Just how bad, in truth, can three pimply juveniles be?

Boys Just Wanna Have Fun!

The suspicion nags; There is a latent message in the Beastie Boys’ dense rap-rock. But how to discover it?

Well, hold the front of the Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill album jacket up to a mirror, and the refracted image reveals a hidden affront – the tail-section serial number of the crashed plane on the cover reads: EAT ME.

Is this the covert communication in question? Nah, just a smidgen of frathouse smut.

To get to the bottom of this lingering minor mystery, one must plumb the psychic, acoustic, and personal bramble of the Beastie Boys’ roots, the thicket of ambition that lifted this white, solidly middle-class burlesque of the ghetto’s pariah rap and hip-hop culture to the top of the nation’s record charts.

But first a word to the blissfully uninitiated. Late in 1986, the brattishly nick- named trio known as the Beastie Boys (Adam “MCA” Yauch, Michael “Mike D” Diamond, Adam “King Ad-Rock” Horovitz) issued Licensed to Ill, an unprecedented album-length amalgam of hardrock Tilt, tree-house poetry, and the appropriated defiances of underclass street rappers. It appeared on Def Jam, the aggressively peculiar new rap-speed metal-soul-and-vinegar subsidiary of Columbia Records, fabled stable of Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and Barbra Streisand. Reactions ranged widely and wildly. For some, Licensed to Ill greeted the oracles like the braying din of indefatigably lousy neighbors. Others complained that the record rang out like a Little Rascals’ Disco Night debate at the He-Man Woman-Haters Club. But a solid three million purchasers were impressed with what they heard as an inspired mixing-board bouillabaisse of hip-hop’s torrid beatbox ticktock and the tumultuous adrenalizations of early heavy metal. Moreover, the whole shrill lockstep was paced by back talk from baby-faced suburban nihilists weaned on Star Wars, the Iran-contra scam, and Gary Hart’s stained underwear.

Licensed to ill’s first sublimely loutish single, “(You’ve Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party),” went Top 10 in a big hurry, and the LP itself not only swiftly notched the No. 1 slot in the U.S.A’s sales surveys, but became the fastest-moving product in its record label’s illustrious history. Two more hits, “Brass Monkey” and “She’s Crafty,” ensued.

Now the growing fear among detractors is that the Beasties’ expanding following is as puerile, brash, and mutinous as its heroes’ music.

A new generation of rock and funk fans, faced with parents who often buy the same Prince albums they do, may well have rushed to embrace the Beastie Boys as something only they can love. The Beasties’ comically cacophonous cant is a splenetic homage to beer shooters, suckerpunching, all-night fornication, angel-dust hors d’oeuvres, and horseplay with firearms. Interspersed with all the obnoxious raillery are lifted snippets of vintage Led Zeppelin, Steve Miller, and Aerosmith guitar riffs; muddy excerpts from the theme of the bygone “Mr. Ed” television sitcom; guttural antigay rhetoric-plus other sonic snapshots of the scrap heap of civilization. Depending on the attitude of its devotees, Licensed to Ill is either a turntable parody of eighties teen rebellion, or a tape-deck checklist for a curbside Gomorrah.

In the larger world, the less def, i.e. , hip, homemakers and town fathers of America shrug heavily and turn a deaf, i.e., disinterested, ear to the clamor – until they catch their kids repeating snatches of the doggerel soliloquies (of, in this case, “The New Style”) that pass for lyrics “Father to the many/ Married to a nun/ And in case you’re unaware, I carry a gun… I got money in the bank / I can still get high / That’s why your girlfriend thinks that I’m so fly’ … I got money and Juice/ Twin sisters in my bed / Their father had AIDS so I shot him in the head’”

Dismay has escalated as the Terrible Trio has begun to make stage appearances across the heartland, spraying Budweiser on spectators, scratching their crotches distractedly as a dumpy go-go dancer wriggles in an elevated cage beside them, and mumbling between-numbers repartee that gets quoted in “The Cribdeath, Iowa, Gazette” “How many songs have we done? . Only two?. Sorry, I smoked all this opium before. If anybody wants to buy some, talk to the girl up there behind bars.”

