Last October, World Boxing Council heavyweight boxing champion Larry Holmes ended Muhammad Ali’s attempt at a comeback and sent him into retirement when he totally outclassed Ali in a bout that was stopped after ten rounds.

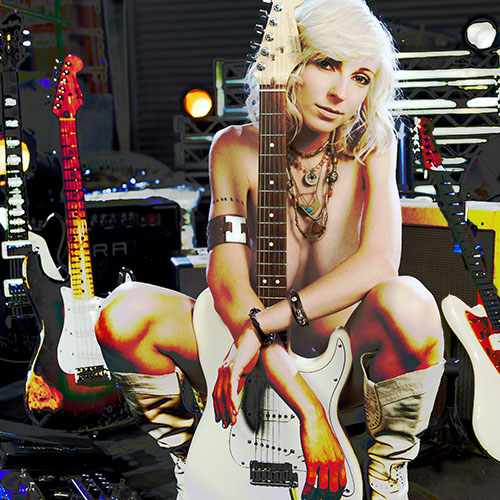

Larry Holmes

Holmes reportedly earned $6.5 million for his night’s work, but the victory wasn’t without its bittersweet aspects. Ali had long been his ring idol as well as his benefactor. Holmes’s initial earnings as a boxer came in 1971, when Ali hired him as a sparring partner. By now, it seems possible that Ali’s student eventually might make people forget all about the master himself.

Undefeated in 37 pro bouts, Holmes is a superb stylist who’s equally adept at offense and defense. The 31-year-old resident of Easton, Pa., possesses the most damaging left hand in boxing today, and he uses it like a battering ram. He is perhaps the only fighter in the world who can deck an opponent with a single left jab. Still, Holmes generally isn’t regarded as a devastating puncher, even though the Ali fight was his eighth straight title defense to end in a knockout, thereby tying the divisional record established by heavyweight Tommy Burns in 1908. Since winning the World Boxing Council crown from Ken Norton three years ago, Holmes has become boxing’s most dominant titleholder, and at the moment there’s not a single heavyweight on the horizon who seems even remotely capable of defeating him. Holmes won’t go begging for challengers, however, for these days the WBC heavyweight championship automatically makes its holder a multimillionaire. The Ali bout was Holmes’s biggest fistic payday, but the so-called Easton Assassin has been hauling in seven-figure purses since winning the title in ’78. Holmes received $1.5 million for defeating lightly regarded Ossie Ocasio in his second title de: tense, and his bout with Earnie Shavers in ’79 brought him $2.5 million. For a young man who was so poor that he couldn’t afford shoes at the start of the seventies, Larry Holmes has clearly come a long, long way.

Born in Cuthbert, Ga., on November 3, 1949, Holmes was the fourth eldest of John and Flossie Holmes’s dozen children. The family moved to Easton when Holmes was five, but his father couldn’t find work there and moved on to Connecticut, where he labored as a gardener and sent money home. It wasn’t enough to keep the family off welfare, and when Holmes was 13, he dropped out of the seventh grade to work full-time at a local car wash for a dollar an hour. It was the first in a string of low-paying pursuits that included sandblasting, working in a quarry, pouring steel, and driving a dump truck.

When he was 15, Holmes and his friends would show up on Saturday nights at local bars, where they fought each other in exchange for free meals. Holmes became an amateur boxer when he was 19 and won 22 of 23 fights before turning professional in 1973. He then ran off 21 straight victories but remained unknown and unrated until he defeated Roy Williams in 1976. It was a costly triumph: Holmes broke his right thumb in the bout and didn’t fight again for nine months. When he got back into action in 1977, Holmes easily dispatched four opponents. He finally got a big break in 1978, when he was matched against the powerful Shavers. Holmes gave the veteran contender a boxing lesson in the course of easily outpointing him, and three months later Holmes won the WBC title in a grueling 15-round bout with Ken Norton. Until April, when he won an easy 15-round decision over tough Canadian heavyweight Trevor Berbick, Holmes had knocked out every opponent he’d faced since winning the title.

To interview Holmes, Penthouse sent free-lance writer Lawrence Linderman to meet with the heavyweight king in Easton, Pa. Linderman reports: “Larry Holmes is currently one of the sporting world’s hottest commodities, and getting him to sit down for an interview isn’t easy. Since defeating Ali, Holmes has been constantly on the road to attend various sports and charity functions, and although we began our interview in Easton, we ended it in New York, just before Larry was about to board a plane for New Orleans.’

