“The movie business is now a cheap carnival sideshow, and the only people who are concerned with the content of films are the people who actually make them. The people who sell films don’t think like that.”

Altman: The Penthouse Interview

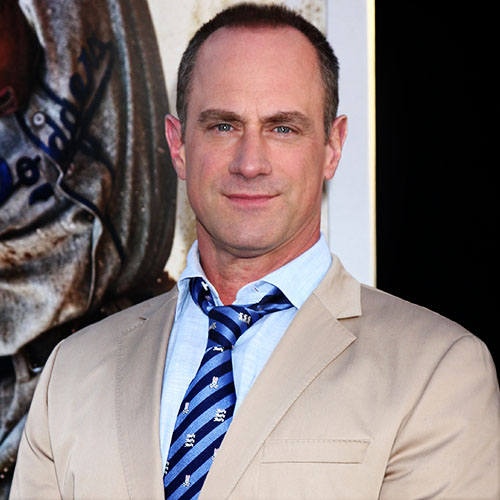

By now, Robert Altman has long since established himself as America’s most innovative and provocative filmmaker. The director of M*A*S*H, Nashville, and nearly a dozen other movies, Altman has a highly personal film following — and a highly personal film signature. Altman films are largely improvised, often indifferent about plot structure, and usually feature sound tracks with two or three characters talking at once. They don’t make movies like that anymore and never did, which is probably why Bob Altman’s work invariably sparks passionate critical debate.

A burly 55-year old, Altman has a well-earned reputation for being an outspoken maverick who takes no guff from anyone; yet he’s extraordinarily kind to the actors he employs. Carol Burnett, who’s appeared in two Altman films, says, “I think my best film work has been for Bob Altman, and it’s not surprising: he gives you so much confidence you’re not afraid to stick your neck out. I loved working with him, but that isn’t unusual — Did you ever hear of an actor who didn’t?”

Still, except for M*A*S*H and Nashville, most Altman movies have turned out to be exercises in red ink. Although cinema connoisseurs may have loved them, such Altman works as McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, Three Women, Images, and Thieves Like Us failed to generate any enthusiasm at box offices, while still others, such as Buffalo Bill and the Indians, Brewster McCloud, Quintet, and A Perfect Couple, didn’t win favor even among his fans. Altman, however, seems to care very little about how his movies fare. Says America’s most prolific director, “I’m happiest when I’m working, which is why I like to make movies: it’s fun.”

Born and raised in Kansas City, Mo., Altman was smitten by films the first time he saw King Kong, but in those days the sons of midwestern jewelers did not grow up and hop planes to the West Coast. Instead, Altman studied mathematical engineering at junior college, after which he served as a B-24 bomber pilot during World War II. Following his discharge, Altman spent two years — in Hollywood and in New York — trying to be a screenwriter and then went back home to Kansas City, where he spent the next eight years working for an industrial film company.

In 1957 Altman coproduced a documentary, The James Dean Story, and when Alfred Hitchcock saw it, he immediately signed Altman on as a director for his television series. During the next six years Altman directed hundreds of episodes of such shows as Combat, Bonanza, and The Whirlybirds. He finally got his first shot at a feature film in 1963. The movie was called Countdown — it starred a new-comer named James Caan — and Altman was fired because he allowed actors to speak simultaneously, believing it would add realism to the film. He wasn’t hired as a director again until 1968, when he made That Cold Day in the Park, a murky suspense drama that starred Sandy Dennis. Altman’s next movie was M*A*S*H, and almost overnight he became the talk of the film world.

To interview Altman, Penthouse sent free-lancer Lawrence Linderman to meet with the director in Los Angeles. “When I met him, 11 Linderman notes, “Altman was on the verge of his biggest film success — and biggest film failure. Health, a satirical comedy starring Lauren Bacall, hadn’t been released by Twentieth Century-Fox since being completed almost a year earlier, and it seemed certain the studio was about to give it a permanent deep six. At the same time, Popeye, starring Robin Williams in the title role, was being readied for a Christmas release, and all reports on the film indicated it would almost surely become the biggest box office winner of Altman’s career. When I met Robert Altman at the informal offices of Lion’s Gate Films, the company he owns, he was busily putting the final touches on the forthcoming Popeye. Rather than waste any time in the way of preliminaries, we immediately got right down to cases and began our conversation.