Once again, as PTA groups howl and the music press winks, rock ’n’ roll has a lot of explaining to do. But how bad, in truth, can three pimply Juveniles be if they could appear on ’American Bandstand” and Joan Rivers’s “Tonight Show” rip-off without shattering either program’s scripted decorum? Hell, even Vanna White recently went backstage to meet them and lived to speak about it.

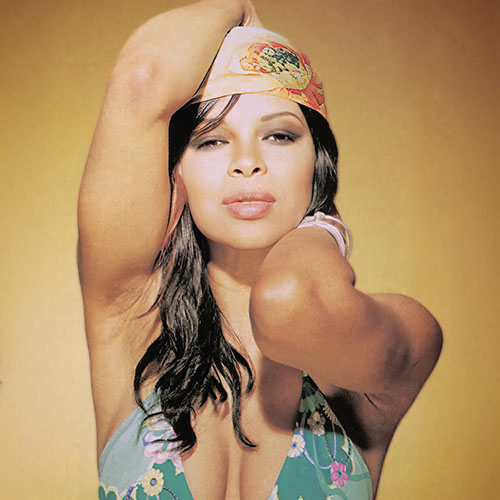

Every generation has its varieties of junk rock, purple pop, and raunch roll. In the fifties, there were the Hot Nuts, dark lords of the college-fraternity circuit. In the sixties, the Fugs and the Mothers of Invention took the wonderfully filthy Pigmeat Markham-pre-TV Redd Foxx approach to topical burlesque and ran it through an electronic biker-hippie encoder. Meanwhile, jive-speak monologuist Melvin Van Peebles kept the lunatic fringe of soul and R & B grandiloquently honest with the do-rag declamations of his brilliant Brer Soul LP

Come the seventies, George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic crew had everybody babbling to a daffy downbeat. As the eighties arrived, Jamaican reggae toasters and dance-hall deeJays helped trigger the inner-city Cool Herc-Kurtis Blow rapping that the Beasties are now bending to their own silly will.

Thing is, all of the aforementioned the aberrant art. There wasn’t a poseur, dilettante, or slumming moonlighter in the bunch.

The present mission, then, is to discover if the Beastie Boys are strictly Jake, or simply an increasingly Blade Runnerstyled society’s answer to the Banana Splits (four live-action animal characters named Snorky, Bingo, Fleegle, and Drooper whose surreal-cute rock ’n’ roll band was a staple of Saturday-morning TV from 1968 to 1970-and they made albums, too).

This summer, the Beastie Boys barnstormed the States in two flamboyant phases (before dropping from sight to film their first star vehicle, tentatively titled Scared Stupid). The first leg of their road show included new Def Jam artists Public Enemy, the sinister two-man voice of the sub-slums’ ominously emerging denizens. The second strike, which was entitled the Together Forever Tour, was shared by veteran colleagues RunD.M.C., macho rappers of the black middle-class variety.

The European sprint of the Together Forever Tour was marred by heated backstage fighting (Beasties’ management depicted it as a “tiff”) between the Boys and Run-D.M.C. at Switzerland’s Montreaux Festival. Arriving in England, the Beasties were banned by the British Holiday Inns, and Adam “King Ad-Rock” Horovitz was arrested May 30 at a West London hotel for his alleged role in a bottle-and-beer-can-throwing incident before 3,000 fans at their concert earlier that evening. Four kids were reportedly injured and five collared by police in the show-canceling melee at the Royal Court Theater, at which the waggish audience chanted “We tamed the Beasties’” King Ad-Rock was ordered to return to London in midsummer for a court appearance. All in all, the two joint international concert treks made for a disquieting spectacle.

Catching up with the Beasties cavalcade at its halfway mark, the Boys themselves appeared to be distinctly isolated from the mechanisms that ballyhooed their remarkable commercial beachhead. As such, the meeting proved an ideal opportunity to scrutinize the three supposed malcontents at close range, in order to determine precisely what they had to offer by way of content, offense, and pretense.

