“I remember a time when a Negro couldn’t get his picture in a magazine unless he stole a ham or a chicken. That’s not true anymore. Without us blazin’ a trail, nothin’ might have happened.”

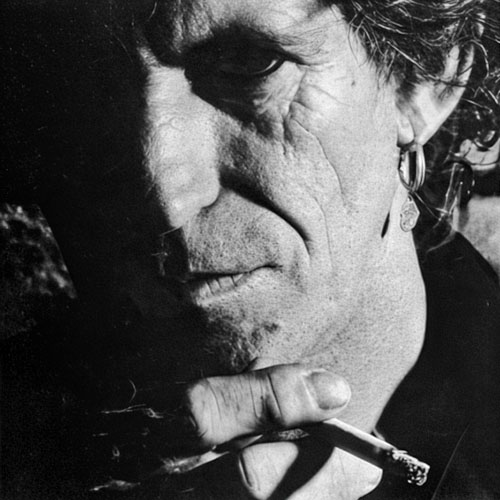

Eubie Blake

Eubie Blake was thrashing away at the keyboard when he was only six and he’s stuck with it for over eighty years — first creating the ragtime piano rage of the 1890’s, then polishing and refining it in black bars and nightclubs, vaudeville, Broadway, and speakeasies. Now he’s reviving it before standing-room-only audiences at Lincoln Center, the Newport-New York Jazz Festival, and the Boston Pops. He’s busy lecturing and jamming on college campuses and upstaging cheesecake on talk shows. Music authorities Robert Kimbell and William Bolcolm have compiled an opulent volume of interviews with Eubie Blake and his longtime lyricist, Noble Sissie, in Reminiscing With Sissie and Blake (Viking, $12.95). And a series of albums on the Eubie Blake Music label are soon to be released.

With Eubie’s comeback following the rediscovery, a few years back, of Scott Joplin’s compositions, the renaissance of ragtime is upon us. And no one is more qualified to talk about it than Eubie himself, who at ninety is as sharp as a needle and salty as a cracker and bald as an egg and as frisky on the ivories as he ever was. Probably friskier.

James Hubert Blake was born in Baltimore on Feb. 7, 1883. His mother and father were born slaves. One fateful day in 1889 he was separated from his mother in a department store. She found him playing an organ in the music department — and before they left she had arranged to buy a $75 organ for 25 cents a week.

“I wasn’t really so hot,” recalls Eubie. “Mozart was better at four.” But shortly thereafter he began playing church hymns in a ragtime that Mozart never knew, or, if he did know, paid little heed to. By the time Eubie was sixteen, he was picking up loose change playing piano in a local bawdy house. From there, he joined a medicine show, then played the saloons where ragtime was born. Eubie met many of the men who made music in America in this century and at , the end of the last. Men like Jesse Pickett — a pimp, gambler, and sometime musician who taught Eubie to perform with “dirty” guttural bass that made the lesbian whores cry out for more — and Irving Berlin, who used to listen to Eubie play in Atlantic City in 1911 and holler, “Hey Eubie! Give me my song!” That song was “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

Eubie’s first tune was “Charleston Rag,” composed in a Baltimore bar in 1889. Since then, he’s written hundreds of songs and he’s still at it. In 1921, he and Noble Sissie wrote the songs for Shuffle Along, an all-black musical, which featured “I’m Just Wild About Harry” and soon became a milestone in American musical theatrical history: it brought black artists to Broadway in unprecedented numbers and ushered in a decade of sophisticated black musicals, including Liza, Hot Chocolates, and several editions of the Blackbird revues. It was the Blackbirds of 1930 that introduced Eubie’s beautifully nostalgic Memories of You.

Eubie never stopped entertaining and was one of the most popular pianists on the World War II USO circuit. Today he lives in Brooklyn with his second wife, Marion Tyler, whom he met when she was a dancer in Shuffle Along.

