When “The Pill” came out, Southern preachers gave sermons about how I was preaching having sex in a different way. Half the congregation would then go out and buy the record to see how bad it was.

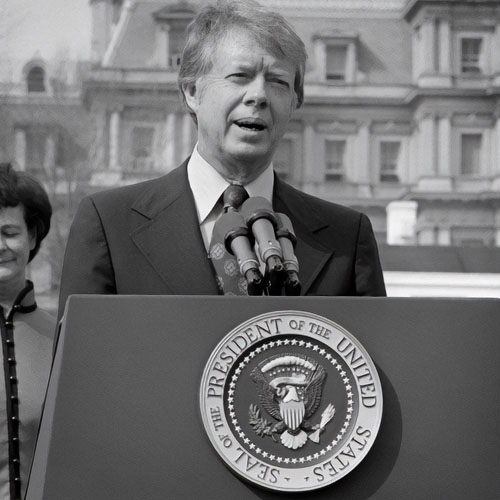

The Penthouse Interview with The Coal Miner’s Daughter

It’s been 20 years since Loretta Lynn first surfaced as a singer, and in the course of becoming the queen of country music she’s recorded more than 50 albums, was the first woman ever named Entertainer of the Year by the Country Music Association, and is also the first country musician whose autobiography (Coal Miner’s Daughter) became a best-seller. As we went to press, the movie version of her book-starring Cissy Spacek-was set to open in theaters across the nation.

The object of all this attention is a five-foot two-inch, blue-eyed brunette whose voice is as clear as polished crystal and as pure as a country stream. An accomplished songwriter, Loretta Lynn has never lost a sense of her rural roots, and her songs invariably focus on the problems backwoods women have with their hardworking, hard drinking men. Unlike most of her colleagues, however, Lynn doesn’t much care for walking the floor and crying her eyes out over a two-timing mate. She’d rather fight fire with fire, which explains why many of her past hits have borne such titles as “The Squaw’s on the Warpath,” “Fist City,” and ” I’m Gonna Make like a Snake.” Right: Loretta is country.

The second of eight children born to Clara and Melvin Webb, Lynn was born and raised in Butcher Hollow, Ky., a poverty-stricken coal mining hamlet in the eastern part of the state. She once told writer George Vecsey, “Im always making Butcher Hollow sound like the most backward part of the United States — and maybe it is. Lynn grew up without the niceties of indoor plumbing and electricity, and as a child her wardrobe included dresses made of flour sacks. She learned to read in a one-room schoolhouse that was a two-mile walk down the mountain from her home, and if it all sounds a little like Abe Lincoln in Illinois, well, that’s the way it was.

Loretta’s education ended abruptly when she was 13 and met a recently discharged 22-year-old army vet named Oliver Lynn at a pie supper sponsored by her school. Lynn’s family had called him Doolittle since his infancy; his friends called him Mooney because he’d once had a job delivering moonshine whiskey. Doo courted Loretta for a month, after which they were married. On her wedding night, Loretta got to wear her first nightgown which she put on over her clothes. As she notes in her autobiography, sex “was all a mystery for a long time.”

Soon after their marriage, the Lynns moved to the state of Washington, where Doo worked as a logger and ranch hand. By the time she was 18, Loretta had given birth to four of her six children, and for several years thereafter she was content to look after her family. She’d probably still be a housewife today if Doo hadn’t bought her a $17 guitar and urged her to try singing in a few local clubs. When Loretta won first prize of $25 in an amateur-night competition sponsored by a Blaine, Wash., bar, the couple took off for Tacoma to see if they could wangle an appearance for her on a regional television show hosted by singer Buck Owens. Owens put her on, and the show attracted a sponsor, who came up with enough cash for the Lynns to travel to Los Angeles and cut a record for their own newly formed Zero label. The result was “Honky Tonk Girl, which climbed to fourteenth place in Billboard’s country music chart. Loretta Lynn’s career had been launched.

