The almost unbelievable story of the love-death relationship of Sid Vicious and his girlfriend Nancy Spungen — as witnessed by the victim’s mother.

Love Me, Kill Me

“There’s really a lot goin’ on here, Mom. Music. People. I’m meeting a lot of people.” It was a transatlantic phone call from my twenty-year-old daughter, Nancy. In spring of 1976 she had gone to London to visit. She had just spent a traumatic eighteen month away from home, living in New York City, where she has hung out in the rock music scene — her first love — and taken too many drugs, including heroin. Nancy had been emotionally disturbed since birth. She had spent over one fifth of her life in a school for disturbed children. She also has been committed for brief periods to several mental institutions. For years my husband, Frank and I had little control over her. Visits with too many psychiatrists had not helped. In the end, there was nothing to be done but let Nancy go, let her lead her own life.

“You know who I met at a party last night?” she continued excitedly. “You won’t believe it.”

“Who?”

“Sid Vicious!”

“Who?

“Sid Vicious.”

“Who is he?”

“A punk rocker. He’s with the Sex Pistols, Mom.”

“Who are the Sex Pistols?”

“They’re the biggest band in England. They’re great. The Best.”

“Oh.”

“He’s nice. Really nice. I really like him. I think he likes me, too”

“What kind of name is that, Sid Vicious?”

“I met Johnny, too”

“Johnny?”

“Johnny Rotten. The singer.”

“He’s with the Sex Pistols, too?”

“Uh-huh”

“That’s very nice.” I had learned long ago not to cross Nancy. My objections had not impact on her. In fact, they only served to fuel her ever present anger.

I paid no further attention at that time to the subject of punk music or the musician Sid Vicious. I assumed he was just another of her fleeting attachments. There was no reason then to think otherwise.

Within two weeks Nancy was, it appeared, back on heroin. She denied it, but on the phone her voice was slurred. She was paranoid and didn’t make a lot of sense. And she was out of money.

“I can’t stay with my friends no more, Mom. They don’t like me. Don’t want me there. They hate me.”

“So where are you staying?”

“On the street. In a car. Your Nancy’s sleepin’ in a car. And I got no food. Nothing to eat. No money, Mom.”

“You’re back on.”

“No, it isn’t that.”

“Nancy, don’t lie to me.”

“I’m not. ”

“You told me never to trust a junkie.”

“I’m your daughter.”

“Even my daughter.”

“I’m not on junk. I swear. It’s just that… that nobody likes me. And I’m sleepin’ in a car. No place. No food. I need money, please. The money from my certificate. Send me some of it. There’s a thousand left, isn’t there? Please, Mom. Please.”

“Maybe you should think about coming home.”

“No! I won’t! I’m not ready!”

“But you’re not hacking it over there.”

“I’m okay. I just need money. I just need… I need spring. It’s so cold here.”

I told her I’d have to think about it.

I agonized over it. I felt more helpless than ever before. She was so vulnerable, so incapable of taking care of herself. And so far away.

As far as I know, she had no regular place to live until midsummer, when she phoned to inform me that she and Sid were moving in with his mother.

“Sid?” I asked, not placing the name. “From the Sex Pistols, Mom. Sid Vicious. He’s the biggest rock star in the world. And he’s all mine. Isn’t that great?”

“So you two are…?”

“We’ve been crashing at people’s flats for a couple of weeks but it’s no good.”

I heard a man’s voice in the background.

Then Nancy said, “Here, Mom. Sid wants to say something.”

There was a rustling and a man with a heavy English accent said, “Hello, Mum.”

“Hello, Sid,” I said.

“How are ya?” He had a flat, placid-sounding voice.

“Fine. How are you?”

“Fine. Your daughter looks so pretty. I bought her shoes.”

“That’s nice.”

“And fancy underwear.”

“That’s very nice, Sid,” I said. “Sid?”

“Yes, Mum?”

“Could I speak to Nancy again?”

“Yeah, sure. Okay. But could you send us money? For Nancy?”

“I’ll talk to her about that.”

“Oh, okay. Here’s Nancy. Nice talking to you, Mum.”

“Nice talking to you, Sid.”

“Bye, Mum.”

“Good-bye, Sid.”

Nancy got back on. “Isn’t he great?”

“He sounds very pleasant.”

“Oh, he is. He’s a very nice lad, Mum.” Nancy was starting to pick up an English accent.

“With that name,” I said, “you’d expect he’d be, I don’t know, kind of rough.”

“Oh, no. That’s just for the act. He’s nothing like what the papers say. That’s all made up. Would your daughter go out with someone like that?”

I decided then and there to find out what the papers said about the Sex Pistols.

“Is he on heroin?”

“No.”

“Are you?”

“Yeah, but I’m going on meth again. Sid wants me to. See how good he is. Can you send me some money? So we can get settled? Sid’s broke, too.”

“If he’s such a big success why doesn’t he have any money?”

“I think they’re holding out on him.”

I told her I’d think about it. I ended up sending her fifty dollars.

The Sex Pistols’ first album, Anarchy in the UK., was released in England in November 1976. The group first came to the attention of the mainstream British public a few days after its release because of an appearance on a national television talk show. Its host, Bill Grundy, asked them to say something outrageous to the viewing public. They obliged by letting loose with a string of snarled obscenities, resulting in front-page news the next day, as well as the suspension of Grundy.