In recent years, Eubie Blake has been reproached by black militants who have called him an “Uncle Tom” because some of his songs are about “mammies” and “pickaninnies,” but Eubie retorts, “I’d like to see some of these loudmouths talk the way they’re talking now if they had been tryin’ to make a livin’ in the days when the Ku Klux Klan was marchin’ down Pennsylvania Avenue, fifty thousand strong.”

Talking to Penthouse, Eubie spoke freely about his childhood, his parents, and his early days in Baltimore. Interviewer Ric Ballad made no effort to contain him, saying later, “It would have been like telling Picasso to paint a bit more neatly.”

Your best-known songs are “I’m Just Wild About Harry” and “Memories of You”—

Eubie: Well, I had five selling hits. I had nineteen hits on the stage. Like “Cravin’ For That Kind of Love.” Boy, when Florence Mills sang that, she was so great that people never heard the punch line. They jumped up, screamin’ and throwing their hats up. Then they’d go out and ask for the song — sheet music and records, you know — and they’d say, “You got that song, ‘Kiss Me’?” They had the title wrong. That happens a lot. You give a good song a title people don’t remember and it’s harder to sell.

Yes, there’s a song titled “In Other Words” but everybody calls it “Fly Me To The Moon.”

Eubie: Sure. That happens all the time.

How did you meet Noble Sissie?

Eubie: It was 1915. May the 15th. It was an event. You know, I had written a lot of numbers at that time but I didn’t have.no words to them. So when Noble was introduced to me I says, “Sissie? Sissie? That name rings a bell. Did you write a song once?” He says, “Yeah.” And I says, “Well, I’m lookin’ for a lyricist.” And we shook hands. Fifteenth of May, 1915. And we’ re still partners. He’s eighty-four years old. The first song we wrote was, now get this because it was a local hit, “It’s All Your Fault.” And Sophie Tucker sang it.

You knew Sophie well?

Eubie: Oh, yes. That’s what hurt me so bad at her funeral. Something told me to take a taxi. But I took the subway and I got there late. And they had the funeral on Seventh Avenue in New York and I was across the street and I said to the cop, “Listen mister, I wrote songs for that girl. I gotta be there. I’m Eubie Blake and this is my partner, Noble Sissie.” And the cop says, “Yeah? And I’m Booker T. Washington.” Wise guy. So he wouldn’t let us cross. And I never did get in. And they held the funeral up for me, too.

When did you and Sissie form your vaudeville act?

Eubie: Well, it happened when James Reese Europe got killed. He had a dance band that I played with. He also had a military band. Then Europe was killed in Boston, and they brought John Philip Sousa out of retirement. But Sousa had cut off his whiskers, and he cut off about a hundred and fifty thousand dollars when he did that. People didn’t know Sousa without his whiskers. They were his trademark. Listen, it’s like me, I don’t want this damned little mustache. But I can’t cut it off. Once you establish something, you gotta stick with it.

But, anyway — how I got in vaudeville. Well, when Jim Europe was killed, we had been working for millionaires — in his dance band, that is. Blue-blood millionaires. We never played for the Rockefellers or like that. We never played for the Fords, see? Because they weren’t blue bloods.

Who were the blue bloods?

Eubie: Vanderbilts, Asters, Goulds, Rhinelanders, Cabots. And we worked in tuxedos. So when Jim died, we went into vaudeville. We opened in New Haven. We played three days and then came in to the Harlem Opera House near Seventh Avenue. And then we were supposed to see these people about playing the Palace. So we get up to the sixth floor of the Palace Theater Building. Now, Pat Casey was our agent and he was one rough Irishman. A top agent. He handled Sousa, too. But how that man kept a telephone I’ll never know! God, he talked so rough. He was terrible.

So we get to the office on the sixth floor and this guy says to Pat, “Tell you what we’ll do. We get grotesque clothes for ‘em. All ragged. And we have a piano on stage, in the box. We don’t take it out of the box.”

Now, I gotta get up for a minute to show you what this man wanted us to do. He says, “Now, Sissie and Blake come on in these ragged clothes. And Blake says, ‘Hello dere! Wha’ … wha’ dat?’ And Sissie scratches his head and says, ‘I dunno wha’ dat is. Wha’ is dat?’ So then Blake inches up on the piano, lookin’ scared and he says, ‘I’m … I’m gwine touch it. Look out!’ And he hits one note and he says, ‘Why dat’s a pia-anna!’”

