Considering the current political climate and the ping pong game that seems to define our current political system, we thought it might be interesting to look back at the era of President Nixon. Notice, please, that we chose “interesting” rather than “helpful” with that diction.

Americans Hate Politicians

This is a report of a three months’ journey around the United States, during which time I talked to ordinary people in ordinary situations about an extraordinary subject: the utter and absolute corruption of politicians and of the political system. The trip covered the end of the Nixon era, the Ford honeymoon, and people’s rude awakening when he pardoned his old boss. I traveled from coast to coast, north and south.

I didn’t formally interview people. We talked, stranger to stranger, chance acquaintance to chance acquaintance. I didn’t take a poll and I didn’t work out a scientific sample. I didn’t inhibit the conversations by taking notes or running a recorder or doing anything beyond what you do every day yourself when you talk to people you meet. I spoke to people on the job or near it, at lunch, waiting in lines, at stores, in cafes, on corners, in cabs, on trains, in buses.

I spoke to about seven hundred people. My notes were taken, always, after the conversations and they concentrated on highlight quotes and moods.

The subject was always the same: politicians and politics. If they didn’t bring it up, I did. And I’ve concluded that almost all Americans now are absolutely convinced that politicians are crooks; that politics is dirty, and, even more significantly, that it is a dirty business — it is both dirty and a business; and that big money is just as bad.

This doesn’t mean that Americans are about to do anything about it. The talk was cynical, not revolutionary — so cynical that it’s possible people could finally accept the biggest crook, with the biggest promises and the biggest lies. Or — hopefully — people could move beyond cynicism into a healthy skepticism that would actively reject politicians and politics as now established and organize a new force for social change and even a new democracy.

There were exceptions to all of this. There is a social line, it seemed to me, that sharply divides the vast majority of people who are fed up with politicians, and those who continue to have both faith and a well-defined stake in politics and business as usual. The latter includes the people who travel regularly on jets, have substantial expense accounts, make their living by wheeling and dealing more than by creating or producing, most lawyers, managers, people with an eye on elective office themselves, people living off inheritances or from the ownership of property, and the people who, from butlers and valets to vice presidents, might be called the servants of the very rich, who are all still very enthusiastic about politics. It is, after all, seen as their politics, dominated by their people, and representing, by and large, their interests. However, it is unlikely that this group numbers more than five million people.

There are tens of millions of other Americans who are more like most of the people I spoke with. I can’t say, of course, whether they all talk like the people I met. But, when talking naturally and on their own, I am convinced that these tens of millions also would say that politics is a dirty business, that politicians are crooks, and that something deeply corrupt is eating at the vitals of the land which they actually and dearly love despite it all.

This is the way it sounded, all across America:

At a Los Angeles magazine stand, talking to the vendor. “Will you look at that? I swear, everything you got there is putting down some politician or another.”

“Ain’t nothing. That’s just the ones they catch. If they told the truth about all of them, I wouldn’t have space enough.”

“Hey. There’s one about that guy who shot Wallace. What you think of that one?”

“I’ll tell you what I think, mister: I think Nixon paid him off. You know, who else got anything out of it? I think Wallace could have beat that sonofabitch and I think he had him shot. You wait and see.”

“That’d really be something, wouldn’t it? How about Wallace? You like him?”

“Aw, shit, mister, I guess he ain’t no worse. But I tell you, I wouldn’t wanta catch him around the cash register. You can bet they’re all crooks when they smell that money.”

At a downtown L.A. car wash, during a lunch break. A policeman, apparently off-duty, has been talking to three washers. There is seemingly good-natured laughter. The policeman walks away. I swap half a salami sandwich for an egg salad, borrow a bottle opener for some pop, and we talk. It gets around to the usual.

“We get some of them hot shots from downtown in here with the big cars. You think they tip? Shit. You lucky, man, to get the time of day. Acting so big. What do they do? You ever hear one of ’em do anything? Just fuck it up more. That’s what they do. Steal, man. We gonna all die here in the smog, but they don’t give a shit. They gettin’ what they want and screw you, man.”

