“I remember what it was like to work nine-to-five in a factory. It makes me thankful, no matter how much I bitch about the music business, that I’m not doing that. I have tremendous empathy for people who look forward to Friday night.”

The Piano Man

At a small dinner party this past summer, Billy Joel and Paul McCartney met for the first time.

“I feel like a jerk saying this,” Joel told his boyhood hero, “but I just want you to know that if you guys hadn’t done what you did, I wouldn’t be what I am today. In fact, the Beatles probably saved my life.”

“That’s all right,” McCartney assured him. “I said the same thing to Phil Everly, and I felt like a jerk, too.”

Like the Beatles, Billy Joel’s music transcends pop-music barriers. His audiences cross over into all ages, races, classes. He seems to articulate and exalt the intense feelings and experiences that people have in common: joy, despair, guilt, and love. According to Billboard magazine, Joel has become the “most consistent and prolific male album artist of the last decade.”

Yes, it has been ten years since “Piano Man” brought him national attention, but to Joel rock stardom remains “an abstraction … a ball of gas.”

He was born William Joseph Martin Joel, in Hicksville, New York, on May 9, 1949. His father, an engineer for General Electric, left home when Joel was seven. His mother, Rosalind, worked a number of low-paying office jobs to support Billy and his older sister. Somehow she managed to pay for her son’s piano lessons. The classically trained pianist loved rock ‘n’ roll, though, and seeing the Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show” was an epiphany. Here were four average-looking, working-class kids like himself, who were playing their own instruments and writing their own music. If they could do it, so could he.

When his senior year of high school ended-sans diploma (good grades, poor attendance)-Joel continued playing in the bar bands he’d joined. With an established local “blue-eyed soul” group, the Hassles, he recorded two albums and learned to play Hammond organ before the group broke up in the late 1960s. He then formed a new group, Attila, with the Hassles’ drummer, Jon Small. It was an experiment that didn’t work. Over a year was spent writing and recording an album for Epic Records, but they disbanded after a handful of live dates.

It was in the early seventies that Joel saw his dream of recording his own music come true. In 1972, Cold Spring Harbor was released for Artie Ripp’s Family Productions. It was a collection of touchingly naive, promisingly well-crafted songs. It was also horribly produced, and was the beginning of Joel’s legal problems with Ripp and Family which continue to this day. Realizing he was in less than capable hands, but signed to an ironclad contract, Joel simply “disappeared,” moving to Los Angeles with the woman who would later become his wife, Elizabeth, and her son Sean. Joel played piano in white-collar bars under the name Billy Martin. It took Columbia Records to bring him out of his self-imposed 18- month exile and put him on the Top 40 with “Piano Man.” It was his first hit, but it also pegged him as a balladeer, a label that would haunt him as his work took other tracks.

Two years later, Streetlight Serenade followed. After a turn at producing himself on Turnstiles, Joel joined forces with producer Phil Ramone. That happy combination resulted in The Stranger (1977), which moved Joel into coliseum-size arenas and went on to sell six million copies. The equally successful 52nd Street was next, a collection of jazz-influenced urban rock. Glass Houses, released in 1980, gave Joel his third platinum album and served to further confuse rock critics, who were having trouble pinning him down.

Critics be damned, the people seemed to love Joel. Yet as his star continued to rise, his personal life was falling apart. After a separation and several attempts at reconciliation, Joel and Elizabeth divorced. Ironically, that painful episode coincided with his most critical breakthrough, The Nylon Curtain. It was a powerful album, described by Joel as containing “four songs about, respectively, unemployment. guilt. pressure, and war the four horsemen of the apocalyptic American landscape.”

After his Nylon Curtain tour ended, Joel took a vacation in the Caribbean, where his life turned another corner. One night while at the piano in the hotel, a beautiful woman sat down beside him. Her name was Christie Brinkley and their courtship inspired Joel’s next big commercial and critical hit album, An Innocent Man.

Brinkley and Joel married last March and are awaiting the imminent arrival of their firstborn. At press time, they were still “playing the name game.” What of reports that the name “Ray Charles” was first on the list? Says Billy: “I don’t think she is going to go for that.”

This past summer, Billy Joel’s Greatests Hits Volumes I and II was released and two new songs, “You’re Only Human (Second Wind)” and “The Night Is Still Young,” were included. It quickly became Joel’s seventh consecutive Top 10 album.