Now, the most ridiculous part is that he wanted me to sit down then and play the piano. That was supposed to be the joke. So Pat Casey says to him — well, I can’t say it ‘cause you’re tapin’ this. But I tell you that man cussed.

Then he says, “You want Sissie and Blake?” “Yeah.”

“Good act?”

“Yeah.”

“What did they wear when you saw them?” “Tuxedos.”

“Well,” says Pat, “if you want Sissie and Blake you’re going to take ‘em in tuxedos and they’re not going to act like that. Now, if you don’t want ‘em, I’ll sell ‘em to the Shuberts.”

And the guy yells, “Oh, no! Don’t do that!” So we went from the Harlem Opera House straight into the Palace. Now I’m not sure, but they claim no act ever went from anywhere in the sticks straight to the Palace. You had to work up to it through other big theaters. I wonder if Pat Casey is alive today? He must be a hundred and five. I ain’t read that he died.

You played piano and Noble sang?

Eubie: He sang. Oh, man, what an actor! When that guy used to sing “Pickaninny Shoes” he’d be holding a pair of imaginary baby shoes in his hand. They weren’t there, 0ut he could make you believe they were. Great actor. Of course, you can’t say “pickaninny” now.

And he’d sing, “Mammy’s Little Choc’late Cullud Child.” You can’t say “Mammy” now, either. Have to say “Mommy.”

These were all your own songs.

Eubie: Yeah, sure. We wrote our whole act. All original. When we first went on, see, all the rest of the acts except us and Bill Robinson, they all dressed grotesque. Bill wore a tuxedo or tails, of course. But all the rest did comedy.

You’ve been called an “Uncle Tom” who perpetuated black stereotypes. What about that?

Eubie: Well, now, you know I play colleges. And I tell the audiences what I’m going to do. It was right here in a New York City college where I said, “The first number will be ‘Bandanna Days.’” Oh, my! A groan went up. Four or five of ‘em don’t like it. So I said, “I knew you were gonna do that. Now I’m going to tell you, you are here today, in this university — you’re getting everything and you’re being treated like human beings. You know who are some of the people responsible for that? Miller and Lyles, and Sissie and Blake — the old vaudeville teams.” Listen, Jack Johnson was on the stage. Heavyweight champion of the world. Jack Johnson knew he had the right to marry who he wanted to marry. But this country said no. They framed him and they-sent him to prison. After that, they didn’t fire a// the other Negro entertainers. But they gave us less work.

But Miller and Lyles, and Sissie and Blake put Negroes back on the stage again. Now, if you had been a composer in those days, with songs that were hitting, what would you do? It’s so easy to talk brave about civil rights, now. It wasn’t so easy then.

I remember a time, not too many years ago, when a Negro couldn’t get his picture in a magazine like Life unless he stole a ham or a chicken. That’s not true anymore. Without us blazin’ a trail, nothin’ might have happened. I speak of Miller and Lyles and Sissie and Blake as I would of Sammy Davis, Pearl Bailey, and Joe Louis. When Joe Louis was born, he was born the heavyweight champion of the world. When Sammy Davis was born, he was born the greatest star of his generation.

I don’t quite understand.

Eubie: I mean you’re born to do certain things. Born to it. Like Jockey Lee. He was born to ride like that. Jockey Lee rode nine straight winners. He said he’d do it, and he did. He couldn’t read or write or nothin’. Happened at Latonia, Kentucky. Nine races. Kid North was his valet. Now Jockey Lee could tell time on a stop-watch but not on a straight watch. He’d say to Kid North, “What is the name of that horse in the first?” And he’d tell him. “Who’s the jockey?” And he’d tell him. “Okay. I’ll win that one. What’s the next one?”

And so on, down every horse in every one of those nine races. He called the turn. He beat Snappy Garrison in a match race, too.

