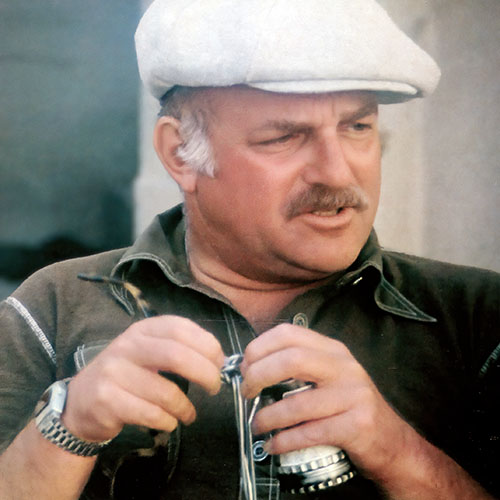

Meet the man behind “NYPD Blue’s” lumpy, sarcastic Detective Andy Sipowicz.

Penthouse Interview: Dennis Franz

The clouds still haven’t cleared from last year’s monsoon of publicity over Dennis Franz and “NYPD Blue.” Even before its debut in the fall of 1993, this edgy new cop show from ABC was kicking up a storm. First there came word that the series would push into realms of nudity and rough language previously unheard of in prime time. The prospect of that — of what Executive Producer Steven Bochco was calling “the first R-rated show” on network TV — agitated groups like the perennially agitated Reverend Donald Wildman and his American Family Association and scared off some ABC affiliates (43 of the network’s 225 stations refused to carry the show during its first season). Then, following that flap, there came a second gush of stories — this time adoring pieces about series star David Caruso, whose redheaded mug was suddenly everywhere.

Now, like a tortoise gradually gaining on the outside, comes Caruso’s costar, Dennis Franz. In his role as the lumpy, sarcastic Detective Andy Sipowicz, Franz, 49, is finally getting the notice he deserves. On “NYPD Blue” he gives an original and stinging portrayal of a man in trouble. This cop isn’t just a tough guy — he has the hunted look of an introvert. Fans of the show have also developed a rooting interest in the fumbling romance between Sipowicz and Assistant District Attorney Sylvia Costas (Sharon Lawrence). At last, a love affair with fear and bile in it — something real people can relate to.

“I don’t think ‘NYPD Blue’ is a violent show. The emotional consequences of violence are always great. It’s a very moralistic show.”

Like Sipowicz, Dennis Franz has a street-tough side and a private side. If there were a town called Mental Health, however, Sipowicz would be outside it, lost on the freeway. That’s not so with Franz. The actor has a genial light in his eye and a powerful handshake. He has a solid relationship of 12 years with his girlfriend, Joanie Zeck (the two live in Bel Air, where he has helped raise her two teenage daughters). This seedy and sallow thing he does, that’s acting.

The only son of German immigrants, Franz had a scrappy but stable childhood growing up in Maywood, a suburb of Chicago. After graduating from Southern Illinois University, he spent a watershed year in Vietnam as an army corporal with a reconnaissance unit. He went in, he says, “a frivolous young man,” but after enduring the death of friends in combat and moments when he lay on the ground literally shaking with fear, he returned home changed.

His acting career began in earnest in the mid-seventies, with a five-year stint as a member of the Organic Theatre Company of Chicago. The troupe often developed its own plays — “It was the most creative time of my life as an actor,” Franz says — but in 1978, several members of the group, including Franz, Joe Mantegna, and Meshach Taylor, headed for Los Angeles. Mantegna wound up as a prominent film actor, Taylor in TV comedy (“Designing Women,” “Dave’s World”), and Franz was slotted into a Hollywood career playing mostly cops.