Holmes is six feet four inches tall, weighs two hundred fifteen pounds, and indeed looks like a boxer. When I met him at his office in downtown Easton (yes, there is a downtown Easton), Holmes shook hands the way most fighters do: gently, the better to protect those valuable mitts.

Holmes schedules his time carefully and wanted to get on with our interview immediately, but between unceasing phone calls and visitors to his office we got very little accomplished. We began our interview the next morning, when I met Holmes at his huge house, which he shares with his wife, Diane, and one-year-old daughter, Kandy. Holmes helped design the cavernous place, and it includes such amenities as a gym and a large indoor swimming pool. The feature Larry likes best is that the house was fully paid for before he moved in.

The heavyweight champion is a friendly, intelligent man who finds that his goals keep changing. A few years ago all he wanted was to become heavyweight champion of the world, but now he’s become preoccupied with preparing for a life outside the ring. Holmes takes as many speaking engagements as he can in hopes of one day being glib enough to become a television fight commentator. (‘Can’t you see me and Howard Cosell as a team?’ he joked, when telling me about his plans.) Regardless of how that pans out, Holmes has no intention of becoming another ex-jock on the New York-Los Angeles circuit; he intends to remain in Easton, Pa.

“Although Holmes had begun preparations for his June title defense against Leon Spinks, the Ali fight was still on his mind, and it provided the opening subject for our interview.”

Before your bout with Muhammad Ali last fall, you said you admired him so much that you really didn’t want to fight him, but you also said you wanted to “get the monkey” off your back. Exactly what did you mean by that?

Holmes: I meant that people were uncertain that I could beat him. Ever since I won the title, people were telling me, “Ali’s gonna knock you out. He’s the real champ, and he can still beat you.” That was the monkey I wanted off my back, and it’s gone now, but I also knew there was no way I could really win. I mean, no matter how good I did, people were still gonna say, “Well, Ali was old when you got him.” And that’s happened to a certain extent, but I don’t pay those people no mind.

Nevertheless, most boxing experts feel it. WJiS obvious that Ali was well over the hill when he fought you. You don’t think so?

Holmes: Oh, I didn’t think he was well over the hill, but I didn’t think he was the way he used to be, either. Ali tried to convince himself that he was as good as most people thought he still was, but I knew that wasn’t true after watching his second fight with Leon Spinks, which Ali won on a close decision. That was almost three years ago, and you don’t get any better with age, not when you’re as old as Ali and have fought as many times as he has. You can only get worse. So when we signed the contracts for our fight, I knew I could whip him-and he knew it. I just couldn’t see him beating me. A lot of other people thought he could, though, and as a matter of fact they made Ali believe he’d win. But that’s the fight game.

What had you seen during the Ali-Spinks fight that made you so confident about putting him away?

Holmes: I thought Ali was vulnerable to body punches, especially right hooks. And he never could block a jab without pulling away from it, and the same thing was true about Ali trying to block a right hand. He used to have such good reflexes that he could pull away from those punches, but when he couldn’t, he’d get hit. Those were the main things I saw when I looked at the Ali-Spinks fight, and when we fought, Ali tried to pull away from all the jabs that I threw; he didn’t try to block them. Well, he couldn’t pull away or duck under them, because his reflexes weren’t as fast as they used to be., Somebody for ABC television counted the number of jabs I threw in the first round, and out of 69 punches I’m supposed to have landed 56.

Going into that fight, Ali knew he’d have to defend against your jab. What did you have to watch out for?

Holmes: His overhand right, which I knew Ali would try to throw over my jab. And he did come over it a couple of times, but nothing serious. The big improvement that I saw in myself during that fight was that I think better inside a ring than I used to. Just about every time Ali was ready to do something, I knew what he was going to do before he could try it. For instance, when he’d get ready to throw a jab, I’d throw a jab and beat him to it. And every time he was ready to throw a right hand, I moved away from his right, so he couldn’t throw it. Ali’s problem was that he couldn’t get off, and he couldn’t get off because I didn’t let him get off. Three years ago I don’t know that I could’ve thought that quick.

Ali was always a master at psyching out his opponents. Did any of his shenanigans before the fight irritate you?

Holmes: That stuff might have worked on some other fighters, but no, it didn’t get to me. Before the first round started, he was out there getting the crowd to yell “Ali! Ali!” but I knew this much about it: you can have 100,000 people cheering for you, but they can’t help you fight. He didn’t bother me at all.

