Hewed from limestone some 30,000 years before Christ, the little ochre-stained statuette called the Venus of Willendorf is our most ancient female image.

Titillation

Since her discovery in 1908 in a prehistoric hunting camp in lower Austria, learned men of all nations and hat sizes have argued the precise mystical nature of the chubby goddess. One aspect, however, is agreed upon by all: she’s got big ones.

Since her discovery in 1908 in a prehistoric hunting camp in lower Austria, learned men of all nations and hat sizes have argued the precise mystical nature of the chubby goddess. One aspect, however, is agreed upon by all: she’s got big ones.

Since the dawn of his creation, man has worshiped the soft protuberances of the female thorax. This is rightly so, for the bounties of the breast are wondrous and many. In tender infancy the breast gives man the very sustenance of life, and in the hale manhood that is the fruit of that sustenance, the breast gives him something to diddle with during commercials.

Although mastomythology is a relatively new field (in fact, it came into being just this very moment), its study is rewarding and fruitful, and while it will by no means unlock for us the secrets of the universe, it will lead us to a better and truer understanding of at least those parts of the universe that are usually found tucked away inside brassieres. This knowledge, like all other knowledge, has not come cheaply. But, unlike the gentleman on TV from the data-processing school, I offer it for free, asking you to send no money, but only to remember who your friends are.

Man has mixed religion with many unlikely things — war, money, Pat Boone, and such — but rarely has his imagination been so fired as when he mixed his religion with titties. At Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, early Greeks worshiped the pre-Olympian goddess Artemis. The statue they devoutly adored, now known as the Diana of Ephesus, was the image of a beautiful woman, normal in all respects save one — she had more tits than a Guernsey cow.

To the south, in the central shrine at Knossos, stood an icon no less strange, no less revered, but certainly more menacing, than the Diana of Ephesus: the Minoan snake goddess. Her full dress covered all her body but for her gorgeous breasts, and in her outstretched hands were two writhing vipers. (The snake-tit effect has proved no less striking in our own time, as Theda Bara showed in Cleopatra. I am sure that psychiatrists have much to say on this point. I, however, do not.)

It was the Romans who devised the notion that our world and all its stars were the effusion of a tittie. The story had it that one night while Juno was nursing Hercules, her divine boob snapped out of his mouth, spraying milk into the heavens, thus creating our galaxy, the Milky Way. (The big-squirt theory.)

Tit worship was by no means restricted to the pagan world. The cult of Maria Lactans, one of the most pervasive cults in the history of Christianity, venerated the breast and milk of the Virgin Mary. Lucky among men, taught the Church, was the twelfth-century St. Bernard of Clairvaux. Reciting his prayers one day before a statue of the Virgin in the church of St. Vories at Chatillon-sur-Seine, Bernie was miraculously greeted by — shazam! — the Virgin herself. who, pressing her breast, let three drops of her precious milk fall onto his lips. (And, boy, were the other monks jealous!) This scene was later depicted by Filippo Lippi in The Vision of St. Bernard.

The cult of Maria Lactans got so far out-of-hand that by the time of the Renaissance, churches throughout Christendom boasted of possessing sacred vials of Mary’s milk. In his Treatise on Relics, Calvin complained that “there is no town so small … that it does not display some of the Virgin’s milk. There is so much that if the holy Virgin had been a cow … she would have been hard put to yield such a great quantity.” Although the Maria Lactans cult was eventually squelched, in the late sixteenth century, by lobbyists for the Immaculate Conception, one still encounters phials of the stuff in Italy.

Where there is worship, there also is fear. Women, real and imagined, have wielded their tits fearsomely since time immemorial. In the Iliad Hecuba bares her breast to her son Hector in an attempt to dissuade him from fighting Achilles. Phryne, the fourth-century B.C. Greek courtesan who modeled for many sculpted images of Aphrodite, persuaded a jury to acquit her of impiety charges by dramatically exposing her bosom in court. The Norse Sagas tell us that when the Norsemen were on the verge of being vanquished by the American aborigines in Vinland, Freydis, the bastard daughter of Eric the Red, saved the day by ripping open her blouse and slapping her breasts with a sword, thus scaring off the natives. Lola Montez, the infamous nineteenth-century actress, won the undying favors of Ludwig I of Bavaria by baring her boobs to him during a formal audience. But the greatest depiction of tit power is Giotto’s personification of Anger on a wall of the

Scrovegni Chapel in Padua: a woman rending her bodice to reveal herself in vague and utter defiance of all.

Freud, who comes in handy at times such as this, believed that all men fear the breast, and that their fear is rooted in infancy. “Not without surprise,” he wrote, “do we hear the accusation: Mother has not given the child enough milk, she hasn’t suckled it long enough …. So great is the voracity of the infantile libido! The aggressive oral and sadistic wishes are then encountered in the form which early repression forces on them: namely, the fear of being killed by the mother.” (And if you buy that one, I’ve got some coastal real estate you might be interested in.)

