“I have to keep going. Like Richard Pryor, when he caught on fire, he ran down the street and kept running, and that kept him alive …. I feel I’ve reached the pinnacle of success. If it all just went away tomorrow, I’ve done it.”

Dan Aykroyd: The Penthouse Interview

It was the perfect partnership. John Belushi was a squat, overweight Albanian from Illinois with sinister eyebrows. Dan Aykroyd was a rangy but lumpy Canadian who was half English and half French. Together they became America’s best-known soul singers. Comics turned musicians — but never quite not comic — they dressed up like two old hipsters in black suits and stiletto ties, spoofed some old Sam and Dave bits, and christened themselves Jake and Elwood — the Blues Brothers. The act brought albums and tours and a film, at its peak generating $1 million a day. With its success, there was a deepening friendship. Aykroyd and Belushi bought adjoining homes on Martha’s Vineyard, helped each other with business deals, even created an interconnected pension plan. They also discussed, often and in detail, their funerals. In March, after Belushi died in Los Angeles, Aykroyd was there, as promised, for the send-off. He buried his friend in engineer’s boots and army pants, with three cigarettes and a $100 bill in his pocket. He also, for the burial, escorted the hearse in a style he knew Belushi would appreciate — outlaw black leathers and his bike.

His getup was criticized in some quarters. And in the months following Belushi’s death, and the scandal surrounding it, there were rumblings about Aykroyd as well. He had been unhinged by his friend’s death, they said in some quarters; he was engaged in bizarre behavior, trying to reach John on the phone.

Aykroyd, talking here publicly after keeping a long and wary distance from the press, denies that there is anything peculiar in his actions. But he does speak of Belushi in the tones a lover might use in speaking of a very special relationship, in romantic, even grand terms. “It was one of the great friendships of the decade, if not the century, and it will go down as such,” he says.

He can also joke. “What’s blue and sings alone?” he asks. “The answer is … Dan Aykroyd.”

The condition of loner is not, as it happens, unknown to him. Nor would he deny a certain independent and fun-loving outlaw streak — akin, in a way, to wearing leathers to follow a hearse.

Born in Ottawa thirty years ago, Dan Aykroyd was the eldest son of a high-ranking Canadian official who believed in both the work ethic and Mother Church. Aykroyd had trouble with both. He bounced from school to school and in his teens was expelled from seminary. (” Late-night vandalism, skipping mass, fucking off,” he once explained to Rolling Stone. “The Fat Mouth in Primary School … lots of corporal punishment as a kid … deserved.”)

He studied criminology in college. He had a happy life in Canada running an after-hours place, Club 505, which, he still claims, was “the best bootleg joint in Canada.” He broke into comedy at Toronto’s Second City and, at the invitation of Lorne Michaels, whom he had met at his club, joined “Saturday Night Live” in the days when it was the brightest show on television.

At “S.N.L.,” in the midst of more flamboyant and easily typed actors such as Chevy Chase, Gilda Radner, and John Belushi, he was the utility player. A writer as well as a performer, he had a cast of characters, many with a trace of menace under their nearly normal looks: he was a panicky, stuttering Tom Snyder; a paranoid, duplicitous Dick Nixon. He was a Conehead. He was, with Steve Martin, a “wild and crazy guy.” But it was with Belushi, even before the creation of the Blues Brothers, that a special friendship began. It may have been because the two could be so very different: Aykroyd often gentle and deferential, Belushi eager to precipitate a food fight. It may have been because, in their backgrounds, they were very much alike. Belushi, like Aykroyd, was from a strict Catholic background, where, it was said — though never confirmed — his father beat him. And in both, following the strictness, came a rebellion, a rage.

Whatever, Belushi trusted Aykroyd.

“He’s Mister Careful and I’m Mister Fuck It,” Belushi once said. “I can’t always figure him out, but whenever I’m with him, I feel safe.”

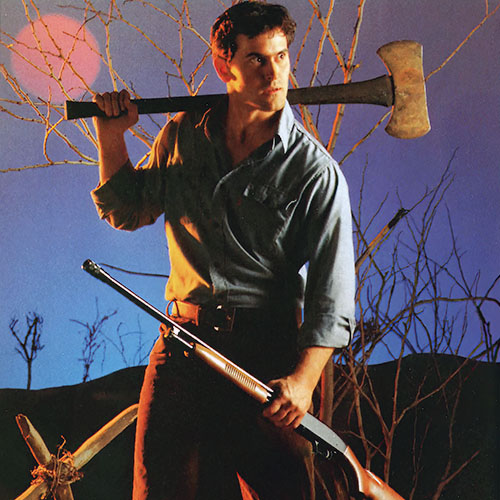

Aykroyd was interviewed on the set of his new movie, Dr. Detroit, by Allan Sonnenschein, who was also the co-author of last month’s article “The Last Five Days of John Belushi.” Aykroyd talked about his relationship with John Belushi — and his life as an actor. A film Aykroyd had been planning on doing alone before Belushi’s death, Dr. Detroit is the sort of spoof his partner would have enjoyed: the story of a college professor, mild-mannered and virtuous, who, in order to save himself from the Mob, assumes the identity of a Chicago pimp. It’s an exhausting role, a role in which Aykroyd had been working for months, but he was, on the set, ever courteous and never the star. Approached one day by an elderly extra who said he hadn’t seen Aykroyd’s work, Dan was gracious in his reply.

