The legend and lore of the American cowboy boot. “Rising by his own bootstraps.” “Boots and saddle.” “Boot hill.” “A man’s as good as his boots.”

Boots Scootin’ Trailblazers

The boot is an integral part of Western legend, part folk myth, part fashion, as American as violence and apple pie.

The Western boot has a lore of its own, a connoisseurship as finicky as that surrounding wine. In Texas and the Southwest there are master boot-makers whose work is collected like the violins of Stradivari, with regional differences of style and decoration that are still hotly debated. There are people who think nothing of spending $1,000 or more on a pair of boots, and others who collect pairs by the hundreds; but the most surprising thing about them is their ubiquity — anywhere you go in the United States you will see someone wearing Western boots.

It was not always so. When Lyndon B. Johnson came to the White House, the Western boot (Texans like to think of it as the “Texas boot,” but this is only partially true) was still regarded as a mark of regional provincialism, not much better than bib overalls or a Maine farmer’s cap with earflaps. Johnson owned boots, like most Texans, but he didn’t wear them in Washington. He put them on when he went home to campaign, as a sign that his heart (or, at any rate, his feet) was still back with the folks at home. Even in Texas, boots had a certain negative connotation — they were the hallmark of the Texan who hadn’t outgrown Texas, associated in the public mind with big talk and lack of sophistication, forever carrying with them the faint suggestion of cowpats and horse-dump, the whiff of the stockyards.

In the late 1930s and the early 1940s, the Western boot spread throughout the United States in the form of children’s cowboy outfits, inspired by the enormous appeal of Western heroes in the movies. The Lone Ranger, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, and Red Ryder all encouraged kids to dress up as cowboys (and, thanks to Dale Evans, cowgirls). There was hardly anyplace in the United States where you couldn’t see children in tiny high-heeled Western boots, a cardboard Stetson, and fancy fringed shirts, wearing plastic Colt six-shooters in miniature gun belts.

These outfits were inexpensive and the boots were basically toys for dressing up. As soon as they got old enough, kids moved on to penny loafers or basketball sneakers. Back then cowboy boots were not something grown-ups wore, outside the Southwest.

It was the sixties that turned the cowboy boot into a national phenomenon. Young people threw away dress codes, along with everything else, and found in the jeans and boots of the cowboy a style that symbolized the freedom of a simpler (if mythical) America, and which also had a certain androgynous potential. The casual look spread from the campus to the adult world, and the boot rapidly became a standard part of everyone’s wardrobe (to be replaced, to some extent, by running shoes a decade later).

“Thirty years a cowboy, and never stepped in horseshit yet.’’ – Old cowboy’s wisdom

The West, which has always held a fascination for Americans, became a national style at the exact moment when the West itself was in the process of vanishing — being engulfed by four-lane highways and neon strips, by “ranch homes” where there used to be ranches. It is ironic that cowboy clothes have become high fashion while the cowboy himself has ceased to exist in a world where cattle are now raised in feedlots and shipped by truck, and where the horses have become luxuries rather than working animals.

The cowboy preceded the boot with which he is so often identified. The genesis of the boot was in Spain, where the horseman established his superiority over the peasant on foot by wearing high boots with pointed toes and soles so thin that they were almost impossible to walk in.

Much has been written about the practical reasons for the shape of the Western boot — the high heel prevents the foot from slipping through the stirrup, the pointed toe makes it easier to locate the stirrup, the fancy stitching stiffens the most important reason for wearing classical Western boot was to the wearer as a horseman who need to walk. It was not just that boots were uncomfortable for walking — they were deliberately designed to show the horseman’s contempt for the whole idea of walking. The harder it was to walk in them, the better — which explains why the heels became higher and more slanted and the toes so sharp that the tips bent up like those of a court jester.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Horsemen have always been proud, and their clothing has always been dictated by the demands of a life in the saddle. Horse-men, like motorcyclists, need clothes that don’t flap in the wind (which frightens the horse) or snag on fences, bushes, and trees. Horsemen need pockets, with flaps to keep the rain out and buttons or snaps to keep the contents in. In short, almost everything we think of as “Western” has a practical value, from a horseman’s point of view, and was derived from Spain, via the conquistadors, who in turn inherited it from the Arab and Moorish horsemen who conquered Spain.

“It is ironic that cowboy boots have become high fashion, while the cowboy himself has ceased to exist.”