Most American film critics compare you with Fellini and Bergman, and each time you come out with a new movie they knock themselves out describing how brilliant — or terrible — they think your work is. How do you react to all that scrutiny?

I react emotionally, but let me first say that I really don’t think any of my films are brilliant or important. I don’t think they mean much more than an experience to the people who made them. I also find that the awkwardness at certain points in my films — things that didn’t work exactly the way I wanted them to — cannot be subtracted without destroying the rest of the film. To me, those moments become part of the positiveness of the film, and I wouldn’t go back and change anything. I mean, you could see one of my movies and tell me, “Look, Bob, I think you probably could have milked more out of this particular situation,” but those are like flaws — or imagined flaws — in a person. If you have a child who seems tall for his age, you might say to yourself, “I hope he doesn’t grow up to be six foot eight.” But if he becomes six foot eight, you say, “That’s my boy!”

Is that the way you feel about your movies?

I feel that way about all of them. It’s the same way you fall in love: you might recognize that a person has a lot of flaws, but many times those become the most endearing parts of someone you love. In terms of my films, I don’t think I’m striving for a kind of perfection where everyone will sit back and say, “Oh, that’s wonderful.” That’s impossible to do, anyway.

A movie is like a painting, and once it’s finished, to try and improve it is a mistake, like getting your nose fixed.

You said you react emotionally to critics. In what way?

My first reaction is surprise, I guess, because whether they like or dislike my films, critics always deal with them emotionally, not intellectually. I can almost predict what attitudes certain critics will have about my films. For instance, Rex Reed — who’s really not a critic but a gossip — didn’t like McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which was no surprise at all. But in his review he said something like, “And then this fake snowstorm came along, and it was just too much to take.” Well, he didn’t have to like the picture, but the one thing he couldn’t say was that the snowstorm was fake. He often makes errors like that. And I know I get angry with John Simon, who invariably has something terrible to say about some physical aspect of an actor. I happen to despise Barbra Streisand as a performer — in fact, everything I know about her makes me despise her — but it offended the hell out of me when Simon started writing about her nose. I don’t find Streisand’s nose the least bit unattractive, and I don’t think it has anything to do with her acting. I find that habit of Simon’s to be really disgusting.

After downgrading recent films of yours, such as Quintet and A Perfect Couple, New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael — once one of your staunchest admirers — wrote that “Altman wears his failures like medals” Did that upset you?

Well, I can understand where it comes from, but just because she and other critics generally dismiss a film doesn’t mean that I’m going to follow the pack. I don’t agree with them. I am still very proud of those films, extremely so. And if there’s something I’m not proud of, I don’t show it.

Has that ever happened?

Yes. There are some television shows I directed early in my career that I really wouldn’t want anyone to see. That kind of thing could happen again in the future, but it hasn’t happened recently. That doesn’t mean I think critics are crazy and that the audience is wrong and that everyone should understand each of my films. All I’m saying is that there’s an audience out there that will understand them and that I’ve been happy with the films I’ve made. When critics don’t like a film, it hurts my feelings, but I think it’s fair to say that the more adulation you get in certain quarters, the more criticism you’ll get and the more people will expect of you. It’s like people saying, “Oh yeah? Well, show us again.”

I think it’s great that critics write about movies, because otherwise you’d just put an ad in newspapers saying this is what we’re showing on Saturday night; so in a way, criticism dignifies what you do. But the problem even critics are facing now is that there isn’t a broad spectrum of movies to draw from anymore, and all the films you can see are pretty much the same. I really don’t think there’s any point in reading criticism of The Empire Strikes Back or Animal House.

You’re hardly alone in thinking that an increasing number of U.S. films have all the import of toothpaste commercials. What do you think is responsible for the recent surge of mindless American movies?

Let me state the problem in reverse: everyone’s somehow trying to make a fine art out of something that’s marketed as the very lowest form of exploitation, which is how movies are sold. The movie business is now a cheap carnival sideshow, and the only people who are concerned with the content of films are the people who actually make them. The people who sell films don’t think like that. Because the cost of manufacturing a movie is so high, studios care only about films that aim for the lowest common denominator in an audience. The studios want people to come in and sit there and not be intimidated by a film. They want moviegoers to totally understand a film and be able to laugh at it, so they keep dropping their films’ contents down to teenage levels and below, because that’s the age level where people want to like what their peers like.