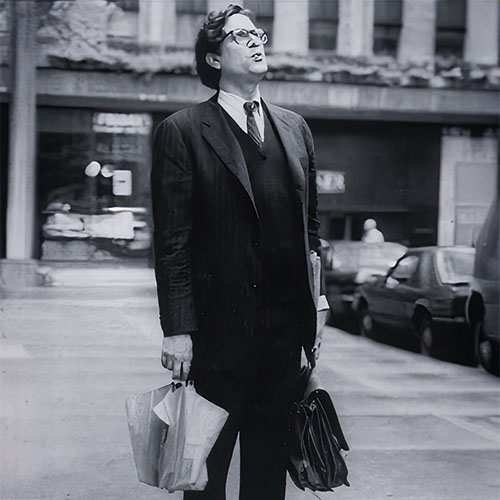

Freelance journalist Dennis Freeland interviewed Joel at the Hit Factory recording studio in Manhattan, where he was putting the finishing touches on “You’re Only Human.” Freeland reports:

“I first interviewed Joel in 1975. Ten years later the only changes I could detect were that his hair was shorter, he was tan, and seemed a lot more relaxed, although he chain-smoked Marlboros throughout. It’s well-known that Joel dislikes interviews, and he was wary and distracted at first. Then his guard dropped and he became quite open. He’s self-effacing, wry, and very aware of the relationship between information and entertainment. He’s hypercritical of people, including himself, but he’s also very sensitive to criticism, especially that of a personal nature. So I wasn’t surprised when his last words to me were: ’I just don’t want a hatchet job on me this time.’”

Let’s start with the question everyone wants an answer to. What made you fall in love with Christie Brinkley?

Not because she’s the most beautiful woman in the world. If anything, I was trying not to fall in love at that point. We found each other without really meaning to.

At the time, I was living in a penthouse at the St. Moritz, dating models, really getting around. Women I never dreamed would be interested in me were pursuing me. And there were a lot of revolving doors. But Christie and I started out as friends, and the romantic attraction grew out of that. It just happened.

Both of you tried really hard to keep the wedding ceremony and reception as private as possible. What was your reaction to the press coverage of the wedding?

We stayed in the city that night and got up the next day to fly down to the Caribbean, so I missed most of it. I was a little peeved with the New York Post, because they snuck in a photographer. Then People magazine started calling everyone we knew, trying to get an interview. Somebody from Christie’s office called them and told them we weren’t going to give them a story. And they said they’d run a cover story anyway. So we decided we might as well have input into it. It was sort of like blackmail.

Now that your personal life is on an even keel and you’re waiting for your baby to be born, do you have a sense that your music will change? Perhaps because you aren’t suffering as much?

No, because there are still things in my work that aren’t always going to be goodness and charm Life is always going to throw enough rocks your way. Just because I’m happy now doesn’t mean I’m going to write about baking bread. But I do think it would be a good thing to have a certain number of songs reflect family situations. I don’t think it’s unhip, and a lot of people who grew up on rock ’n’ roll have families now. But it would definitely have to mean something; I wouldn’t put out a song that was just an empty exercise. Having a family will bring out new feelings, but I don’t know what they’ll be until I start to have them. That’s the story of my life. I do things on impulse, which is why I called my publishing company Impulsive Music. I’m not Machiavellian. I don’t really plan things out. Contrary to what “I’m supposed to be.”

You are a musician who has taken a lot of criticism from the press, and from music critics in particular. You’ve been called “facile” and “a panderer to public trends.” Any comments?

I thought out the “facile” comment once. What was wrong with “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens? It’s a great, lasting work. May not be as “heavy” as A Tale of Two Cities, but I would rather be remembered for “A Christmas Carol.” It reads like a charm.

Once you’re “big,” you’re considered establishment. Everything you do after that is suspect: “He’s had a taste of money, now the only thing that matters to him is making big bucks.” I keep reading that I’m this “Tin Pan Alley tunesmith who grinds out mindless pap.” That’s funny because that is the antithesis of what I do. I do it because I like it.

Do you think that the impressions you did onstage contributed to the critics’ refusal to take you seriously?