By the time Nancy arrived in London four months later, the Sex Pistols were the biggest sensation in England.

It was only natural that she would like the Sex Pistols, want to be involved with them. They were angry and violent. They were the newest thing on the musical horizon, the next step past the underground New York punk scene. They were celebrities. Later, when she herself would become a punk celebrity, journalists would characterize her as a girl who took to punk because it was a repudiation of middle-class life. Not so. Nancy loved being middle-class. She was making no social statement. It was simply the music that attracted Nancy to punk. Always, it was the music. It was her flame. All she wanted was to get close to it. As close as possible.

Nancy and Sid stayed with his mother for less than two months. She and Nancy apparently didn’t get along. So Nancy and Sid moved into a hotel. Nancy phoned me from her new place of residence. From her calls, I learned that she was becoming exposed to the violence that surrounded the Sex Pistols.

“I got beat up, Mom,” she moaned. “My nose is broke somethin’ ‘orrible. It’s all over my face. It hurts.”

“Who did it?” I asked.

“The Teddys. They don’t like us.”

“Who are the Teddys?”

“Assholes who hate punks. They attacked us on the street. They gave me two black eyes, too. Sid got knifed. But we’re okay. And I’ll be ready for ‘em next time. Sid bought me a truncheon.”

Two weeks later she phoned to say she and Sid had moved to a different hotel. When I asked why, she replied that the manager of the hotel had asked them to leave.

“Sid got mad,” she explained, “and dangled me out the window. I was screaming at him to let me back in and I guess it pissed off the people in the hotel.”

“Are you okay?” I asked. What else could I say?

“Oh, yeah. It was nothing. He was just upset.”

They got into another reportedly violent quarrel in a different London hotel room at the end of November. Again, Nancy’s screams brought the manager. This time the British press was also alerted. The papers reported that the manager went up to Nancy and Sid’s room to find a blood-stained bed, a near-naked Sid bleeding from cuts on his arms, and broken glass all over the carpet. There was a bottle of pills on the nightstand. A police inquiry was launched.

A second problem also arose to doom Nancy and Sid’s life together: Sid’s career. The Sex Pistols were an overpromoted, talentless outfit, and after the novelty of their outrageousness had worn thin, the group disbanded. Sid tried a solo act in London. He cut a single called “My Way,” but it failed to take off.

“I’m managing Sid’s career now, Mum,” Nancy told me over the phone. “He’s gonna be even bigger as a solo. He’ll do better in the States, I figure,” she declared firmly. “So we’re comin’ back for good. End of August or so. As soon as we get to New York, I’ll bring Sid down to meet the whole family. We’ll stay for a while. Won’t that be great?”

Nancy was coming home.

The prospect stirred bad memories. Not memories of the public Nancy, the punk Nancy, but memories of our private Nancy, the one we’d grown up with. That experience was far more frightening than anything I’d ever read about the punks.

Frank and I were at the Trenton, N.J., station when the train pulled in. Commuters spilled out of the doors and shoved their way across the platform to the escalators. I craned my neck in search of my Nancy. I couldn’t spot her.

Then the air was pierced by “Mum!”

It was Nancy’s voice. My eyes sought her out and found her.

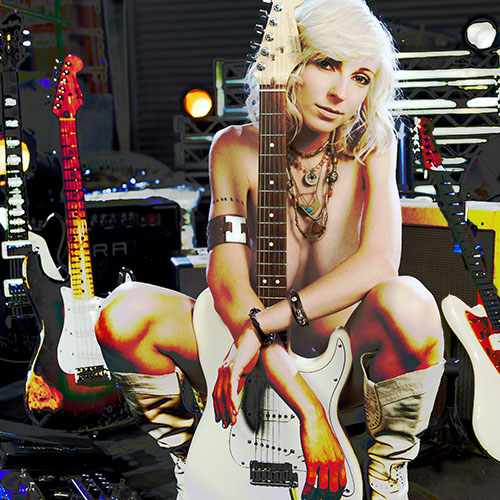

I was not prepared for how much she’d deteriorated — even from when I’d seen her on TV. She looked like a Holocaust victim. She was much thinner. Her skin was a translucent bluish white. Her eyes had sunk deep into their sockets and had black circles under them. Her hair was bleached white, and along the hairline there were yellowish bruises and sores and scabs. She wore a black leather jacket with a torn, filthy T-shirt under it, tight black jeans, and spiked heels. Around her neck was a charm necklace-silver charms of gargoyles and snakes.

She looked like the walking dead. Behind her lurked Sid. I say “lurked” because he was at least a foot taller than her, and his spiky hair stood straight up on his head. He, too, was bluish white and painfully thin. He wore a black leather jacket, black jeans, black motorcycle boots, and a matching black leather collar and cuffs with pointed metal studs.

Frank and I just stood there, gaping at them. We weren’t alone. Everyone, but everyone, on the platform was staring at them. They stood out as much as if they’d just arrived from another planet. There was a total absence of life to them. It was as if the rest of the world were in color and they were in black and white.

They were totally oblivious of the scene they were causing.

Nancy came toward me and I toward her. We met halfway and embraced.

“My mum!” she cried as she held me tight. “My mum.”

But it wasn’t my Nancy I held in my arms. I felt as if I were holding a stranger. I wanted my Nancy back. But my Nancy was gone. A sob welled up in my throat.

“Mum,” she said, “this is Sid. Sid, this is my mum. Isn’t she beautiful? Just like I told you.”