To interview the singer, Penthouse sent free-lancer Lawrence Linderman to meet with Loretta Lynn in Nashville. Linderman reports:

“Over the years I’ve found that country music singers are the nation’s least pretentious show business performers, and Loretta Lynn is no exception to that rule. When I met her recently at her offices in Nashville’s Music Circle, she greeted me warmly, giggled a bit about doing a Penthouse interview, introduced me to her friend (and office manager) Lorene Allen, and then made sure there was plenty of coffee and soft drinks and candy and cookies around in case the big boy from Penthouse needed anything in the way of refreshment. Lynn is refreshing enough by herself. A pint-sized bundle of energy and easy humor, she’s a fine-looking woman in a weathered, classic, country way. In fact, if Grant Wood had painted American Gothic with a younger couple, Lynn would have been a perfect model for the wife.

“Loretta seems almost incapable of artifice. Actresses appear for interviews expensively dressed, exquisitely powdered, and beautifully coiffed; Loretta showed up in a knockabout dress, without makeup, and her hair surely hadn’t been styled that day by Mr. Joe Bob or whoever Nashville’s hot hairdresser may be these days.

“In any event, after some brief conversation we got down to business. In the last few years Loretta has become increasingly identified as an advocate of women’s rights, and with that in mind, I began our interview.”

More and more of your recent songs have been about women standing up to their men, not by them. For instance, in “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby,” you state, “There ain’t no man alive who can match a woman trick for trick.” Lyrics like that sound as if you have a sexual score to settle. Do you?

No, but that line sure got the men’s attention. But I didn’t put it in there because I think a woman can outdo a man.

I just think there’s things men can do that women can’t, and that there’s things women can do that men can’t.

Were those card tricks you had in mind?

Not hardly. That song also has a line that goes, “Up to now I’ve been an object made for pleasing you, but times have changed and I’m demanding satisfaction, too.” Times have changed, and when it comes to satisfaction-about sex or anything else-I don’t think men should be the only ones who get to be happy. I think women have the right to be happy and satisfied, too.

Isn’t that quite a departure from the usual sentiments voiced by female country singers?

I’m not sure that’s so. I doubt if country people want to hear this, but I came to Nashville in 1961, and since then country music has changed a whole lot. The thing is, it’s been progressing in such a gradual way that up until recently we haven’t realized it. Today you can just be a lot straighter about things. For instance, when I first came to Nashville, I wrote two songs “Don’t Come Home ADrinkin’ with Lovin’ on Your Mind” and “You Ain’t Woman Enough to Take My Man.” I don’t think either of them would get anybody worried today, but back then the girls would be either too scared or too embarrassed to sing ’em. At the time, girl singers were doing 1-love-youtruly kinds of things, but I came in fightin’ over my man ’cause he was stepping out with somebody else and I was promisin’ to do the same thing, or I was doing the same thing. I was just a little bit braver, I guess, than most of the other singers, and I was also the first one to get my records banned. But every record of mine that was banned became number one.

By banned, do you mean radio stations wouldn’t play those records?

That’s right. A lot of radio stations banned “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’.” I remember that a big 50,000-watt station in Chicago-WJJD-wouldn’t play the song ’cause they thought it was dirty. As far as I was concerned, there was nothin’ dirty about it, but a lot of radio stations objected to the last chorus: “You never take me anywhere because you’re always gone, / Many a night I’ve laid awake and cried the whole night long/ Then you come in a-kissin’ on me, it happens every time/ So don’t come home adrinkin’ with lovin’ on your mind.” As I said, other girls weren’t singing that kind of stuff; so it always kept me one step ahead. After that I had a song called “Another Man Loved Me Last Night,” which was about a woman steppin’ out on a man who’d been steppin’ out of her. That song was Bible Belt banned, and after that came “The Pill,” and that was banned all over.

Did that come as a shock to you?

Sure it did. I couldn’t understand why anyone would even think about not playin’ a record called “The Pill” when women had been taking the pill for 20 years. What was the big deal? When “The Pill” came out, southern preachers gave Sunday sermons about the record and how I was preaching having sex in a different way. The next day, half the congregation would go out and buy the record to see how bad it was.