“I’ve done some late-night television,” he said.

A man of varied interests, he spoke with us of many things: motorcycles, cars, space travel, the occult. Music was a particular passion. A carton in his dressing room included a crate filled with hundreds of cassettes, classical to country and western. And while he shrugs off his own talents as harmonica player in the Blues Brothers, calling himself “the George Plimpton of blues harp,” professionals say otherwise. Dan Aykroyd, a musician on the set told us, could play harp with any band in the world.

There was also discussion of death in our talks. In the past year, in addition to Belushi, Aykroyd lost two grandparents and an old high-school friend. The pain of death, particularly Belushi’s death, has stirred him, for the first time in his life, toward a role as activist. He has become a director, with his brother Peter and Belushi’s widow, Judy Jacklin Belushi, of the John Belushi Memorial Foundation, which will assist social welfare agencies in the war on drugs. He also plans on devoting time to the Scott Newman Foundation, a like-minded organization named after Paul Newman’s son, who lost his life because of drugs.

The interview took place over many days, in many locations, including Aykroyd’s office bungalow, where a moose-head — Belushi’s gift — hangs on the wall.

Aykroyd was always frank, always open, never performing for an audience. There was no subject he refused to discuss. After the interview was completed, he voiced only one concern. “Do you think I came off as a cool and flip guy?” he asked. He did not.

How do you think we should remember John?

Aykroyd: I think we should remember him for his work and how great it was. We should remember him as a great artist. as a great strategist and businessman, as a soulful, warm human being who loved to impart that to people. As someone who had the capacity to take care of others, and as a really warm, vulnerable guy who had a gruff, rough exterior. And someone who could be taken advantage of very easily, because he was so trusting.

I have so many personal memories of him. I slept at the foot of his and his wife’s bed when I first came to New York. When he came up to my family’s farm to meet my parents, he got out of the car as my father was walking down the front steps and jumped up and did a flip for him! It was like, “Here I am. I’m Dan’s friend. I’ll do anything you want.” He made me laugh harder than anyone else. He was a guy I danced with. I remember little things about him every day, and they’re all favorable. I get a smile out of him every day. And I just miss him a lot and … I don’t know, you can’t dwell on it, you’ve got to go on. Life and death are intertwined. There’s a very, very slender thread that separates the two. John and I used to enjoy quoting a Ring Lardner line: “Live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.” During the last summer we were together, we wore skull pins on our shirts or blazers or jackets or whatever. We always had a skull pin on. And we sort of knew, between us, that it wouldn’t last forever, that we wouldn’t be together forever. That one of us might go before the other. John knew about my love for motorcycles and knew that I was a kind of risk-taker, and I knew that he was the same. When he died and it finally sank in, it was just like … I doffed my hat to him, “Farewell, comrade.” He was a wrangler, an adventurer.

Do you think John was just hanging around with the wrong people at the end?

Aykroyd: The people he really liked were worthwhile people. I’m not going to name names, but they were at the pinnacle of this industry — the best in music, rock ‘n’ roll, films, and television. These were John’s real friends, the people who were most worthwhile to him. And he would never have gotten into this drugged condition with them. Some of these vermin he was hanging around with at the end were talentless, worthless individuals with no specific skills or contributions to make to the world. And John could really be a monster, an out-of-control monster with them. He had to be straight with the people he held in esteem. He was respectful and more lucid in conversation and much more together when he was around people he respected. The reason he was with these other people is because they allowed any behavior.

You had no idea that John was being injected with drugs?

Aykroyd: No idea. I was really surprised when it came out that he injected himself, because I know he was not that good a mechanic. He wasn’t capable of that and didn’t like needles at all. Even when he’d get a B-12 shot in a movie, he winced. He had to have a needle put in his knee once to drain some fluid, and that put him through terrific pain and agony. Blood tests, all that stuff, really bothered him. But I guess there was something about Cathy Evelyn Smith that was soothing. I guess she had a nurse-like quality about her that made it easy for her and him to do this act together.

Did you ever meet Cathy Smith?

Aykroyd: I don’t remember ever meeting her. I’m sure that John knew what would happen if I’d known what she was giving him, and so he probably kept her far away from me.

What would have happened if you’d known?

