Penthouse talks with Russell about his newest projects, and his long career.

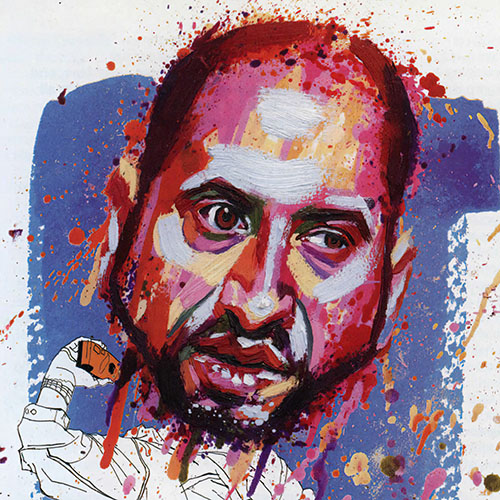

Leon Russell: 50 Years of Music

A Poem is a Naked Person, a never-released documentary about Leon Russell filmed from 1972 to 1974 that had achieved near-urban-myth status, finally had its world premiere at the 2015 South by Southwest film festival.

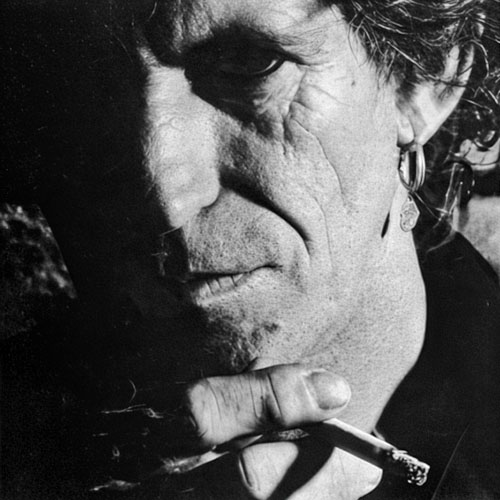

Leon Russell famously sang about his life “up on a tight rope” (“One side’s hate and one is hope”) in 1972, but the life of the Oklahoma native — architect of the “Tulsa Sound,” and a member of L.A.’s famed Wrecking Crew session musicians — has been up and down in recent years. After making his mark with a raft of hits as both a solo artist and a sideman for rock royalty, Russell hit a low spot in 2009 — until Elton John, a lifelong fan of Russell’s greasy, soul-and-gospel-based piano style, called him to suggest they record an album together. Their collaboration yielded The Union, which was nominated for a Grammy in 2010.

Since then, Russell has survived some alarming health problems and celebrated his 72nd birthday with the release of his 37th studio album, Life Journey, a look back on his long career. “This is a record of my musical journey through this life,” he says. “It reflects pieces of things that I have done and things I never did. Nearing the close of my adventure, I feel that I may be the luckiest guy in the world.”

I caught up with Russell at his English-style home and country estate outside Nashville and was surprised at the silver-haired legend’s sense of humor, given his often-grumpy demeanor. “When they first asked me if I would do an interview with a girl from Penthouse,” cracked Russell, who’s been married for a quarter century, “I said, ‘I’ll only do it if we’re in the nude.’ The truth is, I can never be naked in public, or my fan base would disappear immediately.”

Still, I had to ask, which is better: Love or sex?

Russell: “Both. They’re good if they can both happen together. But you can’t have everything.”

Elton John was the executive producer on Life Journey. How involved was he with the process?

Russell: Well, he wasn’t there. and he didn’t make the record. But he paid for it, and he insisted that I get a producer, which ended up being Tommy Li Puma. [Tommy and I have] known each other a long time, but we never really did anything together, so I asked him if he’d be interested, and he said, yeah, he would.

A number of the songs — Robert Johnson’s “Come On in My Kitchen,” “Fool’s Paradise,” and your own “Down in Dixieland” and “Big Lips” — sound like you could have recorded them in 1970.

Russell: Well, all the stuff that I record sounds the same. I only know how to do it one way. When we started out doing this, Tommy and I had a lot of conversations. That was his method of discovery, I suspect. And I just happened to mention that most of the time when

I was playing the ensemble on the piano, I was imagining the [Count] Basie band playing that ensemble. I’d play some little melody lines in between, but it was all based on Basie, my fantasy. And lo and beyond, when we made the record, Tommy showed up with [John Clayton] one of Basie’s writers and conductors and bass player, so it was exciting for me.