It’s perfect weather for a hanging, or a hip-hop siege. An unrelenting assault of rain, flooding, and funereal gloom has moved New England officials to ask President Reagan to declare assorted states of emergency in the region, which would qualify afflicted areas for federal disaster relief. As a consequence, citizens of the traditional cradle of revolutionary democracy are in a tangibly edgy mood as the bad boys of rap invade their terrain.

Looming before a two-thirds-capacity crowd at the Providence Civic Center in Rhode Island, a supporting member of Public Enemy’s act keeps a machine gun trained on the largely white teenage throng, while featured rappers Flavor-Flav and Chuck D spew boastful bile about gang violence (”My Uzi weighs a ton!”) and the pleasure of misogyny (snidely admonishing the “Sophisticated Bitch” of the song title that she deserved to be beaten “till she almost died”). This is black rap at its grimmest, an invitation to dance on tombstones and tenement corpses. A punk-thrash combo called Murphy’s Law does a short set to clear the air, but they grate on already frayed nerves. By the time the headlining Beastie Boys are introduced, the faithful in the front rows look even paler than the acutely pasty-faced Boys themselves. It’s Saturday night, but everybody’s too bummed to boogie.

Several days onward, the Beasties troupe rolls into the Worcester, Massachusetts, Marriott at three in the afternoon for a 9 PM. stand at the local arena. The three young stars, looking peaked from knit-together nights of postconcert partying, are roaming around the corridors of the bland motor hotel, desperate to elude a German rock writer, his wife, and the CBS International press agent who is squiring them around.

“She’s such a bitch’” yowls MCA, 22, an unshaven pug with broad shoulders and a hard stare, as he ducks into his room, slamming the door in the faces of the CBS flack and her party.

A booming, female “Fuck you I” is heard to resonate in the hallway. MCA collapses on his half-dismantled bed in laughter, as cohorts Mike D and King Ad-Rock take seats at either end of the suite, which looks like it was redecorated with a hand grenade.

“Fuck her,” says Mike D, 20, the lanky, ache-caked Huntz Hall look-alike, who is best known for the sizable Volkswagenbus ornament suspended on a gold chain around his bumpy neck. “We should get the keys to her room later and bust in “

“Yeah, it’s room 504, isn’t it?” rejoins MCA, who is clearly the ringleader and de facto theorist of the group.

“That room might be the German guy’s and his wife’s,” warns 19-year-old King Ad-Rock, baby-faced wiseacre and ritual dissenter. “We’ll kick the door down, and she’ll have him tied up inside’”

The three grouse a bit more about what a “fucking snot” the CBS lady is, dish on various interviewers they’ve reduced to frustrated sobs, and then discuss luminaries they’ve encountered since their rise to notoriety

“We get along all right with Johnny

’Rotten’ Lydon,” MCA offers. “He’s a fucking nut Job We played on a bill with him once in Washington, D.C. Johnny is not like anybody you can actually carry on a conversation with. He Just yells and screams and dances in the hallway-”

MCA’s attention is suddenly drawn to the room’s flickering TV, which displays the Nike running-shoe ad utilizing the Beatles “Revolution.” Since the commercial licensing of “Revolution” and 250 other Beatles songs is controlled by Michael Jackson’s publishing company, the talk turns to another marginally adjusted superstar. The Beastie Boys are openly annoyed at Jackson, who recently filed a cease and desist order against Los Angeles radio station KROQ for playing the Beasties’ outre, unreleased rendition of the Fab Four’s “I’m Down “Jackson had earlier refused to allow the Beasties to include that version on Licensed to Ill.

“Michael said something to [his producer] Quincy Jones to the effect of, ’I hate the record, and I hate them,’ “ explains Mike D with a smirk, “so it doesn’t look too hopeful.”

“I wonder,” says MCA, picking a scrap of watermelon rind off a teetering pillar of room-service trays, “if Michael Jackson knows how to lick the pussy?”

“I dunno,” says King Ad-Rock, his smooth brow abruptly furrowed, “but if Michael can bend down, he can do it, right?”