He stuck out his hand. I shook it. It was wet and limp, a boy’s hand. He was a boy, shy and more than a little confused by the strange surroundings.

“‘Allo, Mum,” he said quietly.

“Hello, Sid,” I said.

He wasn’t so evil-looking once you got used to the sight of him. It was partly his drooping eye that made him appear so malevolent. His presence, however, was not malevolent. It was subdued. My impression was that he simply wasn’t very bright.

At home I barbecued a steak and served it with corn on the cob, salad, and garlic toast. We ate outside on the patio, under our green-and-white-striped awning, seated around our glass-topped wrought-iron table with its six matching wrought-iron chairs.

Nancy’s teenage brother, David, and sister, Suzy, watched as she cut Sid’s meat for him. Apparently Nancy always did. Then he dug in. He ate ravenously for a few minutes, his face in his plate.

“Fuckin’ good food,” he said. “Fuckin’ good, Debbie. Never have I had a meal like this. Never. Used to be I lived in a place with rats. Had to tie the food up in bags. High up, so they couldn’t get at it. Never have I had a meal like this.”

“I don’t cook much,” Nancy giggled.

“But that’s okay,” he said. “She’s so fuckin’ good to me.”

“That’s very nice,” I said.

We ate in silence for a moment.

“So what are your plans?” Frank said.

“We’re at the Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan for now,” Nancy said. “We’re gonna get a flat. I thought I’d see if my old one is empty. Our stuff is on the way. Our sofa and clippings and Sid’s gold record and his knives and… ”

“Knives?” I asked uneasily.

“Wish I had me knives,” Sid lamented. “Never know when you might get cut. That’s how I got this eye. In a fight.”

“Once we get settled, I’m gonna promote my Sid,” she said. “I’m his manager now. I’m a professional. Oh, I’ll have to show you my portfolio after dinner! I’m a star! Can you believe it? I made it!”

We smiled and continued to eat.

“Oh, and we have to find a methadone clinic in New York. We brought some back, but it’ll run out pretty soon. You know how we got it past customs?”

“No,” I said.

“ I poured it in a bottle of dish soap. Fairy Lotion, it’s called. They didn’t think to look in it. Wasn’t that stupid of them? I knew they wouldn’t. They’re so unbelievably dumb.” She lit another cigarette. “So, Suzy, how are you doing, love? You moved into the city?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Like it?”

“Uh-huh.”

“That’s grand. Just grand. And David? You’re in private school?”

“Yeah, that’s right.”

“Sid wants to play,” Nancy said. “David, do you still have your guitar?”

“Yeah,” he said. “I’ll get it.” He went inside to get the guitar from his bedroom.

“Do you know our music, then?” Sid asked us.

We nodded.

“Do you like it?”

We nodded yes.

David returned with the guitar, handed it to Sid.

“Let’s go in the den, Sid,” Nancy said. They grabbed their cigarettes and got up.

“Best fuckin’ food I ever ate,” Sid said.

“Thank you, Sid,” I said.

“Debbie?”

“Yes, Sid?”

“Is ‘Sha Na Na’ on? On the telly?”

“Do you mean right now?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“They’re on tomorrow, Sid,” David told him. “Saturdays at seven.”

“Oh,” Sid said. “Don’t want to miss ‘Sha Na Na.’ They’re my favorites.”

He and Nancy went inside.

The four of us ate our food in silence, glancing occasionally at the remains on Nancy’s and Sid’s plates.

“Come inside!” called Nancy. “Come in and hear Sid play!”

We went inside to hear Sid play. He and Nancy sat close to each other on the sofa.

“Sid has something he wants to show you,” Nancy said. “Okay, Sid. Go ahead.”

Sid proceeded to bang out two chords, clumsily and with great difficulty. Then he stopped and looked up, grinning crookedly. That was it. That was what he wanted to show us. Our cat could have played it.

The four of us just stood there, staring at the two of them.

“Ain’t that great?” asked Nancy.

We agreed it was great.

Nancy looked to Sid for support, but he had begun to melt into the sofa, half asleep.

“Perhaps,” I suggested, “I should take you to the hotel.”

“Okay,” Nancy said. “No, wait. You haven’t seen my portfolio yet. You have to see my portfolio.”

She jumped up and went to the foyer to get it. Then she came back and cleared a spot on the coffee table. We gathered around the table to be shown her portfolio. Sid perked up, sort of.

Her portfolio was actually a scrapbook in which she had pasted newspaper photos and stories about herself and Sid as we1·1 as publicity shots of the two of them.

“Don’t I look beautiful in this one?” she asked.

In it, she was by Sid’s side, one fist clenched at the camera, teeth digging into her lip. Sid was shirtless and snarling.

“So beautiful,” Sid agreed, putting his arm around her proudly.

“It was taken at a press conference,” she said. “The photographer told me I could be a model if I wanted.”

She looked half dead in the picture. The statement was so pathetic I winced.

“I bought her those shoes,” Sid pointed out. “I bought her everything she ever had.”

She showed us the other pictures in her portfolio. Some of them predated Sid. There was the photograph of her with Debbie Harry, a picture of our cats, a picture of her friend Sable.

I again suggested taking them to the hotel. Sid said he’d like that. I drove them while Frank, Suzy, and David cleaned up.

Nancy positioned Sid in the backseat, where he immediately began to doze. Then she joined me up in front.

