Eric Church, The Comeback Kid

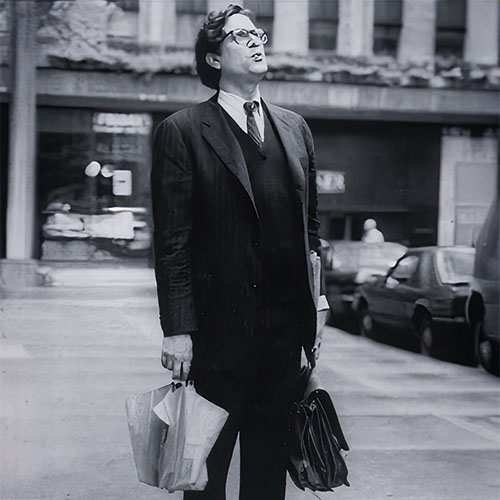

In 2006, Eric Church looked to be country’s biggest winner turned loser. His first album, the well-crafted Sinners Like Me, which addressed such topics as capital punishment, sex, and pregnancy, established him as a man worth watching. It also landed him a coveted opening spot on the Rascal Flatts tour… till his behavior bumped him into Nowheresville. He clawed his way back with 2011’s Grammy-nominated Chief, which also brought him the most nominations — five — at 2012’s Country Music Association Awards. (He won Album of the Year for Chief; the single “Springsteen” is up for two Grammys this year.)

The 35-year-old pride of Granite Falls, North Carolina, grew up the middle-class son of a furniture executive, and though he started writing songs at 13, he thought more about sports than music until college. When he finally put a band together, the six-foot-three-inch grandson of a police Chief found he liked to bend the laws a little, if not break them. And that’s part of the key to his success, even if there was some confusion at the beginning.

“My born name really is Church,” he says. “So many people thought I changed it when I first got to Nashville, since the first record was called Sinners Like Me. They were like, ‘No fuckin’ way that’s his name.’ I don’t know that I’ve ever had anybody prejudge me on that. But when we were playin’ bars and clubs, a lot of people thought that we were a church act. When they saw ‘Eric Church,’ they thought a choir was gonna show up and sing.”

“That,” he adds with a laugh, “was a little awkward.” Although he’s said he won’t be touring or recording during 2013, he has a live CD and DVD on the way, and he’s still not afraid to speak his mind, no matter that he might make waves with the heavy hitters in the country-music industry.

You’ve had an awful lot of award nods since Chief came out in 2011. How does that feel?

Somewhat surreal. Our past has been a little bit different from other artists. I came out like everybody else with our first record, and with my first song, “How ‘Bout You,” I was the “it” guy, the hit artist. And then the next single was “Two Pink Lines,” which was my choice. I thought it was a little ballsy. I’d never heard any subject matter like it on the radio, and it just didn’t do well at all. At the same time, we got fired from the [Rascal] Flatts tour, the biggest tour in country music at the time. So we got banished to the wilderness. There were a lot of places that wouldn’t even book us. People thought we were troublemakers, and we just ended up in these little bars and clubs, and sometimes not even country clubs, because they wouldn’t book us, either. So for us to go from there all the way back around to Chief, and having the No. 1 record in the world, and getting all these nominations, well, I just wasn’t sure we would ever get there. And doing it the way we did it made it that much sweeter. Because I didn’t compromise just to have success, and we were able to get that done without really having much of the so-called machine behind it. We really had to go out there and gut it out and do it ourselves.

I read that you got fired from the Flatts tour for playing too long?

That’s not all the way true. It wasn’t the right kind of thing for us. The crowd was a lot younger. I joke that we came out, and the little girls and moms sat down, and the dads stood up [laughs]. It was “guy” music, and it just didn’t fit. And basically, even though I was a new artist, I thought there should be some shared respect. We’d just come off the [Brad] Paisley tour, which was my first tour, and it was fantastic. We were treated good, and we actually got paid. Anybody in that setting has 20 minutes, sometimes 75. You’re the first of three acts. Nobody knows who you are. I’m okay with that.