But what of the simple, natural beauty of the breast? To capture the essence of that beauty, we should perhaps turn to our poets, that noble race which, lacking the skills of any useful trade, teaches us lesser beings to read the subtle soundings of our senses. While literature certainly has employed some rather unique similes in describing breasts — “like two young roes,” offers the Song of Solomon; “like flapping sails,” says Meleager of Gadara; “like bouquets of hyacinth,” muses Federico Garcia Lorca — most poets fall into one of two groups when they are confronted with the breast. The first and more popular of these groups comprises the Dessert-Menu School of tit poesy. Our oldest surviving example of boobie verse, found on a scrap of Egyptian papyrus dating to around 1300 B.C., is of this type, describing milady’s breasts as “love-apples.” The classical poet Rufinus referred to “the golden apples of her breast.” Paulus Silentiarius, writing in the sixth century, used the phrase “two apples” in several poems, before finally falling overboard with “to clasp in my hands your apples nodding with the weight of their clusters.” By the sixteenth century, apples alone would no longer suffice for the menu. “Her brest like a bowie of creame uncrudded,” dreamed Edmund Spenser. The award must, however, go to that horny cleric Robert Herrick, whose seventeenth-century poem “Upon the Nipples of Julia’s Breast” manages to work in not only cream and two fruits but also a floral setting for the table:

Have you beheld (with much delight)

A red-Rose peeping through a white? Or else a Cherrie (double-grac’t)

Within a Lillie? Center plac’t?

Or ever mark’t the pretty beam,

A Strawberry shewes halfe

drown’d in Creame?

Or seen rich Rubies blushing through

A pure smooth Pearle, and Orient too? So like to this, nay all the rest,

Is each neate Niplet of her breast.

Secondly, there is the Surf-’n’-Ski School, the prototype of which is found in the Homeric “Hymn to Aphrodite” and its phrase “her snow-white breasts.” Rufinus, taking time out from his apple-picking, gave us “her breasts like the spring-tide.” And in the ninth-century Arabian Nights, we encounter breasts that are a combination of both: “Your breasts are snow; I breathe them like sea-foam.” In The Rape of Lucrece, Big Bill Shakespeare offered “Her breasts, like ivory globes circled with blue, a pair of maiden worlds unconquered.” Nice, Bill.

Writers of prose have seemed to be more concerned with the size of breasts. This had been especially true in the modern era. Emile Zola, in Germinal, told of a widow “with a pair of breasts each one of which required a man to embrace it.” For this sort of thing, however, I much prefer the fine beatnik novelists of several years ago. In the much-ignored Jazzman in Nudetown, Bob Tralins labors over “those huge mountainous breasts.” Not to be outdone, Richard E. Geis, in his Like Crazy, Man (“Adult Reading”), says, “Her large breasts swayed and moved like huge hanging melons,” and, several pages later, “Gosh! Her breasts were out of this world. They were cantaloupes, self-supporting and silky-smooth, big and round and full.”

Many women that I have encountered share much with these notable beatnik authors regarding their concern for breast size. I cannot recall knowing many women who have not, at one time or another, confronted me with the question, “Do you like my breasts?” What, I wonder, do such women suppose one might answer? “No”?

The discomfort, folly, and expense that some women have put themselves through in their quest for mammary splendor is truly astounding, from the stiff, long-waisted corsets of the 1600s to the wire-reinforced brassieres of today. (The modern, cupped uplift bra as we now know it was devised by a Russian-born retailer named Ida Rosenthal. She called her brassiere Maidenform, as in “I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night in my …” The alphabetical cup sizes came along later, a 1935 Warner’s invention.) Patented falsies hit the market in the mid-nineteenth century and immediately became a boom business. By the turn of the present century, fortunes were being made selling “bust creams,” ointments that promised to increase the size of milady’s bosom. These wonder drugs are still advertised in various Hollywood fan magazines and tabloids.

Yet, in spite of all this, the message has always basically been, to quote an old Coasters song, “You can look, but you’d better not touch.” A further irony is that those women who seem to regard their breasts as the center of their being are often offended (whether sincerely or affectedly, I leave to Messrs. Freud and Geis) when someone deigns to agree with them. I personally have known certain women to take exception to the most casual and innocent comments of this nature, such as, “I judge all broads by the size of their tits.” (Many women, like many men, would rather be judged by the quality of their minds than by the simpler and more efficient standards of breast, penis, or hat size. It is, perhaps, best to humor such people.

But, ah, yes, tits. My mind goes back to the wild and wanton salad days of my youth, before I decided to settle down to a life of faithful tranquillity with my right hand (don’t worry, I say the same thing every year along about this time), back to the days when a tit was a tit.