In the early days it was a necessity. I was opening for these rock bands, and when you’ve got 20,000 people yelling “Boogieee!” and you’re out there doing “Piano Man,” you better shift gears pretty quick. It was a shtick, no way around that. So there was a point where my substance was in question. I got pigeonholed right away, and that first impression lasts a long time. For example, a lot of critics didn’t like Glass Houses, and they said, “He can’t do a rock album he’s a balladeer!” I don’t have any preconceptions about myself. Each time I go in to record, I’m a brand-new kid again. I’m surprised when I get bad reviews-I put an album out because I think it’s good. I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t believe in its quality.

You’ve given up ripping up reviews onstage?

Yeah, that was not a wise move. You can’t criticize the press. You know, I have no problem with somebody not liking my music, but I do have problems with lies being told, and I have problems with insults, and I have problems with people questioning my motives and my integrity. I’ll always be pissed off about that.

Are there certain rock writers that you listen to?

There are. To be honest, I usually agree with most of them, when they are writing about other artists. I pick up a New York Times and I read Robert Palmer, who I know hates my guts, and I happen to agree with a lot of his opinions about others. Tim White has always been fair. I don’t even have anything personal against Dave Marsh, who has been one of my biggest detractors. I just think in my case he’s wrong. But this troubles me, because you start to wonder, Are they right about me, if I agree with them on other reviews? So these things haunt me.

In an interview, Paul Simon said he loved your music but wished it was more oblique.

I can’t be what other people wish me to be. Sure, I’ll take their criticism under advisement. Paul is brilliant. He has a great command of the language. As a wedding present he gave me the entire Oxford English Dictionary, which would take up this whole room. I said, “Are you trying to tell me something?” He said, “Yes.”

Hall and Oates take a lot of critical flak, but Daryl Hall made an excellent point when he said, “We’re in popular music. If you’re not popular, you’re irrelevant.”

How did the Billy Joel look come about?

I was searching for something distinctive to wear onstage. It was the time of sequins-and-glitter rock, and then there was the other side, the Grateful Dead Tshirt-you-haven’t-washed-in-five-weeks with-”Right-On”-painted-on-it school of dress.

I wanted to make a statement. I was trying to say that I respect the audience. I thought maybe I’ll wear a suit, but I looked like a businessman. So I put on jeans and sneakers-I love sneakers but kept the tie. I never meant to get locked into it. The band made fun of me a lot. “What’re you wearin’ a tie for? You’re in this business so you don’t have to wear a tie.”

Your latest hit single, “You’re Only Human,” was written especially for the Greatest Hits album. Can you talk about why this particular song means so much to you?

I wanted to write a song that said, “It’s okay to make mistakes, it’s okay to be human. You learn from your mistakes-they’re the only thing you can really call your own.” And I wouldn’t be saying this in the song if I hadn’t had a suicidal experience.

This was the time you swallowed Lemon Pledge?

No, that was the second time. The first time, I took a whole bunch of pills. I was around 21, I’d broken up with a woman, nothing was happening for me as a musician, all my friends were at school or over in Vietnam getting killed. I just thought, Who needs another failed musician? I know how it feels to be so low that you don’t think you can come out the other side, and I wanted to use that feeling to help others.

Were you hospitalized?

I woke up in the hospital and had my stomach pumped. They released me because they thought I was just another kid trying to get high. But that wasn’t it at all-I’ve never been a pill person.

There’s been a lot of publicity about kids offing themselves at a horrifying rate. Everyone gets a second wind around 25 or 26, when you realize that everyone fucks up. The song doesn’t dwell on suicide. It sort of implies that this guy has a problem, he’s down on himself. And I wanted to say it’s okay to make mistakes.

Are you able to work on assignment, like offers to do movie soundtracks?

Well, it has to be my deadline, my idea. I get screenplays all the time, good ones, but they are outlines: “This is where Mary walks home at night; this is where Mary’s song will go.” I can’t write like that. I could see a scenario written around my music-that could happen.

Yet you did write “Easy Money “ for the movie.

I did that more from Rodney Dangerfield’s persona than from the specific screenplay. When I think of Rodney, I think of rhythm and blues. He asked me personally if I’d do it and it seemed like a fun thing to do. Actually, the song did kick off what the style of the album would be, though I didn’t realize it at the time.

There were published reports that you were signed to a movie deal that involved acting.

I saw that, too-a buncha baloney! We got offers from movie companies for me to do soundtracks. But I’m not an actor. I have to do work in videos and I hate it.

You hate making videos?