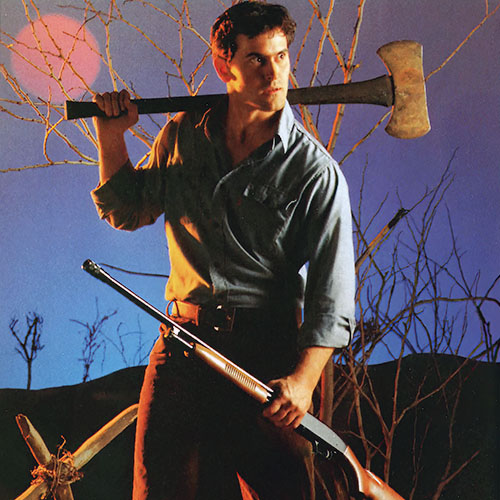

In fact, Franz has, by his own count, played 28 cops in his career, in a slew of projects from TV’s “Police Story” to the big-budget movie Die Hard 2 with Bruce Willis. The nadir, according to Franz, was a TV pilot for something called “NYPD Mounted” (which sounds even sexier than “NYPD Blue”; it was, sadly, about cops on horses).

The cop show that lifted Franz out of the ruck was the legendary “Hill Street Blues,” where he began his association with Steven Bochco and David Milch, co-creators of “NYPD Blue.” Actually, Franz played two police officers on “Hill Street”: First, in a five-episode run during the 1983-84 season, he was Detective Sal Benedetto, a cheerful sadist in a long leather coat who wound up blowing his brains out in a bank vault. The character was a big hit — TV Guide voted him Villain of the Year. The producers wanted Franz back, so eventually, Benedetto morphed into the popular Lieutenant Norman Buntz, who was featured on the show’s last two seasons — a rogue detective with the worst wardrobe this side of a clown college.

Now comes Andy Sipowicz, Franz’s crowning cop. Franz does say he’s grateful for the new challenges “NYPD Blue” has offered him. (One he has yet to face is playing a nude scene, but every once in a while, the body-makeup lady shows up on the set and, like the Angel of Death, one day she will come for him.) Even so, when this series finally slips into history, Franz hopes to retire his badge. He wants to play something besides a cop. He figures 28 is enough.

First scene, first episode of “NYPD Blue”: You grab your crotch and snarl at prosecutor Sylvia Costas, “Ipso this, you pissy little bitch.” After that, the two of you wind up in the TV romance of the year. Was it planned that way from the beginning?

No. At that time it was not intended that Sipowicz and Costas would have a relationship. In fact, that was not even supposed to be the first scene of the series. But after we had filmed it, the producers liked it so much, they thought it sort of set the tone for the whole series, so they put it up top.

So how did these two characters get involved?

I’m happy to say that was my suggestion. I’d played 28 cops, and not one of them had ever had a love interest, so I was really looking for one. I like relationships between characters coming from entirely different places, and when I brought it up, the producers immediately said, “Great idea. Let’s go for it.” That was around the seventh or eighth episode. Sharon’s pretty thrilled about it, and I am too.

It’s proved to be everything I thought it would be.

Shooting that first love scene in Sipowicz’s apartment must have been a change of pace for you.

I loved that scene. I loved the difficulty of playing it. It’s true, I don’t get to play too many love scenes, so it was awkward for me. But I was able to use that. Sipowicz is an extremely closed man, very concealed about his feelings, so it’s very awkward for him, too.

As originally written, that scene had us in bed rolling around in the nude together. Then the rewrites came down, and what it turned into was simply Costas taking her top off and me flipping off the lights — which I thought was really sweet. I liked that. I liked the sensitivity of this guy, being embarrassed enough that he has to turn the lights out. I liked his respect for her.

Was that the toughest scene you’ve had to play on the show so far?

No. It was the pilot episode, where Sipowicz is in such a low state, where he’s out of control and can’t ask for help. And then some of the fight scenes are exhausting, just on a physical level. I had a battle with [mobster] Alfonse Giardella, played by Bobby Costanzo, in the pilot. I stuff a $100 bill in his mouth, then I stuff a sock in his mouth, then I take his wig off and jam it in his mouth. Then I jump on his back. We end up falling in a sandpile, and we’re throwing sand at each other. And then I jump on top of him again and start smacking him.