Who was Snappy Garrison?

Eubie: A great jockey. Now, you know, English jockeys used to sit back, with the weight on the horse’s back. A horse drives from the back there, his power is in his hindquarters. So Jockey Lee took to ridin’ up on the shoulders. Now the horse is carrying nothing back there to hurt his drive, his momentum. But you know who first rode that way?

No.

Eubie: Todd Sloan. Before him, everybody rode

English style.

Was Todd· Sloan black?

Eubie: No! What’s the matter with you? Todd Sloan was white.

You really love horses. Do you go to the track a lot?

Eubie: Well, I used to be an exercise boy. I always liked horses. I don’t bet on them, though. You can’t beat them. You know why?

I have some ideas but I’d rather hear yours.

Eubie: You can’t beat them, because the horse can never tell you how he feels. Now a prize-fighter might say, “I can’t fight today because I’ve got the abba-dabbas and I don’t feel too good.” A horse can’t do that. Every horse in that race is a question mark. You can’t win. I go to the track for fun. You know what I do? I give my wife and our lady friend down the street one dollar each.

But you can’t bet one dollar at a track. You need two.

Eubie: You’re catching on. They got to put their dollars together to make one bet. Makes ‘em careful.

During Prohibition you played in speakeasies, owned by gangsters—

Eubie: Yeah, I worked for a place Dutch Schultz owned, up on 54th Street. But I didn’t know about him at the time. I just knew they owed me four hundred dollars. I went to the union. You know what they told me? Sue him. I says, “I don’t have to sue him. I’m paying you twenty dollars a year”— that was the dues then — “so you sue him.”

Well, I didn’t know I was working for a gangster. That’s why they didn’t want to sue him. Who wanted to fool around with Dutch Schultz? But I did get paid, finally.

That reminds me of my friend Henry Kramer, a great lyricist. He put together a show for Arnold Rothstein, a big gangster. Kramer worked for him up at a place on 57th Street. And he owed Kramer money. So I went up there with him to collect. And we’re met by this guy, he could have been a jockey, he’s so little. Dressed in a tuxedo. He talks out of the corner of his mouth:

“Who ya wanna see?”

Kramer says, “Mr. Rothstein.”

“Yeah,” says the little guy.

He ain’t even bothered to look up at us yet. He says, “What’s ya name?”

Now, Henry was fiery, so he says, “What are you askin’ so many questions for?”

And the little guy says, still not lookin’ at him, “Because it would be in your favor for me to be askin’ you the questions.”

So then Mr. Rothstein comes out. He says, “Mr. Kramer?” Just quiet and polite, you know. And he says, “You don’t have to argue with me, Mr. Kramer. I’m going to pay you everything. In fact, you should have been paid, but the man never gave it to you. How much do I owe you?” And Henry walked out with the check.

When I told a friend about Henry balling out Arnold Rothstein’s man he couldn’t believe it. Nobody could, because Rothstein, if he didn’t like you, would go to San Francisco and give a big party where everybody could see him and while he was gone you’d be found dead in an alley in New York. A perfect gentleman, though. He was later killed in a hotel.

Drugs are very big today. Were there always a lot of drugs in the music world?

Eubie: Well, in the old days, there were hop fiends. Opium, you know. We had that. Pimps were hop fiends, mainly. I don’t know nobody ever took coke or nothing’ like that. Maybe they did. I didn’t know about it.

Reaching the age of ninety is quite an achievement….

Eubie: Well, it wasn’t my doin’. I did everything that was wrong. When I was a young kid, that is. You know. Girls and everything. And I used to drink whiskey then. But I was only really drunk three times in my life. First when I was twelve years old. It was Christmas morning and my dad came downstairs and he says, “Em!” — that’s my mother — “got anything for that boy for Christmas?”

And my mother gave him one of her smart-aleck answers. She says, “Yeah, I got what you brought in.” Now, of course, he hadn’t brought in anything, ‘cause he hadn’t worked — he had carbuncles all over his arms. He always had carbuncles. You know what they are?

Like boils?

