A candid conversation with the director of Day of the Locust and Midnight Cowboy.

Exploring John Schlesinger

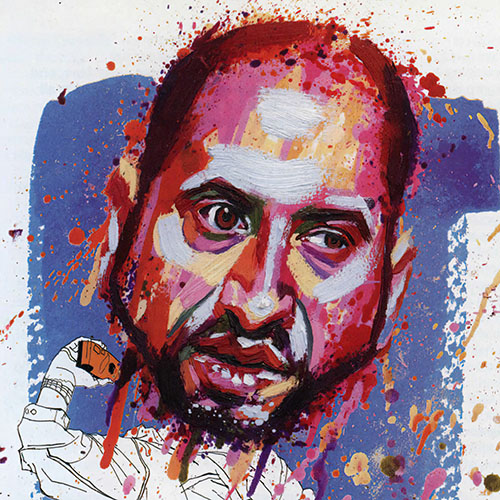

John Schlesinger is a forty-nine-year-old, balding, sharp-eyed film director, who made stars of Julie Christie and Jon Voight, who won an Oscar for Midnight Cowboy and who has now completed his most challenging film, The Day of the Locust (produced by Paramount in conjunction with Penthouse). It’s based on Nathanael West’s much-admired novel about Hollywood in the 1930’s and stars Donald Sutherland and Karen Black.

Schlesinger (pronounced with a hard “g”) doesn’t make safe movies — he makes films about life as it is, and consequently his people are as mixed up as the rest of us. A boy may love a woman and a man (Sunday, Bloody Sunday); a boy may make love to a girl and get paid for it (Midnight Cowboy); or a girl may get everything she ever wanted and regret it (Darling).

Schlesinger’s career has been full of both highs and lows. In 1963 he attracted attention with Billy Liar, which made a star of Julie Christie, and he used her again in Darling for which she won an Academy Award. In 1965 he made Far from the Madding Crowd, again with Julie and no less than three leading men — Terence Stamp, Peter Finch, and Allan Bates. “That one taught me to stay away from classics,” Schlessinger says, “at least from nineteenth-century classics.”

In 1969 he made his first picture in America, Midnight Cowboy. It won three Oscars — for best director, best screenplay, and best picture. He then returned to England to make Sunday, Bloody Sunday with Glenda Jackson and Peter Finch. It was a tremendous critical success, but the crowds stayed away. And now Schlesinger is back in America with Locust. More precisely he is back in Los Angeles, a city whose crazy quilt of wildly colored lifestyles had fascinated him when he first saw it in 1967. When he later read The Day of the Locust, he knew that Nathanael West was describing just what he himself had originally felt about the place.

Locust is a lovely layer cake with a poisonous center. It is a wild melange of aspiring starlets sucking sodas in Schwab’s Drugstore; of derelicts who used to be movie extras and who have never quite given up the dream that someday they’ll make it big; and of glittering, beautiful people who attend opulent premieres where ragged crowds of hungry Depression victims gather to cheer and adore them. This whole unreal world — as Schlesinger translates it into film-collapses and consumes itself in a movie within a movie where all realities become blurred.

John Schlesinger grew up in England at Hampstead. As a boy he was a good magician and enjoyed theatricals, but he thought that he most wanted to be an architect. He served in the British army, first as a draftsman and later as a magician in an entertainment unit.

After the war he attended Oxford, was active in dramatics, and toured America with an experimental theater group. An interest in photography led him into BBC documentaries and a Golden Lion award at the 1961 Venice Film Festival, which in turn gave him the opportunity to direct A Kind of Loving, the first of his seven pictures.

Schlesinger does considerable stage directing for the Royal Shakespeare Company in London and in Stratford, and he is also an associate director of the British National Theatre. His one excursion into musical theater was a 1973 London show about Queen Victoria called I and Albert.

Schlesinger is an unassuming man. He avoids Hollywood parties and doesn’t believe it pays to make those “easy” contacts while half-drunk. When he does attend a social gathering, he is affable and observant, drinking very little and smoking not at all. He’s a bachelor and apparently enjoys it.

This exclusive Penthouse interview was conducted in Hollywood by Ken Kelley.

How did you become a film director?

