Their self-titled debut sold three million copies, and the follow-up Awake went platinum within weeks. But the latest saviors of rock ‘n’ roll aren’t about to let success go to their heads.

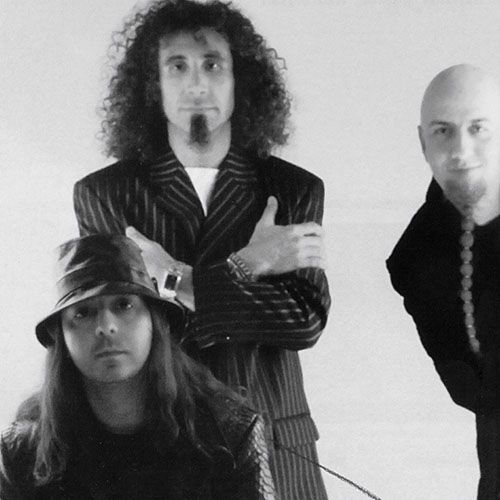

Godsmack Leaves Its Mark

“I want you to get off your ass,” barks Godsmack singer Sully Erna. “Yeah, you.” Fans spin dervishly in the mosh pits (four are churning away) while the band plays songs from its self-titled debut and its latest, Awake, but Erna is stalking the stage, aiming his rage at the more docile concertgoers sitting down. “See that mother-fucker?” he says to someone to the guy’s left. “Pull him by the back of his pants and get him up. There is no fucking sitting down at a Godsmack show. I will come out there and get you.” The guy finally stands up, and Godsmack bums through “Whatever,” the song that took the group from little-known Boston club band to among the saviors of rock ‘n’ roll.

Erna laughs a bit when asked later where his stage persona comes from. “I don’t know,” he admits. “I’m a completely different animal when I go onstage. I’m actually pretty humble in life. I mean, I’m hyper, and I have my moments where I get a wild hair across my ass and I have to go out and rip it up, but for the most part I’m kind of laid-back. I think the music takes me over when I get onstage.” He pauses, then adds, “It comes from the people. The energy we get from the audience is what drives us to do what we do onstage.”

So far, the Godsmack quartet — Erna on vocals and guitar, guitarist Tony Rombola, Robbie Merrill on bass, and drummer Tommy Stewart — has opened for Black Sabbath, toured with Ozzfest in 1999 and 2000, and performed a pre-riot set at Woodstock ‘99. Their first album sold more than three million copies, and their second sold 250,000 the first week, debuting at No. 5 on the Billboard album chart. It went platinum (selling a million copies) within weeks. The group has done its fair share of headlining dates, but it’s still all about converting the un-believers and getting the lazy members of the rock ‘n’ roll audience off their asses.

The first Godsmack seeds were sown six years ago when Erna, a former drummer, met Stewart. Erna had already run a band by the name of Strip Mind up the major-label flag-pole, but Strip Mind was dropped because, as Erna has said, “we were young and into drugs, drinking, and fighting … your typical rock-star crap.” He and Stewart hooked up with Merrill, who was working as a roofer, and guitarist Lee Richards, who left the band six months after its genesis. Rombola, who was working as a carpenter, replaced Richards.

Stewart, looking at other career opportunities, had become a certified physical trainer, but always held out hope for a future in music. “I was considering opening my own business and started doing that,” he says. “But somehow or another, I just knew in my gut that to be happy I had to play. I just had to. As much as I thought I had to start supporting myself and making a living, in other ways I didn’t really have a choice. I knew I had to play, because I’d be miserable if I didn’t.” Though Stewart was there at Godsmack’s genesis, he took some time off to move to California so he could tackle some personal issues. His return to the band in April 1998 was like coming home. “I tell people all the time that never has anything made so much sense in my life,” Stewart says.

The lads picked up their Godsmack moniker during Stewart’s sabbatical. As the story goes, the interim drummer came to practice one day with a huge cold sore on his lip. On any other day, it would have been no big thing, but they had a photo shoot scheduled. Erna not only refused to cancel the shoot, but he wouldn’t let up on the guy, accusing him of acquiring the wound by engaging in various sordid activities. The next day, when Erna walked into practice, he was sporting his own dime-size cold sore. Rombola said with a laugh, “Ah, you’ve been Godsmacked.” And while the name is also the title of an Alice in Chains song, for the band the title merely stands for instant karma.

Although Godsmack’s debut album eventually went to the top of the charts, this is not a story of overnight success. From 1995, when they first started playing together as the Scam, to 1997, when they borrowed $2,500 to record a demo, All Wound Up, the guys played just about anywhere and everywhere. Using Merrill’s cargo van, they traveled like the proverbial postal carrier — through snow, sleet, rain, and dark of night — to shows both small and large across the New England area. “There were only two chairs in the front, so we had to sit on our gear to ride to the gigs,” Stewart says. “I can remember being all bundled up, riding to shows, then unloading our equipment in the snow. It’s funny, because I look back now and say, ‘Those were really cool times.’ Because there was an essence of something about it that was really neat. Other parts of you are like, ‘Fuck, I don’t miss that shit at all.’”