Aykroyd: I could have gone either way. The fact of the matter is that I loved John so much that I wanted to share every experience with him. If he’d taken me into his confidence about these drugs — if he’d said, “This is something we have to try together. This is what makes it. This is what makes junkies junkies. This is what the Blues Brothers is about — we have to experiment with this. You’ve got to join me” — I might have said, “Okay, let’s do it.” Not to have a good time, not to get high, but just, “Okay, John, if you want me in on this, fine.” Or I might have said, “You’re crazy. I’m going to slap this away from you. You’re getting out of here right now, you’re coming with me.” So I don’t know. I’m not sure. It would have depended upon how he approached me. He could be a real charmer. My last conversation with him went like this:

- Aykroyd: John, when are you coming home?

- Belushi: I’ll be home Thursday or Friday, I’m not sure yet.

- Aykroyd: Well, you really should come home; we should go up to the Vineyard. And then I have something else I want you to do.

- Belushi: What’s that?

- Aykroyd: The biggest favor you’ll ever do me in your entire life, the biggest favor you’ll ever do yourself. A captain in the United States Navy has asked John Landis [the director of Animal House and The Blues Brothers] and you and me to join them on a cruise with the Twelfth Fleet from San Diego in two weeks. John, I want you to come with me on that cruise. I want you to come back to Massachusetts. I want to sit down and discuss and plan the next five years. And then I want you to come with me on that cruise and spend a week on board ship, change the life-style that we both know right now. Will you do that for me?

- Belushi: Well, that would be very hard for me to do.

- Aykroyd: Why, John? I think it’s very important that we do this.

- Belushi: Because I get seasick.

Then he handed the phone over to Bernie Brillstein, our agent. I said, “Bernie, don’t you think that John and I could use a break to just clean up our minds and bodies and psyches?” Bernie said, “I think it’s a great idea.” Bernie hung up; I called him back ten minutes later. John had left the office and Bernie said, “Well, John’s agreed to do it. He’s going to go on the cruise with you and he’s going to be home Friday.” That’s the last time I talked to John. That was the last conversation.

And then the last time I heard his voice was the day after. He called in and got my answering machine. When I played it back, he sounded really tired and like he hadn’t been sleeping. And he said he was coming home that night. So I thought, “Thank God.” And of course that night was Thursday night, and he died Friday morning.

I was all set to jump on the plane to go get him. I had spent the night before talking with his wife, Judy, talking about getting him home. He had been completely straight for the longest time. Completely clean. But then he felt depressed about working on this last project. And going to Hollywood, with all that it offered, really made him a little outrageous. I will always feel that I was one day late. That I could have done something, you know?

All I can say is that my intentions were to get him back to the feeling he was in during the last summer we spent together, and that was just enjoying the outdoors and exercise and fresh air and good diet and each other’s company. And the joy of knowing that we were away from the scene we had to live in much of the year but really didn’t like that much — the high-pressure, executive world of show business. We truly took our leisure time that last summer and it was a great time, because we didn’t need anything. We were clean and we lived on lobsters and beer and that’s about all.

People were saying that after John’s death, you turned into a recluse, started wearing John’s clothes and calling him on the telephone. Is there any truth to this?

Aykroyd: It’s half true. I do wear John’s clothes. I have shirts and jackets of his that I wear. But our clothes were always inter-changeable. When we did our Blues Brothers shows, I would get into his jacket and pants and he would get into mine. “Hey, these pants are too short.” “Oh, we’ll do the show anyhow.” It didn’t matter. I like having a T-shirt of his to remember him by, you know? John had some nice clothes. John had good taste in everything — music, people. Not drugs, though. I don’t think he had good taste in drugs. I don’t think he bought the best. Too bad he didn’t go out on the best.

But about my behavior. Yes, I wear John’s clothes, yes, I take long rides on my motorcycle alone, and yes, I spend long periods of time alone. No, I don’t get up from the dinner table and go and call John on the phone. If I was going to communicate with John, I wouldn’t use the telephone, I’d use the Ouija board. I do believe in the other world; I believe in phantasms and phantasmic gaps where ghosts might get caught between one dimension and the other. I think there’s something to all that. You only need to look up the American Society of Psychical Research in New York and ask for one of their monthly journals and you can see that there’s a very real science devoted to this study. So I wouldn’t use the telephone; I’m not that stupid. I would use a psychic medium or a Ouija board. The Ouija board really works. I’ve seen evidence of it.

I don’t talk to paintings or pictures. I haven’t gone that crazy. But I do have a nutty streak in me. I am a recluse. And my father is a guy who, when you go shopping with him in a supermarket, when you walk down one aisle to get an item, will push the cart down another aisle — you’ll be in the fourth aisle, he’ll be in the seventh. Suddenly paper towels and toilet paper come flying across the aisles. He just wings them across. So he is a bit of a nut too.

“During the last summer we were together, John and I wore skull pins on our shirts…. And we sort of knew, between us, that it wouldn’t last forever, that we wouldn’t be together forever.”

What has been your personal experience with drugs?