Eubie: Worse than boils. They were big, ugly red lumps with lots of heads. Terrible. He was a stevedore, you know. Anyway, that Christmas morning was the first and only time I ever see my father kiss my mother and love her. He must have kissed her lots of times. They had eleven children. But he never kissed her in front of me. I gotta tell you this. My father and mother, I loved them! I really loved them. Because he was a great old man, he was, and my mother was a Christian. I mean she was a good Christian. From the bottom of her heart. Only my mother would whip me, you know?

Now, this is Christmas morning and there’s nothing in the house. But my mother washed white people’s clothes and she carried them in a wicker basket. So my father took that basket and he says, “Now I’m going out. If I don’t come back, you just tell your friends that a man went out to get something for his family.” I loved my father before, but he got right in my heart when he said that.

So he went on out the door. And when he came back, the basket was full. A side of bacon, turkey, a loin of pork … everything. I don’t know where he got it. And he gave me a quarter. First time I ever had a quarter in my life. Now listen, I don’t make these stories up.

I know that.

Eubie: And nobody writes them for me. They’ re true. So I go out in the yard and I got some ashes from the stove and I put them in a pint bottle. Did you know that ashes make lye?

No, I didn’t.

Eubie: Well, they do. So I used those ashes to wash out the bottle and I went around the corner. There was a bar there and I went to the side door and I said, “Look. I got a quarter!” And I got a gang around me just like that. “Yeah! Mouse has a quarter.” That’s what they used to call me. Mouse.

Why did they call you that?

Eubie: Well, a guy pulled the wires down and a woman looked out and called the police and that’s how I got the name.

Wait a minute. Will you go over that again?

Eubie: Well, there was this guy named Harry Barnett. My mother said I was the worst boy on the block, but that guy! Phew! I ain’t never seen nobody as bad as that boy. He just died about five years ago. Anyway, he threw a string over some wires.

Telephone wires?

Eubie: Yeah, first telephone in our part of town. We lived in a ghetto, see? So he kept doing that until the wires came down. And, boy! Did that street light up! Like you never saw. Like lightning. So Harry ran in the house and old man Youngheimer, the policeman — a white policeman, since there weren’t any colored police-men in those days — old man Youngheimer came along and he found me standing there. My daddy always taught me, “Never run if you didn’t do anything.” So there I stood. So then this woman was in the window, and when the cop come up Harry had gone, so she pointed at me and said, “That little mouse-faced boy did it.” And that’s how I got the name, “Mouse.” So old man Youngheimer he grabbed me by the ear. That’s why I can’t hear so good today out of this left ear, because of old man Youngheimer always pulling at it like that. So he pulled me by the ear and he took me in the house and he says, “Emma!” — you know, white people in those days never called colored people “Mrs.” or “Mister” or “Miss” — so he says, “Emma, that boy pulled the wires down.”

But honest to God, I didn’t do it. Harry Barnett did it! Well, hell, he’s dead now. Hey, you got me off the track with that mouse story.

All right, so now I’m back at the saloon with my quarter and I’ve got a clean, empty pint bottle and I’m twelve years old and the gang is gathered around me. So I said, “Give me ten cents worth of Overholt whiskey.”

A whole pint for ten cents?

Eubie: Nah! A half a pint! Came right out of the barrel. And let me tell you that whiskey was maybe 115 proof! So I go up the alley and guys are saying, “Hey, give me some.” And I’m playing it big and I say, “Nah, you guys are too young. You can’t drink.” And I finished the bottle myself.

So then I come up Orleans Street and I see my father. Now my father, I never saw him drunk. Never. And he looked as tall as that church across the street. And I look at the houses and all the houses are moving. And he called to me, “Bully!”

Now that didn’t mean what it means today. I used to fight all the time so he called me Bully. That meant I was a real boy.

Bully-boy.

Eubie: Yeah. That’s it. So he says, “Hi, Bully.” And I says, “Hi, Pop.” And I fell down right in front of him. I remember falling. That’s all I remember. This was about nine o’clock in the morning. I told you how religious my mother was. They told me she prayed for me real hard.