Stuff like that is exhausting, but it’s also fun to do. We were like two big kids. In fact, when we were watching it back on the replay, Costanzo said, “We look like two out-of-work sumo wrestlers.”

When I played Benedetto on “Hill Street,” I grabbed a guy’s nose in a pair of pliers. I pushed another guy’s face in a plate of spaghetti, and then I threw red wine on him. It’s fun on both sides. If I’m the guy getting smashed, that’s fine. If I’m doing the smashing, that’s okay, too.

Is it a good outlet for your aggressions?

Absolutely. Without question. I do get to release my frustrations through these guys I play. It saves a lot on my home life.

Are you a good fighter in real life?

Yeah, I can handle myself. I would always rather not, but I grew up in an area, a suburb of Chicago, where you had to. You had to learn how to use your fists. You had to be able to defend yourself.

Do you have the same problem that, say, Humphrey Bogart used to have, when people who have seen you on TV spot you in a bar or something and want to confront you to see how tough you really are?

I’ve had that a couple of times, especially when I first started getting visible. People thought maybe that’s the way I am, and they’d want to challenge me. When it first started happening, I thought, Am I going to play into this? Am I going to be this kind of guy all the time, always aggressive? I knew in my heart that’s not what I’m most comfortable with. I’m a lot less confrontational than the characters I tend to play. I’m more passive. I walk away. So I just had to make a decision early on that I was going to be myself, and if it disappoints people, so be it. I can always do the bombastic sort of character. I can pull it off. But I’m not that guy.

Of course, “NYPD Blue” is famous, or notorious, for pushing the boundaries of what’s acceptable on network television. Let’s take language, for instance. Obviously, there are still some words you can’t use. Is there a list somewhere?

Evidently, there is. Shit, fuck, goddamn — those three for sure. I was surprised when I heard prick. But I guess after asshole, prick is soon to follow.

I used up one show’s whole quota of assholes in one particular scene. Kelly [David Caruso] and I are racing somewhere, and a car cuts us off and we smash into him, and this drunk driver gets out. He says, “You asshole.” I get enraged and jump on his hood and kick out his windshield. I just went off. There was no dialogue written, nothing. I just climbed up on the hood and started jumping and going, “I’m an asshole? I’m an asshole? I’ll show you an asshole, you asshole.” I used asshole maybe ten times. And then I kicked in his windshield. That was not supposed to happen; it was an accident. But as soon as I broke it, I thought, Well, they’re stuck with this take. They’ve got to eat all these assholes.

Isn’t there something kind of unreal about how the lines are drawn now? That somehow douche bag is okay, but shithead isn’t?

It is odd. A word is a word. There was this one word we used — goonya. I had a line, something about “bouncing around in your goonya.” Somebody at the network got up in arms about it. They said, “You can’t say ‘goonya’ on TV.” And Milch says, “What are you talking about? I made up that word. It’s not a real word.” They said, “Yeah, but the way Franz says it, you can’t use it.” They fought over it. Eventually, we got it on the air.

What are the exact rules on nudity?

No pink. That’s the rule. No nipples. No genitals. Butts are okay. Don’t ask me why. And even that, they try to put limitations on the use of that, and Bochco and Milch will agree to that. They don’t want to just be gratuitous. But if that helps them in telling their stories, that’s a color they can use.

There’s a nudity clause in all the principal actors’ contracts?

Yes. If requested, we agree to appear naked. I was very flattered. I said, “Absolutely. I’ll sign.”

“Some of the fight scenes are exhausting … but it’s also fun to do. It’s fun on both sides. If I’m the guy getting smashed, that’s fine. If I’m doing the smashing, that’s okay, too.”

How do you feel about the Reverend Donald Wildman and his American Family Association?