“It’s bogus to use ’Revolution’ to sell sneakers,” MCA adds, “but TV is so fucking boring anyhow, I figure I can turn the picture to black and Just listen to the Beatles on network television, which is pretty def.”

Run-D.M.C. signed a deal with Adidas to pitch a line of basketball shoes. Has anybody approached the Beasties about product endorsements?

’All the time,” MCA assures, nipping at the mangy melon rind and then putting it under his pillow “We tell them to fuck off. A clothing company offered us a half-million dollars to stand there in their clothes for one minute.”

“It seems,” says Mike D, musing reflectively, “that every car commercial is Just stealing a Motown song “ And it also seems that every Mike D fan is stealing a VW hood ornament, or other brand, to wear, a national Mercedes-Benz spokesman reporting that dealers ordered 12,600 replacement ornaments this spring, nearly triple the amount sold last year

“But on the other hand,” says King AdRock, “I’d rather watch a stupid car commercial rip off Motown than watch Bruce Willis do it And I’d rather watch anything than Bruce Hornsby and the fucking Range. Actually, I used to work in a recording studio that did television commercials.”

“Yo’ We recorded ’Cookie Puss’ at a studio that was a jingle house,” MCA recalls. ’A place called Celebration. Nobody in the music industry knows about the place because it’s such a tight-ass, bullshit studio full of losers.”

MCA is referring to the creation of the Beasties’ most renowned underground effort, a 12-inch independent single released in 1983. The A-side of the record documented an actual taped phone call to an unaware counter girl at a Manhattan Carvel outlet, the caller inquiring about the ice-cream company’s nationally advertised children’s “Cookie Puss” cake novelty. The B-side was “Beastie Revolution,” a snide send-up of Rasla reggae and Jamaican deeJay toasts, complete with jaundiced patois mimicry. Creem magazine recently described the single, with curious understatement, as “seemingly sexist and racist.”

It’s a toss-up as to which track is more contemptuous in tone, but the “Cookie Puss” tete-a-tete, a gleefully offensive aping of an insolent black youth, probably wins out:

These pussy crumbs make me itch.

Maybe I should scratch. . . [Sound of an outdoor pay phone being entered and used, the dialed number ringing.]

Hello, Carvel. Yo, man! Is Cookie Puss dere?

Who?

Cookie Puss! I want ta speak ta Cookie Puss, man!

No. Nobody here by that name.

Cookie 0. Puss, den! Cookie Chick! Anybody, man. I want ta speak ta dem!

They’re not here.

I say, yo! I asked ya where’s Cookie Puss at? I’m serious. I wanna talkyo, man-Cookie Puss l Awright, lemme order one, den. Lemme get one.

When do you want it for?

Anytime, man! Jus’, like, now, an’ shit! I’m talkin’ now, mate! [There is a sharp click, then a dial tone] Damn bitch hang up! I’ll kick yo’ ass, bitch!

“Tom Carvel was gonna sue us,” says MCA, “until his nephew Kevin talked him out of it. We’re friends now with Tom Carvel’s nephew.”

“He put a good word in for us with his uncle,” says Mike D. “’Cookie Puss’ is a big collector’s item. I heard it now sells for between $75 and $100 in stores, but it never really sold all that much when we first put it out.”

“I got like eight copies of that shill” King Ad-Rock exclaims. “I could make a fortune!”

That’s what obscure rocker Rick Rubin may have assumed when he first listened to “Cookie Puss.” Regardless, he saw a perverse promise in the platter. Rubin, a graduate of Lido Beach High School, an integrated Long Island institution, had long been enamored of the G-string soul of Rick James and the Ohio Players, as well as the post-Led Zeppelin stridulations of such heavy-metal acts as AC/DC. His band, The Hose, combined these tastes into a rude blare that could have been termed “peep-show metal.”

Rubin entered New York University in 1981, and began frequenting the downtown rap night spots. He ran around with rapper T LaRock and deejay Jazzy Jay, who made a rap record, “It’s Yours,” that featured an unconventionally conventional chorus break, just like a mainstream pop record would have.