It wasn’t bad at all. A lot of doctors told me they’d been trying to get birth control information to country women who were back in the woods and that my song had done more for them than all the literature they’d put out. You know, I had four children by the time I was 18; and if they had had pills back when I had my first boy, why, I’d have eaten ’em like popcorn. Women really loved the song, and a lot of them got on the pill as a result of it. Now, maybe the pill wasn’t good for a lot of women-even an aspirin can affect you if something’s wrong with youbut havin’ babies wasn’t always good for them, either.

How did men react to “The Pill”?

It seemed to offend a lot of them, and I just couldn’t believe it. Our house was swamped with calls from men, and none of them was complimentary. Disc jockeys were a little bit hateful about playin’ the record, and I remember one of ’em calling me up and saying, “Good morning, Loretta. Have you taken your pill today?” And then I had all kinds of people asking me if I was a women’s libber.

Are you?

Well, I’m for the women, but I’m not the kind that marches in the streets and burns my bra and carries on. But I do think that if a woman does a man’s job, then pay her equal. And if you don’t want a woman to get a man’s pay, then don’t hire her and then raise the man’s pay so he has enough to take care of his family and his wife don’t have to work. But otherwise, if a woman works alongside a man and does the same job, why not give her the same pay? She’s earned it, and she deserves it.

Do you think you put men off by saying such things?

No, because both men and women come to my shows and buy my records. But I know that women like me, and it’s very hard for a girl to be liked by another girl, ’cause women are real catty people. I mean, when a woman walks by another woman, she’s gonna be looked at from the top of her head to the bottom of her feet, and you’ll hear things like, “That’s the ugliest dress I ever seen, 11 or “Look at them shoes,” or “Hey, that girl don’t have no bust.” I don’t believe I’ve ever heard men talk about other men that way.

Still, I always let the women know I’m on their side. That don’t mean I’m not for the men, but as far as havin’ me sing about sittin’ home nights and havin’ a hopeless love, well, I ain’t got time for that stuff. And I really do believe that when guys are out by themselves on a Friday or Saturday night, drinking their beer and having a good time, well, when they walk up to the jukebox and they hear “Another Man Loved Me Last Night,” they start to think about it. They’re going to say, “Hey, I’d better get home. I may be missing something if I don’t.” And they’d better get home, ’cause more and more women aren’t going to always be there, pining for ’em.

You really see that happening in rural areas of the country?

Sure I do. You know, the tradition handed down to us is that women stay home, take care of the family, and that it’s okay for a man to do whatever he wants and to go wherever he wants. But if his wife gets all dressed up and goes to town, well, that’s just awful. Very few women used to do that, and when they did, you know what they were called.

It’s different today, and I’m glad, because a woman can get all fixed up and go someplace and have a good time without doing something wrong. You know, if I ever was to go out and go to bed with a man other than my husband, Doo, it wouldn’t be just a one-time thing. The man would have to mean an awful lot to me, and I think the majority of women feel the same way.

Were you that unyielding when you were on the road by yourself for several years?

Yeah, and it was very tough, because I was scared to death to travel alone and I didn’t know that much about life. When I first started singing, I’d already had my four kids, and I was about 25 and making $50 a night. I remember going all the way from Nashville clear into Colorado by bus with only my guitar for company. My husband couldn’t come along because we didn’t have a car good enough to make the trip, and even though the bus fare wasn’t expensive, we needed that $50 real bad.

So I got to this club-I can’t remember the town right now-and I did four half hour shows. When I finished the last one, somebody came running over and told me I was wanted on the pay phone in the hallway. I picked up the phone, and this guy on the other end says, “Would you like to make some money tonight?” I said, “Oh, yes!” Well, the guy was having a party after my last show, and he wanted me to entertain the fellas. I asked how long he wanted me to sing, and he said, “Who said anything about singing?” I didn’t know what he meant, but a woman named Loudilla Johnson heard me talking and grabbed the phone and cussed the guy out and then hung up. Loudilla, who’s now president of my fan club, said, “Loretta, you’ll have to learn a lot better than this. That man doesn’t want you to sing.” She then explained just what it was he did want me to do, and I said, “No, you’re kidding!”