It’s like when I was a kid. I thought baseball sucked, but the Yankees were the best, and if you weren’t a Yankee fan you were out of it. So it was the easiest thing for me, as a 12-year old, to go out and say,

“Oh, I love the Yankees.” This is what audiences are doing, and it’s also what the studios are doing. If I had any real sense, I would just not make any more films. I mean, I really shouldn’t; I don’t want to anymore. I should quit. But the other side of the coin is: then what do you do for the rest of your life?

Perhaps you just wait for the current wave of horror films and Animal House imitations to subside. In any case, it’s clear that movies are hardly better than ever. Why not?

I think a lot of it has to do with television, which is the nation’s educating tool. In the last five years, the quality of television has dropped at about twice the rate that it should’ve gone up. And that, of course, has educated — or de-educated — the public to the point where films are following the same course. Today, if people see a movie and think, “Jeez, I don’t understand what he’s doing that for,” instead of trying to figure it out or accept it, they feel stupid — and they are stupid. They are stupid!

I hardly do it anymore, but starting in 1970 I’d go to colleges and show films of mine, and I’d talk to audiences of students, most of whom were interested in film. Each year they would challenge me and tell me I was full of shit; they’d say, “I didn’t like this,” and “Why did you do that?” Now when I go to a college and stand up before 5,000 people, I can’t even get anybody mad at me. The kind of questions I get these days is “Who’s the most ‘fun’ movie star you’ve worked with?”

Another biggie is “Does Paul Newman really drink a lot of beer?” It’s like fan magazines or a gossip column, and it’s only because we’ve catered to the lowest possible part of our circus.

But there’s obviously a method behind all that madness. Frank Price, head of Columbia Pictures, recently noted that 75 percent of moviegoers are 30 years old or under. If that’s an accurate statement, can you really blame the studios for catering to a younger crowd?

Frank Price is one of the terrible people who are responsible for the way films are going. Guys like him sit around and look at a graph and say that the biggest audience for movies is made up of everybody under 30. Well, of course that’s true. People under 30 have a lot of money to spend and the most leisure time to spend it in. And they don’t like to stay home, and they don’t have that many places to go — you don’t have to be a genius to figure that out. But it doesn’t mean you cannot make profitable films for a discerning, intelligent adult audience. But the studios don’t want that anymore. They need the $100 million picture to make up for their failures. That’s become the criterion behind every picture: success. And that’s why I don’t go to the movies anymore. What is there to see? Why waste your time? Every once in a while I’ll hear about an interesting film and I’ll think, “Oh, God, a good one managed to slip through.”

Have the great Robert Altman actually had trouble slipping your movies through?

That’s happening right now. We have a film called Health, a political satire about presidential elections starring Lauren Bacall, Glenda Jackson, James Garner, and Carol Burnett. The film is owned by Twentieth Century-Fox, and we can’t even get their attention when it comes to getting them to release it. Their answer is “We don’t know how to sell this film. There’s too much in it. We don’t know what audience to sell it to, and we can’t find a hook to get everybody into theaters to see it.” They’re looking for one thing to advertise so that people will say, “Oh, we gotta see that.” Caddyshack was scato-logical; they knew people weren’t going to have to stop and think. People didn’t have to say, “What did that mean?” Health isn’t that kind of picture.

What can you do to change the situation with Twentieth Century-Fox?

Nothing. I have no options: they own the film. I could sue Fox for not making a proper effort, but my chances of winning such a suit are slim and none. I just give up.

Could you buy the film back from them?

Oh, if I came in and handed them $6 million, they’d sell me the film back. But I don’t think I’m going to get anybody to invest $6 million in a film that’s been bad-mouthed and is already a year old.

Before Nashville was released, Pauline Kael saw a rough cut of the film and her rave review helped make Nashville the most eagerly awaited movie of 1975. Could you do something like that for Health?

