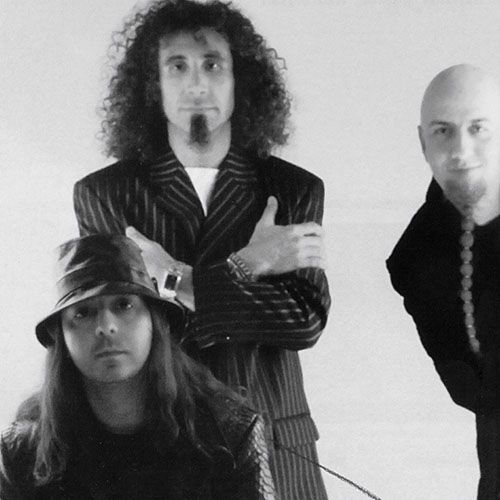

Four years ago, Linkin Park’s Chester Bennington “never would have imagined” the band’s mega-success today. As they prepare their new CD, he explains how these virtual unknowns became multiplatinum stars.

One Step Closer to the Top

It’s a crisp blue-sky day in Los Angeles, and Linkin Park’s rapper, Mike Shinoda, is standing outside The Lounge, a hipster club a blink outside ritzy Beverly Hills, surrounded by a handful of the deejays and emcees that appeared on the band’s remix project, Reanimation.

Laughing and goofing with the crowd, Shinoda is oblivious to the fact that Evidence, emcee and producer of the hip-hop outfit Dilated Peoples, has stopped a fiftyish female jogger. “Do you know who Linkin Park are?” Evidence asks the confused woman. She shakes her head. He asks if she has kids , and she nods. “Shake this man’s hand,” he says, leading her to Shinoda. ’Tell your kids you met Mike Shinoda from Linkin Park.” She smiles kindly, looks around, and goes back on her way, clearly not sure what just happened.

This scene could have been played out hundreds of times over the past three years as the Linkin Park sextet went from virtual unknowns to multiplatinum stars with a combination of hard work, incendiary live shows, and an infectious-as-hell collection of songs. Hybrid Theory, the Los Angeles-based band’s 2000 debut, has spawned the radio hits “Crawling,” “One Step Closer,” and “In the End,” while selling somewhere in the neighborhood of 12 million copies around the world.

An hour or so after Shinoda’s impromptu introduction to the unassuming jogger, his vocal sparring partner, singer Chester Bennington, is tucked away in a corner booth at The Lounge. He looks slightly bemused when asked if he ever pictured Linkin Park’s wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am success when the band gelled four years ago. “No way,” he says. “I never would have imagined this would be happening. My goal was to be in a band that I enjoyed again. … Getting to this point was nothing we ever planned on.”

Indeed, the fate of the band then known as Xero looked dim five years ago. Shinoda, guitarist Brad Delson, deejay Joseph Hahn, drummer Rob Bourdon, and bassist Dave Ferrel (aka Phoenix) had been busy writing and playing at L.A. clubs, but nary a record label was paying attention. Meanwhile, in Phoenix, Bennington was unhappily playing with a band called Grey Daze, and the singer was about to give up. “I had lost my love for playing with other people because I didn’t like anybody I was playing with,” Bennington recalls. “And the people I did like when I was playing, the final outcome put a bad taste in my mouth.” It seemed to him that the only way to discover something new was to leave. “I had basically exhausted the local scene there.”

Then he received an out-of-the-blue, sounds-too-good-to-be-true call at work from one of his old music-business friends, Scott Harrington. “I don’t even know how he got the number,” Bennington recalls. “I think he probably called my wife and got the number. He said to me, ’There’s this band; they’re looking for a singer. They’ve got a lot of potential and they’re good. They’ve got some interesting people looking at them.’ “ Harrington stressed that this would be an extremely good opportunity, so when Bennington got a Xero tape from Jeff Blue, vice president of A&R at Zomba Music, where the band had a publishing deal, he scooted into a studio to record some vocal parts. “I called [Blue] on Sunday and said, ’I can either mail it out to you or I can be in L.A.,’ “ Bennington says. “I just felt that it was going to be something that I would have a lot of fun doing and I could contribute to. I felt the music was extremely powerful, and something inside told me that this was worth taking the risk.”

So is this basically one of those “quit your job, move to L.A., join a band, and sell millions of CDs” stories? Bennington laughs at the question: “For me, starting something new with new people in a fresh place was worth the chance, it was worth the risk. If it worked out, awesome, and if it didn’t, then make it work out.”

The band, which was by then known as Hybrid Theory (they changed the name to Linkin Park after a potential legal conflict surfaced) spent a year putting songs together and playing showcase performances for record labels. As it turns out, Bennington’s sacrifice and push was the final piece to completing the band’s puzzle. “I hope I’m not overstepping my bounds,” he says. “I put a lot of my personal stuff on the line to join the band and brought a lot of focus to the band. Hopefully it acted as an inspiration to say, ’Hey, this is worth taking the risk. Let’s do this.’ I think that helped the songwriting on everybody’s points, because we had a lot more time to spend on the songs and the music. It really helped [us] push ourselves to write better songs and be more dedicated to the band.”