But she wasn’t kidding, and after that I got propositioned quite a bit, and I soon had my guard up to everyone. I mean, if a man just smiled at me, I’d think, “Uhoh, here it comes.” I was real backward and bashful, but I finally got to the point where if a man did proposition me I was able to say, “No, I’m married.” Penthouse: Aside from that, was being on the road fun?

No, it was kinda upsetting. I’d work these clubs night after night, and I’d see men come in with women who weren’t their wives, and the next night I’d see their wives come in with other men. I’d get to thinking, “Well, what’s my husband doing tonight?” Every time I came home, I’d ask Doo, “Where were you Saturday night?” He’d say something like, “Well, I went downtown to Tootsie’s,” which is a famous country music bar in Nashville. I’d ask him who he was there with, and then we’d get to quarreling, because after what I’d seen I was sure Doo was doin’ the same thing. But I had to get over that, because I was getting sick from it. I was either gonna get it out of my mind or quit singing. So I never again asked him where he’d been or how long he stayed. It was just a real hard time for me, and when I started getting more jobs, it got harder. My brother would drive me 400 miles a night between shows. I’d sleep in the car and take baths in the sinks of filling-station washrooms because we didn’t even have money to check into a motel.

How long did that kind of situation continue?

For about eight years. After that I started getting better bookings, and we started staying at nice little hotels. And when I was first able to order dinner up to my room, man, I really went at it.

I shouldn’t even tell you this, because it shows how dumb I am, but about four years ago Conway Twitty and a bunch of us went to the downstairs restaurant in the hotel we were all stayin’ in. I’d always had my food sent up to the room; so I kind of enjoyed the meal, and when we were through Conway just signed his name and room number to the check. And I remember asking him, “You mean you can come down here and eat and just sign for it?” I never knew you could do that! I guess that’s got to do with growing up way back in the mountains of Kentucky, where you didn’t have nothin’ and didn’t know nothing.

Does it ever occur to you that you might be part of a vanishing breedthat even in remote reaches of Appalachia, television has helped make the kind of upbringing you· had almost obsolete?

You might have something there, because I’ve noticed that a lot of the girl country singers coming up now are a lot less country than I was. I really saw that when Dolly Parton and I got to talking at a disc jockey convention not too long ago. Dolly was raised up like I was, meaning her people didn’t have a pot to do it in, or even a window to throw it out of.

When Dolly and I grew up, we both lived in houses without screen doors or screens on the windows. So we got to talkin’ about what would happen when mother would tell you company was coming and to shoo all the flies out. You had to grab a towel and run through the kitchen shooin’ flies out, and you’d have the door open-you’d get half of ’em out and then slam the door so they couldn’t get back in.

Well, Dolly and I were going on about this, and pretty soon we were on the floor laughin’ about it, and none of the other girl singers there could understand what we were talkin’ about. None of ’em had ever gone through anything like that.

Do you feel that the way you both were raised has a lot to do with the success you and Dolly Parton have had?

I think it’s got a lot more to do with it than people would ever suspect. When you come up hard, you know you don’t want to live that way all your life. If you get a chance to put your foot in the door, you known you’re gonna push it through; and when you do make it, you get to thinking, “Is this the best way I should go?” You plan your route pretty closely, and you also hold on to your money, because you know you might not be as successful tomorrow as you are today.

Do you ever worry that country music is changing in ways that you’re not?