You don’t understand: that doesn’t mean a thing to them. You can’t even embarrass these people. I can say things about them that should cause me never to be allowed into their offices again, but they don’t even care about it. They’ve got accountants who say, “No, we’re not going to spend money advertistury — Fox finally released Health: The film opened in one theater in Los Angeles.)

As for Nashville, it was a very low-grossing picture, and I think Pauline’s review probably hurt the film because she overhyped it. I think Pauline blew the film up to such an extent that it affected the way it was sold. I mean, if you try to sell something as a masterpiece, you’re dead. In school, if a teacher talked that way about a book you’d say, “Oh, God, a classic. Do I have to read that?” But if the same teacher said, “Here’s a book about a mad dog in Alaska, and it has some dirty words in it,” you’d think, “Hey, perfect. This sounds like a terrific story.” Partly because of that, Nashville wasn’t successful compared with Animal House and those kinds of films. Nashville got a lot of ink and was very successful in Europe, as most of my films have been, but people in the South hated it, and it hardly ran there. Yet those same people went out and spent a fortune on Smokey and the Bandit and Walking Tall, which gave them a chance to watch Sheriff Buford Pusser crack skulls.

Penthouse: Your description of the movie business — along with the news that film attendance is down this year — would serve to indicate that it’s in bad shape. Is that really the case?

It’s in terrible shape. It’s at the point just before total destruction. It’ll be just like Broadway, which has become a joke. You no longer can take a viable piece of material to Broadway and really do well with it, because everything on Broadway is now geared to Long Island theater parties.

The same kind of thing has been happening to films over the last decade. It began happening when certain pictures grossed $100 million and when the conglomerates took over film studios. These companies make their money off ski lifts, soft drinks, hotels, and television. Right now, I can’t think of one person who’s running a studio who really understands — or likes — films. They’re merely managing a business. I can go in and talk to the president of a studio, and he’ll say, “Showmanship is no longer required. This is a dollar-and-cents business.” What it’s really become is an ugly business, and it used to be a nice, glamorous, attractive industry. No more.

Could part of the problem be a lack of talented young filmmakers coming along?

No, the talent’s out there. Think about the publishing world for a second. If the only books published were written by guys like Harold Robbins, an E. L. Doctorow would be back working as an editor again, because he can’t write that crap. My point is, when there’s no market, talent can’t surface, and that’s what’s happening in films. I mean, if Universal calls in a young director and says, “Listen, we’ll give you the chance to direct a film, but goddamit, we want it to be like Animal House,” what’s the guy going to do? Lie to Universal? Jeopardize his future by making the film he wants to make? Or will he make the piece of shit they want him to make? In any case, there are plenty of good young directors around.

For instance, I think Alan Rudolph is a terrific filmmaker. He’s got great potential and great integrity. I produced two films that he directed, Welcome to L.A. and Remember My Name.

How were they received?

Reviewers liked them, but financially both films were highly unsuccessful. He then finished a picture for United Artists called Roadie, which I haven’t seen. I was in Malta when it was released, and although everything I heard about it was great, UA pulled it out of release after a week or two, and now it’s gone — and suddenly Alan Rudolph is no longer a desirable film commodity. Meanwhile, I had a commitment to do a film with United Artists, but they reneged on it after Roadie. They said, “Look, we don’t want to make this kind of film anymore because we had bad luck with Rudolph.” So, because I sponsored a director whose film was unsuccessful, they’ve canceled me. They did it because they no longer want to make a film unless they know exactly how it’s going to turn out. They’re now terrified of doing that, and maybe they’re right; maybe my films wouldn’t make their costs back under the best of circumstances. That’s the dilemma we’re in, and that’s also the thing that keeps the lid on so that you can’t find the new directors.

Does the present state of the movie business ever make you long for the old Hollywood studio system?

Well, I never worked for a major studio when they had contract players, but at least those guys — the Zanucks, Warners, Mayers, and Cohns — took pride in what they did. They were absolute, insane monsters, but making movies was more than just a business to them. If they wanted to make a film and were told the public wouldn’t like it, then goddamit, they’d make the public like it. I think there’s some value in that. But believe me, it doesn’t happen anymore, at least not at the studios. Those old guys who once ran the studios may have browbeaten their people and treated their actors like dirt and also may have cheated them on their salaries, but they knew those people were their bread and butter, and they nurtured them and brought them along. Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart would never have made it as stars today, because nowadays if you don’t hit it right off the bat, you may never get a second chance. Back. then, a Jack Warner would say, “I don’t care what he thinks, get that mush-face Bogart into that goddamn picture, and if he doesn’t like it, suspend him!” People saw more and more of Bogart until he finally got a role that hit, and then the public’s confidence moved over to him, and he was a star.