A lot of people thought you were doing some psyching on your own when you made him wait in the ring for more than five minutes before emerging from your dressing room. Was that deliberate?

Holmes: No, it’s just that the schedule was messed up. Really, I had no intention of making him wait. There was so much excitement that night it almost seemed like amateurs were running the show. There was just no control, and when I found out that the fight wasn’t gonna start on time, I raised sin about it.

If you noticed, when I finally got into the ring I did a lot of moving around, trying to keep warm. See, once my body’s ready, I want that fight to start; I don’t want to stand around listenin’ to a whole lot of jive. In the dressing room, I loosen up, shadow-box, do my bends, and I break a nice sweat. At that point, I’m ready to fight. I get myself to a peak, and if there’s a delay, I lose concentration; my mind starts wandering, and then I have to build myself back up again. There was just no control that night, so I had to do what I thought was right for Larry Holmes. Ali could have stayed in his dressing room the same as I did in mine.

You used to be Ali’s sparring partner. Do you think that gave you any kind of edge in the fight?

Holmes: All it gave me was a job, but back then just being a sparring partner for Ali was something I never thought I could do. In 1971, when I was ·still an amateur, my former manager took me up there and I was hired as a part-time sparring partner. I felt like I was working for the king. News travels pretty fast in boxing circles when you have potential, and it wasn’t long before people heard the rumor that I fought similar to Ali, so before the second Ali-Joe Frazier fight, Joe hired me as a sparring partner. I learned a lot about boxing from those guys. But even more than that, being around Ali and Frazier taught me a great deal about life in general. Joe was a local guy in Philadelphia, but I traveled to a bunch of places with Ali, and he showed me what people expect from you, not just as a fighter but as a person. In and out of the ring, Muhammad Ali was always a champion. I mean, even when he was in a down mood, he always treated people with respect and had a smile for them. Other fighters would say, “Get out of here. I ain’t got time for you.” But Ali was always a gentleman. I respect him and like him a lot.

Do you remember how you felt the first time you got into a ring with Ali?

Holmes: Yes, I do. I wanted to make an impression and show Ali I was worthy to be a sparring partner. And when I sparred with him — in ’71 and as late as ’75 — Ali worked good. People now say that Ali doesn’t really box or hit back when he spars, but he hit back when I sparred with him. Later on, he started working with smaller sparring partners, and before our fight, well, I think he just didn’t train with top-notch boxers. He trained with Marty Monroe, which was a good move — Marty’s a pretty good fighter-but he also trained with lighter guys, because he thought it would make him faster. But those guys couldn’t really put pressure on Ali or make him back up, which he was gonna have to deal with when he faced me.

On top of that, I don’t think Ali really worked out on them, which was another mistake. My theory about training is that the only way you can get in shape is by throwing punches; you can’t get in shape only by running up and down hills. That’s something you’ve got to do for sure, because stamina is a boxer’s top need-you can be the best damn fighter in the world, but if you get tired in the ring, a kid can whip your ass. Muhammad Ali always had a lot of stamina, which is one of the best defenses in boxing. Ali also had a lot of boxing ability and very quick hands, but no real punch. That was enough, though.

After the fight, Ali claimed that the thyroid pills he’d taken to lose weight had slowed him up and were responsible for his lackluster performance. Do you believe it?

Holmes: Hell, no. Ali said he felt so damned good taking those pills that he doubled up on them, and then he said the overdose made him weak for the fight. Later on, he said he took the thyroid pills before the fight and also took some three hours after the fight. He don’t know when he took the fuckin’ thyroid pills. But I don’t think they had anything to do with what happened in the ring. It’s just that Larry Holmes is so damned good, and I know I’m good. Nobody can tell me I ain’t. Only way they can prove it is by knocking my ass out, and nobody can do that.

Ali didn’t win a single round during your bout last October. Were you surprised how easily you were able to beat him?

Holmes: No, and to tell you the truth, I knew I had the fight won after the first round. Ali was really finished after the sixth; only his willpower and determination kept him going. It was an easy fight, but all my fights have been easy except for Ken Norton and my second bout with Earnie Shavers. Besides those two I haven’t had any hard fights, because I just have too much ability for other boxers. Most fighters lose rounds; I don’t.

What made Norton and Shavers so difficult for you?

