One of our nation’s most prestigious journalists celebrates our rediscovery of the American Dream.

The New Patriotism

The sense of national pride that swept the country since the onset of Operation Desert Storm has about it a unique, almost unprecedented character. Not since World War ll have Americans been so taken with national symbols, so unabashed about indulging themselves in simple manifestations of patriotism.

Fierce pride and a sense of national renewal define America’s mood as we celebrate our 215th birthday with homecoming ceremonies for Gulf War veterans supplementing the usual fireworks displays and 4th of July parades. Flag decals adorn car windshields; actual flags fly from apartment windows and on suburban lawns; yellow ribbons remain plentiful; and lusty voices since the National Anthem with rare enthusiasm at sporting events.

Some of the superficial patriotic trappings will disappear, but we’re seeing a phenomenon that’s deeper than a momentary desire to feel good about America. In fact, many Americans are emerging from an extended period of uncertainty about this country and its prospects. Whether we call it the “Vietnam syndrome” or the “national malaise” (to use Jimmy Carter’s term), a tepid, tentative, unhappy period is drawing to a close.

That’s as it should be. Americans have a lot to be proud of, and we have lots of reasons for optimism.

The Gulf War taught us a fair bit. American soldiers fought courageously and well.

Why?

Because they were disciplined, confident of their training, and motivated. They were animated by a genuine sense of purpose — they believed in what they were doing.

The war also taught us that American technology actually works. All those who have argued that Americans can’t make anything good anymore would do well to remember that most of the weaponry and equipment used in the battle to liberate Kuwait was designed and manufactured right here in the United States. Obviously, when we put our minds to it, we can still assemble some pretty sophisticated stuff. And if we can make the tools of war — not to speak of the means to explore space — why should we concede an inability to compete with other countries in more mundane areas of technological endeavor?

We learned from the war that the nations of the world still look to us for leadership. For all the talk of America’s decline, despite the widespread attention to a united Europe and an ascendant Japan, when the chips were down, all eyes focused on Washington, D.C. Not just because, in a military sense, we’re the last remaining superpower, but because, even at our advanced age, we’re still on the ideological cutting edge. Democracy — American-style democracy — is the wave of the future.

The death of Communism as a competing ideology was no accident. It is democracy and capitalism — the free-enterprise system — that attract imitators. Democratic ideals continue to inspire protests and rebellions the world over.

And it’s because of this society’s fundamentally democratic character that immigrants from across the globe continue to flock to these shores. From Haiti to Ireland to Korea, young (and not-so-young) men and women still do all they can to get here. Their goal? To build new lives here; to raise their families here; to realize their hopes and dreams here.

The perception that America remains a land of opportunity endures for a reason — it’s true.

While it’s altogether natural that patriotism should flourish in this context, a fair number of people find overt manifestations of patriotism inherently unsettling. They see only its most negative potential attributes: mindless jingoism, intolerance, and militarism. Thus, those of us who are genuinely encouraged by the advent of a popular patriotic sensibility have a challenge ahead: We need to define an intelligent patriotism for the nineties.

This is a time for Americans to “count our blessings,” and it’s important that we identify the particular blessings on which to focus. If we ask ourselves what’s best about contemporary America — and what’s most salient in. the American national experience — the answer turns on the same fundamental fact that draws so many newcomers to these shores: The American Dream is alive and well. It is real and constant — it is not a myth, and it is not a happy piece of distant history.

This, in other words, remains a society with fewer barriers to opportunity and success than any other in civilization’s long history. America remains a land where virtually everything is possible, where upward mobility is an altogether legitimate expectation, where barriers based on class, race, creed, and national origin have been eliminated to a degree unprecedented in any great nation. And no sacrifice in terms of, say, ethnic identification or religious practice is expected as a quid pro quo for making it.

The rewards bestowed on those who work hard and manifest genuine talent are boundless. In recent years alone, a refugee from religious persecution in Nazi Germany, Henry A. Kissinger, rose to the office of secretary of state. An immigrant from China, A. N. Wang, created one of the nation’s leading computer empires. A black graduate of the City College of New York, General Colin Powell, currently heads the American armed forces. Indeed, the list of those who rose to the top from humble origins-smashing any and all perceived barriers — is virtually endless.