Contrast that with what happened to Shelley Duvall: after I put her in Brewster McCloud, her first movie, nobody hired her again except me. Shelley Duvall’s done seven or eight pictures for me in the last seven or eight years, and we thought she’d finally become a major star when she got The Shining. That didn’t happen, but that’s still a pretty good credential — to have the lead in a Kubrick picture with Jack Nicholson. After Popeye, though, I don’t think there will be much question about her.

Popeye certainly seems like a departure for you. How did you happen to get involved in it?

Producer Bob Evans, as I understand it, came up with the idea and got Jules Feiffer to write the screenplay. A copy of the script was sent to my agent, Sam Cohen, for another client of his to read. The director in question, a very fine director, rejected it on the basis that he didn’t think it was right for him. Sam then called me and said, “Would you read this and tell me if I’m wrong? Because I think this is a great screenplay, and I can’t understand why people aren’t fighting to do it.”

‘I don’t go to the movies anymore. Why waste your time? Every once in a while I’ll hear about an interesting film, and I’ll think, “Oh, God, a good one managed to slip through.”’

Well, I read it, not to pass judgment on it but just for my own curiosity. Much to my surprise, I called Sam and said, “Really, I’d love to do it.” He called Evans, and we got together and went out and made the picture. Because of Robin Williams’s television schedule, we had to shoot the picture during January, February, and March, and after researching Florida, Mexico, Hawaii, and Australia, we chose Malta, built an entire sea village there, and then shot the movie.

When she returned from filming in Malta, Shelley Duvall characterized the film as “a morality tale.” Is it?

If you’ve read the original Popeye, you can see that it is a morality tale, and it’s a familiar theme in pictures for me: Popeye is a stranger, an orphan who comes into this sea village, looking for his father, who deserted him when Popeye was two years old. He’s an outcast, and the community he comes into is oppressed by a dictator. People have never seen the dictator, but they live in fear of him, and suddenly here’s this character who shows up and says a man should stand up for his rights.

Our Popeye is not the animated cartoon. He’s the comic-strip Popeye created by Elzie Segar. He’s a character who says “I am what I am,” and he won’t be pushed around. It’s a very simple film that deals with basic human emotions and political ideals that really go back to ancient Greece.

You usually cast your own films. Were you at all reluctant to work with Williams, who’d never made a movie before?

I don’t think I would have done the film without Williams, because I wouldn’t have known who else to cast as Popeye. I did choose Shelley Duvall. When I came into the thing, most of the talk was about Gilda Radner, who I rejected, but that was just people thinking, “Oh, she’s hot, she’s Saturday Night Live, so let’s protect our investment.” But Shelley was a perfect Olive Oyl. She and Robin are superb in the film.

A number of Hollywood observers believe that Popeye will turn out to be the biggest, most commercially successful film of your career to date. Do you feel that way about it?

Well, it’s a tacky little film, as a matter of fact.

A tacky film?

It is. The only thing that makes it a big film, other than being expensive because of the logistics involved, is that it’s a big, presold thing. I daresay that if Evans, Feiffer, and I had had the genius — which is what it would have taken — to start from scratch and create the film that exists now, it would have fallen into the category of being understood by a very, very elite few.

I think that if there had never been an Elzie Segar and a Popeye comic strip, the film would have failed commercially, because people would have said, “Well, what the hell is this? What is it supposed to be?” They’d have no relationship to this fantasy. But because Popeye has a presold audience, it isn’t going to be hard to get people into theaters to see it, and it gave us the chance to do what we wanted with the picture. I mean, there are some marvelous moments in this picture. But if people had no pre-knowledge of Popeye, and if we had created this kind of comic, clownlike place, people would really claim it as a masterpiece — and it would be! So what you have to say is that the genius in the piece is Segar’s, and if we succeeded in making Popeye really good, it’s because we took Seger’s idea and, let us hope, did it well.