“Great to be back, Mum,” she said as I pulled out of the driveway.

“Nice to have you.”

“Hated the bloody weather in England. Damp. House looks nice.”

“Thank you.”

“How come you have sliding glass doors in the kitchen now?”

“It’s easier.”

We drove in silence for a while.

“So when are you going back to New York?” I asked.

“Sunday night. That okay?”

“Fine.”

“We have to find a methadone clinic on Monday.”

We said nothing the rest of the way to the Holiday Inn. We really had nothing to say to each other.

Nancy and Sid were dependent on each other. They cared for each other. To them, what they had together was genuine love. It was the only time for Nancy. Sid was the one great love of her life. She was twenty years old, he a year older. They were basically the same age Frank and I had been when she’d been born. That was hard for me to imagine. They seemed like children to me, immature and incapable of taking care of themselves-much less another human being.

I tossed and turned the entire night.

Happily, it was bright and sunny the next morning. I phoned at noon and woke them up. Nancy asked me to call back in an hour. I did and woke them again.

“We’ll get up,” Nancy said. “Come for us in an hour.”

David picked them up. They weren’t in the lobby when he got there, he later informed me. So up he went up to their room and knocked on the door. Nancy called for him to come in. They were still in bed, naked, watching Saturday morning cartoons. When David walked in they got out of bed, put on their rumpled clothes from the previous night, and took a swig each of methadone from the Fairy Lotion bottle. Then Nancy said, “Let’s go.” Neither of them got washed or brushed their teeth.

At our place the two of them stretched out in the sun on lounge chairs. Suzy had made plans to visit a friend, so she left. Frank, David, and I had lunch on the patio. Nancy and Sid said they weren’t hungry.

He was green after five minutes in the sun.

“I don’t feel very well,” he said weakly.

“He’s probably not used to the sun, Nancy,” I said. “Maybe he should sit in the shade.”

She helped Sid move to a chair in the shade. When he still felt ill, I suggested she take him inside where it was air-conditioned.

“Stretch out on the sofa in the den, Sid,” Frank said.

“May I watch the telly?” Sid asked.

“Sure,” Frank said.

“Any cartoons on, Frank?”

“Don’t know. Probably.”

“How about ‘Sha Na Na’? Is it on?” “Tonight, Sid,” David said. “At seven.”

Nancy took him inside, laid a towel down on the sofa to protect against his wet suit. He stretched out. When I came inside she was sitting on the end of the sofa, stroking his head, which was in her lap.

“How does he feel?” I asked her.

“A little better,” she replied.

“Does he want something cold? Sid, would you like a drink? A cold drink?”

“Please, Mum.”

I brought him some juice. He thanked me and drank it. Then he sat up and lit a cigarette. Nancy turned on the TV and found some cartoons for them to watch.

They sat there on the sofa for the remainder of the afternoon, chain smoking, staring at the TV, glassy-eyed. They seemed stuporous. Occasionally they would nod off, lit cigarettes in hand.

I went into the kitchen — stomach knotted, teeth clenched — to find something to do. I couldn’t sit there anymore looking at the two of them.

There was no point in saying anything to her. I couldn’t reach her. She was lost to me. My arms ached to hold the baby Nancy, ached for a fresh start.

I didn’t know how much longer I could stand it. I wanted them gone.

Suddenly Nancy appeared behind me.

“Mum, would you take me to the hospital?” she asked.

“What for?” I demanded, alarmed.

“I, uh, got beat up by the Teddys a few weeks ago and they pulled my ear off. A doctor sewed it back on, you know, but I forgot to get the stitches out. Just remembered.”

“Here, let me see,” I said.

She pulled back her hair and turned so I could get a good look. First, I noticed the yellowish bruises and open sores along her hairline. Then I saw the ear. Revulsion swept over me as I saw the row of stitches that ran along the back of her ear, all the way from the top, where the ear met the skull, to the bottom, where it joined the neck.

It did, however, look clean and healed.

“We’ll have an awfully long wait at the hospital,” I said.

Not to mention another scene.

“How about your doctor, Mum?”

“It’s Saturday. He’s off. Tell you what, I can take them out. There’s nothing to it.”

“Okay.”

I went upstairs to fetch a pair of small scissors. I washed them in alcohol, took them downstairs with the bottle of alcohol, some cotton, and antibiotic ointment. Nancy was waiting for me in the kitchen.

“Stand next to the window,” I said. “The light is better.”

She obeyed.

“Okay, now don’t move,” I said.

“I won’t.”

She stood perfectly still for me as I cut the little catgut knots one by one and pulled the stitches out. I worked smoothly and calmly, as if I took out stitches every day. In actuality, I had never done it before. When I was done, I cleaned the ear and put ointment on it.

“It looks fine,” I said.

“Thanks, Mum. Could you make an appointment with a plastic surgeon? These scars all over my arms. I’d like to get ‘em off.”

“We’ll see,” I said.

I sensed another presence in the room. I turned to find Sid looming in the doorway.

“Mum,” he said, “I need a doctor for me eye. It won’t stay open. Could you make me an appointment, too?”

I looked at her, then at him. I felt myself getting sucked into their universe. Now there were two of these helpless souls for me to take care of. My burden was doubled. I took a deep breath, let it out.

“I’ll try, Sid,” I said.