Well, I owe him a lot. He made the show a huge success. At least he was instrumental in that, in the immediate success of it. Do I disagree with their concerns? Not entirely. On the other hand, this is still America. We still have a choice. We still should be allowed freedom of speech. And it’s our choice, hopefully as responsible adults, to either approve or disapprove of any particular artistic offering. That’s exactly what this is. Wildman has every right to make his statement and to try to get others to see it his way. I do appreciate his concerns about the state of entertainment, but I don’t agree with his encouraging people to not be allowed to have a choice in this. There are people who made decisions without even having seen the show. They were afraid of the concept of “NYPD Blue,” and they got on the bandwagon and protected their communities by not allowing them to see it. I don’t think that was responsible on their part.

Let’s go back to the role that put you on the map — Norman Buntz on “Hill Street Blues… How did you come to play that?

They asked me to come back to “Hill Street” a couple of years after playing Benedetto, but I didn’t know what I was coming back as. The first thing they told me was he was going to be German, so I started thinking of German names. Like, my mother’s maiden name was Mueller, and I was thinking, That’s a good, strong name.

Then one of the NBC guys called one day and said, “I have your name.” I said, “What is it?” He said, “Norman Buntz.” I thought he was kidding. I said, “They’re not telling you the truth. They’re joking.” So I called up David Milch and said, “David, what’s with this Norman Buntz stuff?” He said, “Yeah, pretty great name, huh?” I said, “Great? It’s goofy. What kind of name is that?” He said, “If a guy’s got a name like Norman Buntz, he’d have to defend it from the time he was a kid. It would give him an attitude.” And I said, “You know, that’s interesting. I can use that.”

Then came wardrobe. I show up for a fitting and see all these horrible-looking polyesters, all these mismatching clothes. I said, “No! No!” I went to Milch again. “What’s with the clothes?” He said, “What, you don’t like the clothes?” I didn’t. I thought, Buntz is turning into a mutt.

Later on, I did learn to appreciate the wardrobe — the polka dots, the plaids. I got into it. It was something else for me to play. I still thought a couple of the sports jackets were on the borderline of being Arthur Godfrey. But when I was given a choice of ties each week, I would go for the one that matched the worst.

In fact, I started receiving ties from viewers. I tried to use them on the show. The best one I got was a green paisley tie. If you looked at it real close, you could see that all the little paisleys were psychedelic lettering that read, FUCK YOU. FUCK YOU. FUCK YOU. That I never wore on the show. I thought, Mmm, if I do and they catch it, there’II be a price to pay.

What was your favorite episode as Buntz?

The one where Buntz was taken hostage and tied to a chair. That was pretty strong. It was this mental jousting match that I had with this crazy man — trying to hide my own fears and my concerns, but also trying to protect my partner and talk him into doing the same thing I’m doing. The thing is, don’t beg. The guy got so frightened that he found himself cracking and begging. As soon as he begged, it was over.

What about the line from that episode, “It wasn’t tea with the freakin’ queen”?

That was kind of a ground-breaker, the use of the word freakin’. I think I was the first character that used the word freaking. And then I started seeing it popping up all over, and I wanted to lay a claim on it, like, Hey, hey, that’s my word.

Did you ever campaign to get Buntz a girlfriend?

Yeah, I did. I wanted him to have a black girlfriend. The guys I play are usually interpreted as being prejudiced or racist, and I thought, How interesting for somebody like that to have to come to grips with a relationship with someone he’s supposed to be prejudiced towards. It’s a wonderful conflict. And I’m not talking about a dropdead beautiful black girl. I wanted to see him with an average-looking person.

That kind of thing, a black-white relationship on television, it’s been done since then. But at the time, I think it would have had a profound impact on the audience. “Hill Street” broke rules, but for whatever reason, they chose not to break that one. I believe they thought it was still a taboo.

When I had the spin-off, “Beverly Hills Buntz,” I brought it up again. I said, “Give him a black girl.” They said, “Naaah, you’re going to limit your appeal.” I brought it up again for “NYPD Blue.” It was dismissed again. Then I suggested getting involved with the Costas character. It serves a similar purpose. It’s not a likely relationship.