First there was La Margaret, the flame of my adolescence, with whom I explored the miracle of love, or at least that part of the miracle reserved for unrequited hard-ons. I wanted her more than I had ever wanted anyone, except perhaps for Irish McCalla, who played “Sheena, Queen of the Jungle.” We were fourteen, both of us, and had never been laid. “I’m too young to be an unwed mother,” she kept telling me. I’d try to creep my hand upwards beneath her skirt, but whenever I reached her garters, she would yank my hand away, complaining, “Whadaya messin’ with my apparatus again, Nicky?” So I concentrated on her breast. I wanted that tittie. It had nothing to do with spring-tide or golden apples — I just wanted that tittie. But she wouldn’t let me have it. More than a year passed before the day of jubilee arrived. I remember it clearly. We were sitting in a Times Square movie theater watching, or at least looking at, Invasion of the Animal People. (I am convinced that, in the course of my search to get laid, I saw every film that was made between 1962 and 1965.) Halfway through the movie, I had a fine idea. With my arm draped over La Margaret’s shoulder, I pretended to fall asleep. After a few minutes, I threw in a couple of fake little snores. Before long, she did as I had expected: slowly tugged my hand down from her shoulder to her breast, as I grinned the grin of the wise and listened to the rest of Invasion of the Animal People with my eyes closed.

Most of my experiences among breasts have been quite pleasurable. But I do recall one rather traumatic occurrence when I was twenty years old. It was a Friday night, and I was sitting alone in Louie’s Bar on Bleecker Street in New York, drinking beer and figuring out how to spend my first hundred. The largest, most prodigious woman that God had ever made — no, God could never have made her; she must have escaped from a forbidden Babylonian creation epic — strode into the bar-room, ducking so as not to strike her head against the ceiling beams. Her high heels thundered with the slow cadence of an unfurling apocalypse. With terror I sensed her approaching me from behind. Then I felt her. Forget cantaloupes. Forget huge mountains. Forget Zola’s widow. These were all the primordial oceanic might that Einstein’s curved space could ever contain. They were pressing upon me, driving me downward into the horrible unknown. Then I heard her voice. She was whispering, but still it pained my ears, like low waves of infrasound:

“I wanna take ya between my breasts, baby,” she said.

Right then and there, my penis shrank two inches. Don’t laugh: I’ve never regained them.

Anyway, those are just a few of the tits in my life.

Yes, we have come a long way since the Venus of Willendorf. But what of the future of breasts? Within recent years they have diminished noticeably. Something happened there, on the way from Jayne Mansfield to Bo Derek, and I don’t think we can blame it on phosphates in the water. Buns, buns, buns — that’s all we hear these days! Whatever became of knockers, howitzers, torpedoes, Elsies? To paraphrase the Kingston Trio, where have all the titties gone?

Are breasts becoming vestigial organs? Will there be no more sprouting chicken fat among the girl-creatures of our once great land? Did Olive Oyl know something that we don’t? Will there be no more cantaloupes in Nudetown? Must Dolly Parton die to teach us our errors? Are designer-denim bras all that can save us? Was it all just a dream, or did it really happen?

These are questions that urgently need to be answered, preferably by someone, unlike myself, who knows what he’s talking about. As for my own part, I can only say that, though I care little about the future of humanity as a whole, I care a great deal about that of her breasts. Let whales and seals and soaring condors be damned; it is the great American tit that must be saved. While I may not agree with a person’s cup size, I shall defend to the death, or at least to the point of risking a bad cold, her right to hold her tits high; for that is the way it must be.

I’m doing my part. Can you say the same?

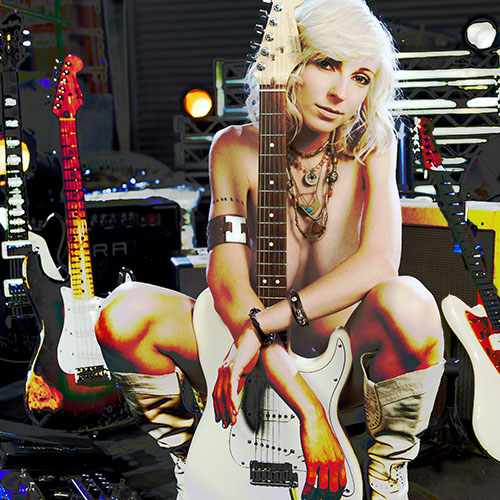

One can find many, many slang expressions for breats, and nearly as many ways to subtlely reference them. Full disclosure, we did find the title of this article among the most clever on that second point, even if slightly on the nose — or, y’know, about a foot south of the nose. If you want the science angle, you can start here, but if you need to do more visual research, you clearly need to Subscribe to the magazine, or, should you prefer your research to be bouncing around, join PenthouseGold. … Some shameless plugs just come easier than others in life. We’re taking the win.

OH! In case you were curious, we did in fact use the Pet of the Month from May, 1982, to serve as the header image for this historic update, she of the unusual name of Ute Hochmeister. Penthouse would be an excellent reference should one wish to prove that beauty endures across the decades, although “across the centuries” could be where things start to break down. Some forty years later as of this update, we still think Ute is way prettier than Venus of Willendorf.