“Thank you. That’d be very nice of you. don’t like my eye, you know. I got it in a fight. People always want to fight with me. Teachers. Policemen. Teddys. Everybody. I don’t want to, but they do.”

“He’s really a very sweet lad, Mum,” Nancy said.

They returned to the sofa and began to nod off again.

When it got to be about six, I went into the kitchen to set the table for the four of us. Nancy and Sid would eat in the den before the TV. Suzy followed me in there. She was angry.

“How can you stand this!” she demanded. “How can you watch them? How can you watch her dying like that? Why don’t you do something?”

I wanted to say, “Suzy, if I let myself react at all, my head will simply blow right off.” But I didn’t want her to know I was so upset. And I was too upset to explain myself. I shut her out. I shouldn’t have, but I did.

“They’ll be gone tomorrow,” I said. “Let’s just get through the weekend.”

She glared at me. “I don’t see how you can put up with it. Your own daughter.” Then she stormed out.

After dinner the four of us, ever alert to the falling cigarette ashes, watched the two of them nodding off on the sofa.

Suzy was still angry. She glared at her sister with a combination of curiosity and disgust. Nancy caught her.

“If you look at me like that one more time I’ll cut your fucking face up,” she snapped viciously, her eyes cold.

Suzy froze. There was total silence. I couldn’t stand the tension in the room, so I went into the kitchen. Suzy followed me in there, wide-eyed.

“Do you think she will?” Suzy whispered, terrified.

“I don’t know,” I replied. “I don’t know.”

Suzy went up to her room. She was so scared she went back to her apartment in the morning, before Nancy and Sid came back from the hotel. Suzy never had the chance to see or speak to her sister again. That little scene they’d played out in the den was their final communication.

Frank took them to the hotel that night. I picked them up on Sunday at about one o’clock. Just as David had the day before, I found them naked in bed. They got up, pulled on their now filthy clothes, gulped their methadone, and were set to go.

“Don’t you want to pack?” I asked, wary that they’d changed their plans and were going to stay longer.

“Oh, right,” remembered Nancy, heaving their few possessions carelessly into an overnight bag. “All set, Mum.”

I checked them out of their room and we drove them to the station. Frank and I got in the front seat, David in the backseat with Nancy and Sid. Nancy said nothing in regard to Suzy’s absence, though she did clutch her sister’s offering of chocolate chip cookies.

“Thank you so much for having me,” Sid said.

“Our pleasure, Sid,” Frank said.

We drove in silence for a while. Then out of nowhere, Nancy quietly said, “I’m going to die very soon. Before my twenty-first birthday. I won’t live to be twenty-one. I’m never gonna be old. I don’t wanna ever be ugly and old. I’m an old lady now anyhow. I’m eighty. There’s nothing left. I’ve already lived a whole lifetime. I’m going out. In a blaze of glory.”

Then she was quiet.

Her words just lay there like a bombshell. No one wanted to touch them. She hadn’t issued a threat, simply made a flat statement. We all believed her. Even Sid.

Nancy lived out her rock fantasy in New York, sharing the bed and the career of a star. But she and Sid were running out of time.

Nancy did manage to find them a methadone center, but the lines were long and every day Sid was taunted by the other addicts. He got mad. He got in fights.

“They keep hasslin’ my Sid,” Nancy reported. “He’s got this hot button, Mum, and they just won’t leave it alone.”

She went to work on Sid’s career. She tried to line up recording contracts for him, but found little interest from the record companies. Sid had no actual career. All he had was a claim to fame. But neither she nor Sid realized that.

“It’s not workin’ out,” she told me over the phone. “Nothing’s happening. Sid’s real depressed.”

They went back on heroin, and sank deeper into despair. I spoke to her about once a week and each time she sounded lower. She and Sid went out of their room at the Chelsea less and less. One night one of them nodded off in bed with a lit cigarette and set the mattress on fire. Reportedly, a hotel employee rushed up to their room with a fire extinguisher to find them wandering around, oblivious of the smoldering mattress. The manager moved them to another room, room 100.

Nancy called once to say she was ill.

“I’m sick,” she said weakly. “My kidneys. I’m sick from my kidneys. Can you send money? Can you send me money?” “You know the deal, Nancy. Go to the doctor and tell him to send the bill to me. I’ll pay him directly. What’s wrong with your kidneys?”

“Wait, Mum. Sid wants to talk.”

Sid got on. “Debbie?”

“Yes, Sid.”

“Why won’t you help your daughter?”

he demanded. He sounded different — harsh and unpleasant.

“I will, Sid. I’ll pay her bills directly to the doctor. That’s always been our — ”

“Her health comes first!”

“I know that, Sid. I will pay her medical bills. Directly to the doctor.”

“But it’s your daughter’s health!” he snapped angrily.

“Sid, I —”

“We need three thousand dollars! For the doctor! Send it at once!” he ordered.

“No.”

“We must have it!” he insisted.

“I said no, Sid! Please put Nancy back on.”

“What kind of mother are you? How can you do this to your own fuckin’ daughter?”

“Sid, in the first place, I haven’t got three thousand dollars. In the second place, a doctor’s appointment doesn’t cost that much! Now would you please put Nancy back on?”

“It’s your daughter’s health! Your daughter’s fuckin’ health!”

“Sid, would you please put — ”

“No! I won’t put Nancy on! Not until you — ”

“Put Nancy on or I’m hanging up!”

