlfriend at the time. Still, she sent me all these pornographic cards saying come hang out. So, as a razz, when she came over one day I went in my room and put a sock over my cock and nut sack and walked out to greet her as if nothing was different — casual, like a Monty Python episode. It was actually a great phallic look. That was at a time when we were into sensationalizing our sexuality, and the next time we had one of these special shows at a strip club on Santa Monica called the Kit Kat Klub, as our encore we performed in socks. There were go-go girls dancing — we got a rush out of performing like that.

Has anyone pulled off the sock while you were onstage?

No, but people have tried. Sometimes you have a nice-fitting sock — it’s really the balls that keep it on there. Other times you have this kind of stretched-out sock and you’re in a little trouble. That’s when you stand real still, because if you start jumping around you’re going to lose your sock.

Did the sock get you more attention than you anticipated, which might have worked against your music being taken more seriously?

For the longest time, the media didn’t want to talk about anything but the shock-value entertainment portion of our program, and we just got sick of it. We wanted to be talked about for our music, not just being naked or explosive.

You’ve changed your look over the years: long hair, short hair, mohawk, blond, black, brown. What’s with that?

A mohawk gives your ass a whole lot of power. It’s a good-feeling haircut, there’s a new jolt of energy you get. It’s not like I give a fuck about presenting a new look, but it’s fun and it is empowering. But sometimes I look at old pictures and think, What was I thinking? I’ve got an artichoke on my head!

Are you more comfortable performing topless?

Yeah, it feels good when you perform as naked as possible, but I also like going out in a shirt and a tie sometimes, but I can’t stay like that for more than a song or two. It’s a very physical experience and it gets hot out there.

Let’s talk about the other members of the band. How would you describe your drummer, Chad Smith?

Chad thinks completely differently from the rest of us. We’re hypersensitive weirdos; say the wrong thing to us and we can go spiraling for an hour on “What did he mean by that?” Chad’s not like that. I don’t think we could handle it if we had another guy who was so creatively sensitive. Sometimes it’s hard to realize how incredibly important it is what he does for this band, but he really is the anchor to everything.

“It’s great having such a multitude of sexual experiences. But… I’m lucky I still even have an interest in sex.”

And Flea?

That’s a book right there. He’s the first guy I befriended at Fairfax High School, and we have really had an insanely chaotic bond ever since. Flea went to a fortune teller one time who told him, “This guy, Anthony, you have been friends with [him] for many lives. In your last life, sometime around 1930, you were on the verge of dying on the streets of Italy and Anthony came along and saved your life and gave you direction.” It feels like we have that kind of bond. I’m sure he can imagine being in a band without me, but I sure can’t imagine playing music without him.

The group has had seven different guitarists, starting with Hillel Slovak in ’83. How different were the Chili Peppers with each of these guitarists?

The real guitar players in this band were Hillel and now John [Frusciante]. This is in no way a diss to Dave Navarro, because with Dave we did record a record [One Hot Minute], we did do a lot of touring, and we did stay alive and vital, but it really was kind of a bridge between John leaving and John coming back.

Flea has said that Navarro didn’t quit and you didn’t fire him; so how did the split come about?

This was ’94-’95, when I was going back and forth between sobriety — not the most productive state of mind for a band to be in. So here you have one of the quintessential Los Angeles guitar players from Jane’s Addiction, one of the all-time greatest-loved bands. But he was coming from a band that didn’t write as a band. They wrote as individuals. As the Red Hot Chili Peppers we write very much together. That was a new circumstance for him. So he came in, I started getting loaded from time to time. The record took a long time. The chemistry never really clicked. Flea came to me one day and said, “This isn’t happening. The only way I can imagine continuing would be if we got John back.” At the same time Dave had started working on his solo record and was completely drifting into his own solo world. So it wasn’t a firing; it wasn’t a quitting. I don’t think any of us felt good about it.

Ten years ago you said of Blood Sugar Sex Magikthat it was “the greatest sense of accomplishment that we’ll probably ever know.” Still true?

No, I was wrong. Definitely the greatest sense of accomplishment was reuniting with John and making Californication after having not been together for six or seven years.

When he wanted out, were any of you there to try and convince him not to leave?

No, because he had gone insane, and as much as it troubled my heart that we were falling apart, it would have been more painful if he stayed in the band.

In “This Velvet Glove” [from Californication] there’s a line: “John says to live above hell.” How far above?

Basically it’s a much more exciting existence being sober than it is being strung out on heroin and cocaine. Heroin and cocaine are incredibly predictable and really suck the life out of you, and I think he was feeling extreme elation at having his own senses back in order and loving every moment of life, so that was my shout-out to John.

That shout comes from your own personal wrestling with drugs. How much of a struggle has it been to stay clean?

When I first started using drugs they were truly amazing and a magical, spiritual experience — a shortcut to the euphoria I was missing in my life, a solution to that awkward empty feeling inside of me. But over time, all of that initial magic disappeared. I believe now that I’ve experienced everything good there is to experience from drugs, and every time I’ve ever returned to using, it’s been a bad experience.

When did you smoke your first Joint?

I smoked pot with my father when I was 11 in 1973. He thought he was being a good father, giving me a mind-extending thing, just like he used to give me Hemingway novels and Woody Allen films and take me out and show me the world. By 12 I was taking Quaaludes and Tuinals. I was probably 14 when I sniffed my first cocaine. I started seeking out heroin and injecting it at 18 — around the time I quit going to UCLA I was going to get my education in a different place altogether.

Your best friend, Hillel Slovak, died of an overdose. When you heard of his death, did you feel that it should have been you?