Aykroyd: Well, I’ve done everything. All of it. You name it, I did it. This was in my teenage years, mind you. I think I really started to clean out when I was twenty-two. But I mean I gobbled phenobarb, I’ve snorted crank. And a long time ago, a couple of times, I was injected with substances. Didn’t do it myself. That’s why the scenario of John and Cathy Smith is so vivid to me, because I remember being hit up myself for a charge when I was a teenager. I just didn’t appreciate the impairment drugs could do until I reached a certain point and realized that hey, I’d experimented, done it all, followed through with the convictions of this whole Woodstock generation — that you could do these substances, alter your mind, and it could be an enjoyable thing. I went through that like I guess a good segment of the population did in the late sixties and early seventies. It was the time of legitimized drug-taking. People who were able to shoot back a bottle of whiskey, smoke an ounce of grass, do a six-pack of beer, swallow lots of pills, and still remain walking were sort of champions in this culture. They’d say, “Hey, that guy, he’s a blast to be with. He can do it all and it doesn’t affect him.”

John was kind of sucked into this thinking. He thought that it was a measure of his stamina that he could consume what they did. And he was a big man. He ate more than many people, he drank more, he smoked more, and did other stuff too. He wanted to top everyone else and show them he was indestructible. That’s not to say he was like that all the time. I saw him in that state very seldom. I know he was hanging around with people mentioned in your article, which I’ll say here that everybody should read. Pick up December’s Penthouse and read the Belushi article! I really believe that the article accurately described what happened. I also believe that the most poignant and meaningful segment of that article is where John is with the cab driver. That’s Belushi right there. The vulnerability — “How am I doing?” Afraid that the cop would come over and say, “Hey, you’re not parking the car right; you’re not backing out right.” Offering the guy what he had. Wanting to go out and just simply smoke a joint. Opening up to this guy who he doesn’t know. You get the feeling, reading this, of a vulnerable, beautiful guy.

Why did you go off drugs?

Aykroyd: I came to the realization that we are given a pure organ here, the human body, and anything we add to it is going to be detrimental. I think it’s nicer to live life at your peak efficiency and at the peak realization of all your senses and power. And drugs do take away from that. Not that I didn’t have fun doing acid. Acid opened some doors for me, in a way, in the classic sense of Huxley and Leary and all the theorists who said that it was a mind-expanding drug. It opened me to a lot of perceptions that I wouldn’t normally have had. I wouldn’t recommend it now, because we’re living in a different era.

Why does heroin appeal so much to young people these days?

Aykroyd: Heroin is very appealing because it gives such a warm sensation, such a feeling of security. Why are there so many junkies? Why is it such a popular item? It’s obvious. But it’s just so destructive and so addictive that I think the world is getting hip to it. But it’s a billion-dollar industry — pot, cocaine, heroin. We know that a lot of Iranians left Iran, not with money or gold or bank drafts, but with junk. And they brought it here and their fortunes were turned over in American money through the junk they ran in.

How do you reconcile your negative feelings about drugs with the fact that “Saturday Night Live” had so many jokes with allusions to drugs?

Aykroyd: We did jokes about drugs because drugs are definitely a part of our culture. Many kids today know about drugs and they do them. Their parents smoke joints, drink. What are you going to do? But kids should realize that what we do on television is fantasy. I mean, when we watch Dirty Harry, are we supposed to look up to this guy with the hand cannon who goes around blowing away people? Kids aren’t stupid enough to romanticize that kind of character; neither are they stupid enough to romanticize drugs and think that getting fucked up is a positive thing.

Do you think you have any responsibility to serve as a role model to your young audience?

Aykroyd: A little bit of that is important, for sure. But then again, our role is to entertain. And if drug references make people think and laugh, then the entertainment aspect of what we do is more important than the role model aspect. Come on, now, this is the United States of America. The real role models out there aren’t movie stars and rock performers. The real role models should be the working people involved in day-to-day industry. We live in a world of fantasy here in films; this isn’t reality. It’s million-dollar make-believe out here.

Do you draw a line anywhere when you do drug jokes?

Aykroyd: I don’t think I would snort coke on the screen. I’ve come to be down on that a little bit because I know how dangerous cocaine is. I refer people to a Scientific American magazine article published in March 1982 on cocaine. Coke not only impairs your functions and blows out your synapses, it’s bad for the blood vessels, it’s bad for the sinuses. It’s an extremely destructive drug. And this new popularity of free-basing is tragic. People are admitting all over the industry now how it’s destroyed them — destroyed their finances, their work, their souls, their beings, their bodies.

Is it a big deal to you to be a star?

Aykroyd: Well, you know, star spelled backwards spells rats. Every coin has two sides. And being a star is not my profession. I wouldn’t call myself that. I think I’m an originator, a creator-writer, you know? Performer is a better word than star. But of course we operate on a star system. There’s a lot of pressure for that reason. You have to produce, and you have to be profitable for the mega-corporations that back you. That’s if you want to continue to be a star.

What if it all ended tomorrow?