Popeye could very well turn out to be a continuing film character, like James Bond. Are you planning to direct a sequel?

No, I’m not. They’re making sequels to everything. I mean, I expect to see a sequel to The Day the World Ended. My own history is that after a logistically difficult film, I try to do a simple little film dealing more with people and contemporary things. I kind of feel that after Popeye I’ll probably go somewhere in America and do a nice film where I can shoot on location, rather than build sets.

In a recent Penthouse interview, Charlton Heston said he feels that one of the problems with current movies is that they’re usually about victims, not heroes. Do you think that’s true?

Well, I think traditional kinds of heroes came at times when there were frontiers. By that, I don’t mean locales but new areas to cross, whether in medicine, law, architecture, or art. Today, I think a hero is someone who’s a victim — and who chooses to rise above that. And I don’t think the success of his effort is what makes him a hero; I think it’s the desire to rise above being a victim. In McCabe and Mrs. Miller, I thought McCabe was a hero. McCabe was dumb, and I doubt that he had the IQ to be a hero, but I bet he had the heart to be one. The fact that he failed makes him no less a hero than Popeye. I did a film about Buffalo Bill a few years ago, and I think he was a hero, who unfortunately got mired down when he started to believe his own publicity. And the Essex character in Quintet was also a hero.

Buffalo Bill and Essex were both played by Paul Newman, which brings up an interesting point. By now it’s fairly common knowledge that any number of well-known actors are willing to accept less than their usual film salaries in order to work with Robert Altman. What do you think is responsible for that?

I think I give them respect and credit for being intelligent. I admire actors, and I feel they’re the most important element in a film. I’m not an actor, and I could not be an actor; I just don’t know how they do it. I ask actors to contribute artistically to a film, and I do that for a selfish reason: to get the most input from them that I can. If I hire talented actors, I want to use as much of their range of talent as possible and not limit them to what I think. Most actors enjoy working with me, but that’s not true of all of them.

Why not?

Well, because of my reputation they may come into a film expecting some magic to happen, and instead they’ll wind up thinking, “Gee, this guy doesn’t even know what he wants.” A lot of times I’ll work with actors who I know are highly talented because I’ve seen their work on the screen, but I won’t be able to communicate with them at all. I can look into their eyes when we’re talking, and I’ll know they think I’m crazy. For some reason, there will be a communication gap, and I don’t think it’s their fault; if anybody’s to blame it’s me, but I don’t even think it’s my fault. It’ll just be one of those cases where two people don’t connect.

“The movie business is in terrible shape. It’s at the point just before total destruction. It’II be just like Broadway, which has become a joke.”

Actors in your films often wind up writing a lot of their own dialogue, which in the past has caused you a lot of problems with certain screen-writers. Why do you do that?

I take the position that a script is like a guide or an artist’s rendering and that you make changes within it as you make the film. Screenwriters are told or taught or propagandized to believe that, by God, they write the screenplay and directors should go out and shoot exactly what they write. Well, I was the original author of Images, Three Women, and Quintet, and speaking as both a writer and a director, I don’t agree with that. Film is not a medium where a person sits down and reads something and that’s the end of it. In movies the writer is part of the construction process. He’s one of the engineers. He does a sort of blueprint, and then these other people come in, and we build a building. You start out with a screenplay and say, “This is what I want,” but by the time you put ten actors into it, it has to change a little bit to get the most out of the actors.

Why not get the most out of your writer?

Let me use M*A*S*H as an example: Ring Lardner, Jr., who wrote the screenplay, got very angry at me because he’d written Hawkeye Pierce as a guy from Maine, and Ring was very meticulous about the New England speech patterns and expressions that Hawkeye used. Well, we hired Donald Sutherland, a Canadian, to play that part, and he wasn’t comfortable with a lot of that dialogue, so I immediately changed it to fit what Donald was comfortable with. Ring got very mad about that, because he felt that an actor should be good enough to act a part as written — and Donald is good enough to do that. But to me it didn’t make any difference to the story we were telling whether Hawkeye was from Maine or not. There are so many other things that will also cause you to alter a screen-play, and they include the locale, the weather, the shooting schedule, and the budget.

