Within minutes the groupies (“dodgey birds,” Billy calls them) started streaming into the empty restaurant, desperately vying for tables. Soon the establishment was humming with activity.

Idol Worship

Cleveland, Ohio, said Billy Idol with relish, is a rock-and-roll outpost where groupies wait with fanatic patience for a glimpse of passing punk angels. The peroxided blond singer dressed in a shredded leather vest with cockscombcut hair recounted how he had been taking a rehearsal break with a few members of his band in a modest bar-restaurant across from the concert hall.

Female eyes ogled the lanky boy with rosebud lips. One long-legged lovely, a teenage fantasy seemingly incarnated from one of his hit singles, walked by and Billy leaned toward her and asked, “I wonder if by any chance you might be into some unhealthy sex?”

She answered him with a lurid smile.

“Great,” said Billy, with an equally lurid grin, “let’s go down to the men’s toilets.”

He stood up proudly, ready to claim this fleshy dividend of success. Winking at his drummer and keyboardist, he strutted from the table, swaggering toward the dim flight of steps that snaked down to the rest rooms. With no further word, the young woman trailed after him, gliding without hesitation through the door marked Men. As they squeezed into a cubicle together, she automatically dropped to her knees and, with Billy unzipping, spoke for the first time. Looking up at him doe-eyed, she asked, “Will you sing ‘Rebel Yell’ for me?”

Moments later, on the upper level, members of his band heard the booming “more, more, more” refrain of his Top 40 single.

Billy Idol is one of the last of a dying breed of authentic punk rockers from England. A former member of the notorious, so-called “Bromley Contingent,” which spawned sex-and-drug rockers like Johnny Rotten and the Sex Pistols, this 28-year-old expatriate who lives in New York City has developed into one of today’s most visible and easily identifiable rock entertainers. His controversial success is due in great part to his videos, which are laced with eroticized images of violence, bondage, and Satanism, and are among the most popular on MTV. For the better part of the past three years he has had three albums bouncing around the charts, as well as five hit singles.

Billy Idol’s latest hit song, “Eyes Without a Face,” smashed through to the top five, while the album Rebel Yell made it to the top six. Under the guidance of Bill Aucoin, the rock manager whose confectionary wizardry got millions of American teenagers hooked on the taste of Kiss, Billy Idol has been accused of slipping his subversive aesthetics to America’s youth.

“But I’m really too obvious to be subversive,” Billy points out. “Somebody like Wayne Newton is the one who is subversive. He’ll sing any old claptrap just so you’ll like him. He’s the one who’s really dangerous.”

It is 11 P.M. and Billy Idol and his entourage are having dinner at Carumba, a trendy, fast-track restaurant in Manhattan’s tenderloin district, where the margaritas are made to sting the senses. A young woman who has had one too many begins taunting Billy about his “ballocks.” More than a little bored with her coyness, he says, “All right, have a look at them.”

He stands up and drops his tight black trousers.

Unfortunately, the woman is not the only one to thrill at the display of Billy’s jewels. In the general commotion that follows, a large man at a table across the restaurant rushes over, forceably embraces the rock star, and plants a kiss on his cheek. As Billy struggles to break free, the table goes over and its glass top shatters. The next morning the incident makes the New York papers. It is reported that during the melee, Idol shouted, “I’m a big shot from England,” and that the man responded, “I’m a big shot from Brooklyn.” This story infuriates Billy. “I’d never say, ‘I’m English, I’m a big shot.’ If you’re English, you don’t even have to say you’re a big shot.”