Aykroyd: I could adapt very easily to doing some other things. I feel I’ve reached the pinnacle of success in this industry; I’ve had a hit movie, The Blues Brothers. I’ve worked with the great directors of our time: Spielberg and Landis, Pressman, to name just a few. I’ve won an Emmy for my work on “S. N. L.” and appeared on television and been appreciated and had people come up to me with smiles on their faces, filled with goodwill. If it all just went away tomorrow, I’ve done it.

Who came up with the idea for “Saturday Night Live”?

Aykroyd: It was Lorne Michaels, primarily. Also Dick Ebersol and David Tebet, an executive at NBC.

Did they call you for an audition?

Aykroyd: There were massive cattle calls. I went to one, saw the number of people there, and said, “I will not audition. I am not going to do a piece, I’m not going to do a reading, I’m not going to do anything. I’m going to go in and say hello to Lorne because he’s an old friend; I’m going to meet the director and then I’m leaving.” I was in the room for about a minute and a half. I wasn’t going to get lost in a sea of 150 performers. I know my talents and capabilities and limits. I know that I’m best in a one-on-one situation. If you want me to work for you, you’ve got to hire me and give me a try. I want some faith. And these guys knew my work. Lorne knew me from Second City. We talked about the show and he said, “If it ever comes to fruition, would you like to be involved?” I said, “Certainly.” But he hedged on hiring me, and he hedged on hiring John, too. And Bill Murray.

Why?

Aykroyd: Because he saw three turbulent males who potentially could have been harmful to the harmony of the enterprise.

“Pick up December’s Penthouse and read the Belushi article! I really believe that the article accurately described what happened…. You get the feeling, reading this, of a vulnerable, beautiful guy.”

So was there disruption to the harmony?

Aykroyd: All the time. I put my foot through the wall once because I felt the writers were being maligned a little bit. We’d write a piece, we’d set it, and then Lorne or Dave Wilson, the director, would come and say, “This has to be changed.” We’d end up changing, changing, changing right up to air time. And it screwed everybody up — the cue-card people, the prop people didn’t know whether they were coming or going. So finally I put my foot through the wall and said, “Hey! Let’s just do a piece and at a certain point just stop.” There was a little revolution there, but nothing that couldn’t be worked out. No grudges ever borne. Sometimes people wouldn’t agree on certain characterizations or on who should be assigned what role. The person left out of a scene might make a fuss. But these were just little things that went on all the time in the natural order of a working day.

When the show first started, did you have absolute confidence that it was going to work?

Aykroyd: No, absolutely not. I thought that we’d do seven shows and it probably wouldn’t go anywhere. But then it caught on, and the medium was there, the opportunity was there to do anything. So I jumped in and gave my all.

How did you develop the concept of the Coneheads?

Aykroyd: I was watching television and realized that people’s heads are only a certain height on the screen. And then I thought, wouldn’t it be great if they were four inches higher? And so I just drew that picture up. And after I drew that up and the Coneheads were on the show, I saw this cartoon called “Zippy, the Pinhead.” I hadn’t seen Zippy before, but he was pretty different anyway. He isn’t from outer space and he’s just a pinhead, not a cone-head. I drew the original graphic up, and then Tom Davis and Lorne and I developed it. It was done in concert — it wasn’t just one man’s effort.

Is that how most routines were worked up?

Aykroyd: Yes. It was such a terrific thing. The writer could write a piece and then just go down and produce it. He would make sure all the props were correct; he would sit there and nurse his piece along right to the air time. So every writer was really a producer. It was a real workshop. I’d work with the director, with the sound people, the camera people — I’d work on the camera angles, things like that. Everything was done with the cooperation of lots of people, but each individual writer could really carry the ball on his pieces.

Did you have more freedom doing that show than you have doing films?

Aykroyd: When you do a film, it’s pretty much rigidly scripted. But “S.N.L.” was too. It’s funny to say that, because, of course, the effect was supposed to be so spontaneous. But we’d spend eight hours just blocking sketches for the cameras — moving very slowly, taking positions, repeating lines. It was interminable. We’d spend two days of the week just standing there, moving from mark to mark, going through the action again and again while the cameras were set. Those were a really tough couple of days. So then when Saturday night came, you couldn’t possibly deviate from the script. Once the script was set and the cards were set, that was it. Do you know I never learned a line for that show? The whole thing was on cue cards. I read every word. Everyone did.

Did that ever cause problems?

Aykroyd: I remember one awful time, when Frank Zappa was on. We were doing the Coneheads scene, which Frank loved. We were all in position to do it when Frank said, “What am I supposed to do? Read these cards?” It totally broke the reality; it was awful.

Why did he do that?

Aykroyd: I don’t know. Maybe he thought he was above the whole thing or he was nervous or he didn’t like the script. Maybe he thought he was being funny. But in fact the audience sort of gasped. But you deal with that kind of thing. That wasn’t the only problem that night. The cone kept collapsing and coming down on my nose, and we were sweating underneath. We used to have to get into those things in a minute and a half.