She knew you were drunk?

Eubie: My mother? She could smell whiskey from Baltimore to Los Angeles. Well, at about eight o’clock the next morning I finally moved. And Mom hollered, “John, this boy ain’t dead! He’s alive!” Then she paused and she said, “I’m going to kill him.” Now the old man knew how she was, so he came running downstairs to keep her from — boy, she used to knock me for a loop, but then she’d always love me.

Tell us about your parents.

Eubie: My father was eighty-three when he died. My mother was seventy-eight. You know, my mother and father were once slaves. And he was in the Civil War, on the Union side. He never had a pair of leather shoes until he went into the war. And then they hurt his feet. The slaves used to wear carpet bound around their feet. The lucky ones.

I never heard my mother or father speak of their parents — my grandparents. Not once. They must have been sold when they were very little and they never knew their parents.

Did you have much trouble with white people when you were a child?

Eubie: Well, I used to have to pass two white schools to get to my school and you know how boys are. But I could hit like a mule. You see, I grew up with nothing but prize-fighters. And they showed me how to hit with either hand. I used to play the organ, so I was always sensitive about my hands. I never risked breaking them by hitting nobody in the head. But as soon as I got close, I’d hit them right in the pit of the stomach. And you hit them there and they’ve got to go. Got to go. Unless they have time to tense those muscles, nobody can take that punch and stand up. Oh, I used to fight so much. Damn! I got so sick of fightin’. I had to fight when I was playin’ marbles … going to school … going to the store … all day long.

I’d be coming home with the preacher’s daughter and I’d hear them say, “Oh, look at old Sam!” — that was short for Sambo — “look at old Sam!” And the girl got nervous. And I said, “Don’t get scared. I’ll get beat up. But the first one that comes near me, I’m going to cut him until he’s dead, dead, dead.” And I said it loud. And I just kept walking. And they didn’t do nothing. And, of course, I didn’t have no knife. I was just bluffin’ them.

Did you ever lose a fight?

Eubie: Oh yeah! One time I came in with my eyes black and my nose all bloody and busted. My father says, “What’s the matter with you, boy?” And I was cryin’ and I sobbed, “I … I don’t like white people. I don’t care what you tell me, Papa, I hate ‘em.”

And he looked at me. Boy, when my father looked that way the house, the dishes, everything rattled and shook. You never saw such a look. And he says, “Never let me hear you say that. What was done to me and what was done to your mother was done because at that time, people thought it was right.

“I know it was wrong, what those white boys did to you today. But I don’t want you to hate anybody. Now, if some guy does something to you, then you don’t have to like that one guy. That’s all right. But don’t dislike people because they’re white. And don’t hate anybody.”

He taught me that and he taught me to respect women. Females. He’d go out to work and he’d say, “Bully!” — now I’m about five years old and I had an adopted sister who was so young she was laying in a crib — and I said, “Yes, sir.” And he’d say, “I’m going out to work. Take care of these women, you hear?” Imagine that? He’s talking about that little baby that way. Callin’ her a woman. But you see, he gave me responsibility. Made me feel important. Taught me how to be a man. That’s the way I was reared. God bless him for that.

What about religion? Do you have the same kind of faith your mother had?

Eubie: No, not in everything. I’ll have to show you how rigid my mother was about religion. Sunday morning. Nine o’clock. Sunday school. Everybody else is out in the street havin’ a good time and I’m in Sunday school. Eleven thirty, preachin’ time: I’m Baptist, you see. Then two thirty, Sunday school again. In church all day Sunday, while everybody else is out having a good time. I’m in there singin’ …

Jesus knows

All about my struggle

And I’m thinkin’,

“If I ever get out of this thing I ain’t never coming back.”

That’s how you spent every single Sunday?

Eubie: Wait, there’s more. Four o’clock, along came the Baptist Preachers Union. They were there to debate, you know. Stuff like, “Which is the most destructive, water or fire?” And those guys didn’t even know what they were talkin’. Look, half of them couldn’t even read or write! You understand? And here’s what they thought:

God destroyed the world by water. The flood. The way they saw it, God had made a mistake. So next time he’s going to destroy us by fire.