Schlesinger: Ever since I was a child I’ve been interested in the theater. Probably more than in movies. I was interested in putting on shows at home — getting out the dust sheets, rigging them I up as curtains, and putting on homemade plays with my brother and sisters. Every family occasion was celebrated with a kind of “family show.” Later, when I went into the army, I got into an entertainment unit as a magician and played in sketches and things like that. From there I went to Oxford and got interested in acting. I never really thought seriously about directing in the theater. I wanted to direct film first.

When did you start making films and where did you get the money?

Schlesinger: Back in about 1948 I made a couple of amateur 16mm films. We just sort of begged, borrowed, and…. well, not quite stole. But we got it. My family is middle class and fairly comfortably off, and my grandmother had money. She was a great encouragement to me. I used to go and say, “Hey! listen, I want some film stock,” and I would get it. I just bought the raw stock and I already had a camera. I persuaded a local wood mill to build the sets for nothing. We got costumes from some terrible tacky rental place for very little money, and people slept on the floor and borrowed caravans. Some farmer lent us a jeep and woe got black-market petrol.

The film was called Black Legend. It’s about a seventeenth-century murder and a hanging. It was enormous fun. It was just all innocence-at-large. We couldn’t afford a sound track, so we had a couple of discs — a couple of record players and synchronized music and a little bit of commentary and very few effects.

Then I left the University and became a character actor. But I also worked as a director. I made a small documentary film about Hyde Park, called Sunday in the Park. The BBC used it. Then I started doing things for a magazine-type TV program that had interviews and little films and things. And so it went.

Of all the movies you’ve directed, has Day of the Locust been the most difficult?

Schlesinger: Every movie always seems the most difficult while you’re doing it. I suppose the problem with Locust is that it’s a classic piece of writing. It’s about Hollywood — and yet not just about Hollywood. It has wonderful character observation and character writing. But one of our problems was to try and give it some kind of dramatic shape — though I’m not really very interested in plots, per se. I don’t think plots in films are really necessary, though obviously plots can help an audience.

Alfred Hitchcock once said that the best movies are made from second-rate novels because they give the director a chance to add his own creative input.

Schlesinger: But you also have less to live up to. I’m conscious that in Day of the Locust I’ve got a classic — some people don’t regard it as a major classic, but certainly a classic — to live up to. We’re going to be judged on that.

How long did you spend shooting Locust?

Schlesinger: It took us about twenty-one weeks to shoot, which is long. It was logistically tough — there were some very big sequences. And we also had some accidents; people got ill, and we were laid off for days at a time.

Didn’t some people die during the shooting?

Schlesinger: We had three people die. Betty Field died just before she was to come out here. And then Paul Hartman died after the first day’s rehearsal. It was tragic, because he’d done all the makeup tests and we’d spent a long time deciding on him. He was so thrilled at playing the old comedian, who dies in the picture. Hartman’s death was a terrible blow to us because the first week’s rehearsal, which should have been exciting and creative, was largely spent in trying to recast his part. Our set dresser died, too, but we had known that he was very sick.

How big a role did you play in the casting?

Schlesinger: The job of a director-at least in my terms — is to be concerned with everything from the very start to the final projection of the film. And fortunately with Day of the Locust, I worked with a very good partner, my friend and creative producer Jerry Hellman. He really associated himself with the project — not just always looking over my shoulder and saying, “Is that commercial?” or “Is that going to cost too much?” My criterion is always what’s best for the film, and it’s also Jerry’s. So the casting was long and involved.

I’ve always gone on the theory that casting is like chemistry, it’s a game of balance. Donald Sutherland is known for a certain kind of part from M.A.S.H. and Klute, but I don’t think anybody realizes what an absolutely incredible actor he is. He is playing a character role in Locust, which is good chemistry. I think it’s going to take the audience by surprise.

Is there any advantage in casting a brand-new actor in a leading role?

Schlesinger: Yes, like the cowboy who traveled to New York in Midnight Cowboy. People could live the experience through Jon Voight, a fresh personality and fresh face. It would have been quite wrong for us to cast a well-known actor as a hustler on Forty-second Street. It would have been far less believable.

What about Bill Atherton, whom you cast in Day of the Locust?