It was a glimmer of a crossover ploy, and Rubin shrewdly sensed the winds of rap were shifting-in the direction of commerciality. When “Cookie Puss,” a hip-hop salvo from a white outfit, permeated the downtown scene, Rubin sprang into action. He started the Def Jam label in Autumn 1984, headquartering it in his NYU. dorm room.

At the time, Adam “MCA’’ Yauch was enrolled at the Elizabeth Seeger School on Franklin Street in Greenwich Village, and Michael “Mike D” Diamond was attending St. Ann’s School in Brooklyn Heights. Fledgling bassist Yauch and guitarist-percussionist Diamond cofounded the original Beastie Boys in 1979 with guitarist John Berry (who named them) and drummer Kate Schellenbach. They were a marginally functional punk band when they encountered Adam “King Ad-Rock” Horovitz, a Brooklyn Tech dropout enrolled in New York’s City As School (CAS) work-study program for problem pupils. Horovitz was also head of a punk group called The Young and the Useless. While hanging out together at Stimulators and Slits concerts at such clubs as Hurrah, Tier 3, and Rock Lounge, the chums elected to turn their two bands into a semi-permanent double bill. Eventually, the three lads merged their ambitions under the Beasties banner, releasing Polly Wog Stew, a seven-inch EP on the tiny Rat Cage label in 1982. When Rick Rubin appreciated “Cookie Puss,” the sole track salvaged from an abortive studio session, the Beasties discarded their instruments in October 1983 and became rappers with Rubin (alias DJ Double R) as their stage deejay and studio Svengali.

Def Jam Records’ inaugural release was LL Cool J’s “I Need a Beat.” The Beasties’ “Rock Hard” came next Rubin took a tape of “Rock Hard” to another collegiate New York entrepreneur, Russell Simmons. The son of a Queens school superintendent, Simmons was producing younger brother Run’s rap group, RunD.M.C., while at City College. Rubin worked out a distribution deal with Simmons’s Rush Productions, and the Beasties’ 1985 “Rock Hard”/”Party’s Gettin’ Rough”/”Beastie Groove” EP became a sensation among the club cognoscenti, its invocation of “I’m a man who needs no introduction / Got a big tool of reproduction” a standard dance-floor chant

When their single, “She’s on It,” was included in the shoddy Warner Bros. rap movie Krush Groove, the Beasties’ landed a six-week slot as the opening act on Madonna’s Virgin Tour-during which they were continually booed. They fared better on Run-D.M.C.’s Raising Hell concert sweep, but that hitch was denounced nationally for the violence that plagued its venues. The excursion to promote Licensed to Ill is therefore a crucial test of the Beastie Boys’ viability as a draw

As expected, the ticket-buyers seem to be predominantly white middle-class kids, with a healthy black representation on the fringes of the halls. However, judging from the New England dates, the black faces virtually vanish after Public Enemy’s sets.

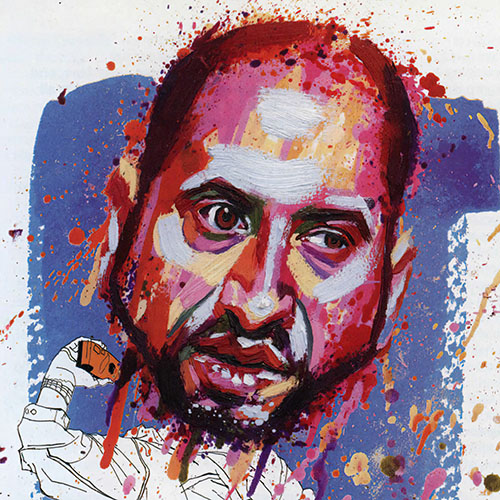

Canvassing the blacks as they leave, I am offered comments that dismiss the Beasties as “soft shit,” “white clowns,” or “corny.” Yet all bestow lavish praise on Public Enemy, whose Def Jam debut LP Yo’ Bum Rush the Show (a reference to gate-crashing), is a stark replication of underclass rage, set to a tumultuous, bleakly nonmelodic power groove. Public Enemy’s “Chuck D” Ridenhour and William “Flavor-Flav” Drayton began at Adelphi University’s radio station on Long Island, but are self-appointed spokesmen for an ultra-disenfranchised ghetto generation whose parents and grandparents have known only welfare. Theirs is less a form of entertainment than a street-theater dress rehearsal for “The Fire This Time.”