I just don’t enjoy the process at all, even though I know videos are becoming so important. As a new artist, you can’t break through without them. But I think it’s going to drive out a lot of established artists. What’s also a shame about it is that kids are not going to be able to hear music without having a visual image attached to it.

When I write a song, I feel I’ve created an atmosphere, painted a picture. When I get down to that final mix, and the record is mastered, it’s complete. I feel I’m defacing my own art to have to do a video on top of that. I strongly resent that.

As a matter of fact, I happen to think that television might end up killing rock ’n’ roll. Every channel has a video show and they’re all infatuated with rock, as if they just discovered it. Television is going to end up sanitizing rock ’n’ roll, making it like “Hollywood Squares.” I don’t trust television getting involved with rock-I never have and never will. To me, rock ’n’ roll is something that your mom yells at you to turn down.

Do you have problems with fans who like you too much and may even want to physically harm you?

There’s a certain type of person whose life has a void that only a hero can fill for them. I can relate to it. I’m not paranoid, I’m just careful. I’m more concerned for Christie than I am for myself. Our relationship has made me more cautious. For the most part, though, fans are harmless. They usually just want to have a piece of your time. I relate it to these professional autograph people, who just stand outside studios where they’re filming a soap opera. And they stand there all the time. They get an autograph from anyone they think may be famous. There’s a zombie like quality about them that I can’t relate to. It’s not pleasant. It’s not scary really, either. There are a lot of aspects to celebrity that I don’t really enjoy.

For example?

I’m a private person and I’ve experienced a loss of privacy. It’s not that I dislike people, but I want my own time. Say you’re in a restaurant and you don’t want to be interrupted. You can’t handle the situation like a normal person who’s been interrupted while eating. Because if you don’t handle the situation judiciously and you lose your cool, then you’re thought of as a snob.

And the other thing is that anything you do gets photographed and you’re considered part of this glamorous jet set. I saw pictures of Christie and me in the papers all the time, and even if we were only going to the movies it looked as though we were posing for these society columns. I’m not a jet-set person. I’m very sedate, with a big provincial streak.

Your songs obviously are very personal and have great meaning to you. Let’s throw out titles of some quintessential Joel songs and see how they evolved.

Joel: Great. Shoot.

“Goodnight Saigon.”

I wrote part of that around the same time as Cold Spring Harbor. I’d wanted to write a song about soldiers. I was urged by a lot of my friends who’d been to Vietnam to write a song about it. I said, “Hey, I’m gonna get killed by the critics. I wasn’t there. Who the hell am I to write this song?” Pretty much all the images that are in there are from my friends. The impetus to write the song started when I read the book A Rumor of War, by Philip Caputo. The guy in the story went in to fight all gung ho and became very disillusioned. And that’s what I wanted to write about – the soldier’s experiences, and hopefully, cumulatively, it would be an indictment of war in general. Dave Marsh said it “bordered on obscenity” because it “didn’t take a stand,” and he called it “a wrongheaded song.” I don’t feel I have to apologize for that song.

Then how do you feel about the Stallone movie Rambo and the Rambomania that’s followed its success?

What Dave Marsh said about “Goodnight Saigon” is what I felt about Rambo. I thought it was the worst piece of garbage I’d ever seen. The action scenes are very entertaining, but something scary happens to the audience. While Christie and I were sitting there, these guys sitting around us were yelling, “Kill, Rambo, kill,” every time he’d blow some people away. The reaction of the audience really disturbed me. And I think a lot of the feelings had to do with the timing, because we saw it just after the last hostage crisis.

How did your Vietnam vet friends feel about it?

They didn’t like it. They don’t like Stallone passing himself off as a representative of the Vietnam vet, especially since he was home making porn movies at the time. Now I don’t have anything against Stallone personally, but I found the movie very objectionable. That’s what upset me about the review of Greatest Hits in Rolling Stone-when they compared “Goodnight Saigon” to Rambo. Because that movie is against everything that I stand for.

“Christie Lee” is about your wife?

“Lee” is Christie’s middle name, but it’s not about her. I liked the sound of the name-it’s a great rock ’n’ roll name. Like “Stagger Lee.” I didn’t intend to use it on the album. It was just an exercise-fun to play. The band liked it, so we put it on the record.

“Everybody Has a Dream.”

That predates Cold Spring Harbor. I conceived it as a James Taylor-type song. It sounded sort of flat when I tried it out in the studio, so I decided not to use it. Then when we were doing the Stranger album, I wanted something with a Gospel feel, so I picked it up again. I always believed in that song.