“How can you do this to your own fuckin’ — ”

I hung up on him, shaken. This was a side of Sid — hostile and belligerent — I hadn’t seen before. He frightened me.

The phone rang immediately. I wouldn’t answer it. Frank and I had made dinner plans with my mother. I told David not to answer the phone if it rang while we were out. It was ringing when we left. When we returned, David said it hadn’t stopped ringing the whole time we were gone.

It immediately started to ring again.

“See?” David said.

I decided to answer it. It was Nancy. “Mum, what happened before between you and Sid?”

“He was very nasty. I warned him I was going to hang up.”

“Wait, hang on.” She turned away from the phone to talk to Sid. “Here’s your match. Now light your cigarette and leave me the fuck alone,” she said to him. Then she was back. “He’s very upset, Mum. A very upset lad. He has a lot of problems.”

“Where is he now?”

“Right here. But he’s out of it. You don’t have to worry about him.”

Her voice was calm, her speech clear. It was the most lucid she’d sounded in a long time.

“Are your kidneys really bothering you, sweetheart?”

“Yes. I think I have an infection. I’ll be all right, though. I’ll go see a doctor tomorrow. What kind do you go to for kidneys?”

“A urologist. Go to the emergency ward of the hospital tomorrow and ask for one. If there isn’t one there who can treat you, call me. I’ll get you the name of someone in New York to see.”

“Okay, Mum, I will. Thank you.” She paused. “Mum?”

“Yes?”

“Did Daddy ever beat you?”

I was so taken aback by the question, I didn’t know how to answer it. I made a joke out of it. “No, but I’ve thrown a few things at him.”

There was silence from her end.

“Nancy, why do you ask?”

“You know all the times I told you I got beat up by the Teddys in London? Got my ear torn off? My nose broken?”

“Yes.”

“It was Sid who was really doing it. And… now he’s started doing it again.”

“Why?” I gasped, horrified.

“He’s upset.”

“Nancy, why do you put up with that?

Why don’t you leave him?”

“Because… well, he’s having a terrible time. He’s getting hassled. He can’t get work. He’s depressed.”

There was a long pause.

“Maybe one of these days you will find me on your doorstep,” she said softly.

“We’re always here for you, Nancy. If you ever hit the bottom and need us, we’re here to help you. You can count on it.”

“I am at the bottom, Mum. This is it.”

She’d come out of her fog. She was rational. We were communicating.

“Mum, do you remember that detox hospital, White Deer Run? It’s somewhere in Pennsylvania. Our next-door neighbor had to go there, remember?”

“Yes.”

“Do you think Sid and I could get in there? We have to get off. Just have to. Could you call? Could you find out for me if it’s locked? I don’t want to go if it’s locked. I can’t stand being locked up.”

“I know. I’ll call tomorrow and find out.”

“Thanks.”

“Let me know how you are. Let me know what the urologist says, okay?”

“I’ll let you know.”

“Good.”

“Mum?”

“Yes?”

“Does Daddy love me?”

“Of course he loves you. He’s always loved you very much.”

“He doesn’t act that way.”

“How does he act?”

“Like he’s afraid of me.”

“That’s because he has to walk on eggs with you, sweetheart. Everyone has to. You’re very sensitive. But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t love you. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Mum. I do. Tell Daddy I understand. And… and… ”

“And what?”

“Tell him that I love him.”

“Okay, sweetheart, I will.”

“How’s your mom? How’s Essie?” She hadn’t asked about her grandmother in three years.

“She’s fine.”

“Send her my love, will you?”

“I’ll do that.”

“Good-bye, Mum.”

“Good-bye, sweetheart.”

As I hung up the phone I heard her yell, “I love you, Mommy! I love you!”

I wanted to tell her that I loved her, too, but it was too late. The connection was broken.

I gave Frank her message.

“Nancy said that?” He was surprised and touched.

“Uh-huh. It was a very strange call, Frank. Spooky, kind of. It was almost as if she were saying good-bye.”

I called White Deer Run on Monday afternoon from the office. The woman I needed to speak with in admissions was out sick. I was told to phone later in the week.

Nancy didn’t call on Monday night. I supposed she had nothing to report about her kidneys.

Nancy didn’t call on Tuesday night, either. I had a vague uneasiness, but I didn’t give in to the temptation to call her. If she was coping with her problems, I didn’t want to interfere with the process. She knew where to reach me.

She didn’t call on Wednesday either. Wednesday was Yom Kippur. I became more uneasy.

On Thursday morning it was glorious and crisp, a beautiful autumn day. I drove to the office early, my mind on all of the work piled up on my desk. I made a mental note to phone White Deer Run, but crises kept coming up at the office and I still hadn’t had a chance to call at two o’clock.

I was coming out of the computer room and crossing the main office to my own office when one of the secretaries said, “Debbie, you have a call. The receptionist wants you to buzz her before you take it.”

I buzzed the receptionist.

“It’s a Lieutenant Hunter from the Lower Moreland police,” she told me. “I just thought you’d like to know.”

I wondered what the local police wanted of me.

I thanked her, and picked up the telephone on my desk.

“This is Deborah Spungen,” I said. “Can I help you, Lieutenant Hunter?”

He sounded very uncomfortable.

“Your… next-door neighbor told us where to find you,” Lieutenant Hunter said. “We were out at your house.”

“What’s this about?” I asked.

“The, uh, New York Police Department would like to speak to you. Something has happened to your daughter Nancy.”