Holmes: They’re both very tough fighters. Norton has always been underrated, because after his first bout with Ali — he broke Muhammad’s jaw and won a decision-he never won a big fight. He lost twice to Ali, and also George Foreman knocked him out, and so did Shavers, but a few years ago everybody else Kenny Norton fought Kenny Norton beat. He was a harder hitter than most people give him credit for, and he was also a good all-around athlete. When Norton got knocked out by Cooney in May, he shouldn’t have been fighting in the first place. Earnie Shavers is a lot easier to hit than Norton, but if Shavers hits you clean on the jaw, he can knock you out with one punch. He is the hardest puncher I ever met up with.

Shavers proved it by flooring you with a right hand to the jaw. What did that feel like?

Holmes: There was no real feeling. All I felt was wham! — and I was down and trying to make sure I knew what I was doing. But there was no pain or anything like that. It was just wham! I got up and told myself I couldn’t make the same mistake twice, and I ended up knocking him out in the eleventh round. You know, Shavers was so sure he’d beat me that before the fight he went out and bought a $700,000 house. He’s still got it, but I don’t know for how long.

A number of sportswriters believe that up until you knocked him out, in the twelfth round, current WBA heavy-weight champion Mike Weaver gave you the toughest fight of your career. Do you disagree?

Holmes: Damn right I do. The only reason that fight looked hard was because I was sick. A few days before the fight I came down with a virus, and I was taking shots-antibiotics-an hour before I got into the ring with Weaver. I don’t want to make any excuses, but that’s really what happened. I probably shouldn’t have gone through with that fight.

Then why did you?

Holmes: Well, when it comes down to a matter of minutes and you’ve committed yourself to doing something in which people you like have hundreds of thousands of dollars on the line, you just don’t want them to lose the money-at least, I didn’t. But that’s nothing new, because I can’t even remember the last time I was 100 percent for a fight. For instance, I fought Ken Norton with one hand. Six days before we fought for the championship, I pulled a ligament in my left arm. I fought toe-to-toe with Norton for 15 rounds with my left arm shot, and I still found a way to make it work and beat him for the title. Against Ali, I had problems with my right hand; I broke it in a fight in 1976, and during training for Ali I thought I broke it again. It turned out to be a bad bone bruise, and during my sparring sessions I wore a foam cast under my gloves, and I had the hand treated two or three times a day by my doctor.

Gettin’ back to Weaver, I don’t think he would’ve lasted near as long if I’d been healthy. And if Weaver was supposed to give me such a hard fight, how come he only won 3 out of 12 rounds?

Weaver has since become the World Boxing Association heavy-weight champion. Do you have any plans to unity’ the title by meeting him in a rematch?

Holmes: Listen, there’s only one heavy-weight champion of the world, and that’s Larry Holmes. I hold the World Boxing Council title, and to me Weaver’s World Boxing Association title doesn’t exist. The WBA is an organization that goes along with apartheid in South Africa, which is the policy that allowed whites to kill blacks down there. This is why I don’t recognize Mike Weaver as a champion: because he went down to South Africa and fought there. And it’s also why he’s not listed in the WBC ratings. The WBC is recognized by more than 100 countries; the WBA is lucky if 35 countries recognize its titles. Anyway, Weaver ain’t gonna fight me.

Why? Is he afraid of you?

Holmes: Oh no, he’d like to fight me. He told me, “Larry Holmes, you got money. Give me a chance to make money.” I think he should make some money here in America, where I made mine. I didn’t sell anybody out by going against the government and fighting in South Africa, where whites are supreme and blacks are niggers.

But the real reason Weaver ain’t gonna fight me is because Bob Arum, his promoter, won’t let him. Bob Arum is not a fool, even though he acts like one. Arum has one fighter, one champion, to exploit, and that’s Mike Weaver, who’s as dumb as they come and who’s got ignorant people around him. Arum knows that Mike Weaver does not have the ability to obtain the heavyweight championship so long as he has to beat me for it. To build up his own name, Weaver told writers that the guy he KO’d in South Africa, Gerrie Coetzee, would have knocked me out because Coetzee hits harder than me. If that’s true, I wonder why I knocked Weaver out with an uppercut-and nobody gets KO’d by an uppercut, which is a setup punch for a left hook or a right cross.

Do you think of yourself as a heavy-hitter?