Honest, I don’t. It’s true, the whole country music scene is changing. A lot of the different young stars aren’t real country anymore. My fans are still loyal, though. So when I have a new record, it doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad; I know I’ve got so many that’s going to sell. And if I come out with a great record, then people who don’t know of me will go out and buy it. That didn’t used to happen, which means that country music is getting more like the pop field: you’re only as good as your last record. What I don’t like is turning on the radio and not being able to tell whether I’m listening to a country station or a pop station. I like the good sound of modern country music, but I also hope our music won’t lose its identity.

How do you tell what’s country and what isn’t?

By how a record is cut and by what chords are used. When you start having too many minors and too many horns, I think you have to check it out. I also think it doesn’t hurt to have a little bit of the good old fiddles and banjos and mandolins on your records. When I started singing, country music was real country. Today, pop has gotten a little bit more of a country sound, and country has gone a little more pop. They’re meeting, but there’s still a lot of difference between them.

Country music’s always been a little, wrapped-up world of its own, but it’s really been changing fast. When I came to Nashville, country music wasn’t on television and there were no big award shows. And if anybody got an award, it was from a trade magazine like Billboard or Cashbox or Record World, and it was a smallscale thing. Now it’s all on a big scale, because country music has become a multi-million-dollar business. And you can see it most in Nashville. There’s a bunch of new hotels and motels, two country wax museums, the Country Music Hall of Fame, and the new Grand Ole Opry in Countryland, which is probably as big an amusement park as Disneyland.

A lot of that change was chronicled in Nashville, the Robert Altman film in which Ronee Blakely played a country singer modeled closely after you. Was it painful to watch her character undergoing nervous breakdowns, knowing all the while that reviewers would inevitably write about your own bouts with depression throughout your career?

Well, when the movie first came out, I’d just had a real bad spell with my nerves, and Nashville people-who didn’t like the movie-asked me not to see it. So I didn’t. A year later, though, I was working in Las Vegas and saw Nashville on television-and I enjoyed the devil out of it. Just about all the country music people I know were upset by that movie, but I think there was a lot of truth in it.

What kinds of problems had you been having?

I’d just changed agencies, and the old agency had taken me to court, and it was a long, drawn-out legal thing, and I was taking a few too many nerve pillsValium and sleeping pills. People would say, “Are you on uppers?” And I’d say, “No, who wants to stay awake?” I wanted to sleep; that was my problem.

Because of the lawsuit?

Yeah, and I’d never taken a nerve pill in my life till I went up to the witness stand. A couple of years later, I really started taking nerve pills to escape a problem. At the time, I was getting a lot of threatening phone calls. People would call up sayin’ they were going to take my kids or kidnap me, and then it got real serious after a certain bad experience.

What happened?

Well, a little 21-year-old guy with long, blond hair had been following me around on the road for a week, and every time I’d go out to get ice for my husband-Dao was with me on the trip-the boy would be standing outside, smiling at me. I remember telling my husband, “Gee, I have got a true fan.” The next day, we were playing a town in West Virginia, and when I came out of our bus to go onstage, I realized I had forgotten my slip, and I’m very funny about being afraid somebody’s going to see through my dress. I sent somebody back to the bus for my slip, and I was about to put it on backstage when this hippie-lookin’ girl staggered up to me. I thought she was drunk-I’d never really seen anybody on dope, so I didn’t know what she was on-and she said she had some songs she wanted me to hear. Police were standing all around, because I’d asked for protection ever since I’d been getting all these crank calls.

The girl asked if she could see me alone in the back of the bus because she didn’t want anybody else but me to see her songs. She’d no more asked her question when the police grabbed her by the hair and dragged her away; and when they got her over to the door, they threw her out. I didn’t know if they’d killed her or not, and I don’t really think they cared. I went onstage thinking, “My God, what have they done to that poor little thing, and why is this going on?”

Well, it turned out that the blond guy who was following me had asked the girl to get me alone because he hadn’t been able to do that himself. It turned out that he’d killed two people and had robbed my Western store. The cops had gotten a lead on him from the robbery, and they’d been following him-and he’d been following me. One day I asked the cops why he wanted to get me alone, and they said, “Do you really want to know?” I said no, because it sounded like it was really bad. For about a year after that I was way down and depressed. Penthouse: Was that totally attributable to your brush with danger?