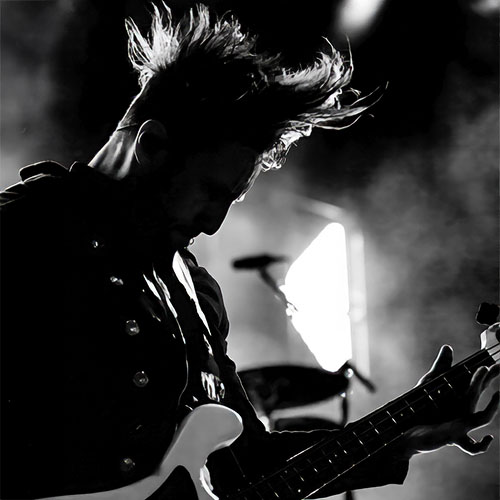

Backstage in a communal dressing room at the Warner Theater in Washington, D.C., the four other members of Billy Idol’s band have just finished donning their tattered leather garments, spiked bracelets, and studded belts, and are ready to stage the sense of rage that Idol feels is keeping us all prisoners. Tommy Price, the group’s compact, curly-headed drummer, and Steve Stevens, Idol’s guitarist and songwriting partner, are pelting each other with fistfuls of cocktail nuts. The room is raining cashews as Billy Idol strides in, fresh from shaving. His hair, newly bleached the previous evening when his punk needed to be honed for an important photo session, forms a spiked halo around the doomed patrician beauty of his face. He is decked out in his trusty nihilistic trappings: gold crucifix earrings, a large silver cross swinging from a long chain around his neck, phosphorescent rosary beads. “Fifteen minutes,” he announces in a deep, husky voice as he stalks about the room. In a moment of mischief, he reaches into a gray tote bag, rooting through face creams and torn leather gauntlets to draw out a studded leather whip. He takes a large cracking windup and flails the floor. “Oh darling, more!” cries his lovely Southern female keyboardist, Judi Dozier, while Steve Webster, the soft-spoken bass player, snickers.

The whip is a memento from one of their recent tours, thrown up onstage by an ardent 16-year-old. One of those fans “from Hewlett, Long Island, who wear those mesh shirts and rub their breasts under my nose,” Billy recalls with relish. He carries the whip with him wherever he goes, although he fervently denies charges that he is a misogynist. In Rochester, New York, this past summer, Idol, through his attorneys, pleaded guilty to a harassment charge. He was fined $250 as a result of an incident outside his hotel room last December involving a 20-year-old woman.

Suddenly, the road manager enters the dressing room to inform Billy that the band must go on almost immediately. The hall has union rules that dictate when a headliner must begin playing after the backup band stops. Delays may mean penalties of thousands of dollars. “Don’t talk to me about money when I’m about to go on,” Billy cries. “I said 15 minutes. If they want it different, I’ll cut out three songs from the end. Rock and roll has no time limit….” The room has fallen still as he turns briskly toward his band. “All right, from now on we play no more union venues. The bastards. The wankers.”

‘The girl dropped to her knees in the men’s toilet and spoke to Billy for the first time: “Will you sing ‘Rebel Yell’ for me?”’

Regardless of stage rules, the 15 minutes elapse, and finally Idol’s signature music, the theme to The Man From U.N.C.L.E., is piped through the concert-hall speakers, The band enters, prankishly carrying guitarist Stevens onstage. They withdraw to their instruments, and the set opens with “Baby Talk.” The song, Billy later explains, is about how things seemingly inconsequential can have real meaning. Although his audience is speckled with fans sporting leather gloves, studded wristbands, and punk haircuts, the majority of the crowd is young and clean-cut. Idol also attracts the kind of costume folk who sold out so many Friday-night showings of the Rocky Horror Picture Show. In the darkness of the rows dozens of white female “brides” pay homage to the main character in his most popular video, White Wedding.

As he sings his big hits “Dancing with Myself,” “Hot in the City,” “Rebel Yell,” and “White Wedding,” the crowd pummels the air with their fists. Billy’s response to his audience frequently changes in spirit. His pretty, bad-boy countenance twists, his lips curl into a snarl, as he lurch-dances through a maze of electrical cords, lyrics projecting an angry sense of rage and injustice. Hardly all personal charm and sexual provocation, Billy can get downright mean. “There’s not enough image in rock groups,” he claims. “Looking different and acting different should reflect what a band’s music is.” After all, the essence of punk has never been to please.

Guards have been hired to enforce a strict no-dancing-in-the-aisles rule, a fire department precaution. In the wings, the road manager is noticeably worried. He knows Billy will encourage the audience to dance and so risk liability. Sure enough, a moment later Idol runs his right hand provocatively over his upper left arm stroking the tattoo, “Oktobriana,” the proud female warrior who became the underground cartoon symbol of Soviet discontent. He asks his audience to throng the aisles. While the security force runs amok trying to quell the stomping teens, he raises his fist and declares emphatically, “I love you.” Later he will explain that “‘I love you’ doesn’t mean you can take advantage of me. I love but beware.”