“Yeah. Maybe it’d be better if we could just do stuff for ourselves. Whattaya think? Couldn’t do any worse, could we? Like you guys could run this thing, couldn’t you? Maybe you could run things where you live too, with the other people there. Just run things without the politicians.”

“Yeah. Couldn’t be worse. But I don’t know. Maybe it’s all gone too far.”

“What about that cop you were talking to? You got along okay with him.”

“You gotta be kidding, man.”

“How’s that?”

“He takes, man, he takes. They all take.” Lunch is over. They clean up some litter. No one told them to. But it’s obvious this tiny turf at the corner of the building is theirs: they respect it. Back on the wash line they are like mechanical people. And they obviously don’t give a damn. Cars go through with mud streaks untouched. Brushes are dropped and kicked aside. And at the cashier’s cage a very bored, gray-haired lady is arguing with a customer who thinks she took him for some change.

On a plane headed for San Jose. There are two California law enforcement officers behind me. Their view of the world is very different from anything else I encountered.

First they talk about office politics. They talk matter-of-factly about payola for city police chiefs, from other policemen, to get better job assignments. They use the phrase “peace officer” over and over rather than “policeman.” They have a strong sense of duty in a very special sense. Both speak proudly of the times they have gone out of channels to remedy an injustice, but in every instance it is a matter concerning promotion and pay. Only once do they even touch on the nature of their work. It’s a discussion — in the same tone of voice they use when discussing pay and promotion — about the use of hollow-point bullets to kill people. They like them. But they also have a gripe: shoulder holsters — they call them training bras — are hot and chafe. One of them says his wife could have come with him on the trip “but I don’t know what she would have done with the kids.” They are very clean talkers. Not even a damn in their talk, for the entire trip. As we deplane, and I can finally see them, they are the spitting image of everyone else on the plane. They’re all businessmen. Only one difference: their holsters chafe them.

“During those three months, I did not speak to one single, ordinary, on-the-streets sorts of person who had a kind word to say for politicians.”

In a San Jose diner, a very fancy place, with an old friend working in a local bank. The restaurant is filled with gleaming people and crystal. My friend is very sympathetic to the view that the politicians are really corrupt. Yes, he knows all that. But no, there’s nothing we can do except get some better politicians.

How about trying to do things ourselves, where we live, with our neighbors? No, won’t work. People just won’t take responsibility. Things are too complicated. Got to have experts. But who are the experts? Aren’t most of them just neighbors anyway? The experts aren’t the big politicians, they’re competent people who can build things, operate things, invent things. Right?

“Sure, sure. Right. But somebody has got to organize them. How would you get it all together without the political system?”

“But you just admitted that system was responsible for everything falling apart. How can you see it as the cure for the problems that it causes in the first place?”

“Get better people.”

“Why hasn’t that happened so far? How come it gets worse rather than better? What makes you think we’ve just had a run of bad luck with leaders? Can’t you imagine that the whole idea of a few people running everything is a system — one that produces bad results?”

“I hope not.”

“What do you mean?”

“I hope not, because I’m part of the system. I couldn’t live outside of it. You can’t seem to understand that. You can’t go around expecting people to give up what they’ve got. I won’t. Who would? That’s all there is to that. You may say it’s bad. Sure. It could be worse, though. As it is, I’m still getting a fair share of it. I intend to keep it. It’s as simple as that.”

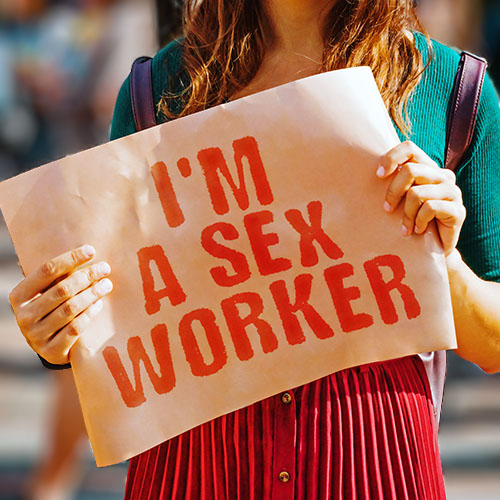

With some young people on a Farm Workers picket line in Arizona. Ten years ago they would have been working for some reform candid ate, and they still haven’t abandoned politics altogether — they use it as they can. But they are no longer political groupies or hero-worshipers.