I think everything just piled up. I was working so hard, and when I first started singing-me and my husband had talked, and we thought I’d only work hard for two or three years and then we’d be rich and I’d get out of the business. But it didn’t happen that way. I really needed to be with my first boy when he was growing up, but I was always on the road, and I missed him all the time. Then I got pregnant with the twins, and I kept right on going, and when I looked around, they were just about grown.

Meanwhile, the more I worked, the more I made, the more we spent, and the more payments I had to keep up. I think I really got angry toward life and real bitter, and that’s when I let it get me down. If people want to know the truth, that’s it.

Will that part of your life be depicted in Coal Miner’s Daughter, the film version of your autobiography?

I expect it will be. I think there’s going to be things in that movie I’m not going to like, but it’ll probably shape up my whole act by showing me things I do that I don’t like. I mean, maybe I’ll straighten out things I don’t like about myself and haven’t even realized I’ve been doing. That movie will probably be a great lesson for me.

Cissy Spacek stars in the title role of Coal Miner’s Daughter, and, without having seen the film, a number of Hollywood insiders feel she may have been miscast. Do you share that opinion?

No, ’cause I was the one who picked her. After the book came out, I knew there was going to be a movie, and I offered it to Universal first, because they own the label I record on, MCA Records, and I wanted to keep it all at home.

About six months later they came to me and asked who I wanted to play the title role, and I hadn’t even given it a thought. Pretty soon after that I was handed a stack of eight-by-ten glossies of actresses, and a bunch of ’em were pretty big names, and some of ’em looked a lot more like me than Cissy does. But when I saw her picture in that stack, I just stopped. It was a glamour picture of this blonde-haired girl with freckles, and I said, “This girl here, she’s the one to be in the movie.” They didn’t want to use somebody who was blonde and fair and freckled, but I just said, “So what? That’s who I want.”

Later on, I tried to find out more about Cissy. So Universal showed me Carrie. I wanted to see if she could get exactly what I wanted her to get as me. If there was supposed to be love or hurt in my eyes, she would have to be able to show it, and with feeling. After seeing her in Carrie, I knew she had it all, and I never doubted her for one minute. Once they started shooting the movie, I was asked to come on the set. They’d say, “Aren’t you curious about what she’s doing?” And I’d say, “No, she’s me.” She is me.

You know, the very first time I started working with her on the songs, I began singing one little song for her, and then Cissy took over and sang the rest just the way I once had. There was the same little break in her voice that there had been in mine. That was the first song I’d ever sung in public, and there’s just no way in the world that girl could have known how

I’d sung it. Really, it was as if her mind took over my mind.

Did you relive your life at all while the film was being shot?

Oh, did I! I only watched them work once, when they asked me to go to Kentucky to help draw a crowd for a state-fair scene. It was dark when our bus got to the hotel, and the movie people asked me if I’d like to drive up to where they were shooting .a night scene involving Butcher Hollow, where I grew up. I said yes, and we got there at about ten o’clock that evening.

The whole thing turned out to be weird. For some reason I thought I was going to see Cissy sing “In the Pines,” but when we got close to this old house, I couldn’t hear nobody singing. I guess I kind of freaked out from being so near to my old home, because when I got up close to the house, I seen this old man settin’ on the porch and I was sure it was my daddy.

They’d told me that Levon Helm, who plays Daddy in the movie, was in the hospital and that they couldn’t film him that week. So when I saw this guy, I started thinking it was Daddy. It was foggy and dark, and little frogs were chirping, like they always did in Butcher Holler, and my mind started drifting back-and my God, I really believed I was seeing Daddy. I even looked over at Owen Bradley, my record producer, and said, “There’s Daddy.” I guess I started acting stupid, and everybody figured they’d better try to do something about it. Cissy was standing in front of me and grabbed me and said, “Loretta, I’m Cissy. Have you forgot me?” I just said, “But I see Daddy up there.”