What does it feel like when the comedy doesn’t work?

Aykroyd: Like death. Death on wheels. Terrible. Dying. That’s how we refer to it: “I was dying up there.” And let me tell you, I have died up there. My brother and I had this routine of two guys who sit down in a restaurant and instead of eating the food, they inhale it whole. So we did this shluuuuuuuuuurrrpppp inhaling thing. And it died on stage. Nobody laughed. We thought it was the greatest thing. But we kept on doing the sketch until it ended. You just commit yourself when you start a sketch; you can’t think about it midway through.

How often did that happen on “Saturday Night Live”?

Aykroyd: It happened sometimes. Oh, sometimes there would be just nothing. No response, no response. We’d finish a spot, the lights would come up, the applause sign would come on, and there was silence. We always had an applause sign, by the way. The audience wouldn’t always know when a scene ended. But sometimes they just wouldn’t respond. It might have been a result of weak material. Or maybe it was just an off night. Some audiences were a lot thicker than others. Some were real sharp, some were real thick.

When did you start getting tired of the show?

Aykroyd: I guess in the end of the third year. We started to repeat bits and do them over and over again, and the novelty was lost. And John was called to do Animal House. I was called to do Animal House, too, but chose to stay with the show to write. Films were beckoning, though. It seemed that we had to move on.

Also, it was very hard. It was a six-day work week. A hard grind, with no outside life at all.

This didn’t bother you in the beginning?

Aykroyd: In the beginning, in the first three years it was fantastic, because it was the hottest job in town. We were working in Rockefeller Plaza. There was real joy. And impact in the involvement.

Did it go to anyone’s head?

Aykroyd: No, because we knew how fast and how volatile this industry is. We didn’t hold any illusions. We thought of ourselves as cheap, late-night television actors. That’s what John and I used to call ourselves all the time. And even when we were out in Hollywood we’d say, “Hey, I don’t know why we’re on this film set. We’re just cheap, late-night television actors.” And that was fine with me. I was a cheap late-night television actor who made people laugh. That was good enough for me.

Did you have a sense all along that everything was going to work out as well as it did?

Aykroyd: I’ve always thought that certain things can be controlled, but fate is pretty random. I believe that, to a certain extent, you can direct things to happen the way you want by positive thinking. By negative thinking, too. If you want something badly enough, and you think positively about it in the tradition of Glenn W. Turner and Norman Vincent Peale, then things can happen. You can become great and do great things if you think that way. If you think negatively, negative things will occur. The wild card, obviously, is that you don’t really have any determining ability in being able to plan everything.

Do you feel you’ve reached a kind of plateau now?

Aykroyd: Well, it’s still an uphill climb, you know. It’s still a struggle. But I’ve been very fortunate so far, no question. I try not to predict what’s going to happen in the future. I never did have any preconceived notions about what I was going to do. Although, when I was twelve years old my parents put me in improvisational classes. And in the back of my head I kind of figured that if I stayed with this, I’d end up in Hollywood doing movies. It wasn’t exactly a wish. It was like, “Well, the logical development of this kind of work is the film industry.”

“The perfect woman has a bachelor of science in mathematics, flies an F-16, is a millionairess, and owns a liquor store.”

Why did your parents enroll you in improvisation classes?

Aykroyd: They saw they had a hyperactive kid who needed direction. I wasn’t interested in sports. I had a drum kit, but that was the only musical outlet I had at that time. So they saw that they had a kid with a fast rap and a big mouth, so they put me in classes with other kids like that.

Do you think your fast rap ever gets you in trouble?

Aykroyd: Oh, I sometimes put my foot right in my mouth, no question. I’m sometimes too frank with people — too open and too frank and too straight. I believe in the cards being above the table and I don’t bullshit around. I hurt people’s feelings sometimes. Sometimes I can make real mistakes that way, too. The biggest mistake I probably ever made was when the rock group Devo came to me at “S.N.L.” and gave me their tape. This was two years before they appeared on “S.N.L.” I looked at it and I said to the rest of the staff, “Now, I’ve just seen the worst tape I’ve ever seen. These guys are nuts. I don’t know what they’re trying to say, what they’re trying to communicate. Does anybody want to look at it?” On my recommendation, they all said no. Two years later Devo was the biggest group around. So I delayed their appearance on the show, and perhaps their careers, just because I felt strongly that this was not the type of material that should go on the show — and said it. After I left, the tape was on in a second. They screened the very same tape I looked at.

Did you change your opinion of the group?

Aykroyd: Yeah, I think their music is quite valid now. I like it a lot. Maybe I helped them! Maybe I helped their timing; maybe they wouldn’t have broken that well two years earlier than they did.

Do you like rock music in general?

Aykroyd: Oh, yeah. I love all music. Everything.

Did you take the Blues Brothers seriously?