“We had to learn. And we did. Camelot, all that shit. Had to go through it. Now we know they all use us, all of ’em. Waste us. We know that politicians aren’t an answer anymore. They’re just like steps on the way. We really know that. They’re crooks, too. If it wasn’t Nixon stealing, it would be a Democrat stealing. We know that. Really know that. So we’re back where we belong, I think. Back in the unions. Back in the neighborhoods. Working. We know where it’s at now. We know where we’re at.”

With a really nice lady at a motel. She and her husband started the business after getting fed up with the dirt, the toil, and the turmoil in the east. Now there’s an almost steady dust storm blowing from the construction work that surrounds the motel in a sea of progress.

“It can’t just go on like it is forever. I think this thing with Nixon is, well, just about the end of the road. I just know it can’t go on like it is.” She waves at the seemingly unending ripping of the land, the building for building’s sake, the dust hanging like a curtain between where we are and somewhere else where the air is clear. “It can’t go on like this.” She says it several times. Then she punctuates it. It’s like a very shy little period at the end of an anguished sentence.

“But….”

Texas. If there’s any place where there should be boundless, undiminished, shining, glowing, shouting, howling, defiant faith in the Big Game, in politics, in politicians, it should be here, right?

Two hours in the Dallas-Fort Worth airport. It’s big enough to be a town to itself. It’s also far enough away from anyplace else. The phones don’t even take dimes — they start with a quarter. And here are the people who say they believe in the system. The people who figure they are the system. The people who take politics and politicians seriously, who have opinions and favorites … who know what’s what.

You don’t catch these people falling for any hysterical nonsense about crooks in the White House. They know bigger crooks somewhere else. They knew that Nixon was their boy and they’re sort of sad that he got caught. But they certainly aren’t disillusioned. They are the great unmarked, unscarred, unbowed old faithfuls. The Boss, national or corporate, is God, and they are His apostles.

If polls were taken at airports, politics would look like the hottest ticket in town, now and forever. And since the airlines boast that they haul almost 200,000,000 passengers a year, there is a sudden temptation to think that means all America still loves its politicians, and that I’ve been just talking to a bunch of surly nuts out on the streets.

But the airlines’ statistics are deceptive. You get counted every time you step on board. In three months alone, I must have added a hundred passengers to the statistics, all by myself. And so do most of the people you see at the airport. They are always on the move. Maybe that’s one of the reasons for their vast faith in the Boss. They don’t have to spend much time sitting still for him or with him. So the airport regulars, the real rooting section for the politicians, probably don’t number more than a million altogether. Even if you double or triple this number to include their families and the political faithful, you still have a small minority in a land which otherwise, I am convinced, is deeply, fully, and perhaps finally fed up with crooks in office and maybe even with crooks in offices.

Downtown Dallas. The foreman of a street crew, fixing up the aftermath of another one of those interminable tear-one-down, put-up-another building cycles.

“I’ll tell you this: I don’t care; long as we get the job done. Them monkeys can wear ribbons in their hair for all I care. Company used to be tight-assed about everything. Spit and polish. You better believe it. They don’t give a shit now. I don’t give a shit. Nobody gives a shit. You think I know what the fuck we’re doing here? I don’t care. They pay me. I pay them guys. We get the stuff done I don’t bother nobody. I don’t want nobody should bother me.”

“Wish those guys in Washington would listen to you.”

“Them pricks. You think they listen to anybody? I voted for Nixon, you know? I’d probably do it again. I wouldn’t trust that sonofabitch with my old lady’s aunt, and she’s half dead. But you know that other sonofabitch wouldn’t been one bit better, don’t you?”

“How about your boy, John Connally?”

He spits in the ditch. “He’ll end up where he belongs too. And I don’t think he even stole as much as them other guys.”