About that time Tommy Lee Jones, who plays Doo, walked out on the porch and said, “Mr. Webb, me and Loretta want to get married, and we want to ask you what you think.” That brought me out of it. My mind was playing weird tricks on me, I guess. It was a terrible thing. Leon Helm had just gotten out of the hospital that day, and he looked like Daddy and acted like Daddy, and it was like Daddy just took over his body.

Have you ever had experiences similar to that one?

Well, I believe in reincarnation, and I believe I’ve lived other lives in the past. And I’ve experienced those lives. Have you ever been hypnotized?

No, we haven’t.

Well, I hadn’t been either, and I always said I couldn’t be. A couple of years ago somebody tried to hypnotize me, and I remember saying to myself, “Boy, I’m sure fooling this man. I’m really going to put him on.” I lay down for 15 or 20 minutes-and when I listened to the tapes, it turned out I’d been hypnotized for more than two hours, and he’d put me back into lives I’d lived in the past.

Such as?

Well, according to these tapes, the last life I lived was as a man in New York City, and I died there in 1928. It started out with me in a baby carriage, and then, later on, I was working in a restaurant and paying my way through a college in New York. I didn’t finish college because I had to support my wife. I died real young, probably of a heart attack. After that, I had the flashback of being married to a very old man, probably in Ireland, and I looked very much the way I do today, except I was a little bit taller and had on a dirty old cotton dress. This old husband of mine was confined to bed, and I was feeding him potato soup, and my kids were running around dirty, and we lived in the country.

I had one more flashback with the hypnotist in which I was a servant, bringing out platters of food to a bunch of men. And when the hypnotist asked me who my master was, I said, “He’s the king.” He asked me my master’s name, and I said that it was King George and that I was his girl friend on the side-the queen didn’t know about it. I told the hypnotist I lived near a village called Claridge and that I was very unhappy, because the king was going to be killed. Meanwhile, the king’s best friend was grabbin’ me and making love to me behind the king’s back, and I was afraid to tell the king about it because they were such buddies. Anyway, the king died before I did, and then his best friend choked me to death.

I read up on this a little, and there were six King Georges, and I’m pretty sure I was involved with the second one.

Do you really believe these things actually happened to you?

I really do, yes. The strongest of all these past lives came to me when I was alone in the back of my bus, in a kind of trance. I’d been reading the Bible when I suddenly started having a flashback of an Indian thing. I was standing next to my husband, who was mounted on a horse, and we were on a kind of rolling hill that was just packed with Indians on horseback. They weren’t all dressed alikesome had loincloths; some didn’t-and they wore their hair in different ways, and they were all painted different. I remember I was wearing a buckskin shirt, and I was kinda sloppy-looking: I was saying good-bye to my husband, and he was the only one wearing a war bonnet. He was the chief.

How real did this seem to you?

As real as it is right now, sitting here and seeing you. They were all going into battle, and I was saying good-bye to my husband, and it was a real touching moment for us. Behind me, I could hear lots of kids running around and playing, and when I looked back I saw a whole valley of tepees. All of a sudden a shot rang out, and my husband slumped over dead. I started screaming and ran back to our tepee, and I was yelling at the kids to run to safety and that’s when I came out of it. I remember thinking, “Goodness, I hope nobody heard me screaming like that.”

Did you try to find out more about that particular experience?

I surely did. Lorene Allen, my office manager, told me about this woman, Kathy Hughes, a Nashville psychic, and so one night we went to a seance over at Kathy’s house. We hadn’t told anyone about that flashback, and the seance started very soon after we walked in. Spirits supposedly would come in, and the table would raise a little and bang down once for “A” and twice for “B,” and so on. Anyway, we found out that my Indian name had been Moonflower and that I’d been married to a chief.

I asked the spirit, “How did my husband die?” and it was spelled out that he was shot before going into battle. I was told I was 39 when I died and that I had nine kids, but only six of ’em had lived.