Which is why the Beastie Boys’ performances are steeped in unnerving, wholly unintended ironies. As they bound before the footlights to deliver their raucous takeoffs and cartoon recastings of authentic inner-city rappers, the audience is dealt a plethora of current catchphrases, crime colloquialisms, and drug nicknames-but no inkling of the painful realities they describe. Like the ’’Amos and Andy” radio show of a bygone era, the Beasties embody and parade fresh stereotypes of black-ghetto culture while flooding the country with a hip lexicon that whites can exploit to mocking or bigoted effect

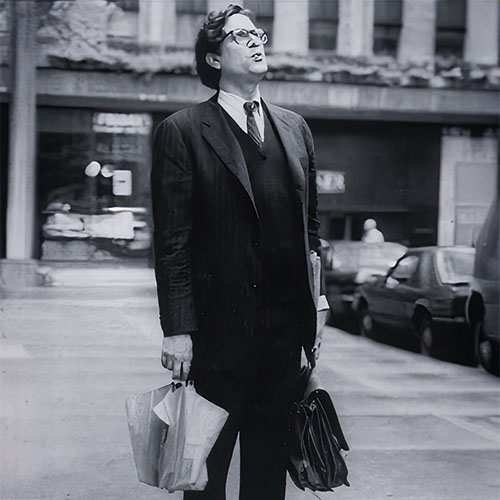

The Beasties themselves, although enmeshed in the colorful, bohemian side of eighties urban culture, are not exactly products of its mean streets. King AdRock is the son of the late Doris Keefe Horovitz (to whom Licensed to Ill is dedicated) and distinguished 48-year-old playwright-screenwriter Israel Horovitz, a Fulbright and Guggenheim fellow known for such stage and screen works as The Indian Wants the Bronx, Author’ Author’, and the acclaimed new offBroadway comedy-drama North Shore Fish. MCA’.s parents are accomplished architect Noel Yauch and New York City school-system administrator Frances Yauch. Mike D’s mom is noted interior designer Hester Diamond. The Boys’ credentials are plainly those of parental headaches from privileged households, and their decision to embrace rap was as casual as it was fashionable.

What became of the instruments the Beastie Boys once played?

“Some of it’s in my parents’ attic,” says MCA, looking uncomfortable with the question. “We used to have stacks and stacks of amplifiers, because we bought these Univox amps that sounded like shit but looked really cool onstage. It was all bogus.”

“But now it’s really cool,” Mike D ventures warily, “because we get a lot of free shit from guitar manufacturers. Adam [Horovitz] likes to say he was a guitar virtuoso, but when he Joined the Beastie Boys, he only knew one chord!”

“Give me a guitar,” King Ad-Rock protests, scanning the instrumentless room. “I’ll show you!”

“I’d just like to say,” Mike D continues. “that when we first met Adam Horovitz. hippy Adam was like, ’Look guys, there’s nothing gay about talking to plants…’”

“Look, I had gerbils as pets,” says King Ad-Rock, flushed. “That doesn’t mean I walked around looking for butt hugs. I used to go to the same places, the same clubs, as these two guys, but I hung out with people who were a lot cooler and more intelligent than these guys. I went to better schools and had more advantages than these two. The friends I had back then, we’re all friends with now The friends they had back then, we don’t even talk to.”

“I stay in touch with nobody,” MCA retorts, King Ad-Rock’s Jibe having found its mark, “ ’cause I don’t need any of them I knew they were bastards from the beginning.

’’Anyhow,” MCA continues, changing the subject, “we were getting good as a band around the time we played a show in Boston at the Rat”

“We sucked,” says King Ad-Rock, testy. “We always sucked.”