In the New World, the horsemen raised cattle as they had done in Spain, except on a much larger scale, for in many cases the size of their ranches exceeded that of the provinces in old Spain. They developed the work clothes that were to become known throughout the world as “American” — the wide-brimmed, high-crowned hats, the leather chaps to protect their legs from the cacti, the wide belts that gave support to the back and kidneys of a man who might be in the saddle 12 hours at a stretch. The “vaqueros” proclaimed their status as “caballeros” — horse-men — by wearing spurs with such large, sharp rowels that they were unable to walk without tripping over their own two feet, which didn’t matter to them, because they never walked.

When the Americans moved West in the mid-nineteenth century, they viewed these flamboyant antagonists with suspicion, even derision. They came from a culture in which the horse was used for plowing as well as for riding. They wore heavy boots that a man could plow a field or fell a tree in — and perhaps even ride in when he needed to — hats designed for a climate where the enemy element was rain, not sun, clothes that could be worn at church meetings as well as at work. They did not, to use a modern phrase, “go native” easily, or in a hurry.

The process of change was gradual, and probably inevitable — the climate and the nature of their work made it necessary to adapt in order to survive. Men shed their Jackets and rode in waistcoats. They gave up stiff collars in favor of bandannas to protect their throats from the dust. After the Mexican-American war, they cut the flaps off their army holsters to make them low-slung and open. To create the eminently practical Western hat, the Mexican sombrero was slightly tapered, keeping the wide brim that could be pulled down to protect the wearer’s eyes from the sun’s glare. They gave in to the vaqueros’ custom of decorating their belts and tack with silver conchos, which was borrowed from the Southwestern Indians. Above all, the gringos adapted the vaqueros boot and made it their own.

At first, men simply cut the tops off their own cavalry boots. which at that time came up over the thigh to protect the trooper’s legs from saber slashes — not the kind of thing you’d want to wear all day while on horseback under the sun. Even with the tops cut off, the boots were too heavy to be comfortable, designed as they were for protection. The Spanish boot became Americanized. The vaqueros’ boot was high. The Americans wisely lowered the height of the boot to make it easier to get on and off. The vaqueros’ boot was plain, often made of rough-cut suede leather. The Americans who disliked the flamboyance of vaqueros’ clothing, chose to decorate the boot instead, though the fancy stitching was intended to stiffen it. For the sake of comfort, the Western boot was made out of thin, soft leather. unlike a cavalry boot or an English riding boot, so the rows of stitching gave the boot a stiffness it would not otherwise have had — without them, the tops would have been floppy and wrinkled.

The early boots were, of course, handmade — every small town had a boot-maker, and each boot-maker developed his own individual style. No doubt, the cowboys brought him their particular needs and problems, and adapted by the individual skill and vision of the boot-maker, from these there grew a whole tradition of boot-making, a cottage industry par excellence, which made it possible for the knowledgeable cowboy to guess where a man came from by his boots.

And to judge him. A lot could be told about a man just by the way he looked after his boots — a man who wouldn’t take care of his own boots was unlikely to take care of anything else. Besides, a cowboy’s boots were his most important possession — sometimes his only possession. A cowboy’s boots were virtually the only item on which he spent money. They were expected to last a lifetime, and cowboys laid out what was, for them, a fortune — which explains why they wanted to be buried in them.

To cater to their needs, saddle-makers, harness repairers, and even barbers became “custom boot-makers,” largely in the towns that marked the end of the cattle trails, where the cowboys got paid off. In Kansas (where the cattle arrived at the railheads to the Chicago slaughter-houses), the sharply slanted heel was born. In the west of Texas, the chisel-shaped toe was preferred. For those who could afford it, boots were embellished with stars, or initials — simple decorations compared with today’s.

The period in which cowboys and cowboy boots flourished was brief. It began after the Civil War and ended when the Homestead Act opened up the prairies to farming and the railways pushed farther south, ending the cattle drives. By 1900 it was gone, a nostalgic memory at best. Like the antebellum mansions of the old South, the cowboy might have been forgotten altogether, had it not been for the movies. The cowboy’s battered old hat became the gleaming white Stetson, his patched jeans became formfitting ’’Western pants,” his tattered shirt with button pockets, pearl studs, and raised stitching became an object of high fashion. And his boots, of course, became glittering works of the leather craftsman’s art; multicolored and silver-studded, they became a symbol of the West that never was.

Even in the West, where people knew better, Western clothing became the fashion. People whose grandparents would have never allowed a cowboy in their house (cowboys were seldom welcome indoors, since they stank of horses and cattle and shredded floorboards and carpets with their boots and jangling spurs) began to adopt the boot as an item of everyday wear, an identification with a past that had suddenly become glamorous.