Consider, also, the winners of the most recent Westinghouse Science Competition for talented high school students. The list, which reads like a miniature United Nations roll call, is a roster of recent immigrants — from Russia, China, Korea, Vietnam, Eastern Europe, and Africa. By dint of diligence and aptitude, young people who’ve. been in this country no more than a couple of years — and who still speak English in the accents of their native lands — have been awarded keys to futures brighter than those their wildest dreams would have allowed them to imagine.

A society capable of absorbing new-comers in this fashion has to be blessed with rare strength and self-confidence. And this self-confidence has created internal resilience. That’s what makes it possible for free political debate to flourish here, and for full freedom of expression to thrive.

Was it a sign of weakness that far-reaching debate and rare soul-searching preceded the January congressional decision to authorize the use of force in the gulf? To the contrary, only a nation sure of its values could have permitted so open an expression of dissent on the eve of a major armed conflict. Only a nation confident that its citizenry and its leaders would rally to the cause — no matter what their initial views on the wisdom of going to war — could have allowed a debate of the kind that took place.

No one feared for the survival of the Republic as a consequence of public dissent. We live in a nation committed — again, on a level unprecedented in history — to protecting the civil liberties of even those who oppose democracy itself. Such is our confidence in our institutions and our national ideals.

“Only a nation confident that its citizenry and its leaders could rally to the cause-no matter what their initial views-could have allowed a debate of the kind that took place.”

Moreover, we live in a society prepared to confront and acknowledge past error. This is exceedingly rare, even in genuine democracies. Yet the popular culture here regularly includes widely acclaimed films and plays about the darkest moments in recent American history. The internment of the nisei (Japanese-Americans) during World War II was the topic of one recent film. That film was produced on the heels of a congressional decision to pay reparations to those who were interned, and to their descendants — in apology for the indefensible wartime order to send Japanese-Americans to camps in the western desert.

Many are the films and plays that treat the excesses of the McCarthy-era “Red Scare.” The Irwin Winkler film Guilty by Suspicion, with Robert De Niro, is but the most recent such enterprise.

A society capable of admitting error, of acknowledging behavior that fails to conform to the ideals that define America, has to be built on a firm foundation. Thus, the extraordinary tolerance that informs American political discourse. Thus, the willingness to allow critics of the war to mass on the steps of the Capitol in Washington and denounce American policy while our troops are in the field. And thus, the optimism that leads most Americans to believe — even in the face of economic setbacks — that no domestic problem is so big that we can’t somehow devise a way to deal with it.

We live in a society capable of bouncing back. America’s current encounter with greatness, after all, represents a return — after a period of nearly two decades — from the depths of despair.

Recall the bicentennial of 1976. For all the tall ships and proud flags, it was a hollow affair, a joyless celebration at a less than optimistic historical moment. The Vietnam experience had called into question nearly everything we thought we stood for — freedom, rectitude, armed might. No longer was it clear that America aroused the admiration and envy of the world. Instead, we seemed to constantly provoke disdain and even hatred.

And, of course, the Watergate affair raised doubts here at home about the integrity of our political system. Still, the 1976 celebration went forward. Eventually, our determination to put a black period behind us was crowned with success.

Now we stand at a kind of pinnacle. No nation is stronger. No nation enjoys such universal admiration. No nation draws nearly as many would-be immigrants. Patriotic fervor is altogether appropriate.

An intelligent patriotism would endeavor to safeguard the core elements of the American Dream over the next decade. First and foremost, we need to protect the twin principles of opportunity and mobility. Americans and potential Americans need to know that this remains a land where anything in the way of achievement is possible; where there are no major barriers to the advancement of those who work hard and demonstrate aptitude; where people are judged as individuals, not in accordance with race or creed or ethnicity or gender.

The threat here comes, in large measure, from those who would transform the principle of affirmative action into reverse discrimination — from those who believe in racial and other quotas. Apportioning rewards on the basis of race or ethnicity, even if prompted by an interest in redressing past discriminations, has the inevitable effect of denying opportunity on the same basis. Such practices run counter to the values that define the American Dream; they undermine Martin Luther King, Jr.’s vision of a society in which men and women are judged “not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Whether we see ourselves as a “melting pot” or as pieces of a “gorgeous mosaic,” America needs to remain a nation of individuals — a land where people succeed or fail in accordance with their own private gifts and flaws.