In a cab from the Houston airport. The driver is black. His bumper sticker says I fight poverty. I work. “They can have all them kids and hang around in beer halls. I gotta pay a $156 welfare tax so they can have al I them kids. Those old fogies in Washington won’t do anything about it. They don’t do anything about anything. They give them bums millions of dollars every year and you know they wouldn’t even give that Castro down in Cuba $47 million when he asked for it. That’s why he went over to the Russians, you know.”

There was one other part of the conversation that deserves separate note. The location of most American airports is, so far as most observers are concerned, purely political. The subject comes up, if you give it a chance, driving in from any airport. From twenty-five airports I noted twenty-five absolutely consistent comments. The location of the airport is ascribed to politics and greed.

Wherever, as a matter of fact, a question of large-scale public land speculation is involved — from airports to highways to schools to low-cost housing — there is a flat and foregone conclusion that the politicians make their choices on the basis, first of all, of making a windfall killing either for themselves or for their cronies. I did not talk to a single person who felt that the public welfare ran anything better than a poor second or third, if it even was involved at all. In no area is there a more deeply rooted disillusionment with the American myth of public service. Public land deals are seen as political spoils, nothing else.

“Wallace ain’t no worse than most politicians. But I wouldn’t want to catch him near the cash register.”

As a way of understanding how deep the general disillusion has now gone, imagine the sort of talk you might hear about a land deal, the sort of skeptical, hard-nosed acceptance of the political spoils system, and apply it to the loftiest governmental enterprise — diplomacy, statecraft, fiscal policy, what have you. It was my experience, from my entire interview-trip, that there is no action of government that now escapes this bone-weary, totally fed-up feeling.

Moreover, the passions once associated with politics have shifted to other parts of the civil anatomy. Things are now of paramount concern: jobs, money, appliances, automobiles, hospital bills, utility bills, shortages. Politicians are seen as being incapable of doing anything but making any of the Things get worse. There is not much talk about what can make Things get better.

A comment made by a journalist friend in Dal las sums up the potential violence of this attitude-the harsh shift to Thing consciousness from traditional political consciousness, the shift to Thing loyalty from traditional party loyalty.

“Can you imagine,” my Dallas friend said, “what an east Texas housewife would do to keep her air conditioner?”

It gets very hot in east Texas. Being cool isn’t merely a luxury or a comfort, it’s necessary for survival. My friend told me that Texans had switched their loyalties and even a lot of their concern from traditional party politics to worries about air conditioning and the gasoline which used to be part of their folklore but is now a threatened part of their lives. Ordinary people are unable to do a thing about these problems.

By the time I had left Texas, I was convinced that I had a good idea of the way in which Americans had come to regard politics as dirty, as a dirty business. But as I headed for Chicago, to appear on the nationally syndicated television show of Irv Kupcinet, I was still dealing with a down-on-politics attitude that seemed to have the Nixon White House as its focus.

The television show itself was a round-table chat with Senator “Scoop” Jackson — “the senator from Boeing” as he laughingly said people often identified him — and Tom Railsback, congressman from Illinois and a member of the impeachment panel. Jackson was running for president and Rails — back was agonizing about the heavy responsibility of deposing a monarch, a course he had already clearly realized would have to be taken.

After the show, talking with technicians and other off-camera people, I tried to get a sense of how pertinent our discussion had been to people in everyday life. Were the fates of the mighty the preoccupation of mere mortals?

“Oh, sweet Jesus, if I hear impeachment one more time — I think I’ll toss my cookies. Who the hell really cares? Everybody knows what Nixon is. So they’re gonna tie a can on him. So? Then we’ll get the next guy, Ford, and I suppose we’ll go through it all over again. Reruns. It’s like, so help me, reruns forever.”

“How about those guys on the show? That congressman seemed okay, huh?”

“Sure. Nice guy. You see him sweat about doing the number on Nixon? They really hate it, man, they really hate to stick it to one of their own. They’re all the same. All they really care about is their ass, man. Public servants, whoooeee.”

“Jackson, too?”