How did you choose the songs?

Russell: I basically played Tommy songs that I knew. I cut another standards album a few years ago [2002’s Moonlight & Love Songs] and had this great [chart] writer, and told him I kind of wanted it to sound like Disney music that was complicated, but you couldn’t really tell it was complicated. But it turned out to be so complicated I couldn’t play on it. And I expressed my concern to Tommy about that for Life Journey, and he said, “Well, you can play the songs and make the demos for the writers, and they’ll write ’em to your chord changes,” which made it a lot easier for me. A lot of the songs I’d played many times for singers, but I’d never sung ’em before, like “The Masquerade Is Over.”

Does that song mean something to you?

Russell: I used to go out to these jam sessions at this jazz club in Tulsa, and they played that song all the time. There was a hillbilly band, Leon McAuliffe, and three or four of the guys worked in that band. They were all quite proficient jazz players. That’s where I learned that song, and that’s what actually gave me the idea for writing the song “This Masquerade,” which Tommy cut with George Benson — and which sent my kids through school. So there are a lot of weird connections with this album.

Your real name is Claude Russell Bridges. Did you choose “Leon” from Leon McAuliffe?

Russell: No, actually, I had a Sunday-school teacher called Leon Meigs. I used it from there. And when I was 17, I went to L.A. I graduated from high school in ’59, and I went out to California the week after I graduated. But I wasn’t old enough to play in the nightclubs in California, and I was starving. I’d been working in nightclubs for four years at home, because Oklahoma was a dry state and they didn’t have any alcohol laws. They had lots of alcohol, but no laws. Anyway, out in L.A., I had to borrow a friend’s ID. He happened to be a Cajun guy, Leonal Dubrow. Some people were calling me Leon, and some people were calling me Russell, so I just chose Leon Russell. By the way, the week that I turned 21, I got my first real session. And then the next week I had two sessions, and the next week I had three sessions, so I didn’t have to go into the nightclubs anymore anyway. Isn’t that the way it always is?

You have a heavy gospel influence in your music. Where does that come from?

Russell: Well, when I was playing those nightclubs at about 13 or 14, I was playing piano in the Methodist church. But the Methodists are a little bit starchy.

I had this little crystal set [radio] that I made, and the only station it got was rhythm and blues and gospel. I started playing some of that in the Methodist church, and they ran me off. So that’s where that comes from — the radio.

You recorded your parts for Life Journey on an acoustic piano, after spending many years playing an electric instrument. Why?

Russell: I quit playing wooden pianos years ago. I had a birth injury that gave me a slight paralysis on my right side, so I’ve always had to put up with that. But I play a vocabulary on a wooden piano that I don’t play on the digital piano.

The late John Hartford once told me, “Style Is based on limitation.” So many definitive stylists came to their work from some sort of limitation that they made work in their favor.

Russell: That’s absolutely true. I was fascinated when I realized that. In fact, I was talking to Tommy about it. When I first met him 45 years ago, he could just barely walk. He used two canes [from a bone infection in childhood]. He was walking somewhat better when we did this record. We were talking about that, and I said, “If I hadn’t had that birth injury, I’d probably be selling insurance in Paris, Texas.” And he said, “Yeah, and I’d be cuttin’ hair in Cleveland.”

How did this birth injury occur?

Russell: Well, I’m not sure. I wasn’t really lucid at the time. But I expect that the doctor was pulling me out by my head, and it damaged the second and third vertebrae in some way. Spinal injury.

It affected your whole right side?

Russell: Yeah. When I walked, I had to really concentrate on it to make it look like I wasn’t limping. I had to concentrate a lot on any kind of muscular stuff that I did. It may have had something to do with my songwriting, because I had to try to figure out if I could play it or not.

You don’t smile a lot. Did it affect your face as well?

Russell: I’m sure it did, but I was just trying to copy Earl Scruggs with all my facial movements. Onstage, he didn’t have much expression. But whenever I talked to him, he was a veritable store-house of bluegrass information. He would just go on and on and on.

There’s a clip on YouTube of you singing “Jambalaya (on the Bayou)” as part of the house band for the 1960s TV show Shindig.

Russell: Yeah, I played on that. Jack Good was the producer of that show. I felt he had a real odd taste in music. He wanted me to sing more on the show. He also wanted to photograph me walking up a ramp, so it would accent my limp. Kinky British, you know what I mean?

I don’t know that I would have recognized you until I heard you sing.