Schlesinger: Bill Atherton walked into our office in New York during the first week of casting. This was long before we knew whether we were really going to get the film financed and off the ground. He was immediately arresting. I saw him in the part of Tod because he was kind of raw and slightly hostile and surprising … not “actorish.” He just made me sit up and pay attention. I think he’s been absolutely the right choice. That doesn’t mean we didn’t have moments when we were all questioning things.

Day of the Locust is being compared to the old Cecil B. De Mille productions.

Schlesinger: That’s nonsense. It’s got big sequences, yes — it’s got three big sequences. But it certainly isn’t a De Mille production.

Was De Mille an influence on your career?

Schlesinger: No. The directors that I most admire are those who make very humanistic films, whether they’re flawed or not. The films of Fellini are always immensely interesting and inspiring to me, as are those of Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, Truffaut. …

Bergman?

Schlesinger: Less so. I admire his films from a distance, so to speak. I find them cold. I do think he’s an incredible filmmaker and, incidentally, a remarkable stage director in the production of Hedda Gabler he did for the National Theater in London.

A piece by critic Pauline Kael in the New Yorker said that Locust was going to be another Hollywood bloodbath, rather than the satirical statement Nathanael West intended.

Schlesinger: I take great issue with that. Obviously she hadn’t seen the film.

Why do you think she said it?

Schlesinger: I think she’s made up her mind about Locust.

Why?

Schlesinger: I don’t know why. But quite a number of people seem to have done so. Perhaps because it’s such an extraordinary film. I think it’s a miracle that we’ve been able to make it. It’s a film that’s absolutely different from anything else that’s ever been made in Hollywood. And I had the opportunity to do it without any kind of pressure from Paramount.

Did you encounter front-office interference in your previous films?

Schlesinger: Yes. Sometimes after a film’s completed, the studio will suddenly take it away from you and try and cut it. But if you fight hard enough, you get it back. It’s really a battle making any movie. It was difficult to make Midnight Cowboy … and it was difficult to make Darling.

Do you like Darling?

Schlesinger: Do I like it now? Not very much. I think it’s a little too fashionable. I think it’s too pleased with itself as a piece of moviemaking. I loved it at the time — but too much I think now. Of course, I think Julie Christie is extraordinary in it, and Dirk Bogarde is also very good. Actually, it’s a film that appealed to Americans very much more than to the English. I got crucified by the critics in England, but got the New York Critics Award here.

Was Sunday, Bloody Sunday well-received in Britain?

Schlesinger: It was well-received in London, but outside London you can forget almost any movie unless it’s really popular. I knew what I wanted to do in Bloody Sunday, and I have no regrets about it whatsoever. We knew it was risky at that time.

Chiefly because of the theme of bisexuality?

Schlesinger: Well, yes. I think it frightened many people and just didn’t interest many others. I think it was a specialized film for a certain kind of big-city audience.

It got terrific reviews ….

Schlesinger: Listen, reviews are ego trips. You’ve got to try and be bigger than the reviews, and it’s a problem sometimes. We all want to be loved, and I think in the American theater this is a disaster. They’re trying to lick it by taking big and expensive shows out on the road and saying, “Fuck the New York Times.” It’s crazy to have a play depend on one man’s opinion. Fortunately, I don’t think the New York Times can make or break a film.

Does Clive Barnes make or break plays?

Schlesinger: Well, I think Clive Barnes is able to make or break a play that opens first on Broadway. I don’t think he sets out to do it, but the position of the New York Times drama critic is just too powerful — whoever’s in it. American theater audiences have to be told what to like too much.

Tell us about making commercials for TV. Did you make many?

Schlesinger: Yes, everything from corn-flakes, “the sunshine breakfast,” to Polar Mint, “the mint with the hole.”

Do you still do commercials?

Schlesinger: As a matter of fact, yes, I do occasionally. You can earn quite good money, and you have the chance to try out new cameramen without too much anxiety. I’ve worked with a couple of good commercial cameramen who’ve later done feature films for me. Both Nick Roeg, who is a director in his own right, and Billy Williams, who shot Bloody Sunday for me … I met both of them on commercials. And Adam Hollander who shot Midnight Cowboy had done nothing but commercials. I think that was what sold him to us — a reel of commercials.