Probably the most accurate description I can give you of the moviemaking process is that it’s like building a sand castle. You go down to the beach, and you decide to build a sand castle, and you call some friends in to help you. At least I do: I wouldn’t build a sand castle alone. I’ll get as many friends together as I can, and we’ll start working on it, and if some stranger comes down to the beach, I’ll say, “Hey, you want to help?” And then we’ll work our asses off and somebody’ll do the moat, and somebody else will do the windows, and it’ll turn out that the sonofabitch is no good at windows, so we’ll get somebody else to do the windows. Then, just when we think we’re about done, a big piece of the sand castle will cave in, and I’ll get pissed off and wonder why I started the goddamn thing in the first place. But finally you finish it, and you’re happy about it-and then the tide suddenly comes in and washes it away, and you say, “Okay, we did all right, and it was fun. Let’s go have a few beers.” Making movies is that kind of experience to me.

After filming The Long Goodbye, you said that Raymond Chandler’s plots served only as an opportunity for him to present a series of thumbnail essays. Do you think that might be true of your own work as well?

Sure it is, and I also think that several of my films could be described as essays. For instance, I’d always wanted to do a film on gambling, and California Split gave me an opportunity to delve into that world. I think it’s a very good film, and that there’s a certain documentary quality to it. Matter of fact, when it was edited for television, almost all the parts with the girls were cut out of it, and most of the language was censored for TY as well; anyone seeing it for the first time had to believe they were watching a documentary about gambling. But they also had to wonder what George Segal and Elliott Gould were doing in it, because there was absolutely no story left when the censors finished chopping it up.

Why do film studios allow their movies to be treated like that?

Because it’s a by-product they sell, and they just don’t care. A Wedding was mutilated even worse than California Split; the TV version of that film had nothing to do with the movie — and I mean nothing! In prime time the networks censor language, and syndicated TV sales are worse, because that’s when a movie runs into local stations and local blue laws. It’s a horrible situation. The one guy who’s really been smart about all this is Woody Allen. He won’t make a picture unless there’s a clause in his contract that says the film can never be sold to television. He makes less money up front because the film company has to figure in their loss of TV rights, but that’s his deal, and more power to him.

Have you talked to film studios about how you’d like your movies shown on television?

Sure I have, but there’s really no talking to these people. You make an appointment for a meeting, you show up — and they don’t listen to what you say. They don’t want people like me there, because all we do is inhibit them. I’m sure there are some good guys at the studios, but if they’re there, I haven’t met them.

Faced with all this adversity, can you still get excited about making movies?

Oh sure, because they’re different each time, even down to the technical things, like trying for a new effect or seeing a landscape and envisioning what you’re going to put into it and how it’s going to look on film. And I still find it amazing to watch actors transform themselves into characters before a camera. It’s always exciting. I can look at something and say, “How do you do that?” and that’ll be enough to get me started on a film — the fact that I don’t know how to do it. Popeye was like that, it intrigued me because no one knew what it would look like as a film. It’s really hard to explain this, because it’s almost like trying to describe a dream. It’s vague. There are too many veils there, but you know something’s behind it, even though you’re not quite sure what it is until you do it.

Do you see yourself as a catalyst — someone who brings a cast and crew together and then helps cause a kind of magic to take place?

Well, I call it releasing the pigeon — once you let it go, then everything goes. You know something’s going to happen, and something will happen. That’s also the way I choose my films. I don’t try to be a barometer of the times and say, “Oh, this would be a good subject to deal with now.” Instead, somebody will tell me, “Gee, the other day I was out driving, and I saw three power and — light trucks stopped on the highway, and five guys were taking a coffee break, and up on this electric pole, splicing some high-tension wire together, was this girl with a hard hat on and hair down to her ass.” That’s roughly the way I started investigating the subject of women who work in blue-collar jobs and why they do it. More than likely, that will be the next movie I’ll do.