Russell: Well, I had a Jay Sebring haircut.

What inspired you to grow your hair and beard out?

Russell: I was late for a session one time, and I didn’t have a chance to comb my hair and spray it and shellac it, so it was hanging down. I worked with a lot of the same people every day, and I had so many people come up to me and say hateful stuff to me, and it amazed me. So I thought, “Well, I’m just gonna look like this all the time, because I want to see what people really think.”

You’ve worked with just about everyone, including George Harrison, who played on your debut album in 1970.

Russell: George was so great. I visited him over in England, in Henley-on-Thames at that castle he lived in. He gave me the tour. There was a dungeon down below the house, and as we walked down, there was this tunnel with caves on the side. He made us put galoshes on, and I thought, Well, that’s weird. But there was this creek that ran down the middle, and I followed him out, and there was this pond, about an acre and a half. And he just walked out on the water! The joke was that the water was only about an inch deep.

You played on Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night.”

Russell: I played on several Sinatra sessions. Kind of frightening, because there were never less than ten California troopers there. Of course, it was long before drive-by shootings or anything like that. But there were a couple of doors to the studio, and there were two [troopers] at each door, and two or three inside, and two or three outside. It made me a little bit nervous.

As part of the Wrecking Crew session players in the 1960s, you worked with Phil Spector a lot.

Russell: When I met Tommy [Li Puma] at Liberty Records, he was promotion man there. I was making demos for Jackie DeShannon, for Metric Music, and I ran into him over there. Jackie introduced me to [arranger/producer/ songwriter] Jack Nitzsche [Specter’s right-hand man], and Jack was the arranger on the Phil Spector records. He used me on those sessions. Phil didn’t have much of an opinion of his audience. When I first went in the studio, he made a cross of his fingers and said, “Play dumb! Play dumb!”

Were you surprised when Spector was arresting for shooting Lana Clarkson?

Russell: Well, I knew he always carried a gun with him. I’d heard that he shot a hole in the ceiling at A&M. There was a little Napoleonic stuff going on there.

In the documentary film The Wrecking Crew, Cher tells a very funny story about you. She says you came to a session completely drunk, doing all this crazy stuff, talking a mile a minute, and being really hilarious. And Phil wanted to begin, and he said, “Leon, have you ever heard of the word ‘respect’?” And Cher says you jumped up on the piano and said, quite enthusiastically, “Phil, have you ever heard of the word ‘fuck you’?” And everybody just fell on the floor laughing, tears rolling, because it was so out of character for you.

Russell: The way she tells it is absolutely true. Except Phil might have said “teamwork” instead of “respect.” But yes, that’s what happened. I’d been out with Glen Campbell, I think.

How’d you hook up with Joe Cocker?

Russell: I ran into [English producer] Denny Cordell, and he brought me out to play on some Joe Cocker records, and I thought it would be a chance to maybe pitch some tunes. So after the session I played Joe a couple of tunes that he actually cut, “Delta Lady” being one of them.

That launched you as a commercial songwriter, but then you organized and performed on the “Mad Dogs & Englishmen” tour with Joe in 1970. That was one of the most exciting events of the era. Did it seem that way when you were in the thick of it?

Russell: Those were the kind of rock-n-roll shows that I saw at the Tulsa Civic Center when I was 15 or 16. It was called “The Lloyd Price Show of Stars,” with the Lloyd Price Band, and it was 25 pieces. And on the same show they’d have Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Anthony and the Imperials, Ruth Brown … like, 20 acts. And they’d come out and do a song or two and leave. And that was my idea of what a rock-n-roll show was. I never did see that anymore when I got to be an adult. That’s what I was trying to do.

Somebody asked you about Joe Cocker in an Interview, and you said, “I love bipolar people.”

He had his bouts with that, I think.

Did things end badly with him?

Russell: Actually, it ended quite successfully, I thought. But within the next couple of months, I started getting a lot of bad press about how I had taken advantage of him. As a matter of fact, when we were doing the show, Denny came up to me one day and said, “You know, you’re going to be accused of career profiteering.” I said, “What the hell is that?” He said, “Where an unknown guy takes advantage of somebody’s fame for his own use.” I said, “Oh, wow, complicated.” I just kept thinking that Joe was gonna step forward and say, “All the stuff that they said in the press isn’t true. That’s not what happened.” But he never did. So maybe he thought that, too. He was drinking a lot in that time, and I heard stories of him passing out in shows.

There wasn’t a big blowup?