The Western boot-makers, at the tail end of a dying trade, found themselves experiencing a sudden and unexpected prosperity. What had once been a small, localized “cottage industry,” about to go the way of harness-making, blacksmithing, and wagon-making, stumbled into the big time.

Inevitably, the boot changed. It became more flamboyant — after all, it was now an object of display, rather than a “working boot.’’ It became lower still — since fewer of those who wore them would be riding horses. The exaggerated high vamp and slanted high heel of the traditional cowboy boot, designed for an owner who would rather be dead than seen on foot, gave way to lower, broader “walking” heels. The boot was also made to fit the foot more loosely, for as orders poured in, boots were manufactured and sized on a production-line basis, whereas the boot-makers of old constructed each pair by hand, making them tight because cowboys figured it was worth a year or so of discomfort to break in something you’d be wearing for the rest of your life — in fact, many of the real old-timers stood in a horse trough to pull their new boots on, so that the wet leather shaped itself exactly to the foot! No more. Suddenly, Western boots could be bought nationwide at outfitters, though naturally the largest selection was in the Southwest.

Today, the local “handmade” still exists — in fact, Sharon Delano and David Rieff have devoted a whole book, Texas Boots, published by The Viking Press (to which I am greatly indebted for much information and folklore), to the continuing practitioners of the trade. Anybody who wants to see a pair of boots made by Charlie Dunn, the legendary dean of boot-makers, should consult Texas Boots, which includes such other wonders of boot-making as Pancho (“The Golden Needle”) Ramirez’s three-dimensional flowers, stitched and inlaid on the tops of custom boots, and the perfect working boots of J. E. Turnipseede (who has a one-year delivery time) — not to mention silver-pearlized lizard-skin boots; boa-skin boots; alligator boots by Henry Leopold, of Garland, Texas; and James Leddy’s boots, worked in incredibly exotic leathers.

“Cowboy boots were expected to last a lifetime, and cowboys laid out what was, for them, a fortune-which explains why they wanted to be buried in them.”

The range of choice is endless, but a certain knowledge is required, and perhaps if possible at least one visit to Texas because these are not the kind of people who normally send out catalogs. Buying a pair of these boots is a once-in-a-lifetime experience that might be worth-while if only because the boots last a lifetime. Twenty years ago I had a pair made for me by Paul Bond, in Arizona, and I still wear them several times a week (black calfskin uppers, with blue-and-white fancy stitching, my initials in white kidskin, black sharkskin counters), and so far they have aged a good deal better than I have. And I wear my boots! I ride, I handle horses in the mud, I have even worn them riding in the rodeo in Madison Square Garden and at a working ranch in Montana. A little saddle soap, a lick of black Kiwi, and they look like new.

If you don’t want to go to the trouble, you don’t have to! Economic pressure has turned many old boot-makers into large companies, but the best brands — Justin, Larry Mahan (owned by America’s No. 1 rodeo cowboy), Nocona, Lucchese, Rios, Tony Lama, and Dan Post, to name a few — haven’t lost their craftsmanship, taste, or flair for design in the process of becoming big business. You can buy a pretty damned good boot “ready-made” almost anywhere in the United States, particularly if you choose a name brand. And it’s easier to wear many of the ready-made boots for ordinary street use, rather than custom-made boots, which are still very oriented toward the needs and taste of a horseman.

The main thing to remember in buying boots is that they must fit. Unlike shoes, they won’t stretch much — the tough, high-arched soles keep them in shape — so don’t assume that they’ll break in comfortably as you use them. They have to be comfortable from scratch. If you’re going to give them hard use, avoid fancy leathers and inlaid patterns. Those are for dressing up. In the end, a good plain boot, with tasteful stitching, lasts longer and looks better.

One thing you must be sure of is that the boot is pegged. The soles of cheap boots are nailed. The soles of good boots are held with two rows of tiny wooden pegs, which you should be able to see on the bottom of the sole where it curves to form an arch. Wooden pegs expand and contract, so the boot doesn’t fall apart or lose its shape when wet. Because of the wooden pegs, even the fanciest cowboy boot can be worn in the pouring rain and in mud without falling apart, whereas an expensive pair of shoes can be ruined by one bad rainstorm.