But when we got the Flatts tour, it seemed to me that the better we did, the more rules there were the following night. And I couldn’t figure out how to go out there and give the show I was used to giving, and then have more blockades put up in front of us. And it kept getting worse and worse. Most artists probably would have just gone ahead and put their head down and said, “Yes, sir; no, sir.” I didn’t do that. Anytime I thought that we were getting screwed with, I would play longer. And then there would be more rules. And then I’d play longer. About midway through the tour, it started deteriorating pretty bad. I remember our last show, at Madison Square Garden. We went to do the show, and I just knew that day we were gonna get fired. My drummer wasn’t even on-stage with us. They had put him off-stage. He still jokes that he almost got to play Madison Square Garden. They’d been messin’ with us all day. I mean, just the overall organization. I never saw those guys, the Flatts. We never really interacted with each other. Anyway, I just told my guys that night, “This is probably it. I don’t know how long we’re gonna play. Y’all just follow me, and we’ll be done when we’re done.” And I think we played 40-some minutes. They started turn in’ the lights off and I just kept going. Because I thought, Well, if you’re gonna go down, you might as well go down in New York City at the Garden.

Then what happened?

The next Monday, I read a press release that we had been replaced by Taylor Swift, who was brand-new at the time. And there were still 15 or so dates that we were supposed to do with those guys, so I said, “Screw it. Let’s go play those towns.” The Flatts tour was called the Me and My Gang Tour, so we did the Me and Myself Tour. We even had a laminate printed up that just had me on it [laughs].

We went around to all these little hard-rock clubs and bars, the only places that would book us in the same town on the same night as the Flatts tour. When their show was over, we started. Some nights we had 40 people, and some nights it was packed. We had told all the fans we were coming — not that we had a lot at the time — and we came.

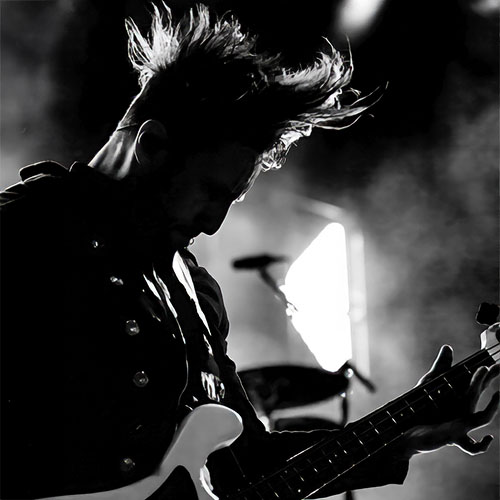

“My job is to turn that arena into a bar. Sometimes people fight. Sometimes people have sex. I’ve seen everything at these shows.”

We see Eric Church headlining arenas now, so you’re competition for real.

Well, it’s been a learning process for us. I’ve enjoyed trying to get better in that environment. Coming from the bars and clubs, my job every night is to turn that arena into a bar and a club. That’s where I’m comfortable. I think a lot of it is just continuing to offer a little bit of a rowdy environment.

I make no apologies that we’re there to party. That’s why we want our people to be there. None of you should be sitting on your asses. That’s other country shows. You should go see those guys if you want to do that. This is a “whether you remember it or not, you’re gonna feel this one in the mornin’” kind of show. Sometimes people fight. Sometimes people have sex. I’ve seen everything at these shows. The guy who does our lights is from the rock world. The first time he came to one of our shows, he was like, “I’m just blown away. I grew up with Guns N’ Roses, rock ‘n’ roll, and I’ve never seen a country crowd like that. I looked to one side and they were fightin’. I looked to the other and they were screwin’. And I saw everything in between.” So it’s been fun to see that environment that we had in bars and clubs in arenas. I’ve gotten in fights with security guys because they don’t understand I’m trying to get these people to go nuts. That’s been my biggest thing with arenas, trying to find that balance of bedlam versus a riot.