When a subject like that interests me, I’ll ask questions of myself to find out what my misconceptions are about it, because I generally tend to think the same things most people think. I’ll agree that some guy’s an asshole and another one’s a jerk because of what I’ve read in newspapers, and on Power & Light — which is what we’re planning to call the film — I know that my own first impressions were “Oh, they’re probably just a bunch of dykes.” You find out what your own prejudicial thoughts are, and then you go out and discover what the truth is, and that’s really a fine experience. I know once a project gets going I’ll suddenly start seeing articles about female blue-collar workers, and maybe I’ll start hearing piano music, for instance, and I’ll start looking at pianos. And the next thing I know I’ve got one of these girl electricians as a piano player. It all comes together.

That sounds as if your subconscious eventually lets you in on what you’re thinking.

It does, and you have to trust it. In a lot of areas, I really tell myself, “I can solve this problem by going to sleep tonight.” And that will turn out to be true, which is why people say, “Let’s sleep on it.” You let it come out. I think I’ve hated every film of mine the first time I’ve seen it, but I don’t get into a panic about it. After seeing one of my films, I’ll go to sleep thinking about it, and I’ll literally stay in a halfway dream state all night long. And I know that I’m going to put my finger on what the problem might be and that it will be solved. The answer’s going to come, probably by morning, and if I haven’t come up with the solution, at least I’ll have the confidence to know that it’ll be there soon enough.

“The movie business has really become an ugly business, and it used to be a nice, glamorous, attractive industry. No more.”

You’re saying that you never enjoy your films the first time you see them?

Oh, it’s a terrible experience. The first time I look at one of my films, I’ll think, “Oh, shit!” because there will be a lot of things in it that I don’t like. But that’s part of making pictures. I think the real value of making a film is to look at all the dailies before they’re edited. The people who work on a film go in at the end of the day and look at all the footage. And you see the mistakes and the good things, and you see everything repeated many times, and pretty soon it’s all in your mind like a Thomas Wolfe novel. But then the film progressively gets worse as you refine it, because you’re progressively getting it pared down to where uninterested parties will become interested in it. But that’s probably necessary — unless you were part of the company when we made Buffalo Bill and the Indians, it would bore you to death if you were to watch four hours of Sitting Bull’s entrance.

But finally, when a film is finished there’s an obligation to the people who made it to get it released, to get it seen. That’s why I feel the way I do about Health, for everyone involved in it — from the cast to the art director to the old people in Florida who were extras — went into the movie blindly. They didn’t have control of all parts of that film. I did. Well, as long as the film isn’t seen, somewhere in his mind that art director, for example, is going to have his doubts about whether or not he did his work well.

Doesn’t it bother you in the same way?

No. It would have years ago, but I have a lot of barnacles on me. If I did a film and I couldn’t find one person on earth who liked it, I guess I’d never do another one. But if I can find one person who’s seen one of my movies and who says, “Jesus, I walked out of the theater and didn’t eat for four days, and your picture was all I could think about, so I went back and saw it again,” well, that’s enough. That’s really all that’s necessary. I’ll know it’s good because a guy in Dayton, Ohio liked it, and that’s a man who would know. My ego can adjust to that, and so can everyone else’s. That minor response is fine, because at least you know you’re not shouting into space.

Movie executives would undoubtedly reply that even low-budget films now cost several million dollars to produce and millions more to advertise. Faced with those hard facts of life, can you realistically expect the studios to finance films that have a limited audience at best?

They have to! They have an obligation to do it. They’re resisting that obligation right now, and if they continue to do so, they will have destroyed much of the audience they hope to draw from. Going back to Charlton Heston’s comment, I want to say that it’s my responsibility not to be a victim and to protect the victim, which in this case might be films and the people who make them. I don’t know how to explain it, but there are some things you just have to do, or else everything you’ve done is worthless; it would be like saying that I don’t really care at all about films and I never did care. Look, I have done films that people have responded to, and I’ve seen people change as a result of films they’ve seen. It’s like I really got to those people, like I wasn’t trying to reach them but I did reach them.

And that’s the only reason for making films. Making money is not the reason to make films, but people who do it only for money cannot understand that. But somehow, those old guys who once ran Hollywood understood it. They also knew that actors would probably work for nothing, because they love their work. You want to know something? The guys who are running the studios today don’t even know that!

You can take a look at the Filmography of Mr. Altman, and see why we believe he should have won Best Director awards a few times over the years. Of course you can also read an early interview with Burt Reynolds in these pages as well. He might not have deserved so many Academy awards, but golly he could be fun.