We’re not as snobbish about commercials as the American directors. If it hadn’t been for commercials I don’t think Dick Lester, who did the Beatles films and Three Musketeers, would have survived. It really kept him sane through a really bad patch. And Lindsay Anderson and Karel Reisz also do commercials.

Was finding work a problem after Sunday Bloody Sunday?

Schlesinger: Yes. I had a very bad year — the worst. We had a wonderful script in Hadrian VII — it was so much better than the play. But we started to get the thumbs-down treatment on that and I knew the year was going to be a disaster. I chose a lot of silly things, and had a rebound love affair… jumped into things I shouldn’t have.

Like what?

Schlesinger: Like a theater musical called I and Albert. It was an agonizing experience, and I know I don’t have to ever do that again. It was written by Americans and tried out in England. Actually, I think directing a musical is really a choreographer’s job. If I were doing it today, I would know what I want from it — as I think I know what I want from most things I’m working on — but of course, I’m not doing it.

You’re quite a perfectionist, aren’t you? There are many stories about the troubles you’ve had at press previews, for instance ….

Schlesinger: Well, going to the cinema today is becoming a special thing for people — like going to the theater. It’s not an everyday thing, like television. So you have to be very careful. For example, when we were showing Midnight Cowboy to the press for the first time — in a theater which I think no longer exists on Broadway — the Astor — we ran into real restrictive practices. The curtains and the lights couldn’t be controlled from the projection box, where they should be worked. There was a stagehand pulling the curtains and trying to control the lights from another area. We also found that the print looked very dark, and we subsequently discovered that this particular theater ran films at half-cock so they could save juice and therefore save money.

The only thing one can do about such things is to go on fighting and complaining. I’ve stormed out of more cinemas than restaurants — and at other people’s films, too, not just at my own. I’ve run up to projection boxes and projection managers and said, “What the fuck do you think you’re doing? I paid my three dollars and I want to see the film properly.”

Is it true that you once vacuumed a screen?

Schlesinger: Yes, at a small theater in New York. It had a really filthy screen, and nobody bothered to clean it. So I said, “If you won’t clean it, I’ll get a ladder and bucket and water and do it myself.” But I think that most directors would have done the same. For instance. Stanley Kubrick’s an incredibly knowledgeable technician and he’s an absolute demon about the style of his projection all over the world. I think the standards of film exhibition are very low. Going to the cinema in England is absolute torture.

It’s worse than here?

Schlesinger: Well, at least in America you know approximately what time a film is going to start. One of the reasons that the cinema has died in England is the way things are advertised. For instance, in my small town there is only one cinema, and the marquee simply says, “for what’s on at this theater, check your local paper.” Now, that’s no way to get people in.

But it’s not just in England. There are simply too many committees of people running Hollywood now — accountants, ex-agents. Some of them more courageous than others, but many are just frightened little men, looking backwards at what was successful.

Nobody knows what the public wants anymore. But they don’t want just escapism. I think that one of the things that has happened in the last twenty years is that people have come face to face with a different kind of truth. They don’t want something that is just a balm to apply to life. In the thirties during the Depression — that was the hey-day of the movies — people just wanted to escape. Now people are much more prepared for truth.

Do you think that bad advertising is part of the reason for the big Hollywood movie companies having undergone such a decline?

Schlesinger: Yes, as I was saying, the pop world has taken over from the movie world in terms of splendor. In the record industry, also, the standard of advertisement and cover design is incredibly high and imaginative. The cinema simply hasn’t caught up. I went to a party last week given by a well — known pop star for his manager’s birthday. One of the presents was a horse, which was brought into the restaurant, and it shat al I over the floor and was taken out again. Another present was a yacht, and a framed photograph of it-enormously blown up — was brought in, with a telegram from the shipbuilder saying, “Welcome, this is where it’s berthed.” I imagine that something like this might have happened in the old days in Hollywood. It wouldn’t happen now.

That’s part of what you deal with in Day of the Locust — in the violence of the big premiere scenes in the film.

Schlesinger: Yes, but that’s not what the premiere in Locust is really about. I think that people’s violence toward their idols exists in different strata of life. Look at the terrible violence breaking-out among spectators at football games. They like it. I mean, the people want to rip the clothes off pop stars partly because they want to get near and partly because they want to destroy. I don’t think that’s changed. If anything, it’s worse.