Guitarist Rombola also remembers those early days. “We used to just bum around and play clubs with other bands that were playing kind of heavy stuff,” he says. “We were in there with everybody else doing it. It didn’t seem like we were any better or any worse than some of the bands — there were a lot of good bands at the time — but we just kept at it.”

“It comes from the people. The energy that we get from the audience is what drives us to do what we do onstage.”

That persistence was the key, since they might play to 35 people at Worcester State College in Massachusetts one night and then to 700 at some club in New Hampshire the next. They had trouble garnering any record-company interest based on their demo. It took one of those fluke, once-every-decade stories for Godsmack to get noticed.

A deejay at Boston’s WAAF radio station saw a copy of All Wound Up — with its cover photo of a woman bound in wire — in a pile of cast-offs. He spun the disc for fun and then started to air the songs “Keep Away” and “Now or Never.” The phones went crazy with callers who loved the tunes, and then Godsmack ottered up a new song, “Whatever.” The band was about to hop aboard the stardom express. “When I first heard that song on WAAF,” recalls Rombola, “it was the biggest … it was awesome.”

Major-label sharks hit Boston in droves, and the boys signed a deal with Universal Records. They added a couple of tracks — including “Whatever” — to All Wound Up and changed the artwork to come up with their eponymous debut, released in August 1997.

For Erna, the signing and the success of the album were part redemption, part manifest destiny. “I’m an Aquarius, so I’m a big dream chaser,” he says. “You never really think you’re going to get it. I think after so many years of toughing it out and going through the grind, you just start to believe that this is what’s in store for you. You’re only going to go so far, do well in the club scenes or playing with your friends, but you never really think of it as a national or world success. So it’s really caught us off guard, but we’re having fun with it too.”

While Erna had big dreams, Rombola was more conservative in his aspirations. “I didn’t even think we would make it,” he says. “I was kind of doing it because I love playing music and I knew these guys were good players and I liked what they were doing. It was always a dream, but I never really thought that it was going to happen. I always just figured I was playing for the moment.”

Merrill is still overwhelmed by their debut’s success. “That still blows my mind … triple platinum. Whoa. Three years ago people were throwing that record in the bucket. We were happy when we sold 100 CDs in a week.”

Booming record sales means a booming fan base, and while the band can now claim both, the guys still feel that they built up their legion of fans through endless touring and grass-roots support. To be sure, they’ve seen their share of odd crowd happenings. “I remember a kid throwing a prosthetic leg up onstage to be signed,” Erna says. “He hopped around in the mash pit for the rest of the show, and then at the end he was like, ‘Dude, can I have my leg back?’ We signed it and threw it back at him. That was very bizarre, to see someone’s leg come up onstage with the sneaker and the sock on it.”

Godsmack is also now a tremendous Internet presence. Indeed, www. godsmack.com has hosted quite a few chats with band members and fans alike. Last fall Erna hopped into a chat room only to hear that ‘N Sync’s Justin Timberlake had preceded him, much to the ire of Godsmack’s fans. “They were all fucking bashing him;’ Erna says. “I was going, ‘Wow, easy, guys. C’mon, he may be a fan of hard-rock music.’ They were just relentless. So, for whatever it’s worth, Justin, I’m sorry. Maybe Justin heard I like [his girlfriend] Britney Spears and he was trying to check out my shit.”

Britney? Wow, could there be a duet in the offing? Maybe a full-out choreography number? “Me and Britney?” Erna answers. “Oh, man, if I got together with Britney, there’d be a lot more than dance moves going on.”

“I never wanted to be the poster boy for witchcraft, but, okay, I’ve been identified, and that’s fine.”

Where other bands have gone off the deep end when faced with sudden fame and fortune, the Godsmack boys don’t admit to purchasing anything extravagant. Erna bought a house because he was tired of paying rent to someone else while he was on the road, and he bought his mother a Cadillac Seville because he didn’t want her driving around “in a rust bucket” anymore. Merrill bought things for members of his family, but nothing dramatic for himself. “It’s a little bit different for us because we’re an older band,” he says, “and we were struggling in the clubs for years and years and we know what it’s like to grind.”

The rest of the band echoes those sentiments. Stewart says, “It took us a while to get the opportunity, and we’re not about to piss it away. The only thing that’s going to stop this band is if fans don’t dig us anymore or if we somehow have a blowup internally, which I don’t imagine happening. So we definitely want to seize the opportunity we have and make the most of it.”

Erna concurs. “I don’t think any of us have gone into a rock-star ego trip,” he says, “because we’ve worked too hard at this. Maybe if we had had this success when we were 19, it could have been a little different because we weren’t mature enough to handle it. Now we’re a little bit older, so we respect the value of a dollar bill, and we appreciate and respect our fans and our families and each other.”