“Oh, man, he’s been here a lot, you know? Always the same. He comes in with those guys carrying his briefcase and whispering this and that and there’s always a car waiting, you know, and they just have to get the senator here and the senator there. You’d think he was some kind of rock star, man. Just putting it on, you know, running, always running.”

The conversation was part of another pattern. During my trip on behalf of Penthouse, I appeared on about two dozen television talk shows. The subject was roughly the same as my interviews, the state of politics in America and the possibilities of people living together without the sort of rigid, top-down authority that American politics and corporate gigantism has come to mean.

There was no exception to the reactions of people in the studios. The interviewers, expressing what they regarded to be the feelings of people generally, argued politely against the notion that people are fed up with politics and politicians. They trotted out everything they could think of as proof that the system is working, even if creaking. “Look,” the refrain would go, “Nixon has been caught, and Congress is beginning to reassert itself. People really are beginning to take an interest now. We’ve got to have someone running things, don’t we?”

Off-camera, the arguments stopped and an almost nostalgic note would be struck. “As a matter of fact, it does look pretty bad, doesn’t it? There doesn’t seem to be anybody we can trust anymore. As a matter of fact I can’t honestly say I know what’s happening anymore.

The mood of the technicians and the other people who work behind the scenes was tougher.

“You’re right. We’ve got to find a better way. Those people are all the same. So are the companies …. We might be better off if we could run it ourselves …. Something’s got to change. But what can we do?”

The on-camera people often felt helpless simply because of lack of knowledge. They were people who, by and large, frankly and earnestly admitted they had no skills beyond those of personality, of being pleasant on-camera, of “knowing the business.” Unlike many people in such a situation, however, they seemed vitally aware of the lack of real-world skills and seriously interested — someday, somehow, somewhere — in acquiring them. The people whom I have come to refer to as the airport people, the high-pressure execs and so forth, also lack skills beyond those of personality — mainly the personality skills of manipulation and of “knowing the business” of management jargon, in-fighting, and procedure. But, unlike the television people, they are not aware that this is a lack of knowledge. Unlike the television people, they do not even bother to theorize about the possibility that managerial skills might one day be secondary in comparison to real skills such as those of science, technology, crafts.

Thus, even though the television people are up to their hips in an industry dominated by top-down power and noncreative managerial types, they are much sharper than the airport people in questioning the stability of their situation, and they seem to reflect far more concern in their private conversations for their own role in a landscape of changed values and of declining faith in giant institutions.

It is quite possible that it is this purely native good sense, this skeptical and questioning edge to their natures, that makes so many television people move toward or at least flirt with anti-establishment positions — rather than the Agnew-type explanation of “bad politics.” My own observation is that, as a matter of fact, the television people have virtually no politics.

Atlanta, near a GM assembly plant, across from a penitentiary. The assembly plant could also be a prison: it has guards and rules and regulations which are prison-strict. I talked to a lower-level employee from the plant’s labor-relations department. He had to moonlight working in a garage now and then, just like the workers whose demands he is paid to resist during his ordinary working day. “What the hell,” he said, “it’s a living.” The labor-relations work was better than working on the line. The job in a garage was better than selling shoes. He is a good example of the way in which the galloping disillusionment with big politics is also manifested as a disillusionment with corporate bigness. Very learnedly, for instance, he went through the entire list of inventions he claimed were kept off the market to make profits for the major companies. His favorite was the thirty-five-mile-per-gallon carburetor which, he claimed, had been developed by GM several years ago and was bought up for four million dollars by the oil companies. The point is not the unprovable truth of the story. The point is that a white-collar employee of General Motors would be so convinced of its truth and so thoroughly cynical about the great corporation employing him. Corporate executives sometimes are said to comfort themselves with the feeling that they have loyal employees. They probably shouldn’t.

“If it wasn’t Nixon stealing, it would have been a Democrat. We know that.”

In downtown Atlanta, talking to a soldier on leave. “Why is there construction everywhere you look and at the same time so many people out of work? That doesn’t make any sense.”