Russell: No. The closest we came to a blowup was when we were rehearsing at A&M, that old Charlie Chaplin soundstage that Herb [Alpert] and Jerry [Moss] had bought. I was acting like the band leader, which I was. And I said to Joe, “Does that sound okay to you?” And he said, “It never sounds okay to me.” I said, “Oh, well, in that case, I’m not going to ask you again.” Which I didn’t. I just went ahead and did it. I didn’t quite understand that response.

Your relationship with Elton John is one of mutual musical admiration. But you’re also friends, right?

Russell: Well, when he called me and asked me if I’d like to do an album, I hadn’t spoken to him in 35 years. But I guess we’re friends. Denny and I tried to get him for Shelter Records when we started the label, and we just missed him by a couple of weeks. There weren’t many white soul singers around in that period, and I liked the way he sang.

When you were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, you said, “Elton came and found me in a ditch by the side of the highway of life.” Yeah, I was watching a soap opera. He originally called up when he was doing some shows with Billy Joel, and he asked me to write some songs. And I said, “Well, what kind of songs do you want?” And he said, “Up-tempo, baby!” I tried to write some stuff, and then he called back and said, “Let’s do an album together.” It was pretty exciting for me, and I was grateful.

And then right at the start of your collaboration, you had a health scare, a brain-fluid leak.

Russell: Well, I’d had it two or three times. I’d only been out of the hospital from the last operation out in Santa Monica about three or four days when we were supposed to start.

You’d had operations each time?

Russell: Yeah, that was the third operation. It was some kind of malformed brain pan up in the upper sphenoid sinus. They didn’t go together right, and it made a huge space. I had the first two operations done at the Mayo Clinic. The first one lasted for about a year or so. And then the second one lasted about a week, and then it all came back and got a lot worse. My wife found these Indian guys at St. John’s hospital in Santa Monica. They said, “What’s wrong with him?” She said, “He’s got a spinal-fluid leak running out of his nose,” and they said, “Oh, you have to come down tomorrow.” They did it the next day. They had the whole team, and they put a television camera up my nose and repaired the hole in my brainpan. So I’m on borrowed time.

How do you know when you have a brain-fluid leak?

Russell: Well, when you hit the brakes on your car, and this huge amount of fluid flies out of your nose and hits the windshield, that’s one way to know. Sometimes I’d bend my head over and my nose would run like a faucet. So I went to 14 ear, nose, and throat guys, and they all gave me sinus medicine. I’ve been lucky. It’s a rare situation, apparently. It doesn’t happen very often.

You’ve had heart trouble, too?

Russell: I’ve had a heart attack or two. The first time they put four stents in, and two weeks later I was sitting in a chair and I felt like I had a huge woman sitting on my chest. And so I went back again, and they put three or four more stents in there.

Have your health problems affected your desire to continue working?

Russell: Well, with my debt package, I’ll be working until the end of time. I had this assistant and bookkeeper who stole huge amounts of money from me. And my first wife came back after 35 years, so I had to go through a re-divorce, and it cost me a lot more money.

How do you get re-divorced?

Russell: I don’t know. I thought it was all over with, but apparently it wasn’t.

You’ve been doing another tour.

Russell: I haven’t stopped working in 45 years. It’s just that people are more aware of me at some times than they are at other times.

You’re talking to the audience at your shows now, which you never used to do.

Russell: Yeah, I never did. But I just had terrible stage fright. My wife said, “You need to talk at your shows. People want to hear you talk.” Well, I started doing that, and now they can’t shut me up.

I get up and tell those stories every night, and people cry.

You’ve been in Nashville for two and a half decades, but I never hear anybody say they see you around town. Do you venture out much?

Russell: Yeah, but I’m not in the mainstream. I kind of slink around.

As long as you’re going to work forever, what do you still want to do?

Russell: What is there left to do, you mean? I’ve thought about industrial plumbing. That might be interesting.

History gives us very few musical artists that appeal across generations, and Leon Russell definitely falls into that category. Obviously YouTube can open up a wealth of experience should you not be familiar with his work. Consequently, we recommend that as a place to start if you need one. You can even see the entire “A Poem is a Naked Person” documentary there, should you be will to plop down four bucks for the HD version. If you make your own coffee one morning instead of buying, you will find this to have been a worthwhile trade. You will even find a great “about page” on a site bearing his name. Even though he died in 2016, Leon’s diverse talent lives on. … Nice.