“We played a good show l “ MCA insists, pressing the point, his dark eyes aflame. “There were times when I walked out feeling happy with the show we’d played. We never sounded like fucking Aerosmith, but we were fucking good. This was in 1984.”

“It was the summer of ’62,” Mike D quips, “with the Strawberry Alarm Clock I You know-’lncense and Peppermints.’”

It’s pointed out to Mike D that the Strawberry Alarm scored that hit in the psychedelic heydaze of 1967, not the Shirelles-Four Seasons pop equinox of 1962.

“I guess,” Mike apologizes softly, “we don’t know our rock history. It’s true. We don’t.”

Such bantam bursts of vulnerability and vague embarrassment are in simmering conflict with the Beasties’ impudent public pose, an image they lack the experience and stamina to sustain.

Collected within the blank walls of this shoebox-sized room, they are tangibly lonesome in each other’s presence, starved for individual attention. Thanks to their fragile fury and its occupational focus, for perhaps the first time in their separate lives, they are not being ignored. It excites like restitution, and it tastes like revenge.

“Musically,” King Ad-Rock cracks, deftly discrediting Mike D’s confession, “we’re pre-Al Green and post-Al Lewis, the actor who played Grandpa on ’The Munsters.’ “

“It’s Just important right now, when we’re going to Lincoln, Nebraska, and wherever, that we show our rap roots,” Mike D mutters coldly, “because otherwise they stand a very good chance out there of never actually seeing a rap group.”

How, by the way, did the Beastie Boys come to compose “(You’ve Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party)” ?

“It was toward the end of the album,” says MCA, growing surly. “That was one of the last things we recorded.”

“It was summer 1986,” says Mike D. “We wrote it in about five minutes. We were in the Palladium with Rick Rubin, drinking vodka and grapefruit Juice, and ’Fight for Your Right’ was written in the Michael Todd Room on napkins on top of those shitty lacy tables. I remember we made a point there of like, ’Look, we gotta get shit done,’ and we sat at one table, really determined to accomplish something. It was just like it is now, trying to fit everything in. We have to fit our movie into this touring.”

What’s the plot of Scared Stupid?

“The plot,” says King Ad-Rock, “is Yauch gets laid, loses his virginity.”

“Yeah,” MCA deadpans, “I get a hundred blow jobs a day, but I haven’t gotten any girl to give up the pussy yet.”

There is an oddly pregnant pause, and then MCA offers a personal vignette.

“I lost my virginity in a tent in Holland, and that’s true. I was on the first day of a bike trip. It was one of those American youth-hostels trips where you’re not allowed to have sex or do drugs. I was a little dude and she was 19, big, and real def. The leader of the trip found out that we were fucking after a while, and threw her off the trip because she was older and was supposed to know better than to fuck.”

“I lost my virginity,” King Ad-Rock volunteers, “when I was at camp.”

“I lost mine,” Mike D chimes in, “in my friend’s basement. It was just one more thing I was trying to fit in.”

His cohorts groan at what MCA decries as a “Doc-and-Johnny-type gag,” and then they excuse themselves to prepare for the evening gig.

The assembled mob, nearly a sellout, are rowdier than previous recent houses, perhaps because it’s a school night out. Public Enemy and Murphy’s Law make no impression on the three-quarters Caucasian sea of restive adolescents, but when the lights go down for the main attraction, a forbidding spark is struck.

Actually, it’s a can of hair spray, which a girl in the upper balcony has turned into a torch with her cigarette lighter. She hurtles the can toward the deejay’s booth (which sits atop three towering cans of Jolt Cola), easily missing Hurricane, the six-foot-five dreadlocked blood who also doubles as the Boys’ bodyguard. Still, the effort has enough spontaneous verve to almost eclipse the onrush of the Beasties, who launch into a burping recitation of “Time to Get Ill.”