Being a soldier? “Better’n nothing.” Worry about what the politicians may do to bring on another little caper like Indo-china? “Yeah. Sometimes. I don’t know what I would have done if I’d been in when that was going on. But also I don’t know what the guys who are in now would do. You know, they worry more about what they’ll do when they get out than what’ll happen while they’re in. They really worry, too. It doesn’t make sense. Al I that stuff and no jobs.”

Southfield, Michigan, outside of Detroit. A former General Motors employee. It’s hardly a coincidence to run into two GM types so soon. Only the federal government has more employees. This man also works in a garage; but he owns his own, having decided that the cars he used to build were sure to make the garage business a good one.

“No. I really don’t think much about politicians at all. They all lie, and they can’t do anything about anything. I don’t think it’s the politicians we’ve got to watch at all. It’s the big companies. They control the parts, you see. I mean, they control the bits and the pieces that everyone needs to put anything together. Anybody could make a car, for instance. But the big companies control all the bits and pieces. That means people get more helpless all the time. I can’t even fix everything. So many special tools — and all those parts, all those little bits and pieces.”

“But isn’t that like big politics? Don’t the politicians control all the little parts, too? Licenses, rules, regulations, all the taxes, all the police, all the bits and pieces?”

“Well, maybe you’ve got something there. But I still don’t worry so much about them as about the big companies. You got to give the companies one thing: they’ve got some smart people. But the politicians! My God! They’re really hopeless, you know. If they couldn’t get the dumb bunnies to vote for them, they’d starve to death. They’re really dumb. Not like the companies.”

In Cleveland, there’s a yard with an endless line of junk storage and steel scrap, including the scrap from automobiles like the ones GM builds. In one door, out the other. A guard talks about it just that way.

“I get a kick when I read the papers and all those big shots are telling you what’s wrong with the economy and everything. Whatta they know? This is what’s wrong with it: Junk. Everything is junk. Make it one day and scrap it the next. Hell, this junk is worth more than you or me, mister. People ain’t worth a penny compared to this stuff. And all you ever get from the politicians is just the same. It’s junk, too. You know, those guys spend so much time getting there, getting up to those big paychecks and those big titles on the door, they don’t have time for anything else. That’s all they do. They just get up there and hang on, brother.”

A waitress, on the Cleveland rapid transit, reading a book about a school that emphasizes freedom and responsibility. She’s very concerned about public schools.

“But they don’t really teach anything. They just make little people for the political system and the factories. I get scared when I think of my kids going to schools. All I ever learned there was how to get along with the system. Now that it’s going to pieces, we need to know more. I just don’t think we can leave it up to the schools anymore. Somehow we’re going to have to do it ourselves.”

Pittsburgh, near the former Duquesne brewery, talking to a man who had worked there for years until it was closed, he says, as the aftermath of a union struggle.

“You know, I’ve always thought the union should have taken the damn place over and run it themselves. We could have done it, you know.”

“How about politics, taking that over?”

“Oh, God, I don’t know. That’s so screwed up. But we couldn’t do worse, could we? I know things aren’t gonna get any better. You just watch. Those birds are no good at all. I tell you, we could have run the brewery okay. But I don’t know if anybody can run the country.”

And then Nixon quit.

Madison, Wisconsin, talking to a farmer in town for a weekend.

“Do you think they’ll let him get away that easy? I hope not. All those friends of his are in jail. He belongs there.”

“If he goes in, do you think that’ll set this political thing straight for a while?”

“Oh, I don’t know about that. Remember, that fellow, Ford, is the one Nixon picked. How different can he be? You know, I don’t think any of them is very much different. I know that they all make a lot of promises, but nothing happens. I don’t think any of them really mean all the things they say. I know this: I’d rather have some rain than all that politics. But I wouldn’t be surprised to hear one of them tell us he could make it rain. For votes, you know. I sure would take the rain, though.”

All of the above quotes. are highlights, chosen not because they’re special but because they’re typical. I did not speak to one single, ordinary, on-the-streets sort of person who had a kind word to say for national politicians. Even those politicians who, from time to time, people told me they either had supported or would support were mentioned very skeptically, usually as the least of many evils.