Born the son of a traveling salesman in Stanmore, England, Billy Idol (ne William Broad) spent four years of his childhood in Rockville Centre, Long Island, where his father worked for the Blue Point Laundry. When his family returned to England, they first lived out in the country before eventually moving to Bromley, a suburb southeast of London. A conventional boy, Billy was even a member of the British Boy Scouts who roamed their local neighborhoods on “Bob-a-Jobs,” earning tips for house and yard labor, which they then gave to charity. Of this boyhood public service he recalls many customers who got away with paying him a meager shilling for a day’s worth of work. It was then that he began to reflect on the “paltriness of the adult world.” Soon after, he began teaching himself the guitar.

In 1976, a student of English at the University of Sussex, Billy made the 60-mile trek to London one weekend. There, for the first time, he saw the then current outrage of Great Britain, the Sex Pistols, play the 100 Club in Oxford Street. Miraculously, their music embodied many of his own ideas. William Broad soon changed his name to Billy Idol. (“I can be an ‘idol’ just by calling myself one — that’s how flimsy it all is.”) Along with bass player Tony James, the newly christened Idol was inspired to fire up his own group: Generation X.

Generation X was an instant sensation. They played only one live gig before they were offered a worldwide recording contract by Chrysalis’s high-rolling cochairman Terry Ellis. Their first album, called Generation X, produced an immediate hit, “Your Generation,” which was a taunting parody of The Who’s “My Generation.” Although criticized by the English music press as “teeny-punk,” Generation X was considered more upbeat in tone than the raunchy and violent Sex Pistols. They also were more pleasing to the eye — sort of pretty-boy punk. “Personally,” Billy says,

I believe punk rock is out to destroy, but in the best way possible. It was out to push aside the dross that didn’t really matter. We were out to make what didn’t matter look old-fashioned.” Leather and leather bondage were the key to this punk ethos. The bondage represented punk’s idea that we all were prisoners trying to break away; the leather was meant to be sobering, in the sense that it said, “Take us seriously.”

Things started to get shaky for Generation X during the recording of their second album, Valley of the Dolls. They had taken on a 25-year-old manager, Stuart Josephs, who, according to Idol, immediately cleared his own cut of 20 percent from the gross advances made by Chrysalis. Part of the management contract was also a service agreement, and by placing his own financial priorities first — an odd contradiction of music business etiquette — Josephs deprived the group of substantial funds for touring, which is intended to boost record sales. “Here I was making 50 pounds a week,” Billy recalls. “I kept thinkin”, ‘Where’s the big advance?’” Yet the other band members were surprisingly apathetic about their management. “It was ironic,” he remarks, “that musicians supposedly concerned with trashing everyday artistic exploitation could be so casual about their own undermining.”

It took nearly three years, half of it in litigation, to end Generation X’s relationship with Stuart Josephs, who left with a settlement in his favor of 12,000 pounds. By now the bad publicity and legal entanglements, which had prohibited the group from recording for more than two years, had virtually ruined the band. The record company had to write off a $500,000 loss.

Enter Bill Aucoin.

During the litigation with Stuart Josephs, Chrysalis asked American rock manager Aucoin if he was interested in trying to revitalize the foundering Gen X. Aucoin, a tall, misleadingly soft-spoken dynamo, listened to the group’s earlier albums with only mild interest but instantly recognized Billy’s potential to be a star. To Aucoin, Gen X itself seemed accessory. If the record company wanted to make back its advance, there was only one way to do it: Make Billy live up to his name.

Idol at first was suspicious of Aucoin, whose slick merchandising techniques seemed the antithesis of punk music. Straightaway Billy told Aucoin that he refused to do videos and be packaged and sold on television like a box of cereal. And further, he was committed to making yet another album with the band. So, according to Aucoin, he managed Gen X “in secret.”

