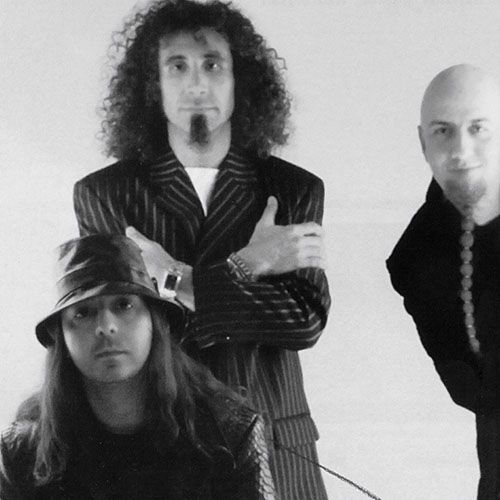

Militant onstage and enigmatic in its music, Kasabian, the most hyped British band since Oasis, is fighting its way to the top with reckless abandon — and making a few fun stops along the way.

Kasabian: You Say You Want a Revolution?

The members of Kasabian see themselves as not just a band, but a movement. Singer Tom Meighan, songwriter Sergio Pizzorno (lead guitar, keyboards), Christopher Karloff (guitar, keyboards), and Chris Edwards (bass) include in their press kit the “Kasabian Manifesto,” a rock-n-roll self-help manual that includes the following tidbits:

The Kasabian Movement is you, the fifth member.

To bring about change you need to change yourself. We believe in personal revolution…. The Kasabian Movement’s guiding aim is to change the individual.

- Do not be a passive member…. Get involved.

- Creativity is overrated, integrity is everything.

- Your time is your life. Use it. Live your desires. Live for now.

- Music is our whore…. We live music.

Those sentiments were echoed loudly by the gigantic sign above the stage at Kasabian’s debut show in New York this past November. Not exactly the old recruiting poster of Uncle Sam, the sign was a variation on the iconic Che Guevara imagery, featuring a steely-eyed masked guerrilla. Its subtle yet defiant tone apparently is meant to signify that Kasabian is looking to ignite a revolution in today’s rock scene. And they don’t want audience members to be merely spectators, but rather active participants.

If you’re rolling your eyes right now and asking yourself, “Is this for real?” then you probably haven’t heard of Kasabian before, or of the wave of momentum that the band is riding. In the band’s native Britain, the swaggering electronic rock sound (described by Kasabian as “sixties psychedelia produced by Dr. Dre”) of its smash self-titled debut has produced several hit singles. The band has toured throughout the United Kingdom and Japan, played a major British rock festival in Glastonbury, and opened for the Who. On eBay, Kasabian miscellany — from rare promo singles to concert tickets-commands top dollar.

Not since Oasis has a British band been this heavily hyped. The music press in England has been showering Kasabian with high praise, the likes of which most new bands would kill for. NME declared them “edgy, euphoric, and electrifying,” adding, “Everyone likes Kasabian.” The Daily Star gushed that the group is “the best thing to happen to British music in ten years.” And the guys themselves have the guts to say, “We’re the best band in Britain.”

Still, they were surprised by the extent of their good fortune. “We were stunned,” says Meighan, the cheerful and cocky singer. “We had hits that touched people. When you put a single out, you’ve got to be able to connect with people. We were always confident, but I suppose we were shocked a little bit because it was happening to us.”

Now the band is looking to make a name for itself in America with the release of Kasabian (RCA). Their first taste of America came last fall when they performed at New York City’s Bowery Ballroom. Living up to their guerrilla reputation, they played a blistering, explosive set that combined the atmosphere of a punk show with that of a hazy, drug-induced rave. If RCA had had any worries about whether Americans would be hip to Kasabian’s acid-house grooves, they must have quickly vanished when the crowd started jumping around and pumping fists in the air.

“We toured in the U.K. for eight months. Then we went to Japan and you realize, Shit! We’re quite big out there as well. That was so unbelievable, that someone 8,000 miles away is buying the album and coming to your gigs.”

That buzz and excitement had left the band members slightly exhausted the next day, when Penthouse caught up with Pizzorno and Edwards. The duo, dressed in hip grungy attire, looked like the stereotypical young musicians who haunt Manhattan’s Lower East Side. (Meighan and Karloff were not available at the time; Meighan was interviewed later.) They were, for the most part, mellow, polite, and articulate. Still, they couldn’t resist a few off-the-cuff remarks, like this exchange:

Pizzorno [passionately]: “We’re in a band making music. What more can you want?”

Edwards [jokingly]: “I want to meet the queen.”

Pizzorno [scornfully]: “Hang the queen! Fucking royal family! Don’t get me started on that. If you believe in the royal family, then you are delusional.”