Aykroyd: Well, we thought it was parody at first, but then we started to get in with these heavyweight musicians and we realized, “Hey, we’ve got to be pros here.” I had to learn how to play harmonica, and I now consider myself the George Plimpton of blues harmonica. That’s as far as my ability takes me. Although some would say that I can play decent rhythm harp and I can jam with a sax. You put me in with a horn section, I’ll fit right in. No problem.

I’m not good playing lead harp. There are much better people around: Kim Wilson of the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Curtis Salgado, who used to play with the Robert Cray Band, Pat Hayes of the Lamont Cranston Band, Donnie Walsh of the Downchild Blues Band. I admire and love all of their work.

What comedians do you admire?

Aykroyd: Phil Silvers, Jackie Gleason, Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz. These are the ones I learned from. If I were to give advice to young people who want to get into this business, by no means would I encourage them, because it’s really rough and it takes its toll. But it can be the best business in the world. You can be extremely successful and make a lot of money and gratify yourself artistically in this business like you can in no other. In what other business in the world can you invest $10 million and make back $7 million? This is it.

Are you concerned about doing a movie without John?

Aykroyd: I know I can carry my own. I know that this project is tailored to me. I think it shows off a lot of my abilities. I feel very secure about the project. Obviously I miss having the other motor home nextdoor playing loud rock music. I miss all the fun it was to have him around.

Would you like to do a straight role?

Aykroyd: It’s not a burning desire. I think I’ve got to ride the peak of comedy for now. I don’t think people would be interested in seeing me in a dramatic piece. And I like doing this. I like doing roles that are based in reality, rooted in reality, but then take off from there and get weird and far out. I like it when the tether to earth is cut halfway through the picture.

Do you think films display your comedic talents more than television?

Aykroyd: I don’t know. I think both mediums do it well. Certainly in television I could do more, more concepts, more free thinking.

Do you think some of your memorable television pieces could sustain a movie — the Coneheads, your portrayal of Nixon, the “wild and crazy guys”?

Aykroyd: I think so. The Blues Brothers were just a musical bit on “S.N.L.” and they sustained a movie. And I really think Steve Martin and I should take the wild and crazy guys through to a movie. We’ve discussed it. I think it’s definitely in the future.

What is the Dan Aykroyd philosophy on women?

Aykroyd: I wouldn’t say I have a philosophy. I wouldn’t be so bold as to assume that I could philosophize about such a complex and excitement-filled entity as womankind. I have this to say about women: I’m aware of the male and female sides in all human beings. I have a strong female side. That would be the instinctive, the intuitive, the perceptive side. I think women have a special skill in these areas somehow.

As far as my relationships are concerned, I’m totally heterosexual, always have been, always will be. I’ve made a decision not to marry or have children. I intend to remain single for life.

Even if you meet Ms. Right?

Aykroyd: I have special women friends who I keep in contact with. A very few. I’m discriminating. I’m not promiscuous by any means. The women with whom I have relationships are women who like a one-on-one thing. And I am capable of loyalty when I’m together with that woman. If we’re in different countries or cities, then I don’t think that loyalty is practical. If it’s for a day or two days or two weeks, then fine. But beyond that, I like to explore new relationships. And I appreciate womankind. I love the company of women. I sometimes prefer the company of women to men, just in terms of sitting and rapping with them. Listening to what they have to say. They take me into their confidence, I think. They get kind of a vibe about me that I’m not into the conquest or the macho thing.

Has there been a great love in your life yet?

Aykroyd: Well, my first one, when I was seventeen.

What happened?

Aykroyd: We still see each other. We keep in contact and get together at least once a year. And that’s a true joy in my life. I want to open up a little more to her, too, but it’s hard, with my time schedule. It’s tough.

Has a woman ever broken your heart?

Aykroyd: Yes. I’ve been burned badly three times. I would say I got over all of them except one. I don’t know if I can be in the same room with her now, it’s that bad. She’s a real blueblood, that one. An English woman of extremely good breeding and charader. I think I was a little below her station in life.

And I almost got married once. I’m still friends with that girl. She’s very special. She didn’t burn me. Perhaps closer to the end of life I might consider some kind of permanent relationship with her.

Do you have an image of the perfect woman?

Aykroyd: Sure. The perfect woman has a bachelor of science in mathematics, flies an F-16, is a millionairess, and owns a liquor store.

“I like doing roles that are based in reality, rooted in reality, but then take off from there and get weird and far out. I like it when the tether to earth is cut halfway through the picture.”

What does she look like?

Aykroyd: Well, you know, I like beauty, but I see beauty in conversation; I see beauty in the eyes before I see it anywhere else. Obviously, I like the type of woman that appeals to the average male, like the type that appears in Penthouse — but I’m flexible. But discriminating. Very discriminating. And very careful. I must say, one has to be very careful in today’s world of sexual encounter, not to pick up any questionable ailment. And so far I’m safe.

Some people think that the fear of contracting venereal diseases is turning people off to sex.