Holmes: I’ve knocked out eight of the last nine guys I’ve fought-ask them. I rate my left hand a ten, and it’s become my dominant weapon. After I broke my right against Roy Williams in ’76, I didn’t stay out of the gym. I kept working, even though I only had one hand to work with, and I developed a great deal of power in my left. If you saw my fight against Ossie Ocasio, you probably remember that I put him down with a left jab. I think I have the best left hand in boxing, and my right does the job, too. I rate my right hand an eight, but that’s compared to Earnie Shavers’ right, which is a ten. This kid Gerry Cooney, who’s being built up as a Great White Hope, has been saying he doesn’t think I hit very hard, but I don’t see how he can say that, since he never got hit by me.

Are you planning to give him the pleasure?

Holmes: Oh, I will give him the opportunity, but right now Gerry Cooney don’t know too much, because he hasn’t fought anybody good. His ability to take a punch hasn’t even been tested yet. Cooney knocked out Ken Norton, Ron Lyle, and Jimmy Young, but all those guys were washed up and no good when he fought them. Somebody representing Cooney made me an offer of $8 million to fight him, but I think the guy was probably jiving. If he isn’t, I’ll be happy to fight Cooney right away, but it looks like he’s going to fight

Mike Weaver this fall.

Who else?

Holmes: Well, right now I’m getting ready for Leon Spinks, and he’s an all out fighter. Spinks goes until he gets knocked out or until he knocks you out. After those two, maybe Weaver-if he gets by Cooney, and if Arum lets him do it. I don’t think they’re ready for me yet, but two young heavyweights I’ll have to start watching out for soon are Mike Dokes and Greg Page.

For several years, many people in the sports press have depicted you as boxing’s Rodney Dangerfield-a man who thinks he gets no respect. Do you feel that way?

Holmes: Well, I think people in the boxing world know there’s only one heavyweight champion and that nobody out there right now can whip me. People who think different than that amount to zero, nothing. I think they’re small-minded and just don’t want to give me the credit I deserve. I do feel I haven’t gotten the recognition I’ve earned, but it don’t really bother me. The only thing that would bother me would be if I didn’t get paid. No sense in my lying to you: I got in the game for one reason, to make money. And I’ve certainly made it. In the last two years, I’ve earned $15 million.

Did you ever think you’d make that much as a boxer?

Holmes: No, I never expected it. My goal was to get in and make enough to. own some kind of business and not have to work too hard the rest of my life. I thought that if everything worked out, maybe I could make a couple of hundred thousand dollars in boxing, but nothing like what I’ve made. I really didn’t know what millions of dollars was all about.

Have you since found out the answer?

Holmes: Yeah, and what I’ve learned is that it’s hard holding on to what you got. I get so many offers, and most of ’em are worth shit. You know how many people call me wanting to invest my money? You know how many diamond mines I could’ve bought? Or how many radio stations and hotels I’ve been offered? I can’t even count ’em. And I think I’ve probably been asked to buy_ a piece of every gas and oil well in the world.

Does that make you leery of talking to people?

Holmes: It’s no problem for me. I tell guys that if their deal ain’t guaranteed by the government, or if their company isn’t one I can get reports on, then forget it. I double — and triple-check everything before I let my money go. If you start looking to make millions and millions of dollars on investments, then greed can bring you down. But I’m just not greedy. I have a real simple plan about what to do with my money. It seems to me that you can live off the interest on a million dollars for a lifetime, so what would the interest on two or three million dollars do for you?

At a conservative estimate, it would probably bring you about $200,000 a year.

Holmes: Yeah, but would you need that much?

That’s something for you to answer, not us. Right now you’re earning $7 or $8 million dollars a year. Don’t you think it might be a little tough to scale down your standard of living?

Holmes: I don’t have to worry about that. Until a few years ago I lived on $8,000 a year, and my living expenses last year were only $20,000. I watch my dough carefully, and when I leave boxing, I’m sure people are gonna say, “There goes one fighter who wasn’t a fool.” I’ve only got a seventh-grade education, but I’ve got a Ph.D. in life.

How much of the money that you earn in the ring actually goes into your pocket?

Holmes: Almost all of it by now. When you first turn pro, your manager usually gets one-third of your money and ten percent goes to your trainer, so most young fighters get about 50 percent of what they make. That’s okay when you start out and you’re fighting for $1,000 or $1,500 a bout, but later on you become the power, and you can give them what you want.

Still, you’re in a sport that’s infamous for the way its champions earn small fortunes and then somehow end up penniless. Why do you think that happens to boxers?