The band was thrilled with the successful New York appearance, an encouraging sign of things to come. Meighan says, “We went to New York not knowing what to expect. We got everyone in the Bowery Ballroom dancing on their feet. For a British band that no one knows about, that wasn’t bad, man.”

But they also admit it’s too early to predict the wider overall American reaction to their music, especially compared with the massive popularity they’ve found in the U.K. and Japan. “I don’t think we really can answer that yet,” says Edwards. “Because last night it was 50 percent industry and 50 percent fans. We get a good response in the U.K. Definitely the Japanese fans are totally twisted. Not in a bad way, but just fucking mental, which is great!”

Pizzorno adds, “You’re gonna get chin scratchers because they’re always the cool ones. New York is the coolest city ever. We’re all very similar, man. I noticed that traveling the world. We’re not that different.”

As far as they’re concerned, they’re fighting their way to the top with reckless abandon (and making a few fun stops along the way). Militant onstage and enigmatic in their music, they couldn’t have picked a better representation of who and what they are than that illustration of a masked guerrilla at their concert. “It’s just a logo,” says Edwards.

“It’s a guy on the street having his own little revolution,” adds Pizzorno.

Kasabian has been compared to early-nineties British rock bands Primal Scream, the Happy Mondays, and the Stone Roses for their petrol-driven rock, electronic textures and funk grooves, and psychedelic, acid-induced lyrics. Although flattered by such comparisons, Meighan likes to think they’re forging their own sound. “We’re not copying their records,” he says. “I think people are just trying to pigeonhole us.”

“It’s a compliment, but we’re ourselves,” adds Pizzorno. “We were influenced by the same people they were influenced by. I respect those bands, but we’re not Primal Scream or the Stone Roses. We share the same attitude — that we don’t give a fuck.”

That fierce, independent working-class spirit had its humble beginnings a few years ago when Kasabian formed in Leicester, a small city in the middle of Great Britain. Its previous musical export was pop crooner Engelbert Humperdinck, not exactly a favorite son in Meighan’s eyes. “That foul old bastard!” he says. “What a waste of time he was!” But Meighan has kind words for the town’s working-class aesthetic. “It keeps you leveled. No matter where we go in the world, we still love Leicester. There’s no place like home.”

The guys were already friends before they started the band in their late teens. “We’ve known each other from different times, like from high school, really,” says Edwards. “We all kind of became friends from there. Sergio knew Tom from going down to football games. It just all came together. We just started pissing about [when we were] 16.”

“None of us wanted to work,” adds Pizzorno. “When Oasis came around, that’s when I decided to play guitar and make music for a living.”

Meighan joined at the invite of Pizzorno and Edwards. He’d had a reputation for singing on the street for fun. “I used to get a little drunk,” Meighan remembers, “and I came out shouting and singing things. Everybody was fucking loving it. It was quite cool.

“The first time I joined Serge’s band, I was telling everyone, ‘We are going to be the biggest band in Britain one day,’” Meighan continues. “That’s how cocky we were. [Music] wasn’t a hobby for us. We just did it because we loved it.”

Kasabian’s music draws on a variety of influences, aside from the obvious. Asked what music he listened to growing up, Edwards shrugs and says, “Everything from classical to hip-hop. Anything, you know, just a wide array of music.”

Meighan was raised on Motown, which would prove crucial to the band’s sound. “I’ve been wanting to sing since I was three,” he says of his early exposure to soul music.

“Growing up, man, I was lucky my dad was into the Stones,” Pizzorno says. “I learned a lot of blues from the Stones. I’m into Can at the moment, and recently Jim O’Rourke and Neil Young as well. I’ve been getting into that heartfelt country stuff. That’s sort of fucking getting inside my head at the moment.”

The reference to the Rolling Stones is interesting because Pizzorno, with his brooding good looks and charismatic yet casual manner, is reminiscent of a young Keith Richards. He enjoys the trappings of the rock-n-roll lifestyle, saying, “It’s a big sweetshop, man. You can eat and taste as much as you like. It’s just knowing when to stop and what’s real. It’s everything you ever wanted.” But he still believes, as do the rest of the band members, that the music comes first. “It’s as simple as that,” he says. “All we want to do is [make music that inspires people]. Because I’m allowed to play a guitar. That’s what I do. We all just fucking bang instruments. If you ever forget that, that’s the day you die.”

Meighan calls the band’s music “ectoplasm rock,” referencing the movie Ghostbusters. “You’re not supposed to cross rock-n-roll. But we crossed it with dance and funk, and we crossed the streams like the Ghostbusters. So it’s ectoplasm rock-n-roll.”