Aykroyd: I think people are being a lot more careful now. And I will say this about myself: I am perfectly willing to take the responsibility for contraception on myself. I think that the Pill is bad for women. I know many women who can’t take the Pill because it affects them in an adverse way. We know that coils hurt women inside; they’re not organic. The oldest method known to man is the safest — the sheath — and consequently I have been a purchaser of some of these products and I swear by them. I think a woman appreciates a man who is willing to take on that responsibility. And I’m perfectly willing to do that.

If the perfect girl came along, you wouldn’t change you mind about marriage?

Aykroyd: I am pretty well set on a single life.

Does that affect your relationships?

Aykroyd: I’m honest about it. I mean, I’m capable of love and affection and tenderness and openness and all of those things. As far as a long-term, year-to-year thing goes, I’m capable of that too, but not all the time. I’m not going to be beholden to just one woman. I’m not going to be tied down. I can’t be exclusively possessed by someone or a possessor of someone. I’m quite honest and truthful about this. I have to have my space to be alone. I have to be alone six or seven hours a day to write. And I don’t think I am in a business or a life-style that is contributive to sustaining a relationship. It’s just too hard. I see too many of my friends who have been divorced, some with children, and that’s tragic. So if a woman wants to know me on that basis, I will be her friend for life, I will be a companion, I will be there for her if she needs anything. So what all this may mean is that I might sacrifice continual warmth and companionship and may end up a lonely old man, but I’ll be a lonely old single man. I’ll be a lonely old guy of my own free will, a lonely old free guy.

What about children?

Aykroyd: Well, I’m going to be an excellent godfather and uncle, but I will not be a father, I’ve decided. l’ve seen sons and daughters of show business people who suffer from all kinds of psychological problems. I don’t want to put the stigma of a show business name on someone else. My work will be around after I’m gone; if I had children, they would have to deal with the “Oh, you were his son” syndrome. The kid would have to go through life bouncing off my past. It’s not fair.

Also, I couldn’t set up a home life for a child. “Hey, where’s Dad?” “Well, he had to go off to Chicago to hear a blues band.” “Who are you?” “I’m the new maid.” I wouldn’t want to lay that on a kid. And I wouldn’t want to drag the child screaming all over the world or wherever I’m going.

Other successful, busy people manage to overcome these problems.

Aykroyd: Sure, I have some friends that seem to be doing all right. I see some good family situations. But I think I move a lot faster and more frequently than these people. I can’t be in one place longer than a month without moving, without just getting away for a week. I have to keep going. Like Richard Pryor, when he caught on fire, he ran down the street and kept running, and that kept him alive. To me it’s not as extreme a situation, but in life I have to keep moving — changing circumstances and sights and sounds. And even if they’re sights and sounds I’ve seen before, I’m on a rotating drum that I have to keep moving on. And that keeps my juices going; it keeps my energy up. I don’t spend idle time very well.

Have you always been like this?

Aykroyd: Yes. I was incredibly hyperactive as a child.

Did it get you in trouble?

Aykroyd: Yes, I was a little bit of a discipline problem in school. God bless the priests who put up with me and tried to put me in line.

You were a practicing Catholic?

Aykroyd: Oh yes, absolutely, up until the age of seventeen. It’s still a big thing with me. I do have some belief in a supernatural being, although I don’t know exactly what form it has. I live by the Ten Commandments. Even if you’re not religious, they’re a pretty good code to live by.

What happened when you were seventeen?

Aykroyd: Well, I don’t know. I just fell away from the Church, from the organization of going to Mass every Sunday. But it’s something I could go back to. I could feel very comfortable at Mass, watching it all and communing with people like that. The Catholic Church has a great sacrament, and that’s confession. It’s like a free psychiatrist for five or ten minutes.

Is there anything you would like people to know about you that’s not now known?

Aykroyd: That I’m a pretty regular human being and I’m approachable, and that I don’t mind people coming up and talking to me. That I like feedback and I relate to the common man — I mean the common mass of humanity. I am one. We all are. I relate to that concept that humankind is interconnected. And that individuals are like snowflakes. Beautiful, inside and out, for the fact that they exist in and unto themselves and also that they are linked, that we are all linked. I want people to know that that’s the way I think. I’m not on some pedestal looking down. I am on earth, with my feet planted firmly on the ground. And that movie stars and all that stuff is just a job and an occupation. That people should really realize that it’s fantasy, what we’re making out here, and that in the real world other things exist. And that I want to be taken, at face value, as a real human being who is capable of communication and warmth and love and charity. That’s what I’d like people to know.

This was all 40 years ago, remember, and it would be safe to say that Dan Aykroyd moved out from underneath the John Belushi shadow just fine. Sadly thebluesmobile.com appears no more, but he bops around on Twitter — albeit rarely. He has an equally passive facebook account. Of course he has a new Brother for the Blues when the mood strikes him. The scroll down him IMDB page takes forever, but did leave us with one firm belief. If something weird happens in our neighborhood, we know whom to call.