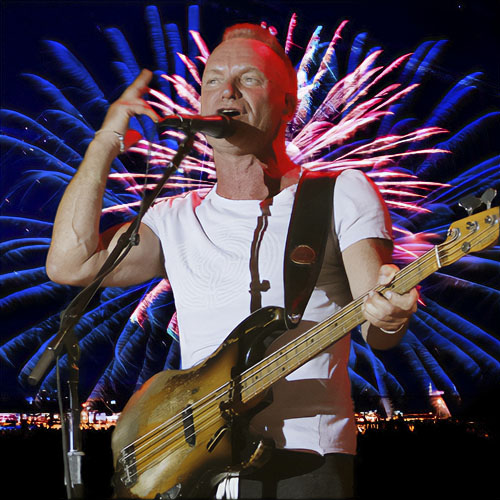

Greg Graffin, lead singer of legendary punkers Bad Religion, celebrates 30 years in music with his band’s 15th album and a memoir about his unique twin career paths.

Anarchy and Inquiry

Bad Religion frontman Greg Graffin has lived a double life for most of his adult existence. No, he’s not a CIA operative, he doesn’t have a second family squirreled away somewhere, and he’s definitely not addicted to a virtual online world, Dwight Schrute-style.

His alter ego is more surprising, interesting, and, in its own way, more punk rock: Graffin holds a doctorate in zoology, has taught at UCLA, and has been honored by Harvard University’s Secular Society for his work in science and art.

That’s right, one of the godfathers of Southern California punk is a science nerd. Got a problem with that? Bad Religion fans — or at least those who are aware of it — sure don’t: The band is celebrating its 30th year in music with its 15th album, Dissent of Man, out this month and the publication of Anarchy Evolution, Graffin’s memoir of his dual careers.

We talked with Graffin during a stop in the band’s European tour, and he told us about keeping the band together, his problem with the term “atheist,” and how Charles Darwin was a punk rocker at heart.

Tell us about the new album.

Well, as you probably know, one of Darwin’s most famous books was called The Descent of Man, so this is a play on words. And the album represents a culmination of Bad Religion’s 30 years of evolution. The sound is a little bit of a departure; we took a few chances. We even brought in a pedal-steel player, like we did on Recipe for Hate in 1993. But the strongest elements of our band have always been lyrical quality and harmonies. And those are very consistent on this record as well.

Did you imagine when you started this band at age 15 that you’d still be doing it when you were 45?

No — God, no. I didn’t even know what that meant, to be 45 [laughs]. You can’t even conceive of what it’s like to be 25 when you’re 15. I was just thinking, Let’s just get through our first record and actually play shows and build a following.

What’s been the key to keeping the band going for so long?

I always say it’s like a family — what does it mean, once you’re an adult, to have a successful family? Well, you want to be able to go back to your parents and your siblings around holiday times and not have a major catastrophe or major arguments. Being in a band is kind of the same thing. We give each other plenty of space, we’re tolerant of each other’s evolution — personal growth, that is — and we’re not too critical, or judgmental. But when we get together as a group, we take it seriously.

When I was reading your book, I kept thinking of a bumper sticker I once saw. It read, You believe in life after death. I believe I death after life. My way makes more sense.

[Laughs] I would agree with the bumper sticker. That’s great.

You don’t believe in God, but you make a point of rejecting the term “atheist ” in favor of “naturalist.” Why is atheism so abhorrent?

I think it’s because it’s nebulous. There’s nothing worse than a neighbor who comes over and tells you all the things that he’s against, without telling you what he’s for. It makes people very uneasy and I think there’s a good reason for that. It leaves you in the dark. If you say you’re not for God, but don’t say what you are for, then, to the interpreter, it opens up a world of possibilities —you could be for anything. You might as well be a baby-eater.

You write, “If Charles Darwin were alive today, I think he would find something very attractive about punk rock.” That sounds like the premise of a Charlie Kaufman flick. What did you mean?

If you consider the outrage in the community, in Darwin’s day, about what he was suggesting, it was as insulting and shocking as anything that Jello Biafra ever said in the Dead Kennedys. So that statement just suggests that it would have taken a lot of balls in those days to make [the] claim [that Darwin was making]. He was in the spirit of punk in that the shock and the outrage were due to [the fact that] the public hadn’t looked carefully or deeply enough into the phenomenon. I think that’s what makes a good, shocking punk song.

You talk about fans staking out your hotel in Brazil. The Ramones were also huge in South America-in Uruguay they were like the Beatles. What is it with South America and punk rock?

That’s true about the Ramones. I think Marky Ramone still goes down there and draws huge crowds for his solo projects. But I don’t know what it is. They’re passionate people, and they love passionate music. You know, Bad Religion and Julio Iglesias.

[Laughs] You guys have toured together, right?

We’ve played so many festivals in our lives, I’m sure we have played together, somewhere. But you know, we’re probably the only punk band that has played with Bob Dylan three times.

Have you really?

Yeah. Most recently, about three weeks ago in Bilbao, Spain.

You didn’t hang out with him at all, did you? I’ve heard he’s pretty reclusive.

He doesn’t hang out [laughs]. I’m getting to be that way, too. I’d rather go write something; I don’t really hang out much.

Should you have further interest in Mr. Greg Graffin, or, y’know Bad Religion in general, you may always visit them on this Internet Web thing. Or should you be more generally PUNK, we can help you right here.