Other than for the album’s musical blend, Hybrid Theory stuck out almost immediately upon its release for its lack of profanity. “I’m probably one of the most vulgar people if you meet me in a casual setting,” the singer admits with a laugh, “and it’s not like we’re a bunch of goody-two-shoe guys. Trust me, we’re still a rock-’n’-roll band. But the thing is, we never even consciously did that. When it came time to write the songs, Mike and I sat down and wrote the lyrics, and we wanted them to be honest and we wanted them to have a lot of power and depth. We never sat down and thought of ourselves as a band that should say ’fuck’ every two minutes. We don’t think of music that way.

“To me, we come to songwriting music first, and the lyrics have to have a meaning, they have to have a story, and they have to make sense to us,” Bennington says. “So, luckily, [not swearing] saved us ten cents on every copy for a parental-advisory sticker. Really, that’s the only benefit we got out of it. Nobody seems to really focus on that. Our fans, anyway, focus on how they can relate to everything. It’s cool because their parents aren’t bitching at them for it, and I guess that’s another plus. We never sat down and said, ’We can’t cuss on this record.’ “

Of the songs on their debut, Bennington feels close to “Papercut,” “Points of Authority,” and “Crawling.” Fans, he says, relate to the lyrics because of the honesty of the words. “It’s kind of general, and that’s what we wanted to hit, something that everyone in every spectrum of life can relate to,” he says. “I think that also the way that we mix the music together is not the conventional way of doing it. A lot of kids say they admire the way we melt the parts together. So I think between those two things, it’s something new and the kids can relate to what we are talking about, and I think that is what’s connecting to them.”

Impacting the lives of their fans is one of the most rewarding aspects for Bennington. “We’re just kids, we’re young,” he admits. “We’re not claiming to be professors on life or know anything that nobody else knows. We were young people and we expressed in one way or another how we were feeling at the time. That’s how we write. When we do that, we find that people can relate. Lyrically, people can relate to that, and it changes their lives.’’ The band has handfuls of letters from kids who tell them the group’s lyrics have helped them communicate with their parents or get over broken hearts. “The fact that our music helped that person through that situation or a situation like that is rewarding,” Bennington says. “It’s like our accidental good deed that we stumbled upon.”

While many of Linkin Park’s fans were catching the themes of disenfranchisement and recovery, others used the band’s lyrics to explain feelings they couldn’t put into their own words. One of those fans, 15-year-old Charles Andrew Williams, wrote out lyrics to the band’s song “In the End” – ”I tried so hard and got so far/ but in the end, it doesn’t even matter” – stuck the page to the speakers in his bedroom, and went to his Santee, California, high school and shot 15 students, killing two. Williams, who has since pleaded guilty to murder charges, has not commented on the band, but many politicians and members of the mainstream media have used the connection to make headlines. Linkin Park’s Mike Shinoda, speaking to Time magazine in one of the only statements on Williams that anyone in the band has issued, said, “Yes, that kid connected with the lyrics, but so did a million other people, totally different kinds of people.”

Even as Bennington was singing those lyrics, he was battling a relapse into the drug addiction he had been treated for as a teenager. He started drinking heavily while the band was on tour in fall 2001, and has said, “I found myself not saying no to other things, things that would have made me another rock-’n’-roll cliche.” Since January 2002, Bennington has been clean and sober. “The thing about it is, that kind of stuff made me a little reclusive,” he says at The Lounge. “It tapped into the darker side of my personality, which I guess enabled me to do the stuff that I do now. But I don’t give the situation like that credit for what is happening. I think that’s glorifying a horrible thing. I don’t give sexual abuse or drug abuse or personal problems to that effect fake glorification. I think you’re dealt the hand that you’re dealt, and you play it, and you play it to the best of your ability.”

The best of Bennington’s ability enabled him to turn some of his darker days, including the battle with drugs and a five-year period in his childhood during which he was molested, into emotional lyrics that garner a response in listeners. “Misery likes company,” he says, “and I think the best company for misery is music, because it turns it into something positive, and that’s a good thing. For me, it’s really hard to make a very credible happy song. It’s hard to be creative if you’re not fucked up in some way, even the most sane, together people. Like Moby is a really positive energy, and he still has to have some kind of issues; there’s got to be something pushing him to be creative besides his positive energy.”

Through all the band’s – and Bennington’s – challenges, the members have grown closer. “We probably get along better now than ever,” says Bennington. “We always got along, but at the same time you’re on the road for two years, and you like spending time together, but we also like to have our own lives, our own space, and do our own thing separate from each other. That’s something that’s inevitable. We aren’t the type of band [in which] somebody is getting more attention than somebody else. Nobody is jealous. And if anybody does something that’s a little out of hand, you’ve got five other guys in the band that are grounded enough to tell you. We have each other’s backs.”