The secret became notorious in early 1981 after the commercial failure of the group’s last album, Dancing with Myself. Abruptly Billy abandoned the band and went to New York as a solo act. Aucoin now plotted Idol’s future “basically the same way I set up things for Kiss.” Settling down in the midst of the carnival element of the East Village, Billy went to work rerecording several Generation X favorites on a mini-LP called Don’t Stop. Released in autumn 1981, the album became popular in dance halls though seldom played on the Top 40 stations.

One night Billy met unemployed American guitarist Steve Stevens in a club where Stevens had purposely hung out in order to fraternize with the Gen X veteran. Stevens was exactly what Billy needed to launch his career in the States: an American filter through which to sift his ideas. Eventually, the two began composing together. With Stevens’s help, Idol finally put together a backup band and was able to release his first solo album in May 1982. However, only one song, “Hot in the City,” hit the Top 40, and then Chrysalis’s changeover from independent distribution to CBS made the record virtually unavailable between December 1982 and February 1983.

‘One night it’s great having a wank, one night it’s great screwing some bird, one night it’s great getting a blow job. What’s the big problem?’

But Aucoin always knew that if it meant preserving his career, Billy Idol would become Billy the Idol. Strongly counseling a high-quality video, Aucoin got Chrysalis Records to shell out the 37,000-pound expense. White Wedding was made in England and directed by David Mallet, the creator of David Bowie videos. Released in February, the video was played relentlessly on MTV: hypnotic images of a bride riding in a gleaming black Rolls and anticlerical wedding scenes, punctuated with the mordant humor of toasters and water faucets — those tame conventions of connubiality — exploding. The single “White Wedding” made it into the Top 40. Music stations that had been resisting the punk were now excitedly proffering Billy Idol.

Chrysalis faced a dilemma. More Billy Idol material was needed immediately, although their artist was only just beginning to conceive his new album. After some deliberation, it was decided to rerelease the first mini-album, using its popular lead song “Dancing with Myself,” now a three-year-old tune, as the basis of a new video. At the time Billy, a great fan of the film Texas Chainsaw Massacre, was keen to exchange ideas with its director, Tobe Hooper. After a few meetings, which raised sparks between the two headstrong personalities, a working formula was agreed upon, the budget set at a whopping $80,000, and the video was created. Aired on MTV in August 1983, it steadily gained in popularity, while the twice-released single was finally able to catch a low rung on the charts.

Yet Idol’s personal polemics, as seen in the video version of “Dancing with Myself,” have aroused expressions of grave concern by the National coalition of Television Violence, the scourge of television’s improprieties. The video was rated overtly misogynist as well as unnecessarily violent. Part of the coalition’s disdain was a reaction to Hooper directing the video in his characteristically apocalyptic vein. The central sequence of the three-minute Dancing with Myself fantasy features a group of ghoulish dancers surrounding Billy on top of a building and clawing the edge of a stage apron. Like a blond monster, he takes a jolt of electricity from two ducts and, galvanized by the force, blows the zombies off the roof; they then magically regenerate, scale the building once again, and end up dancing subserviently before him. The most controversial scene, though lasting only a few seconds, is of a woman in chains with a rope around her neck, struggling behind a transparent screen.

“They don’t seem to realize that the woman in bondage is Oktobriana,” Billy protests. Oktobriana, an image of feminine strength, has always been his symbol. “Oktobriana is so important to my thinking she appears on my stationery…. The idea of being tied up is related to all of us, to our own bondage. Anyway, lots of women in this society are kept down — and I’m saying it shouldn’t be that way. People think the video is too violent. But what it is too appealing. Not violently appealing, but appealing in general. Adults superimpose their own experiences over what they see as horrible. They’ve already been tied up so they’re genuinely afraid. And in the video it’s the idea that society is violent and the end of the world is happening and that violence is what holds people together. And what we say at the end is what it should be — dancing, music, and happiness. And above us, as we’re dancing, is the banner of Oktobriana.”

Billy is late for his interview at Trader Vic’s in Manhattan, held over by a personal appearance at Tower Records, where his presence attracted so many fans that whole squadrons of police were needed to contain the potentially riotous situation. Idol had been asked to remain at the store long enough to accommodate all those who had been waiting in subfreezing temperatures for signed albums. Nattily dressed, Bill Aucoin precedes Idol’s late arrival by a few moments, chatting softly of his client’s latest opportunities.