Then, too, the fact that television brings experience straight into the home gives people the- sense that they own whatever they see. Television is capable of bringing really incredible experiences into the home with incredible immediacy, but at the same time you have to be selective if you don’t want to be totally numbed. You don’t have to feel anything special about what you see — that is one of the great problems civilization faces. The public personality of a star becomes everybody’s property — you see them say, “Hi, Johnny” to Johnny Carson, treating him as if he were an old friend. I rather like the idea of stars going around in closed cars with tinted windows. And pop stars are certainly doing that again.

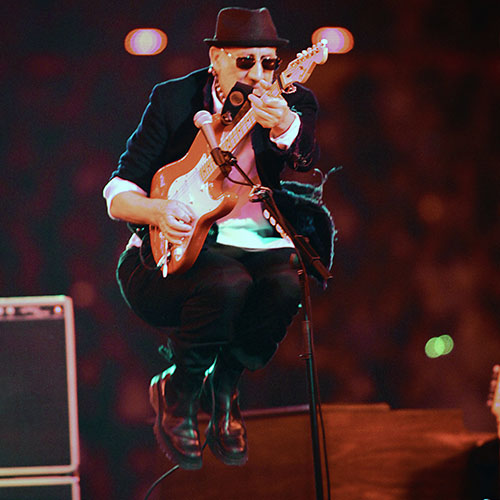

What do you think of Alice Cooper, theatrically?

Schlesinger: When I saw him, the performance was not going very well. But I think he’s a very interesting man. He wants to be an actor, and he might become a rather good one. He wants to be taken seriously.

Don’t you think he’s one of the people who’ve combined all kinds of theater and put it into a pop context?

Schlesinger: It’s a kind of Theater of the Absurd — put it that way to give it a title.

What about violence in films?

Schlesinger: I deplore violence for its own sake. I loathe the films of Sam Peckinpah, because it seems to me that they are fascistic and people ride off — even if they’ve all been killed, they ride off as ghosts — saying, “Weren’t those great days, fellows?” I hate those films!

Doesn’t Locust end with an incredibly violent, cataclysmic sequence?

Schlesinger: But it’s not gratuitous. I hope it will repel people and horrify them because, really, what the end is meant to say is, “This is where we were all heading — this is where we are all heading. That’s why I think Day of the Locust is timely.”

There are rumors that you are going to direct an opera.

Schlesinger: I’ve been asked. But I think the practicalities are very tricky. A director runs into a lot of opposition in the opera house — still, I love it because it’s a totally theatrical form. I can wallow in music and silly stories and people singing for hours on end even though they’re supposed to be dying.

What do you plan to do after you return to England?

Schlesinger: Well, first of all, I’m doing Shaw’s Heartbreak House. I’ve joined England’s National Theatre as an associate.

Would you rather direct films or plays?

Schlesinger: I doubt if you can compare them. I’m comparatively inexperienced in the theater and would like to be better at it. I think it’s a purer way of working with actors. In movies you have to get a performance straightaway. It’s like having opening night in the theater every day. In a play, you make discoveries along with the actors as you rehearse, so that what you’re doing is preparing a solid ground on which they can then give repeated performances.

At the National Theatre it will be nice to be just a part of a team. I’m not in charge — I don’t want that kind of responsibility. I’m merely a member of a group of people, most of whom can very probably direct theater better than I can. But none of them can direct films better than I.

But to get back to your question, I think that in a film a director has more control. In the theater, it’s the actors and the stage management who really control the show once you’ve opened.

Would you like to do comedy someday — perhaps something similar to Mel Brooks?

Schlesinger: I don’t think I’d be any good at slapstick. I think I’d be good at observed comedy — something much closer to life.

What do you think of pornographic movies?

Schlesinger: On the whole, pornography doesn’t turn me on. I don’t find close-ups of vaginas and cocks and assholes terribly interesting. Pornography is only interesting when you see it all in long shot with the alarm clock and the tile on the floor and all that kind of thing. Once it is analyzed, it looks like a surgical operation.

Are pornographic movies as successful in England as they are here?