An intelligent patriotism would also safeguard dissent and free expression, particularly in the academy. Sadly, university campuses throughout the country have become citadels of intolerance. “Politically correct” thinking is the order of the day. From Duke to Stanford to the state universities of New York, Western culture and democratic values are mocked and heckled.

Students, teachers, and visiting speakers — save for the bravest — fear the implications of failing to conform to new political norms. “Codes of conduct” — barring racist, sexist, homophobic, and other ostensibly retrograde forms of speech — have been introduced on campuses.

The traditional curriculum itself is under assault. “Eurocentrism” — the teaching of the classics of Western culture, from Plato to Shakespeare to John Locke — is denounced by students and faculty as inherently racist. The chant “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Western culture’s got to go” was first aired at Stanford. Now, however, the tendency to crusade against the study of books and art works by “D.W.E.M.s” (dead white European males) is standard fare at major universities.

The push for an Afro-centric curriculum, in place of the traditional course of study, is also a national phenomenon. Its advocates readily admit that their purpose is less to teach than to raise the self-esteem of non-white students. In other words, the search for academic truth is being replaced by a quest to make students feel better about themselves. The result of this quasi-therapeutic approach to teaching is a form of ethnic cheerleading.

The entire phenomenon is characterized by marked intolerance. Opposing views are derided as racist. And insofar as academic institutions are crucial to keeping the American Dream a reality, the advent of intellectual intolerance and disrespect for free inquiry on our campuses is a blow to that dream. Here, then, is another item that belongs on the intelligent patriot’s agenda for the nineties: safeguarding freedom of expression on campuses and ensuring the survival of the traditional curriculum — at least for those who want to pursue it.

But let’s bear in mind how much is already in place, how many blessings we have to count. We live not just in the earth’s richest country, but in its most generous. While our sheer size and diversity create near-terrifying social problems — including the appearance of a massive urban underclass — no one disputes the obligation of society at large to feed, clothe, and shelter people who don’t or can’t work. No one disputes the view that everyone is entitled to health care as a matter of right. Not that there’s general agreement on how to address certain very real social crises such as the presence of the mentally ill and the homeless in the streets of large cities, the multigenerational welfare-dependency cycle, growing illiteracy, and high crime.

But few doubt that America will produce answers and policies and programs. Few doubt that America will preserve its internal resilience, its commitment to broad individual liberties, and its determination to keep open opportunity a fact of life. Thus, the immigrants will continue to arrive. The economy, in all likelihood, will adjust and expand.

If the renewed confidence in our national prospects requires anything to sustain it over the next decade, it’s good leadership. Political leaders guided by an understanding of the nation’s immediate needs — set in the larger context of the American Dream — sometimes seem few and far between. But such men and women do appear.

Those who feared that George Bush wouldn’t rise to the occasion when tested by fire have been proven profoundly wrong. This wasn’t the first time that the American people underestimated their leader. And it won’t be the last.

The system works, the dream is constant, the values firm, the future promising. We have a lot for which to be grateful. Good reason to be proud. And much to safeguard. That’s not a bad way to head into the twentieth century ’s final decade. For Americans, patriotism makes sense.

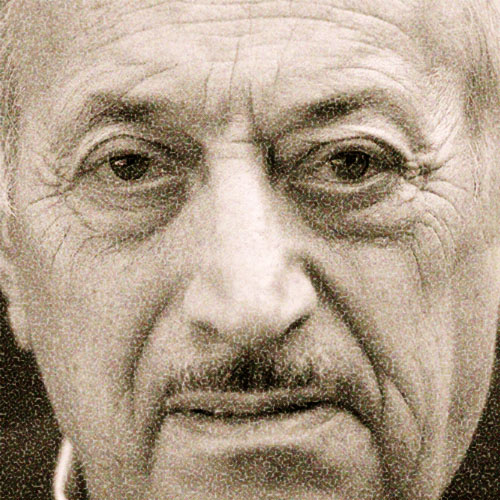

The esteemed author of this piece died at a very young age, sadly. Think about how much has changed since early 1998, and you’ll have some sense of what we all could have learned from this very special mind.