Along with that camaraderie, Linkin Park’s fans continue to demonstrate their appreciation. From Bennington’s perspective, it’s a two-way street. “The key to what we’re doing is maintaining the relationship that we started with our fans,” he states. “That’s been extremely critical in how the record did and is still doing. It’s definitely the most important aspect of what we’re doing.” So that’s the key to longevity? “It certainly doesn’t hurt,” he says. “There are a lot of bands that I guess don’t pay that much attention to their fans that still have longevity, but I think in our case that we’re already going down as the band that cares about their fans. I think that’s going to be part of our legacy.”

Part of the way Linkin Park paid back its fans after the success of Hybrid Theory was to spend a whopping 325 days on tour in 2001. Not only did the guys headline their own run of club shows, they played on the Ozzfest and Family Values tours and organized the Projekt: Revolution tour with Cypress Hill, Adema, and DJ Z-Trip. Bennington is still amazed that Linkin Park headlines over certain bands. “I have a hard time headlining over [the band] (hed) p.e. ,” he admits. “It’s like the pecking order isn’t right. At the same time, you have to be realistic. They are a great band and I admire them, but position on a bill doesn’t mean anything. It’s about the package. The headliner doesn’t sell the show, the package of the show sells the show.” It’s obvious, he allows, that more people will come to see a band the more records they sell. “At the same time, if you’re an artist like Basquiat and your idol is Andy Warhol, and you aspire to be at that level and then you go beyond it, it’s hard to find yourself beyond the level of greatness that you looked up to,” Bennington says. “It gets interesting sometimes.”

The key to the successful melding of genres, he adds, is the new attitude in today’s music world. “The scene now is unlike the scene in the eighties, where there was a lot of friction between genres. Now people are just happy to be playing with each other. I wish every band sold as many records as we did. I want them all to be successful. That’s what’s really cool about this scene. We all help each other; we all support each other. You’re not going to see a Vince Neil and Axl Rose get in a fistfight onstage nowadays. It just won’t happen. There’s much respect now for music. Music is better now than it was in the eighties. I think fans don’t have a hard time bringing genres together, [and] I think bands are easier about it.”

Linkin Park’s collaboration with the genius turntable collective the X-ecutioners is one outstanding example of just that. The song “It’s Goin’ Down,” which was on the X-ecutioners’ 2002 Built From Scratch, was a blend of Linkin Park’s metal and the X-ecutioners’ scratch talents. The X-ecutioners’ Rob Swift echoes Bennington’s ideas about genre crossing. “I hate people that listen to just one form of music. You’ve got to be able to expand your horizons and really experiment,” Swift says. “In doing so, you’re able to reach some people that don’t know about you and your music. I think doing the Linkin Park song is going to help us, because we’re going to reach Linkin Park fans that don’t know about the turntable. In turn, for Linkin Park, doing a song with us helps them because our fans will learn about them and learn about their music and want to support them as well. Overall, it’s about experimenting and trying to grow musically.”

Linkin Park expanded on the genreblending theme on Reanimation. The release, which was Shinoda and deejay Hahn’s baby, featured interpretations of the band’s debut album by such hiphop legends as Alchemist, Kutmasta Kurt, and Evidence. A handful of Linkin Park’s harder brethren, like Jay Gordon of Orgy, Aaron Lewis of Staind, Jonathan Davis of Korn, and Stephen Carpenter of the Deftones, also contributed to the collection. “[This] is like a pipe dream of a project,” Bennington says. “This is a dream come true for us because we get to work with a lot of people, everybody that we respect, no matter what kind of stuff that they do.”

And that brings the band to its proper sophomore release, due from Warner Bros. Records early this year. Any outfit that has sold close to 12 million copies of its debut might feel some pressure, but Bennington says he and his colleagues haven’t yet. “The only pressure is the pressure we put on ourselves sometimes,” he says. “It’s like Hybrid Theory is a phenomenon. We never expected to do that; we don’t expect to do that again. All we expect of ourselves is to write another good record. It’s up to the people who listen to it whether they like it or not. You can’t predict that.”

To be sure, Linkin Park fans are hot and heavy to hear what the guys have up their sleeves. Bennington points to Reanimation as a good jumping-off place. “I think the remix album is a good example of some of the direction that we’re going to go into,” he says. “It’s a good example of our diversity. As far as the hip-hop vibe, the beats are going to be harder and they’re going to be better. I think primarily the beats and the electronica aspect of our music is going to be explored a little more.”

Where the Linkin Park contingency was hitting wall after wall five years ago, Bennington reports the band is now driven like it’s 1997. “We’re like a freight train, and it’s going to take a lot of energy to stop this train,” he says with a laugh. “I think as long as we’re making the fans happy, then they’ll continue to want us to make records. As long as they want us to make records, we’ll do it. When people want us to stop making records, we’ll probably go figure something else out. [We] probably won’t even stop then. We’ll probably try to regroup, lock ourselves back in our rehearsal space, and go to it, figure out where we went wrong and fix it.”