“Room of Our Own.”

It was time for a banger. We wanted something with light sarcasm, but with dark references in it. It’s not specifically about me. It could partially be about my first marriage. I was saying, “It’s okay to have a room of your own-to be apart, to be separate.” It’s critical of the other person in the relationship, but the guy is also poking fun at himself, too.

With “Big Shot,” a lot of people thought you were being preachy.

People don’t realize that I don’t really take myself that seriously. My music, yes; myself, no. It’s a hangover song. I remember looking at myself in the mirror one morning, hung over, and saying to myself: “You had to be a big shot.”

The verse about the Halston dress was perceived as yet another put-down to women. Actually, “Halston dress” just sings great. That’s why I used it.

“Stiletto.”

That was a song about a bitch. It was called a misogynist song, but I actually knew a woman like that. I don’t care if it’s popular or not. The image of a woman wielding a knife just seemed more malevolent than a man. I know the knife has been perceived as castrating. Some people must’ve missed the point of that song. It’s not the woman who’s weird, it’s the guy in the song. He was a masochist.

“Rosalinda’s Eyes.”

That was a love letter that I think my father should’ve written to my mother. When I sang it, the title just had a nice feel to it. My mother’s name is Rosalind. From what I gather, my father wasn’t particularly romantic to my mother, so I made up a whole scenario.

Your mother must have been very moved.

No, I don’t think she got it She said, “That’s a nice song.”

“She’s Right on Time.”

I think it’s a really good song. The video ruined it. But the song – good chord construction, good vocal, good harmonies.

“Weekend Song.”

To this day I remember what it was like to work nine-to-five in a factory. It makes me thankful, no matter how much I bitch about the music business, that I’m not doing that. I have tremendous empathy for people who look forward to Friday night. I still get a little crazy on Friday night. I don’t think the song was that good. I tried.

“Until the Night.”

I was trying to do a song that would recreate the same feeling I had the first time I heard “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.” I even sang a duet with myself at the end-with the high and low voices. A production num-bah. Textural song.

“My Life.”

I don’t think it’s a very good song. It hasn’t held up. It sounds a little wimpy to me now. We do it stronger in concert.

“Mexican Connection.”

We still play the tape before live shows. It became a signature thing, and it creates an atmosphere. It’s pleasant to listen to-an exercise in movie-music writing. Theme music from an imaginary western.

“C’etait Toi.”

Argh. Big mistake. I never should’ve let that go. I like the chord structure. The lyric is the biggest hunk of shit I ever wrote. [Speaking in sticky-sweet tones] “Here I am. in this smokey place, with my brandy eyes.” I want to puke when I hear that. I had a guy from the Alliance Francais teach me the lyrics in French. I sang it in France and I’ll never forget the audience going, “What zee hell is he talking about?” One of my few regrets.

“All for Leyna.”

I wanted to relive the angst of being 15, 16 when you go through all kinds of hell because of breaking up with a girl. I used Germanic, Wagnerian chords straight eights-this frantic minor key of the anguished teenaged love.

“You’re My Home.”

Oh, yes-from my Gordon Lightfoot period. I was trying to play the banjo with my piano. “Summer, Highland Falls” and “Travelin’ Prayer” are both like that. An attempt to write a folk song on a piano-which is very difficult. I wanted to write a wine-and-roses song. It was Valentine’s Day and I wanted to write [laughs] a Hallmark card’ That’s how it strikes me now. I get critical of the earlier, cornier stuff. At the time, I meant it.

Is “Vienna” about your father?

Yeah, I went to visit my father there and saw a lot of elderly people working. They weren’t put out on a porch to rock their old age away. What Vienna meant to me was a productive old age. There’s a reason to be old. You don’t have to do everything while you’re young. Having a goal is fine, as long as you know that personal happiness is something you have to pursue your whole life.

Do you write many songs on guitar?

No. Although some songs on Glass Houses were written on electric guitar. The words to songs on Nylon Curtain were written on guitar. But I haven’t done that with any of my recent work.

You’re self-taught?

Yes. I’m self-inflicted on guitar. I’m not very good. I can pound out a rhythm a little bit. Actually, now I’m using different keyboards.

You caught a lot of flak for “It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me.”