Erna found his calm center in the midst of a rock ‘n’ roll tempest while studying the practice of witchcraft known as Wicca. He’s loath to explain his involvement in Wicca, only because he’s told the story so many times. “I just stopped talking about that because it’s not what the band is about,” he says. “It’s my personal beliefs. They don’t ask Madonna if she’s a practicing Catholic. This is about a rock band, and that’s it. Everything else is on the side. I’ve definitely let people know what was what with that, and I wasn’t shy about talking about it.”

Indeed, during interviews promoting the band’s first album, Erna was extremely candid about his practice of witchcraft. He told Rolling Stone, “I never have a problem talking about this, because it’s something I strongly believe in. I never wanted to be the poster boy for witchcraft, but, okay, I’ve been identified, and that’s fine.”

Erna also has explained that his problem with Christianity — which he turned away from before becoming a Wiccan-stems from the fact that “they never allowed you to look into any other religions. It’s like, This is the book. This is the way. Believe it or go to hell.’ Fuck that. And who knows? I could be wrong. Maybe when I die I’ll go to purgatory and there will be Jesus going, ‘See? We tried to tell you the whole time. You fucked up, now go to hell.’”

Erna’s Wiccan revolution started some years ago when he was studying alternative spirituality. He met Wiccan high priestess Laurie Cabot — she’s featured in the video for the hit song “Voodoo” — at a pub in Salem, Massachusetts, and studied with her for a couple of years. In the most fundamental sense, Wicca focuses on how individuals are connected with nature; Wiccans study the moon, herbs, and their symbolic meanings. The spells Wiccans cast, Erna has said, are similar to a prayer a Christian might offer. In Erna’s experience, there is no connection to Satanism.

Fair enough, but it seems that any type of quest for spirituality would influence the art of songwriting. Not so, says Erna. “It has nothing to do with it. It’s black and white. The spiritual side of me is something that humbles me, centers me in life, and makes me want to be a better person. My music releases the demons.” The closest he has come to blending the two is in the song “Bad Magick” with the common Wiccan spelling. “Does it feel so bad when you’re taking a drag / and when you’re looking at the world through dying eyes?” he sings.

On Awake, the band’s second offering, which was released this past Halloween, Erna gets a chance to exorcise a number of demons. One of the first negative experiences of success the band faced — the guy who lent them the money to record All Wound Up came back and sued them, claiming a ten-percent ownership in Godsmack — gets dealt with mightily in the song “Greed.” Erna growls, “I knew when an angel whispered into my ear / You gotta get him away / Hey, little bitch! Be glad you finally walked away / or you may have not lived another day.”

Erna delves into the redemptive side of music during the closing track, “Spiral,” the theme of which he finds easy to explain. “It’s about reincarnation. It’s about why people take deja vu for deja vu. It’s about why people just ignore that, and live for the here and now. Why don’t they see the bigger picture?” In large measure, “Spiral” is an affirmation of Erna’s personal beliefs. “I believe that everyone is put into your life for a reason, and one way or another you can learn a lesson from that person,” he says. “Even if it’s some psychopathic girlfriend that [makes] you go, ‘What in the fuck was I thinking?’ Maybe you learned to live a little bit more without the blinders on.”

Many of those Erna lessons are being chronicled in the book he’s begun to pen. “I just started, for my own self. writing down stories that I remember and how I remember them;’ he says. “I decided that in a year or two or whatever, I may put out some sort of autobiography, because I’ve experienced so many amazing things that I don’t really even think people would believe. I don’t know if I would have believed it, but I’ve seen it with my own two eyes, so I know it happened.” Some of those stories are hilarious, some cruel, and some sad. “But they are just awesome,” Erna adds. “One of the first things I wrote for the introduction of the book was that I truly believe people are molded and shaped through their childhoods and upbringings. I believe that, because I think that’s what makes you the person you are today. It could be good or bad, but it still makes you that individual.

“I’ve been through every fucking thing you could ever imagine. It would take me months to tell you everything that I’ve gone through, but I can just tell you it’s been some crazy fucking shit I mean, everything from seven-hour cop chases to drugs to gang fights. Goddamn, I’ve just seen so many things. It’s amazing that I’m still here.”

Perhaps that’s why people relate to Godsmack and the lyrics Erna writes?

“I don’t even know if they know that part of me,” he declares. “I just know that I am just like them. I am a rock fan, and I can relate to them. If we’re paternal to them in some way or they look up to us, or if they just feel we can relate to them on their level, it’s because it’s both. I do give them advice, because I have knowledge to give a younger kid and I see the shit they are going through and it’s the same shit that we went through. They’re no different than us, and I want them to realize that At the same time, I’m a big kid too, so I can relate to them and fuck around with them and goof off, because I still haven’t changed in that respect I’m still someone who will sit front row at a concert”