Suddenly Billy sweeps in, his near-sepulchral paleness enlivened for a change by a suntan, his aquiline nose burned — he has just spent a week relaxing in St. Thomas. Heedless of Trader Vic’s dress code, he wears a maroon haik that cloaks his shredded black angora sweater, coquettishly baring one shoulder. The outfit is as calculated and iconoclastic as Aucoin’s temperament and dress are decidedly conservative. The two men speak a few words to one another, with warmth and respect, the raw jerky explosiveness of Billy Idol complemented by the silken-mannered Aucoin. Indeed, one sees Billy Idol as Aucoin’s prodigal son returned, tamed in a perceptible way. Aucoin zips off, telling Billy he will be at home later; Billy is left with the option of ringing him up at any hour he chooses.

The contrast is equally striking between Idol and the wrinkled Polynesian waiters who refill drinks and with shaky hands serve him his strict vegetarian regime of steamed vegetables, regarding him with beneficent curiosity. He orders a white-coconut-and-rum cocktail, which arrives in an iced glass shaped like a curvaceous woman, as the subject of his attitude toward women (as well as sex) is raised.

“I don’t like people who demean sex,” Billy says heatedly, looking at the glass. “Once a woman interviewing me asked if I had had any sexual failures… and I said, ‘Look, basically, I don’t think there’s any failure — it’s all success. I think it’s only an element of degree how you get on with people.’ One night you can be actually brilliant and the next night shit with the same person…. Sex isn’t anything wonderful and magical, it’s not anything terrible and awful. It’s kind of in between. One night it’s great having a wank, one night it’s great screwing some bird, one night it’s great getting a blow job. What’s the big problem?”

As outspoken as he is about his sexuality, he still clings to his personal life, trying to ward off public scrutiny. He has been involved with Perri Lister for years. She is a former dancer with the group Hot Gossip, which performed weekly on the Kenny Everett Show in Great Britain. Although in America Billy is the celebrity, in England the couple have been featured in newspaper photographs with Billy referred to as “Perri Lister’s boyfriend.” It was Perri Lister who portrayed the bride in the White Wedding video.

In light of Billy’s choice to live in America, the couple has had to face long periods of separation, their lives divided by careers bound respectively to each country and by those several-week stretches when Billy is on the road. Only recently has Perri seen the possibility of acquiring steady work, which would allow her to live in America on a permanent basis. As for Billy, he has sought companionship on a nightly basis for much of the three years he’s spent in the United States.

“Look at those two birds,” he remarks, “they’ve been looking at me. Are they young?” Suddenly growing sheepish, he says, “I don’t know quite what to do tonight. I always feel like picking up some extra birds, for a laugh. That’s my trouble. Perri’s a great bird. She’s really sexual, she is. I like girls who are really fucking wild. Cool birds are always a little bit way out. I’m sure Penthouse readers will like to hear Billy Idol says cool birds are way out. Even I’d want to read that.”

Outside the Plaza, Billy waits for a cab among elegantly dressed men and women, suddenly made smaller by the hotel’s opulence. People begin to smirk and frown at his bristled hair, his swaddle of shreds and cloaks. He seems out of place. But he is oblivious to such scornful attention.

What used to be clothing to him has now become costume; what used to be attitude has now become affectation. And this is probably not the last the Plaza Hotel will see of Billy Idol, a performer who has cleverly managed to survive. Maybe a year from now he’ll want to dine at Lutece, which will require compromise: a sport coat. Perhaps the punk will slowly fall away, leaving just another fabricated rock star.

He chose the name “Billy Idol” after all, so we should probably not be all that surprised by the tales told here, let’s be honest. That said, Getty Images has some dandy frozen moments in time of both Billy and Perri (along with some of the entourage of the era). They›re expensive to license, but you can look for free. Free is good. … Maybe not quite as free as Billy Idol back in the day, but you get the point. You may, of course, consider Billy Idol today and draw your own conclusions — or your own life lessons.