The guys named the band after Linda Kasabian, the getaway driver for the Charles Manson Family members responsible for the grisly murders of Sharon Tate and others in 1969. Pizzorno says, “The reason is, we liked the name, not because it has anything to do with Charles Manson.”

“We’re just kids, man. We’re just children. We just lose control, the pair of us. No one has any idea what we do onstage. It’s almost like you get everything out of your system and then you carry on with it.”

The band’s beginnings were grass-roots — literally. Rather than a state-of-the-art recording studio in London or even in a garage, they rehearsed and then recorded their CD at a farmhouse in Rutland, 30 miles from Leicester. “This deejay [friend] invited us to a party at a farm,” remembers Pizzorno. “It was a fucking amazing place. We didn’t want to move to London, so we asked the landlord if we could rent his house for a while.”

The farm, once a textile mill, is surrounded by several abandoned industrial buildings. Kasabian created a rehearsal and recording space with modern conveniences, including a sound system, a computer, a PlayStation, and a TV, all of which seem at odds with the idyllic, sprawling countryside. But the idea of creating music at an isolated farmhouse was appealing, Pizzorno says, “just because it was fucking lunacy to come live on a farm in the middle of nowhere and make music. It’s something that rock-n-roll bands should do, I think. Why not?”

Kasabian also threw parties for friends and staged a mini-festival where people set up tents to watch the band play in one of the abandoned buildings. “We lived like hippies for about two years,” says Meighan. “With our hair grown long, lots of facial hair, and lots of cigarettes. It was unbelievable. When we’d go out to town, people would look at us and go, ‘Ugh!’ You’d go home and your parents would go, ‘Look at you, you scruffy shit.’ It was an amazing time.”

Kasabian departed the farm only recently. As Edwards tells it, “We were getting a little too big for the place with respect to the people who live there. We had a lot of people come over, and it got a little bit too mental.”

One surprising thing about the band’s debut CD is that they produced it themselves, something almost unheard of for a new band, which they say was born out of necessity rather than ego. “We tried a few [producers] and it just didn’t work,” says Pizzorno. “We’re very much our own people, who know exactly what we want.”

Their cut-and-paste approach to music-making incorporates a number of electronic flourishes. Their song “1.0.” features a whirlpool of computerized crackles and bleeps reminiscent of early Roxy Music-era Brian Eno; the layers of synthesizer atmospherics on a few other numbers recall David Bowie’s Eno-produced Berlin trilogy of the seventies. Pizzorno is happy with the results, although those sonic touches came after many late nights behind the computer. “Those big sounds, those sweeping sort of noises, it’s just a trip, man,” he says. “It’s pleasing. Doesn’t matter where it’s from as long as you like it. It’s just music. Don’t be frightened. Just do what you want to do.” But even without the synths and computers, the band can play straightforward, danceable rock, as on the rousing “Club Foot,” “Reason Is Treason,” and “Test Transmission.”

Kasabian’s sound is also marked by pronounced soul and hip-hop influences, as on “L.S.F. (Lost Souls Forever)” and the single “Cutt Off,” delivered by Meighan’s soulful vocals, which pay homage to both the Animals’ Eric Burdon and American rappers. During the New York show, the group dedicated the funky “Processed Beats” to the late 01’ Dirty Bastard of the Wu-Tang Clan. “Bands forget that groove is an important thing to have,” Pizzorno says. “Nothing is better for me to have than a fucking beat. I like to hear a groove.”

Pizzorno’s noirish, imaginative, and enigmatic lyrics take a page from pulp fiction, with visions of a dark, sinister world populated by down-and-out characters, urban decay, and psychological drama. “Most of the songs were written on those subjects: war and peace, love and hate,” he says. “A lot of it is like from a movie. They’re not about personal things that I’ve experienced. It’s almost like writing a script and then putting it to music. I was just writing shit down I was noticing on the telly, or something someone would say. They’re really not about certain subjects.”

A demo tape of “Processed Beats” made the rounds until RC A Records signed the band in 2002. It was a sweet victory for the group, which a few years earlier couldn’t get noticed. “Nobody gave a shit about our band,” Meighan says. “But we kept going and going and going to get ourselves a deal so we could expand our music to people. And we came up with this funky bass line and big beat [on “Processed Beats”], and it was like, ‘Yeah.’ And they signed us.”

Live, their sound is punchier and more anarchistic than on the CD, with the synths and computers taking a backseat. “It’s a different thing, and it should be,” says Pizzorno. “If you want to sound like your CD, then stay home and listen to it. There were 600 people [at the New York show] last night. And that’s a totally different environment to listen to fucking music. It’s a celebration, it’s a gig, man, it’s a night out, and you got to give everything you got on that stage. Live — it’s bang!”