[Laughing] The other day I was having a conversation with David Milch about something entirely different, but I was talking about relationships, and I said, “You know what would be interesting?” And he cut me off. He says, “Don’t tell me you want to jump in the sack with a black girl. You’re on record. I understand you want it. It’s not gonna happen, okay? Forget about it.”

Are Andy Sipowicz and Norman Buntz two completely different guys in your head?

They are now, yes. When I first looked at the Sipowicz character, I had a concern about similarities, but I’ve realized that Sipowicz can go over the edge. He has gone completely out of control. Buntz had such inner strength, he always knew where the line was. He might dab a toe over it, but he wouldn’t cross it. Andy will jump. And Sipowicz is a man who feels awkward in society in general.

I’m sorry Bobby Costanza’s character got killed on “NYPD Blue,” and I think others are also. Giardella was an interesting character to have around. A great foil. I wish he had survived for that, if nothing else. Find out the roots of Sipowicz’s obsession with getting him. I’m using him as one of the reasons that Sipowicz went off the deep end.

The comic opportunities aren’t as broad with Sipowicz, either. They’re there. I do get to use some choice language on “NYPD Blue.” I get to say things like “wig-wearing hump.” That’s one of my favorites. And on the show about the guy whose Oscar was stolen, I used “whip your skippy.” I said, “Some guy’s whipping his skippy gazing at your Oscar.”

You’ve worked closely with Steven Bochco and David Milch off and on for ten years now. They must know you pretty well. Are elements of you being written into Andy Sipowicz?

There’s been an evolution process that began prior to my involvement in “NYPD Blue.” The Sipowicz character was written for me. I was asked to be involved in the show a year prior to actually filming and six months prior to having any script. There was no title; there were no storylines other than the concept of a gritty cop show.

They approached me, and I welcomed the opportunity to work with them again. They already had a track record with me as far as what they like to see me do, the kind of characters that would suit me. So that evolution really had taken place before the beginning of Sipowicz. They already had the bullets to load the gun with, and they loaded it and gave it to me.

There is a personal side of me that is sneaking into the Sipowicz character — this not-so-sure-of-oneself side that they have learned of me personally. I can sometimes be reserved and quiet. I think I tend to be a little… not reclusive, but less outgoing. I think they’ve witnessed that, and they’ve found a way of incorporating that into Sipowicz. Since I usually play guys who are so sure of themselves, it’s very interesting for me.

Aside from finally getting yourself a girlfriend, do you and the other actors often contribute to the storylines?

Yeah, it happens quite frequently. There was a storyline about a Vietnam vet recently, and they asked me to give them some ideas of my experiences over there.

What did you tell them?

That I have a hard time remembering what it was like.

What do you remember?

I remember the plane on the way over. There was a lot of noise, a lot of fun on board, until we realized we’d crossed the border and we were over Vietnam. Then a hush fell over the plane. All these GIs, everybody was looking out the window and kind of reflecting. There was a quietness. You could see little puffs of smoke over this beautiful landscape. You’re thinking, Now what happens? Do I Jump off the plane and start shooting? The plane lands, you get off. The first thing you’re confronted with is this heat — and the cheers from the soldiers who are there waiting for that plane to take them out of the country. You’re their replacement. So you get this strange kind of greeting, and then you’re swept off into different areas.

You worked reconnaissance? What did that involve?

Setting up ambush. Fighting the physical discomforts of lying in water beside a rice paddy throughout the night with these bugs flying around. Thank God for the insect repellent. You put this stuff on, and you hear throughout the night this horrible buzzing noise. But you can’t see anything because it’s pitch black except for when there’s a burst of fire in the distance or some moonlight, anything that lights up the sky. Then you could see these massive insects trying to get into you. And if you ran out of this repellent, you were sunk.