If you can, buy your boots at a riding store or “Western outfitter,” where the clerks will know enough to answer your questions. Tell them that you’re going to wear the boots for riding, because horse-men are notoriously fussy customers. The problem with buying boots in most other stores is simply that people who sell shoes don’t know much about boots. Few of them know the difference, for example, between a “needle toe,” a “chisel toe,” “a square toe,” or an “underslung heel” and a ’’tapered heel’’ ( a recent Nocona catalog shown in Texas Boots lists 12 various toe shapes and six different heels), let alone the finer points of stitching the “medallion” (those rows of stitching over the instep, the number of which is a matter of dispute among connoisseurs), the shape of the scallop top, or the distinction between “pull straps,” which are sewn on the inside of the boot, and “mule ears,” on the outside.

The instep should be reinforced with a steel shank if the boot is going to last, and the more rows of stitching the better the boot. If the stitching seems carelessly done, uneven, or widely-spaced, reject the boot. It’s hard to judge leather, unless you’re an expert, but the stitching usually tells the story. After all, a custom boot-maker such as Pancho Ramirez didn’t acquire the nickname “The Golden Needle” for nothing.

Still, a good operator who knows and cares about what he’s doing can turn out a damned fine pair of boots in a factory. As for how much you should pay for them, the range is enormous. If you want to go down to Texas to order a pair of boots in crocodile, anteater, python, ostrich, kangaroo, or sharkskin, or if you have a yen to have your whimsy carried out in colored leather by a master craftsman, you can pay hundreds of dollars, even thousands — the sky is the limit.

On the other hand, if you don’t care to spend a fortune on footwear, you can buy a pretty good pair of ready-made boots for not much more than a good pair of shoes — and have a lot more fun with them!

Boots, as men have known since Roman times, do something for a man that shoes don’t. In boots, a man walks tall, for he inherits a whole gamut of proud traditions: the cavalryman, the cowboy, the conquistador. The cowboy boot, in particular, seems to possess a built — in ability to transform the urban schlepp into the urban cowboy. Perhaps it’s the heels — they were never designed for walking, after all-that make it necessary to walk with a straight posture. Unquestionably, the sharp toes have a certain weaponlike quality. There’s no doubt about it — boots are sexy, which possibly explains why women have taken to them as passionately as men!

The West began as a tough, hard place to scrape out a living raising cattle on dry soil, and it has ended as fashion. Maybe that’s the way it has always been. The black-leather jackets and chains of the Hell’s Angels, once the mark of the greasy biker outcast, are now in style. Levi’s tough trousers (made from serge de Nimes, which passed into American as “denim”) were originally made for the California miners of the gold rush — and are now tailored by designers like Calvin Klein and promoted by Brooke Shields. Even the jungle fatigues of the World War II soldier have reappeared as fashion, complete with cartridge belts and bandoliers.

We take from the past what worked, what was practical, and what has survived. Indeed, form follows function, as we are so often reminded. And what is perfected for function is without exception always elegant.

The Western boot has survived and is now considered stylish in part because its form was once dictated by function, tradition, the demands of a tough environment, and the even tougher men who managed to survive in it. The boot is as perfect an object as anything our culture has ever produced.

What else can we buy that links us to the romance of the old frontier and is one thing that we can still make better than the Japanese?

And besides — what the hell — they look good!

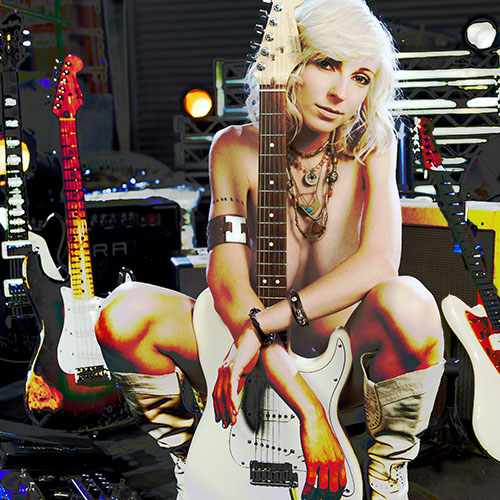

Naturally, we might be more interested in contemporary female cowboy boots, as one might expect. It would be nice if they had a voice like an angel while wearing them, but honestly if she has a “Save a horse. Ride a cowboy.” bumper sticker, we’re pretty much sold — even if they don’t have the song playing. … Of course we even found a museum, should you happen to be in the Oklahoma City area, but you can find that bumper sticker all over the place. We suggest starting by driving to some place with trees. Then find the local diner. … Hey, we all need to dream.