“What happened to her?” I pressed, confused by his vagueness

He didn’t answer me. Instead he gave me the name of a detective and a number to call in New York. Then he was silent.

Suddenly my face felt very hot.

“Lieutenant, please tell me what happened. It’s okay. I’m ready for anything. Believe me. But I will not hang up this phone until you tell me what has happened to my daughter.”

“Mrs. Spungen, I’m sorry to tell you that your daughter is dead.”

My first reaction was disbelief. We’d been through so much together over the past twenty years. I had thought I’d somehow sense her death. I did not.

But it was over, really over. My head seemed to swell up in response, as if someone were using a bicycle pump on it. It must have been a drug overdose. What else could it have been?

Since I shared my office with somebody else, I went to look for my boss to ask him if I could call the NYPD from his office. He wasn’t in his office. I went out into the main office. There were a hundred or so people working and talking out there. They made no noise. Their world was soundless. I felt like I was floating, my head up somewhere near the ceiling.

I did find a vice-president, talking to someone at a desk. I stood beside him for a minute, but he didn’t seem to notice me. I thought about just waiting there until my head exploded all over the place. Then he’d notice me.

I didn’t wait. “Nancy’s dead!” I shouted. “Can I use Joe’s office?”

He stared at me, stunned. Everywhere people looked at me. He nodded.

I went into Joe’s office, shut the door, and dialled Detective Brown in New York. My dialling finger shook. I was reacting with a bit more emotion than I’d expected, but I was in control.

“I’m sorry to tell you your daughter has been murdered, Mrs. Spungen,” Detective Brown said in a kind voice.

Murdered.

My baby. Murdered. It couldn’t be. It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

According to Manhattan Chief of Detectives Martin Duffy, Sid had awakened at 10:50 AM, still feeling the effects of Tuinal, a depressant he had taken the night before.

Nancy was not in bed next to him. Rather, the bed was covered with blood. Her blood. A trail of it led from the bed to the bathroom. Nancy was on the bathroom floor, under the sink, clad only in her fancy black underwear, a stab wound in her stomach. She’d bled to death.

The Chelsea Hotel switchboard, the police spokesman advised, received an outside call at about this time asking that someone check room 100 because “someone is seriously injured.” It was not clear if the call had come from Sid.

Hotel employees went up to the room to find signs of a struggle, and Nancy’s body. Sid was not in the room. He returned a few minutes later, before the police got there.

Hotel neighbors reportedly heard Sid tell police, “You can’t arrest me. I’m a rock ‘n’ roll star.”

One of the arresting officers reportedly replied, “Oh, yeah? Well, I play lead handcuffs.”

An unidentified friend of the couple, the TV newsman reported, said he had been out with them that night until 4:00 AM, at which point Nancy had begged him to come back to the Chelsea with them because Sid was “acting strange.” Sid had, the friend said, pressed a hunting knife against Nancy’s throat. “He beats her with a guitar every so often,” the reporter quoted the friend as saying, “but I didn’t think he was going to kill her.”

After the funeral there was quite a lot of mail, much of it condolence notes. One letter was addressed to me personally in large, shaky handwriting with little circles over the i’s instead of dots. There was no return address. I feared it was an obscene letter. I took a deep breath and opened it.

It was from Sid.

“Dear Debbie,

Thank you for phoning me the other night. It was so comforting to hear your voice. You are the only person who really understands how much Nancy and I love each other. Every day without Nancy gets worse and worse. I just hope that when I die I go to the same place as her. Otherwise I will never find peace.

Frank said in the paper that Nancy was born in pain and lived in pain all her life. When I first met her, and for about six months after that, I spent practically the whole time in tears. Her pain was just too much to bear. Because, you see, I felt Nancy’s pain as though it were my own, worse even. But she said that I must be strong for her or otherwise she would have to leave me. So I became strong for her, and she began to stop having asthma attacks and seemed to be going through a lot less pain. [Nancy had had asthma since she was a child.]

I realized that she had never known love and was desperately searching for someone to love her. It was the only thing she really needed. I gave her the love that she needed so badly and it comforts me to know that I made her very happy during the time we were together, where she had only known unhappiness before.

Oh Debbie, I love her with such passion. Every day is agony without her. I know now that it is possible to die from a broken heart. Because when you love someone as much as we love each other, they become fundamental to your existence. So I will die soon, even if I don’t kill myself. I guess you could say that I’m pining for her. I would live without food or water longer than I’m going to survive without Nancy.

Thank you so much for understanding us, Debbie. It means so much to me, and I know it meant a lot to Nancy. She really loves you, and so do I. How did she know when she was going to die? I always prayed that she was wrong, but deep inside I knew she was right.

Nancy was a very special person, too beautiful for this world. I feel so privileged to have loved her, and been loved by her. Oh Debbie, it was such a beautiful love. I can’t go on without it. When we first met, we knew we were made for each other, and fell in love with each other immediately. We were totally inseparable and were never apart. We had certain telepathic abilities, too. I remember about nine months after we met, I left Nancy for a while. After a couple of weeks of being apart, I had a strange feeling that Nancy was dying. I went straight to the place she was staying and when I saw her, I knew it was true. I took her home with me and nursed her back to health, but I knew that if I hadn’t bothered she would have died.