Those were just the physical discomforts. The emotional thing is leaving your family and your loved ones, everybody you care about, knowing that you’re not going to see them for a year and that this is going to be your existence instead.

You’re wet at night. You dry out during the day. Your boots become so uncomfortable that when you take them off and start scratching, your feet literally bleed.

And that’s not to mention when you have enemy contact. Gunfire would open up. You’d have to shoot at people, and people would shoot at you. You wouldn’t even see people all the time — you’d just hear the gunfire and know it was at you, and you’d shoot at the area that you could see muzzle flashes or tracers coming from. We shot into areas, and we would go look for bodies when the shooting stopped. Many times we would not find bodies. Many times we would. I personally never saw a bullet from my rifle hit a person, but you don’t know who is responsible for what.

You lose friends. The buddies you’re with, they’re your whole world. And when you lose one or one gets wounded, it has a strong impact. I don’t know what to equate it to. Maybe going to jail. That might be as bad or worse, I’m not sure. But it was a year that I didn’t experience anything good except for my total respect and admiration for the men that I was with.

In the years since, has your time in Vietnam affected your work as an actor?

I’m certain it’s had an effect. I can recall some of the fears that I had at times there when I thought it was all over for me. I consciously reflect on that fear sometimes. And there have to be many unconscious choices I make as an actor that are related to that experience.

You became an actor in Chicago when you got out of the Army?

Yeah, I joined the Organic Theatre Company. I was very, very content there.

When did you play your first cop?

The first cop I ever played was in a stage play called Cops, by Terry Curtis Fox. Joe Mantegna and I played policemen. In the middle of the play, mayhem jumps out of nowhere. Shooting erupts. We had stuff rigged that would explode so it looked like we were shooting real bullets. Some people in the audience would run out of the theater.

When we were preparing to do that play, Joe and I would hang around with some of the Chicago police officers. They would take us out in patrol cars. We’d go to restaurants and bars they would frequent and just try to emulate their behavior.

Then Joe and I would go out and test ourselves on the street. I was driving my father’s old Chevrolet, which could be interpreted as an undercover police car, and we would drive around and get into situations — not pull a badge or anything phony like that, but we would confront people and say, “What are you guys doing here? You supposed to be here? What are you up to?” We’d do this just to see if we could enforce authority. And we could.

What other actors do you most admire?

My favorites are Gene Hackman, Robert Duvall, Morgan Freeman. They’re not necessarily typical leading men, but I believe every word that comes out of their mouths. I got a chance to work with Gene Hackman in a movie called The Package. I played a cop for a change. Working with Gene Hackman was the greatest experience I’ve had acting. I learned a lot about honesty. I couldn’t tell when his talking stopped and his acting began. It was very interesting. It had a good effect on me.

Do you try to bring this same kind of honesty to playing Sipowicz?

I try. We have a very limited period of rehearsal. We’re doing 22 episodes a year, and we pay very close attention to detail for a television show, but we don’t have the luxury of being able to get things perfect. We’ll finish one script in the middle of an afternoon and ten minutes later begin the next script. A new director with a new team comes in, the old team goes. You change your clothes and jump into the next storyline. It’s a different type of discipline. It can be difficult.

What’s it like working with David Caruso?

David’s an extremely intense actor. He believes, as we all do, in striving for honesty and truth in his performance. And he’s very hard on himself in trying to get to that. If he feels one false moment, he’s not satisfied, and he wants to start again. That’s film acting. That’s the kind of investment you’re able to make in film. He’s realizing that’s very difficult to do in a series, but his performance shows the type of quality that he invests in his work.

I’m not quite as hard on myself as he is. I’m able to let things go. David really gets down on himself if he doesn’t get his performance exactly right.

After all the crime dramas you’ve been involved with, what’s your feeling about violence on TV and in movies? Do you think it can prompt some people in the audience to commit violence themselves?