And I’d sit down and think about that, and I’d say, “I don’t believe that.” And I had this boy, Fred, who lived next door to me. And I’d say, “I don’t believe that.” And he would run and tell his mother anything. So he looks at me and he says, “You don’t believe what God said?” And I said, “I don’t believe that God would kill all those people. If God is as good as they say he is, why would he kill all the people?” Well, I was a kid. What did I know? And Fred, damn, as soon as he got up he ran and told his mother. I knowed he was goin’ to do it. And this boy could fight. God, he could fight. I’ll bet he could lick Joe Louis. I knew he was going to tell his mother and she was going to reach over the fence and tell my mother and I was going to get a beatin’. But I never learned. He did it again and again.

Like, I don’t know if you ever seen a one-man band. A guy would have drumsticks tied to his elbows, and a harmonica and a cornet around his neck, and his foot worked the cymbals on a string, and he’d have a banjo, maybe. Anyway, one of these guys used to come around, preachin’. And he’d tell a story about some boys who were playin’ twenty-one, which is a card game. And he’d tell how one of the players cussed and how lightning came and hit the log they was playin’ on and set the log afire. That’s what this guy is telling the people.

Now next summer he comes around again. And he tells the same story. And I said, “You mean to tell me that log wouldn’t be burnt up in all this time since last summer? I don’t believe it.” And there sits Fred. And he says, “Oh, you’re going to die now for sure.” And he starts to get up and run to tell his mother. And I says, “You stand up and I’ll bust you in the jaw.” And he did. And I did. It was just terrible.

So you don’t believe in religion.

Eubie: No, I didn’t say that. I believe some things in the Bible and I believe in heaven and all like that. But, you see, men wrote the Bible. Now it’s like, I write a piano piece. And I give it to you and you’re supposed to make an orchestra arrangement from it. And so you see this spot and you think, “Gee, this will fit nicely in there.” But that’s in conflict with what I want, see? Well that’s the way the Bible seems to me.

Too many arrangers?

Eubie: That’s it!

But do you believe in God? Do you pray?

Eubie: Sure. Sure, I believe in God. I pray.

You started out playing professionally when you were still in your teens. Tell us about that.

Eubie: First time I played was the Fourth of July, 1901. I played for a medicine show. Of course, before that I used to sneak out of the house at night, when the family was sleepin’, and I would play at a house of ill repute. My family didn’t know. But a neighbor heard that piano sound comin’ out of the place and she says, “That sounds like Eubie’s bass hand.” And she told my folks. And I admitted what I was doin’ and I took my father upstairs and showed him where I’d stowed the ninety dollars I’d made on tips. He thought about it awhile. He made about nine dollars a week, when he worked. So he thought about it, and he decided maybe so long as I just played piano, it was all right.

But then when I was older I joined this medicine show. Dr. Frazier. He was a veterinarian. You know, most medicine-show doctors were phonies. Medical school dropouts, some of them. They put in maybe a year in school and got kicked out. They didn’t have a diploma so they had to make a livin’ somehow and they weren’t goin’ to go in the streets and do drudgery work. So they’d get up medicine shows. But my doctor was at least a real veterinarian. A real surgeon. He worked out of Fairfield, Pennsylvania, when I was with him. There was a Negro doctor there, too. He was deaf and dumb. We couldn’t talk to him.

There weren’t many Negroes lived in that part of Pennsylvania then. We was rare. We’d go down the streets and they’d call their children, “Hey, look at that. See that? You know why they’ re that way?” Then they’d tell them about how in ancient times we were turned black because of our sins. The Pharaoh and all that foolishness. And the children believed it. And the children used to try to rub off the black.

What did you do in the show?