Nancy was just a poor baby, desperate for love. It made me so happy to give her love, and believe me, no man ever loved a woman with such burning passion as I love Nancy. I never even looked at others. No one was as beautiful as my Nancy. Enclosed is a poem I wrote for her. It kind of sums up how much I love her.

I would love to see you before I die. You are the only one who understood.

Love, Sid XXX

PS. Thank you, Debbie, for understanding that I have to die. Everyone else just thinks that I’m being weak. All I can say is that they never loved anyone as passionately as I love Nancy. I always felt unworthy to be loved by someone so beautiful as her. Everything we did was beautiful. At the climax of our lovemaking, I just used to cry. It was so beautiful it was almost unbearable. It makes me mad when people say, ‘You must have really loved her.’ So they think that I don’t still love her? At least when I die, we will be together again. I feel like a lost child, so alone.

The nights are the worst. I used to hold Nancy close to me all night so that she wouldn’t have nightmares and I just can’t sleep without my beautiful baby in my arms. So warm and gentle and vulnerable. No one should expect me to live without her. She was a part of me. My heart.

Debbie, please come and see me. You are the only person who knows what I’m going through. If you don’t want to, could you please phone me again, and write.

I love you.”

I was staggered by Sid’s letter. The depth of his emotion, his sensitivity and intelligence, were far greater than I could have imagined. Here he was, her accused murderer, and he was reaching out to me, professing his love for me. His anguish was my anguish. He was feeling my loss, my pain — so much so that he was evidently contemplating suicide. He felt that I would be able to understand that. Why had he said that?

I fought my sympathetic reaction to his letter. I could not respond to it, could not be drawn into his life. He had told the police he had murdered my daughter. Maybe he had loved her. Maybe she had loved him. I couldn’t become involved with him. I was in too much pain. I couldn’t share his pain. I hadn’t enough strength.

I began to stuff the letter back in its envelope when I came upon a separate sheet of paper. I unfolded it. It was the poem he’d written about Nancy.

Nancy

You were my little baby girl.

And I shared all your fears.

Such joy to hold you in my arms

And kiss away your tears.But now you’re gone there’s only pain.

And nothing I can do.

And I don’t want to live this life

If I can’t live for you.To my beautiful baby girl.

Our love will never die.

I felt my throat tighten. My eyes burned, and I began to weep on the inside. I was so confused. Here, in a few verses, was the last twenty years of my life. I could have written that poem. The feelings, the pain, were mine. But I hadn’t written it. Sid Vicious had written it, the punk monster, the man who had told the police he was “a dog, a dirty dog.” The man I feared. The man I should have hated, but somehow couldn’t.

A few days after that I got a second letter from Sid, this one even more anguished than the first. Sid’s second letter also gave me insight into what might have happened that night at the Chelsea.

“Dear Debbie,

I’m dying. Slowly, and in great pain. My baby is gone, without her I have no will to live. I love her so desperately. I know I can never make it without her. Nancy became my whole life. She was the only thing that mattered to me.

I’m glad I could make her happy. I gave her everything she ever wanted, just for the asking. When we only had enough money for one of us to get straight, I always gave it to Nancy. It was less painful to be sick myself than it was to see her sick.

When you love someone that much you cannot lose them and still be able to go on. I know that if I lived to be a thousand years old I would never find anyone like Nancy. No one can take her place. I love Nancy and Nancy only. I will always love her. Even after I am dead.

I have only eaten a few mouthfuls of food since she died. I may die of starvation in this place. I just hope it comes soon, so that I can be with Nancy again.

We always knew that we would go to the same place when we died. We so much wanted to die together in each other’s arms. I cry every time I think about that. I promised my baby that I would kill myself if anything ever happened to her, and she promised me the same. This is my final commitment to the one I love.

I worshiped Nancy. It was far more than just love. To me she was a goddess. She used to make me kiss her feet before we made love. No one ever loved the way we did, and to spend even a day away from her, let alone a whole lifetime, is too painful to even think about. Oh Debbie, I never knew what pain was until this happened. Nancy was my whole life. I lived for her. Now I must die for her.

It gave me such pleasure to give her anything she wanted. She was just like a child. She used to call me ‘daddy’ when she was upset, and I used to rock her to sleep. When I was upset, I used to call her ‘momma’ and she used to nurse me at her breast and call me her ‘baby boy.’

I tried to kill myself but they got me to the hospital before I died. Nancy knows that I will soon be with her. Please pray that we will be together. I can never find peace until we are together again.

Oh Debbie, she was the most beautiful person I ever knew. I would have done anything for her.

Nancy once asked if I would pour petrol over myself and set it on fire if she told me to. I said I would, and I meant it. If you would happily die for someone, then how can you live without them? I can’t go on without her. She always said she would die before she was twenty-one, and I never doubted it.

Goodbye, Debbie. I love you.”

I didn’t write back to Sid. I never heard from him again. I kept his letters to me a secret from everyone except Frank. I felt that if I disclosed them to the police, somehow they’d end up in the newspapers, end up being sensationalized. I didn’t want that. They were private, personal letters. He made no threats in them. He bared his soul. The letters weren’t meant to be shared.

I disclose them now because they shed light on what happened that night and might help others to understand what Nancy and Sid really meant to each other outside the limelight. I disclose them now because Nancy and Sid are gone. They can no longer speak for themselves…

On February 3, 1979, Sid Vicious died from an overdose of heroin. He had been released on bail from Riker’s Island, where he had been imprisoned for three months.