Yes, I think it affects certain elements of our society in a way that’s not necessarily healthy. This may sound odd coming from a guy like me, but I do not condone violence or body counts for the sake of entertainment. We’re living in dangerous times. I wish our entertainment was not in the form of violence, not in the form of sensationalistic, voyeuristic kinds of things on television or in entertainment in general. Gone are the days when entertainment would make you smile and not affect society. I think there is a certain impact. I think we both reflect one another. I think the society reflects entertainment and the other way around.

“The country was not blessed with seeing my ass the first season, but Bochco [said] recently that my time is coming. So probably next year.”

I don’t think “NYPD Blue” is a violent show. There are times when violence will erupt on it, but it’s not gratuitous. It’s done so that the impact of that violent outbreak, its effect on the characters, can be explored. The emotional consequences of violence are always great. It’s a very moralistic show.

The bulk of my mail is from police officers. I get a lot from law-enforcement officials around the country. It’s all favorable. A lot of it is appreciative of the show in general, saying it’s good to see an adult drama on television, an intelligent show that treats adults like adults.

As opposed to, say, Die Hard 2?

Exactly. Which I was a part of. I put food on the table. I would rather not be involved in that kind of thing, to tell you the truth. I’d rather not have to contribute to that form of entertainment. But I’m an actor and a realistic human being. That’s what’s being offered, so what are my choices? Either I do it or quit the business.

Is your choice of roles expanding now with the success of “NYPD Blue”?

Yes. A lot of people still insist on offering me police roles and heavies, but I have got to get away from this cop thing. I would like to show people I’m capable of doing other things. After “NYPD Blue” is finished, I don’t want to wind up playing an old Southern cop. So I’m looking at scripts. Anything that’s not a police officer I’m looking at.

Of the parts you’ve played throughout your career, what’s your favorite that wasn’t a cop?

On “Civil Wars,” another Steven Bochco show, I played Murray Seidelman, an appliance salesman who went to Graceland with his wife and became inhabited by the spirit of Elvis Presley. He thinks he is Elvis. I had a big wig and big glasses — probably just the tip of my nose was showing. It was the most delightful experience I think I’ve ever had as an actor.

What do you do to get away from acting? Do you have something that you use as an escape?

Yeah. I love to play golf. I started playing when I moved to L.A. It was frustrating at first. I was a club thrower. I broke many a club. I remember taking out a sprinkler head once — I got so upset I had made a bad shot, I threw my club further than I hit the ball, and then I went over to this sprinkler and started kicking the shit out of it, and it finally busted and the water sprayed straight up in the air. I got into a fight on the golf course once with some guy. Got my finger broken.

But I’ve mellowed as the years have gone by. My handicap is about 13 right now. It’s been as low as eight. I’m capable of a good game, but it’s going to take me a week or two of constant play to get back into single digits.

What I like about it is that when I’m playing golf, I forget “NYPD Blue,” I forget my agent, I forget Joanie, I forget my personal problems. I love being outside. I love hitting that ball.

Anything you can tell us about what’s in store for Sipowicz in the second season? Will your nudity clause kick in?

I think so. The country was not blessed with seeing my ass the first season, but Bochco made an announcement at a gathering recently that my time is coming. So probably next year. I’ve told them to promise me they’ll give me at least a month’s notice so I can get in some kind of shape.

The Franz ass notwithstanding, throughout Hollywood history, any of us would be able to create a short list of actors seemingly born for a role they ended up playing. In our quick — and completely unscientific — pole, for example, we came up with Schwarzenegger as the Terminator and Ron Howard as Richie Cunningham right off the bat. Almost everyone included “Penny” in there too. When we got to Rod Sterling as narrator on “The Twilight Zone” we knew we had digressed too far, so we stopped then. Those of us old enough to remember “Hill Street Blues” definitely put Franz in his own category, though. For us, he remains the quintessential Police Detective. You can just imagine calls from his agent over the years. “Hey, Dennis. Remember that character you played for THAT? Would you like to play him again for THIS?”