Holmes: Boxers can be taken advantage of, because they don’t like to listen and they really don’t know who to listen to. They’ll get somebody who wants to help them, and they won’t listen, and then someone will show up who wants to rip them off, and they will listen. But like any goddamn thing, all you need is some common sense. I mean, when people come up to me and start talking about how I should have some tax write-offs and how I can make tax-exempt money by investing with them, I say, “Hey, if it’s so good, you invest in it.” The only thing I put my dough into is a bank.

If you earned $15 million in the last two years, what do you expect to make in the next two?

Holmes: I don’t know, because I don’t want to stay in boxing that long. I’ll take some more fights, but I’m not gonna be in the ring too much longer. I’m happily married, I’ve got a baby daughter, and I just want to be able to spend time with my family.

Have you already decided on a retirement date?

Holmes: No, I haven’t made any real decision on it yet. One day I feel like quitting right then and there; the next day I feel like going on for two more years. I play it by ear, but I know this much: I’m not gonna keep fighting for as long as a lot of people expect me to. I’m not gonna wait around to get old before I fight a kid like Gerry Cooney.

When Ali fought Floyd Patterson, he was 30 and Patterson was 38; when I fought Ali, I was 30 and he was 38. That’s not how I’m gonna go out. When I retire, I want to go out on top.

Ali also used to say he wanted to go out on top; yet obviously he wasn’t able to do that. Couldn’t the same thing happen to you?

Holmes: I don’t think so. You gotta remember that Ali and I are two different people in a lot of ways. Ali likes the lime-light, the glamour, being on television and having people recognize him. Larry Holmes don’t care too much about doing talk shows and such. Ali still supports a big entourage of people; Larry Holmes has only four people working for him fulltime. Ali likes the big cities; I don’t. I love living in Easton, Pennsylvania, because it’s quiet, it’s in the middle of everything, it’s a nice place for my kids to grow up, and nobody hassles me here. I can own a comfortable house anywhere in the world, and I’ve traveled around to the big cities, and I’ve seem ’em all. But I always come back to Easton.

I guess the big thing is that I just don’t need more money, which would be the only reason to keep fighting. Let’s say I could make as much money as Elvis Presley, John Wayne, or the Rockefellers. What would I do with it? The only businesses I want to own are a few little ones in the Lehigh Valley. I don’t want to own a newspaper or an airline or Rockefeller Center. I don’t care about all that, because my theory is that it was here when I had nothing and it’ll be here long after I’m gone. I don’t want to be Howard Hughes. I want to be a human being, and I want to live like a human being.

Then you have no more goals left as a boxer?

Holmes: Except for making $100 million in the ring and making every member of my family a millionaire, no, none that I can think of. But I have a lot of goals outside the ring.

What are they?

Holmes: I want to help kids and give them opportunities that I didn’t have when I was growing up. I like being chairman of the local Boys’ Club and working with retarded kids and being very active in the NAACP. Winning the title somehow gave me the desire to do these things, although I’ve been active in the NAACP for a long time. I’m involved now in trying to get more people to join the NAACP. A whole lot of black people have the wrong impression about that organization. A lot of them say that the NAACP is an Uncle Tom group because white people are involved in it. Well, the NAACP is an organization for all people, and it tries to help people who face racial or sexual discrimination, which is why a lot of women are joining up now. Everyone under the sun is God’s child. People are created equal and should be free to become what they can make of themselves.

We don’t doubt your sincerity, but if you feel that way, don’t you think it’s a little odd that you make your living beating people up?

Holmes: I don’t think it’s odd. You want to know something? I like to fight. It relieves tension for me. It puts me in a good frame of mind, and it just makes me feel good all over. The only time fighting’s hard is when I have to sacrifice and spend months and months in training. Boxing is what you make it; it can be good for you or bad for you. A lot of guys take out their feelings on their wife, but if I get upset, I can take it out on the heavy bag. I like that.

Prize fighting is terribly dangerous. In 1980 alone five professional boxers were killed in the ring. Do you ever worry that it could happen to you?

Holmes: No, never. If it’s my time to die, then I’ll die, but not before. You can jump off the damned Empire State Building, and if it ain’t your time to go, you won’t.

We’re a lot more skeptical than that. In June, 1980, in a preliminary bout before the Sugar Ray Leonard — Roberto Duran fight in Montreal, lightweight boxer Cleveland Denny died after being knocked out by Gaeton Hart — and many ringside observers believe that if the referee hadn’t been 71 years old and unable to stop the fight when he first attempted to, Denny would still be alive.