What was it that propelled Eric Church to this level? The strength of Chief?

I think it was all the things along the way. I think getting fired from Flatts helped us long-term. It was hell at the time, but it gave us an identity in a sea of new artists. At the time, honestly, we were starving to death. I had everybody on payroll, and there were so many months that we lost enormous amounts of money. All the guys got paid, but we just kept going farther and farther in the hole. It got to where we had to play seven days a week just to try to break even. And you get to a point where you’ll do just about anything. You’re listening to all these people saying, “Do this, do that,” and I was able to, somewhere in the middle of that, start finding my identity again. Going back to the beginning, we did a video for a song called “Lightning.” It was a death-penalty song. And we did “Smoke a Little Smoke,” a song blatantly about marijuana, and it was a hit on the radio. So you can back this up and find all these little things. We did 25 or 30 dates opening for Bob Seger when nobody knew who we were, and more recently, the Metallica Orion [Music] Festival, playing for that crowd. We just tried to be different, and to think more universal.

You look much hipper on the Chief cover photo than you did when you first came out.

Yeah. People had been fighting me for years on the hat and sunglasses being the image. But that’s been my look onstage for four years now, and people were coming to the shows trying to duplicate it. I got all this push back from the label, like, “Well, you have hair and eyes and you should show ‘em.” Just all bullshit.

The biggest hit off Chief is “Springsteen,” a coming-of-age song. And it also revolves around the evocative power of music. What’s the story behind that?

That song came from a real experience, from when I was around 15 or 16. You know, your first amphitheater experience with your friends, when you’re not with your parents anymore. I can remember that sense of freedom. And I remember the people around us, the guy we stole beer from, even the sky, 20 years later. And that’s really where the song came from. There’s a line in the song that talks about where melodies and memories connect with each other. That was really the ground floor of it. We just started painting pictures around it.

“I guess people figured out which room I was in. I was on the first floor, and there was a knock on the window, and a strip show of women paraded by.”

You got a note from Bruce Springsteen about it before one of your shows in New Hampshire. Was that just trippy?

Oh, man, yeah! I didn’t know what was happening. We got word earlier that day. My assistant tour manager came up and said, “Bruce’s tour manager [Wayne Le Beaux] is coming to the show tonight. He wants to say hello.” I said, “Absolutely.” They played [Boston’s] Fenway [Park] the night before. So right before the show, [Wayne] came up on the bus and was just kind of talking, and he said, “Well, I got something for you,” and he took me through the whole story of how, the night before, they’d just got offstage. They were in the car on the way to the plane, and Bruce said, “Hey, Wayne, what are you doing this weekend?” And Wayne’s like, “Well, actually, I’m going to see Eric Church.” And Bruce said, “No kidding. Hand me my briefcase.” And he took out a set list, and on the back of it, he wrote me this note about the song. And he told Wayne, “Make sure you deliver this to Eric.” [Laughs with delight] It was just bizarre.

Toby Keith is somebody you admire. Is he a role model for you?

He is. I respect the hell out of him. I admire his path. He’s somebody who really got pushed around. My favorite story of Toby’s is when he took the How Do You Like Me Now?! record to his label, he played ‘em five songs in a row. And they said, “Just shit. Terrible. Awful.” And he had the wherewithal to say, “Okay, let me buy the record from you.” And, of course, they let him, and the rest is history.

I respect having that belief, and just not letting people dictate your path. I think that happens too many times in Nashville. You kind of fall in line, and you’re supposed to do it this way, and if you don’t, the CMA is going to be pissed at you, and if you do it that way, the ACMs are gonna be mad at you, and you’re never gonna win an award, like Toby would tell you [laughs]. And there are people who just don’t fit in those boxes. I feel like Toby and myself are alike in that way. We don’t play well with others. I don’t. I’ll admit it. I don’t have a lot of friends in the industry. It’s just not who I hang with. I think some people find me prickly, maybe, but I’m really not. It’s just that I’m not going to put up a lot of false fronts or play games. I’m gonna tell you what I think about you.