I didn’t feel like it should have been me. I felt it was strange that it wasn’t me. Everyone always looked at me as the one who had the most life-threatening relationship with drugs. People were used to me disappearing for days and weeks at a time, so when the phone rang, they weren’t thinking that it would be Hillel who was dead, but me.

When you were 12 you lost your virginity to your father’s 18-year-old girlfriend. How life-altering was this experience?

Very. At the time, it seemed like I had just hit the jackpot, because all of my friends would have given their left nut for a situation like that. But when I look back at it, I think, Hmmm, kind of weird. It’s the sort of experience you want to have as far away from your parents as possible, but I got my dad to hook me up with this very sexually active girl who seemed available to me.

Looking back, was the girl treating it as a lark or did she see you as a very young stud?

Lark is a very good way to describe it. I don’t think she found me irresistible on a sexual level, she just wanted to bequeath me with a very nice sexual experience.

You have said that “having a semi-maniacal womanizer for a father had its advantages and disadvantages.” What were they?

The advantages were that of a hedonist, which I definitely was at a young age. There were so many young attractive women in our house running in the current of my father’s life that I was just exposed to many opportunities — from friendships to sexual relationships. You pattern yourself after your parent at that age, and what his life showed me was that more was always better. But I grew out of that, I didn’t follow my father’s path for very long. The disadvantage is that that lifestyle can set you up for a pattern to never really find your soulmate — to never partner off with the ultimate she-wolf and grow old together. To me, that is a more desirable experience than jumping from girl to girl.

And today, with Yohanna, do you feel you’ve found that soul mate?

Yes. What I want is a companion who knows me and knows all sides of me and is that friend I can be myself around, who doesn’t judge me, who I lay down next to. Every night I go to bed I get into the same position with my girlfriend that we’ve been getting into for years, and every night it feels like the first time we’ve ever been in that position because it feels so good. To me that’s a better feeling than being out at the club going, “I wonder about this girl, I wonder about that girl.” Yeah, it’s great having such a multitude of sexual experiences, but I’ve had a multitude of sexual experiences. I’m lucky that I still even have an interest in sex.

Who’s the last celebrity who’s told you they’re a fan of the Chili Peppers?

Tom Hanks. I was at a benefit fashion show and he came over and said, “I’m Tom Hanks and I just have to thank you for making Californication, it has given my entire family immeasurable pleasure.” Then his wife came up and was equally vivacious with her praise.

Who’s the biggest asshole among the celebrities you’ve met?

Jack Nicholson was probably the biggest asshole. But I don’t hold that against him. I approached him at a Lakers game in ’89 with the Mother’s Milk CD because it had a song on it called “Magic Johnson.” I wanted to give it to Jack to give to Magic. I was like, “This has a song on it called ‘Magic….’” “Don’t talk to me, kid. I don’t know Magic,” he says, and waves me off. I thought, Fuck, what an asshole. Later, I’d see him at the games and how people are constantly fucking with him, and I realized, what else could he do?

You met Bill Clinton not long ago. What was your impression of him?

I met him at a friend’s house. He had just gone up to Stanford to see his daughter graduate, and was glowing over her accomplishments. He talked to me for two hours; I talked to him for two minutes. I didn’t mind. It was like being in school with one of the smartest people I’ve ever met.

He could probably appreciate how you’d get inspired in the late eighties looking at posters of former teen porn star Traci Lords. What did she do for you then — and who does it for you now?

There was a time when we were watching a little bit of Traci Lords during the taping of Mother’s Milk. In fact, we actually used an orgasm track of hers for the background of one of our songs back then. Lately I get a lot of inspiration from the beauty of Radiohead’s last two records — Amnesiac and Kid A. Kurt Cobain was my favorite songwriter in the past 15 years. I was just constantly in awe of his character and of his art. I’ve also gotten inspiration from P. J. Harvey, Sinead O’Connor, artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Robert Williams.

You’ve said that communion between a female body, miniature microphones, and a guitar neck results in certain unearthly sounds that can be found on Mother’s Milk. How unearthly can it get?

That’s getting back to the Traci Lords thing. Libido, sexual desire, frustration, all forms of sex, from the physical sensation to the spiritual sensation — it’s always been a highly active ingredient in what’s going on with us. Music by the virtue of its rhythmic nature lends itself to that — the release. And melody releases dopamine, which is what heroin releases in your brain. It gives you a sense of well-being. We try to capture that which releases those chemicals in the brain, by being in tune with our own sexual selves and manifesting that in the rhythms and melodies of our music.

You open the song “Purple Stain” [from Californication] with: “To fingerpaint is not a sin / I put my middle finger in / Your monthly blood is what I win / I’m in your house now let me spin.” Are these the lyrics your fans have come to expect from you?

I feel lucky when I can write the lyrics that sound right and feel right and fit in perfectly with the music. I’m not thinking about what everybody is going to think.

Would you say you write more or less about sex today?

It’s always creeping in there. I love it when it finds its way into stuff on more subtle levels. Finger painting with menstruation blood — it’s a nice image. Kind of gets you over the fear or taboo of it.

Truman Capote once spoke of the devil residing in those who have tattoos. He found that the only thing murderers on death row had in common was that they all had tattoos. Fifty percent of people later in life want to remove tattoos. Think you ever will?

I’ve never regretted any, and I still want more. It’s beautiful to watch the tattoos grow old and fade and become like worn-in jeans. They’re all representative of times in my life, so I can’t imagine ever wanting to erase any time in my life.

Should you still find some heat in the Chili Peppers, you can visit them online. So far, Anthony Kiedis has kept on ticking. Apparently he has Unlimited Love lately.