Holmes: That don’t change nothing. It still was Denny’s time. I don’t give a damn if the referee couldn’t see. It was that man’s time to go, and that’s the way I look at it. I don’t think boxing is as dangerous as ice hockey or football, in which 11 guys jump on your ass. How many football players have you seen in wheelchairs, and how many serious injuries are there every year to hockey players? A lot, but you never hear about them. But every time something happens to a boxer, there’s all this talk about it being such a dangerous sport. I don’t feel that way.

Champions rarely do, Larry. In any event, you’ll be 32 in November, and judging by what you’ve told us about the sport, your own boxing skills will shortly begin to erode. When that happens, do you think you’ll immediately recognize it?

Holmes: I hope so, but I don’t think so. There’s always something you do that wasn’t there before, and I guess you think that the stuff you had before is always there. You know, Ali finally recognizes that he isn’t what he once was, but he can’t really believe it. But there comes a time when you’ve got to believe what’s real and what isn’t. Ali just can’t do the things he did when he was 30 or 20. They say you get better with age, but that’s not always true. You get worse in certain things, especially boxing. That’s the way it is, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

Ali came out of retirement, for your fight, and recently so did Ken Norton for the Cooney fight, and both were embarrassed in the ring. If you retire can you conceive of ever allowing yourself to be lured back into boxing?

Holmes: Only time will tell. Look, I think a guy can make a comeback if he has the determination and will to do so, but that’s not for everybody. If I was Kenny Norton, I wouldn’t have done it, but I’m saying that because that’s the way I feel now. If I’d been in Norton’s position and had his needs and desires, I might have done the same thing he did. All I can really know about is myself, and every day I just hope and pray I’ll always feel the same way about retiring that I do today. I just hope I’ll know when I should retire for good. In the meantime, I’m the heavyweight champion, and right now nobody in the world can beat me except myself. If I sit back and think things are gonna go real easy, then I’m in trouble. As long as I train and I’ve got fighting on my mind, nobody can whip me.

You’re one of the most confident athletes around. Was there ever a time when you doubted your ability?

Holmes: No, but there was a time when some so-called experts doubted me, and I still remember one of them in particular. It’s hard to forget these people. Gil Clancy, who managed Emile Griffith, once had a chance to sign me, and he blew it. I’d had about 22 amateur fights, and a man who was gonna help me turn pro wanted an expert opinion on my progress, so he brought me to see Gil Clancy.

Well, I got into a ring with one of Clancy’s top-notch professionals, and I did very well against him. But Clancy told the guy that I could never become a champion or even a contender and that I’d never amount to anything. Clancy said that I didn’t have the punching power of George Foreman or the boxing ability of Muhammad Ali, and that between other fighters like Frazier, Norton, Ron Lyle, Jimmy Young, and Jerry Quarry, there really was no room for Larry Holmes. For some reason, he didn’t realize that all the fighters he’d mentioned were getting old and that a new wave of heavyweights was coming up. He also should have seen that here was a black man who had the desire and determination to fight, and who’d proved it against one of Clancy’s own pros. But he didn’t see that, because his vision is worse than Ray Charles’s. He told the man to give me a job driving a truck, and I never forgot that. In plain English, fuck Gil Clancy. Anyway, that should give you an idea how much so-called experts know about boxing.

Is being the world heavy-weight boxing champion all you thought it would be?

Holmes: That’s hard for me to answer. I expected to be in the limelight and for people to be saying hello to me, and I suppose I have that, but I don’t feel particularly like a champion. I mean, I wish somebody would tell me how you’re supposed to feel when you’re a champ, because I don’t know yet. I’m still waiting for that great feeling you’re supposed to get.

How do you feel?

Holmes: Like I did when I didn’t have no money, like I did when I didn’t have no car or no shoes. When I thought about winning the heavyweight title, I used to think about sitting back and smoking cigars and having people buff my nails and wait on me. But I think there’s more to being a champ than that. I hope there is, you know?

Larry actually maintains a website currently. Sure they’re trying to sell athletic gear (y’know, because George already claimed the kitchen grill market), but boxing fans will enjoy the site for the history presented. … Hey, we just posted a story that ran in Penthouse Magazine 40 years ago. We appreciate history around here. … As a final note, you also might find an interesting comparison between Larry and Connor McGregor. We did.

Go Larry!