You gave an interview to Rolling Stone in which you talked about the TV show The Voice. You said, “Honestly, if Blake Shelton and Cee Lo Green f-ing turn around in a red chair, you get a deal? That’s crazy. I don’t know what would make an artist do that. You’re not an artist.” That landed you in some hot water within the industry. Any regrets there?

No. Well, maybe. I shouldn’t have used names. I know some people took it personally. And it wasn’t personal. I was just trying to voice my displeasure for the system, for what has become the common way for young talent to get noticed. A lot of people said, “Well, you’re just mad ‘cause they get noticed and you had to take the long way around it.” That’s not really my point. My point was, I know what it was like to do it the other way, and I know what it meant to me. I was not ready when we first came out. I don’t know if there ever would have been a Chief record if we hadn’t been able to hone our craft and sharpen our knives. You’ve gotta find yourself a little more before the spotlight’s on you. And [shows like The Voice and American Idol] do a disservice to the artist. If they win, they think, I’ve got a record deal! Hey, I made it. And it’s only just begun. You’re just getting started. And it aggravated me that a lot of people don’t realize that this is all for TV ratings. Don’t kid yourself. It’s all for television.

So if, like Toby Keith, you are penalized at the big awards for your outspokenness, are you okay with that?

I am, yeah. Because I don’t understand how to make music to win awards. I don’t know what that gets you. I’m going to make the record I’m going to make, and if it wins awards, fantastic. If it doesn’t win awards, I’m not going to change the way I make records.

Hank Williams Jr. makes a lot of headlines with his brand of truth-telling, particularly about politics. What do you think of that approach?

[Laughs] I love it! I know Hank pretty well. He’s a really great guy, just a flamboyant, bigger-than-life personality. Country music could use more characters like him. I know the eighties wasn’t the best musical era, but I fucking loved the personalities of those hair-metal bands. And I loved what it looked like. Whether the music was good or not, you had all these characters bouncing around, and they all had this superhero thing going on. I think Hank kind of fits into one of those boxes, of somebody who’s just so unique and such an individual that sometimes he gets penalized for how he is. He’s really not like everybody else. And I personally find it refreshing.

Hank had some awfully big shoes to fill, being the son of country’s most influential legend. How has becoming a father affected Eric Church?

Well, I’m pretty reclusive. My inner circle is really, really inner. I take my family on the road with me, and that’s important to me. The father thing is obviously life-changing. I’m interested to see how it affects my music. But Katherine, my wife, was with one of the main music publishers in Nashville before we met. She’s been an integral part of my career along the way. And one of the great things about her is, she knew what she was getting into. For a lot of years there, we hardly saw each other. But she was able to be that rock, and I cling to those guys.

Did women use ingenious ways of getting your attention before you started taking your family on the road?

Oh, yeah. One particular time, I was in a hotel room in the Midwest. It was one of those days where you’ve been on the road 14 days in a row, and you’re just trying to get a nap before the show. And I guess people figured out which room I was in. I was on the first floor, and all of a sudden, there was a knock on the window, and a strip show of women paraded by. I shut the curtains and said, “That’s it. Gotta take a nap.”

Were women mysterious creatures to you before your marriage?

They’re still mysterious creatures. I don’t think marriage changes that at all. But I finally found a girl who can think like a guy. And maybe she’s made me think more like a woman. Hell, I don’t know. But it’s been good to find somebody I can banter with.

I have a sick sense of humor, and she laughs at that. And I know a lot of girls would get offended. So when you find that person who can laugh through all your really off-color remarks and jokes, she’s the one.

For (at least arguably) a sort of unsung hero — pun clearly intended — of country music, Eric Church has maintained his stature remarkably well. Along with many other things, he received nine Grammy nominations between 2012 and 2021 alone. Could be worth a look for those of us that maybe began this article with too little knowledge about an impressive performer. For what it may be worth, you can also find one of his heroes in these very pages. Toby Keith.