The Boys are greeted with a mighty whoop, a sizable number of onlookers brandishing their heretofore hidden Budweiser in solidarity. The Beasties respond with shaken-and-sprayed suds of their own, their hand-held mikes becoming secondary props in the sodden melee. Deejay Hurricane moves from one music track of Licensed to Ill to the next, jumping his turntable needle and supplying scratchin’ counter-rhythms with a tad too much haste.

Thirty minutes into the contrived bacchanal, the crowd roar grows dull, the collective alcohol and sugar rush spent. Their jaws slack, their eyes glazed, they appear to be reeling with the last feeling they had anticipated-boredom.

The aisles suddenly clog with kids, but the traffic is flowing in the wrong direction-toward the exits. Ten minutes more, and the subtle trickle has turned into a torrent, spectators departing in packs of ten and 20. Long before the obligatory encore, the hall is half-emptied.

Outside, the surprisingly subdued throng ambles or stumbles off into the darkness, some retrieving stashes of beer, others pointed in the direction of neighboring gin mills. Many are cold sober but clearly bemused. What’s the problem?

“Aw, we saw enough,” says one husky teenager from Charlestown, speaking for his huddled friends. “They weren’t really playing the songs.”

“There was no band,” bitches a dungareed guy from Framingham, his arm around his disappointed date. “We expected live rock ’n’ roll, not some recorded stuff.”

“Right. Check it out,” says a skinny young man from Somerville, who’s leading three blond ladies in leather and spandex. “We were up for some serious guitar and drums. Some good Jamming on the raps. We couldn’t believe it was just them and the damned sound system.”

Didn’t they realize that most rap music is merely syncopated monologues over prerecorded tracks? “They had one real band there,” the slim young man challenges, his narrow face stiffening with annoyance. “The Beastie Boys could’ve had their own musicians, too.”

“Yeah,” seconds one of his blondes, “we wanted to hear the music they played on the record. Not Just some cheap tape recording of it.”

Despite their miscomprehension, the disgruntled patrons have a point. Straight rap performances lack the musical dynamics to fully gratify an arena’s worth of people, and there’s certainly little in the essential, rote presentation to scrutinize, admire, or celebrate. Especially on this scale, the notion of live instrumental backing for hip-hop-the players primed to parry and thrust against the raps, building them into ballsy new configurations-is infinitely superior to what actually takes place. Besides, the Beasties were only going through the motions tonight, forgetting or disregarding the words to much of their material.

When confronted about the lack of genuine musical interest in their shows, the boys begin to get skittish in the extreme.

“Well, we play instruments in the studio,” says Mike D apologetically. “We really do. We’re not the Phony Boys.”

But there are no such musical credits to be found on Licensed to Ill’s album sleeve.

“Listen,” says MCA coolly, “most people don’t know it, but we coproduce and write the songs for the records.”

“We thought this whole Beastie thing up for ourselves about eight years ago,” says King Ad-Rock, “and if we make albums that everybody hates, we’ll still be happy.”

Which raises a final question. Youth culture has been bluffed and gulled before by comfortable middle-class kids who were indulging a self-important passion or a convenient nihilism. Retracing the 1960s, the bulk of a privileged generation’s political zealots disappeared into Wall Street boardrooms and “country chic” lifestyles, leaving the working class to clean up the mess.

Are the Beastie Boys indeed in rock ’n’ roll for the long haul, or will they wind up as fat corporate executives or real estate magnates, their musical career a dimly recalled dalliance?

’’As far as I’m concerned,” says MCA, his voice exploding into a rattled bellow, “I’m just gonna fuck everybody’ I wanna be an executive and a lawyer and a real estate magnate. Whattaya think, I’m naive and stupid?”

“Hey! Hey! Don’t say that!” shouts Mike D, as he shoots King Ad-Rock a cautioning glance. “Be cool, man. Are you crazy or something? Don’t tell ’em that!”

“Why the fuck not!” says MCA, on his feet, indignant. “Because it is…” He instantly reads the genuine alarm on his companions’ faces, but his pompous ire has its own momentum. And though his voice drops to a skidding whisper, it’s simply too late to stop those awful words

“…the truth.”