Schlesinger: I don’t think the English are quite so turned on by that kind of thing. They’re much more turned on by a kind of vulgarity. In one small village I visited once, they played a game called “Going Down the River,” which consisted of singing “Going down the river on a Sunday afternoon” while a man and a woman would sit on the floor “rowing.” She’d throw up her skirts so he could peer up them. This was on a Saturday night and involved just ordinary people in an ordinary pub. Extraordinary!

I rather like all that. Drag is also very big in England. In the most ordinary working-class areas you’ll find that they often have a pub with a drag act.

Many critics have said that there are no good parts for women in films anymore. Instead, there are films like those with Robert Redford and Paul Newman — without any real female roles at all. Do you agree with them?

Schlesinger: Yes. Women have had a raw deal. In films they were kind of glamorized and idealized for a period. But now the romance has gone.

Why is that, do you think?

Schlesinger: Well, today women are saying, “We’re going to be independent — and fuck you.” And men are saying, “Fuck you, too” — which in away is basically what they were always saying. I wonder whether most people today don’t simply feel, “All right, let’s stay segregated.” But you also have to remember that historically the majority of good parts in Shakespeare, say, were for men.

Are women easier to direct?

Schlesinger: Yes, much easier-and more receptive.

Who’s been the most fun of all the women you’ve directed?

Schlesinger: Well, I’m particularly attracted, personally, to Julie Christie. And Karen Black is extraordinary to work with — highly talented. If there’s ever a lot of trouble in terms of getting a performance, it usually comes from men. I can’t quite tell you why.

What do you do when you’re not making movies or directing plays?

Schlesinger: I love lying in the sun and gardening and going to really fascinating places. I have a place I go to in the country where I grow a lot of things. And I cook — I’m a good cook. I have a partnership in a restaurant. A friend of mine and I were in school together and we started a restaurant twelve years ago. It was very successful and we built up three restaurants from it. We still own one. It’s another kind of theatrical presentation, by the way.

How do you like American food?

Schlesinger: I love it. I love Disneyland food — and there are one or two hamburger joints I also like very much. I like good food, too.

What’s the major difference you’ve found between America and Britain?

Schlesinger: One of the things I like about America is that, in a sense, everybody started from scratch. So there is a possibility and an opportunity. Of course, there’s a lot of catching up to be done for the blacks. But there’s the energy to get something done.

I think the English have a very, very serious problem — apathy and a terrible lack of energy, a terrible negative feeling. It certainly isn’t Britain’s finest hour. I think we’ve all turned in on ourselves and there is an enormous amount of resentment. It’s not so much that the “have-nots” want what the “haves” have — they simply don’t want the “haves” to have it.

I suppose one of the basic differences is that the American worker aspires to becoming a manager.

But not in England?

Schlesinger: Not at all. They don’t aspire to it. They still feel there is a kind of division, they want to have a say on the board of directors, but they don’t really want to be part of it.

Now, it’s also one of our strengths that we can be failures and not be criticized for it. Life is less competitive in England. But I don’t feel very typically English. I have much too much mixed blood.

I’m very, very fond of England. My roots are in England…. I don’t think I could possibly retire there at the moment, but that’s where I think I shall end.

Do you consider yourself political?

Schlesinger: No. I’m not political. For years I’ve been a kind of woolly-minded liberal — always finding that something one believed in has already been proved wrong. If one said, “I won’t go to Greece because of the colonels” — well then one ended up in Spain. I wouldn’t buy a certain car because it was German, and then I suddenly discover I own a German camera. Where do you draw the line?

So I’m really not political and I don’t do political things. The things I’m really interested in doing are mostly concerned with people and people’s feelings for one another. I try to make the audience go through something outside their own experience. I’ve been quoted as saying I prefer doing films about failure rather than about success — which is silly. I’m just interested in dealing with people — not with romantic heroes who don’t really exist — just plain, unglamorized people, blemishes and all. Making people actually feel in a world where feeling is at a premium is something I am committed to. Perhaps that replaces political commitment.

Full disclosure, we did not do a great deal of research on this topic, but it does not seem like there would be a pool of very many people who went from Oscar-winning film director to directing opera on the stage, but one can learn many things at IMDB. Reading between the lines, one picks up on another of John Schlesinger’s contributions to the world as well. Sadly, we may all be relegated to reading between the lines soon as “official” history has fallen victim to retelling by whatever the current Administration happens to be.