Musically and lyrically I think it’s a really good song. There was a lot of controversy about it. Critics said I was poking fun at New Wave. … I love New Wave. I thought it gave the whole music business an enema, which it needed at that point. What the song was saying was “Wait a minute, this is not necessarily that new.” It reminded me of early sixties music: the simple chord patterns, the pounding beat, the sparse arrangements. It was just saying, “Don’t be bamboozled by the critics telling you that this is all new.” New Wave is just kids taking music back into their own hands again. “Next phase, New Wave, anyway, it’s still rock and roll to me.”

“Tell Her About It.”

Remember those girl groups? They would always sing [singing], “Listen, girl.” Diana Ross did it, Martha and the Vandellas, the Dixie Cups, they all had songs with the older girl giving the younger sister advice. I wanted to turn it around and do a “Listen, boy” song. It is a lesson I learned. If you want to keep a relationship, you’ve got to communicate. I didn’t want to get preachy, I wanted the song to be fun. So I set it in a Motown motif. Hmm, that’s a good name for a group. I didn’t think it was going to be a single. I said, “Taken out of context of the album, that song could sound like Tony Orlando and Dawn.” That’s why I’m always afraid when they put out a single.

Do you ever find yourself in a situation where you’d love to make a song longer, but you just don’t have the room? It must be really hard to have to edit yourself in that way.

I love to go on and elaborate and just write more sections to a piece of music, but you know you’ve got to remember that it’s going to be on the radio and there is only X amount of time. It’s painful to edit. On the other hand, I do admire efficiency.

Some recent examples where you had to cut and paste?

On “You’re Only Human,” we had to cut the sax solo for the single. We refer to that as cutting off parts of the body. For that song we had to chop off some fingers… and a couple of toes. But, you know, you can still function with some fingers and toes missing. On the other hand, on the edit of “The Night Is Still Young,” there’s a quiet part where there isn’t a lyric, just synthesizer. It’s actually where the song takes a breath, and to me it’s very necessary, but practically speaking, it’s not essential to it when it’s on the radio. So that to me was like cutting the lungs out of the song. It was a matter of that or cutting out the heart or maybe slicing the balls off. So I went with the lungs. It’s functioning now… on a respirator.

Who do you think is “the Billy Joel fan”?

They’re all individual thinkers. I’ve never really tried to analyze it. I don’t perceive people who listen to my music as one big mass. To me, they are all individuals. That’s why I was against this newsletter, The Root Beer Rag, at first. I don’t like the word fan, I think it dehumanizes people. So I said, “Instead of making a fan magazine, why don’t we just put out an information sheet, without any of this ’Hey, did you get the new Billy Joel doll?’

Wasn’t there some merchandising in there for a while?

There is merchandising stuff in there, that’s true. I fought it for a while but I figured that a lot of people are selling Billy Joel T-shirts, made out of garbage material, and they’re charging a lot of money. People assume that I’m getting the money anyway, even though I have nothing to do with it. So I’d rather that they buy a good T-shirt. Frankly, I don’t press it. Merchandising is a whole new part of the business that I don’t understand.

If it’s any consolation, you are the artist that bootleggers are afraid of. Have you managed to stop anyone?

I don’t know. You can put out one fire and another fire starts up somewhere else. Look what they’re doing with the “U.S.A. for Africa” merchandise. They’re bootlegging that stuff. That’s obscene. They’ll rip anybody off. Then they cry how they’re getting hurt by the big guy. Give me a break. They’re ripping people off. They’re thieves.

There are three unauthorized Billy Joel biographies.

There’s three? I only know about two.

Have you considered authorizing the real Billy Joel story?

No. I don’t want the world to know all about my personal life. I mean, to really do a book right, you have to dig up all kinds of things. Basically, I don’t feel I’ve lived long enough to have a book written about me. If you’re going to write a book about somebody, shouldn’t they have lived an entire life first? So that there’s a beginning and an end? This is a phase of life I’m in, it’s not a complete life. I have no intention of dying, although I’m sure some people think it would be a good career move.

Do you still consider Nylon Curtain your best work, or your favorite work?

I’m particularly proud of that album, but, on reflection, it may not be my best work. I think An Innocent Man was really good, but it came about so easily. I really didn’t sweat over it, the way I did with Nylon Curtain. Even though it was the most critically acclaimed work I’ve done, I think Glass Houses was just as good. I change my mind from week to week. You know, I still think the best work is yet to come.