It was surprising that George Wallace arose spontaneously in only a small handful of cases. Where Wal lace was mentioned spontaneously, it was in terms of a sort of anger, as though by saying things like “Maybe Wallace is as good as any of them,” or “Wallace is right, there isn’t a dime’s worth of different between them,” they could affront the entire political system. Not one person said anything about Wallace being honest or an outstanding exception to the rule of general political corruption. Wallace may well be the candidate of people who can’t stand the regular parties or feel betrayed by them, and a Wallace vote would be a vote against the other politicians more than a vote for Wallace. Also, those who did mention him were not at all put out when I suggested that even with Wallace we had to wait and see; that maybe his record in Alabama wouldn’t turn out to be an inspiring as they hoped.

A stonemason in Atlanta. “Don’t you know it! Look, I used to think he could do no wrong. But I also thought that about Nixon. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if somebody told me Wallace was doing something wrong, too. Boy, I tell you, we sure have some hard lessons to learn!”

Were there racial differences in the comments? Yes. Black people with whom I spoke were more bitter, generally, about politics. They often spoke of politics as being always corrupt — not just now.

Age differences? None. Sex differences? Women and men were equally put off by politicians and politics. The women, if different at all, seemed a bit more saddened than angered.

The polls will probably continue to show some sort of in-between, gray feeling about such things. Politicians will continue to say that the system is alive and well, even if badly bruised. The young will continue to be exhorted to get busy and get into the political mainstream so that they can help clean it all up. Reformers will unfurl their banners. Crusaders will shine their shields. A few crooks will go to jail. A bright new face will appear here and there. There will be those moments when, as though your youth is reborn, you hear the fine phrases of the next white knight or black knight or lady knight saying that — if we just slay some dragon or another — the castle will be in as good shape as ever. There will be elections. There will be presidents.

“I wouldn’t trust Nixon with my old lady’s aunt, and she’s half dead. But the other guy wouldn’t have been one bit better.”

But there will not be, I am now convinced, any total return of confidence in the system as it was. Authority could replace democracy, of course. That’s always a possibility in a troubled time. Depression could smash the social structure.

The old ways are dead but the new way has not yet clearly been seen. The Rockefellers, the Kissingers, the banks, the CIA, the defense complex, the subsidized think-tanks, and the universities all are planning the shape of that future. Its outlines, in every case, are clear. If these people have their way, the future will be one of well-regulated order, with the good folks running the show, and with the “little people” exercising fully their right to ratify what the rulers propose. We’ll have social treatment for malcontents, professional care in every field from police to politics.

The orderly people have always had such dreams: everything in its place and a place for everyone; labor and management cooperating; a bipartisan foreign policy; economic technicians wisely at the helm; everything totally under control — most of all, you and me.

But for three months I talked to people who are not orderly and whose dreams are far different. They have always made a mockery of the charts and the blueprints of the experts. People just aren’t ink to make graphs look good. People get headaches and show up late. People go crazy on those neat assembly lines. People just can’t understand every demand for a triplicate form. People go AWOL. People get pissed.

I haven’t yet the vaguest idea of what the great changing majority of Americans will finally want to do with their lives and their history. They could choose to give up both to the powers that be or that will be. Why not? Millions of other people have …. Or tomorrow’s Americans could choose to make their own history.

Only one thing seemed absolutely clear from my trip and from the many talks: if there are to be leaders for the next great change in the way we live, they will not be the leaders who are familiar to us now. These people have used up most of their credit and all of their lies. The politicians we know in America today are a sad, soggy foundation for any different future.

If we are not to have leaders in the traditional sense, and instead, there is to be some new form of American democracy, more like the participatory, locally based society of our nation’s founding and frontier, then important elements of it will appear well outside the regular two-party system, because that system is no longer seen as a system for change or innovation.

But then again, the future could be something altogether different — something that the people who are just now despairing of the old ways still have to build… and tell us about!

Remember this article appeared in the magazine 50 years ago now, as of this update. Suffice it to say that not much has happened to increase our faith in government and politicians in general. Some of us subscribe to the philosophy that anyone who seeks public election thereby becomes unqualified for the position, because they want it. … OK. So some of us might be just a tad cynical.