“The records are very organic and psychedelic, but we Just step it up a level live. People want to be fully thrilled and go mad for that hour and a half. That’s what people need, and that’s what we’re giving them.”

“The records are very organic and psychedelic,” says Meighan, “but we just step it up a level live. People want to be fully thrilled and go mad for that hour and a half. That’s what people need, and that’s what we’re giving them.”

When it comes to performing, the two main focal points are Pizzorno, with his aggressive guitar playing, and Meighan moving and grooving like a rapper. Band chemistry can be fueled by creative and personal friction within the ranks, although Pizzorno dismisses any notion of a battle for face time between him and Meighan. “We’re just kids, man,” he says. “We’re just children. We just lose control, the pair of us. No one has any idea what we do onstage. It’s almost like you get everything out of your system and then you carry on with it.”

Asked if proclaiming themselves the best band in Britain makes them arrogant, Pizzorno quickly responds, “I think believing in yourself is healthy. We’re not arrogant. Arrogant people are horrible. Self-belief is what we should all have.” As for Meighan, he says with a laugh, “We’re not nasty boys, we’re nice boys.” The thoughtful and reserved Edwards, meanwhile, says, “There’s a fine line between confidence and arrogance. I think we’re a bit on top of the confidence scale.”

The band has so much confidence that they’re indifferent to criticism and have the hubris to call out other bands. They’ve already engaged in a war of words with the Darkness, another hot British group. “Darkness, they’re a joke, man,” said Christopher Karloff on the BBC’s Website, “and everyone who thinks differently, they’re a ****.” Is this the making of a rivalry like Oasis versus Blur in the nineties? “There’s not a rivalry here,” says Pizzorno. “Guys should get a new wig and fuck off! So what? They ain’t worth dissing.”

Meighan concurs: “I don’t think the Darkness cares, because they’re too busy in their circus tent and we’re too busy making rock-n-roll music.”

They see themselves as the only band that can reinvigorate the British music scene. In the record-company press release, Meighan claims quite passionately, “British music needs a kick up the arse.” He elaborates to Penthouse, saying, “Britain needs a people’s band to believe in, and we’re a people’s band. Just for people to connect with us. Everyone looks at us and says we’re famous, but we never meant to be.”

Pizzorno couldn’t agree more. “It’s not about killing the competition, it’s competing,” he says. “We don’t kill other bands. We just need someone to compete with. At the moment, we’re the only ones.”

“It’s not [that] there’s no good bands out there,” adds Edwards. “It’s just that no one is sticking out.”

So far, Kasabian is standing out all on its own, winning admiration from fans, including singer Liam Gallagher, of Oasis, and the Who’s Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey. In fact, the latter invited Kasabian to open one of their U.K. shows. “We got a phone call, and they were like, ‘Do you want to do it?’” Edwards remembers giddily. “They didn’t even need to call us!”

Their most recent high-profile appearance was at the Glastonbury rock festival, where they played to thousands. “We used to joke about it at rehearsal,” says Pizzorno. “It was Sunday morning, and I was fucking hung over. Tom walked in [cheering], ‘Glastonbury, come on!’ I remember the moment he said it, I shivered. I had dreamed about playing that fucking thing, and then we did it in front of 20,000 people. It was crazy.”

“It’s an achievement,” says Meighan, who considers it career-defining. “From that day on, I knew our lives were going to change forever.”

Kasabian has its share of rabid fans.

“You get fans that follow you around and stuff,” says Edwards, “and you get weird fans as well. You see people sneaking into your shows and pretending they’re working for you.”

Meighan recalls one incident when he was hit below the belt, so to speak. “These two girls were undoing my fucking jeans!” he recalls. “They were like, ‘C’mon! C’mon!’ I was like, ‘What the fuck? I have to get on the [tour] bus.’ They wouldn’t let me go. Our tour manager pulled me by the neck, and we got out of there.”

They hope to achieve a similar, albeit tolerable, level of fame in America, a task they admit is a massive challenge. “There’s something about [America],” says Pizzorno. “When you are a fan from Britain, there’s something about seeing some of the old footage of the Beatles and Stones coming here and taking over that’s kind of nice. There’s somewhere inside of you that says, ‘My God, I’ve got to crack [that market]!’”

Says Meighan, “I think we’re the band that can do it. I really believe it. We’re on fire. Why not? All we could do is come over there, do our thing, and that’s it.”

As one might expect from this relatively recent — well, in Penthouse Legacy terms — article, one has many options for finding Kasabian online. In addition to the standard (for that era) facebook page, they of course have the site formerly known as twitter, YouTube (yay), and even their own website — which does link to YouTube a lot, diminishing its excellent work not even a little. The store even sells vinyl records too, which we find wonderful (because some of us are old like that).