Eubie: I played the melodeon. It was about half the size of a spinet piano. They’d pull down the tailgate and a big chain held it. That made a stage for us to play and dance on. And they had big dishpans. And the ballyhoo man would beat on them … Boom! Boom! Boom! And then the rubes would come. That’s what they called the people. Rubes. And he’d introduce Dr. Frazier. But first he would introduce us. There was five of us. Now get these names. Me, Eubie Blake; Preston Jackson, my partner; Knotty Bakeman; Yallah Nelson; and Slewfoot Nelson. I’m writing a number about Slewfoot Nelson, now.

All of us could dance and sing. But we only stayed with him a week. He’d give us breakfast and he’d give us sandwiches and we were supposed to get three dollars a week plus this room and board. I would have stayed with him but Preston was a wise guy. Talked tough. “What do you want to stay with this guy? He gives us sandwiches. We ain’t gonna eat sandwiches.”

So the man gave us fifty cents apiece and Knotty Bakeman said he was going to walk back to Baltimore from Fairfield. So he went off and I ain’t ever seen him since. That was more than seventy years ago. I wonder what ever happened to Knotty Bakeman?

Who were some of the other musicians you met while you were knocking around in the early days?

Eubie: I’ll tell you. But you may not know ‘em.

Nobody like Jelly Roll Morton?

Eubie: Well, Jelly Roll Morton, yeah. He was all right. But let me tell you, there were guys, piano players, who never ever got a chance to record anything. Great musicians. And their music is lost forever. Ever hear of Big Jimmy Green, Big Head Wilbur, Little Jimmy Green, hah? You ever hear of them?

God forgive me, I have to tell you I’m ignorant of them, Mr. Blake.

Eubie: Well, that’s all right. That’s not ignorance. How could you know about them? They never made a record. And they’re all dead now. Let me tell you something about them.

One-leg Willie Josephs. He was the greatest piano player that ever drew a breath. Had his leg cut off, I forget which one, a little below the knee. He died in 1908. His mother worked for a wealthy white family in Boston. They went to Paris and came back unexpectedly. They walk in the house and they hear this beautiful music and they wonder who’s makin’ it. And it’s little Willie playin’ their piano. They’re so impressed they send him to the Boston Conservatory. And graduation day they hold this contest, five of the top pianists playing where the judges can’t see them. And when they vote, Willie was the winner. And the man, the dean or something, he was embarrassed because he had to tell Willie, “You won, but I can’t give you the prize or I’ll lose my job.” Because Willie was colored, you see. So Willie was a concert pianist but there wasn’t any place for him to play a concert.

Willie would go around to the colored sections of town, and he’d play Mozart and Beethoven, and the Negroes didn’t want to hear that. They didn’t know anything about that. They wanted ragtime and blues and such. So Willie just gave up his music and changed his style and he became the greatest ragtime pianist ever. And then he died young, in 1908. And there ain’t no recordings nowhere of One-leg Willie Josephs.

Why aren’t there any recordings of these people?

Eubie: In those days they just didn’t think that music was worth it. They recorded some black musicians. We recorded — Sissie and Blake. The Emerson and Victor companies made race records. That’s what they called them because records of black music were kept segregated. You weren’t supposed to sell them to white people. So cooks and people who worked in white folks’ houses would sneak them on the record players and the white people would say, “Hey, that’s great. Who is that?” And they’d say, “Oh, that’s Mamie Smith,” or whoever.

What about Willie “The Lion” Smith. Wouldn’t you call him one of the great ones?

Eubie: Oh yeah, Willie was famous and he was a truly great piano player, no doubt. But Willie had a lot of braggadocio, you know. Not as bad as Hughie Wolford, though.

Hughie was my big competitor when I was young. Oh, he had a lot of braggadocio. He and Willie would hear you playin’ and they’d say, “Oh, come on, get up, get up, get out of there, stop ruinin’ the man’s music! Let somebody play who knows how to play!” They were really somethin’ in those days!

As much as being fascinating, reading interviews from fifty years ago can be sobering to the point being painful. Eubie Blake tells many a story here, Eubie died within a decade of doing this interview, but you can learn more in many places on the web. Fortunately you can find many recordings online as well as a captivating rendition of a song he wrote in 1899. So … wow.