You’re sure this psychic had no prior knowledge of what you’d experienced?

I’m sure, and if you really want to hear something, listen to this. About three years later, I was talking to this 68-yearold guy from Oklahoma. He telephoned me and said he’d been studying reincarnation and that he’d been married to me in one of my past lives. Well, I thought he had to be some kinda clown, and I didn’t even give him the benefit of the doubt. He said he and his wife were coming to see me in Tennessee and that he wanted to show me some studies he’d made in the last few years. And as you can well imagine, I just thought, “Oh, sure.”

Well, one day he and his wife turned up at our house, and my husband figured they were fans who I knew; if Doo had known they were there to talk about reincarnation, I’m sure he would’ve run them off. Anyway, the guy had a stack of photographs, and he showed me one of ’em that was him and me as Indians.

Did it look like you?

No, I didn’t recognize it at all. But we started talking, and when I asked him how he died back then, he told me that just before going into battle he’d been shot to death by the half-breed him and me had taken in and raised as a son. He said the boy had fallen in love with me and had snot him from a distance because he didn’t want anyone to know who did it. I asked him how many kids we had, and he said nine, but that three had died. I started getting a little edgy right around then, and when I asked him what he’d been, he told me an Indian chief.

Now this was just a good old country boy from Oklahoma City, and I didn’t doubt his honesty. I really don’t know what I conclude from all this except that some of it is funny and some of it is weird-and I believe it. Whew, we sure got sidetracked, didn’t we?

With all these other lives on your mind, have you decided what you intend to do with the rest of this one?

First thing I’m gonna do is slow down. You know, I used to get really upset with my husband because he’d always say, “I sure wish you could stay home,” but he never done nothin’ about it. Pretty soon I had an agency, some publishing companies, our ranch. I had a rodeo for ten years-I had my fingers in too many pies. I’d say, “Honey, I want to slow down next year,” and then I’d read newspaper interviews with my husband where he’d say, “Well, I’ve tried to get her to slow down for the last ten years, but she just won’t do it.”

That wasn’t true?

No, it wasn’t. Sure, he would’ve liked me to stay home, but I always felt he ought to have been trying to tie up some loose ends so I could stay home. I always hoped he’d be preparing for it, ’cause when you’ve got 100 people working for you, it’s hard to just turn around and tell them that next week they won’t get paid. So I started thinking, “Where does it end? When am I going to slow down?” I didn’t see no stopping point, and meanwhile everything just got bigger and bigger. I’m not gonna be two-faced about this and tell you I don’t enjoy what I’m doing, ’cause I do. But I kinda think I’d just like to do about six weeks a year on the road arid that’s all.

In his Penthouse interview, Merle Haggard told us that as soon as he’s home for more than three days he feels the need to take off again. Do you think the same thing might apply to you?

Well, Merle might have somethin’ there, because being on the road is kind of an escape. The other day in Las Vegas I mentioned to somebody that I got married at 13 and that I’m still married to the same ale boy. I was asked what’s kept us· together· all these years, and I said, “Bein’ apart.” I really think that has a lot to do with it, because if I was gone only a couple of days a month, it would give me and Dao an awful lot of time to quarrel. I think being away so much. has kept things fresh and new for us, and I think you have to have that.

What do you think you’d do if you were home all the time?

Well, when I go home now I work real hard. I put out the garden and the flowers, I work in our gift shop, and I also get involved in our dude ranch. I’ll tell you, a woman’s got a full-time job just stayin’ home and taking care of the house and the kids; and if she’s doing that I don’t understand why so many of ’em get hung up on nerve pills and television soap operas.

For myself, now that my kids have all grown up, if me and my husband was farming, I know I’d be workin’ all the time. But still, it might get boring if I was sittin’ home all the time. I’m really fightin’ about it with myself right now, because I know it’s coming and I just have to be prepared to face it. And I’m very serious about it. But in another way, I wonder what it’ll be like. I guess it’s all up to me to find out, isn’t it?