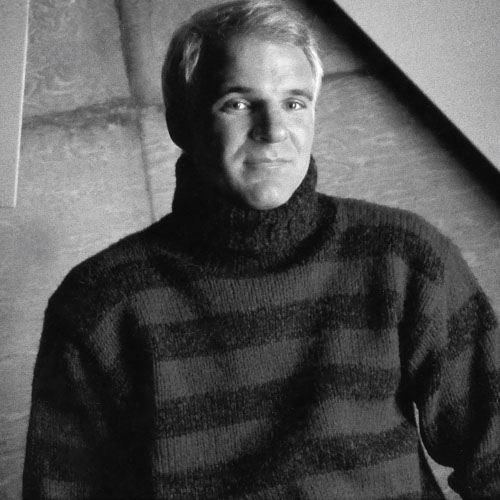

Steve Van Zandt’s performing career goes back to 1974, when he conducted the soulfully cool Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes with friend Johnny Lyon.

Then he hooked up with Bruce Springsteen for the Born to Run album, beginning a seven-year association with the Boss as both touring-band stalwart and coproducer of the best-selling The River and Born in the U.S.A.

In 1982 Van Zandt decided to pursue a solo career, Adopting the name Little Steven, he opted for the personally rewarding but financially suicidal world of making politically charged albums. Zeroing in on the apartheid practices of South Africa and the U.S. government’s dubious involvement in the politics of Central and South Americas. In 1985 he established the Solidarity Foundation, to promote the sovereignty of indigenous peoples, and Artists United Against Apartheid. The latter group, which included such performers as Bob Dylan, U2’s Bono, and Run-DMC, recorded a tune called “Sun City” that played a key role in calling the world’s attention to South Africa’s horrendous policies. For his efforts in that endeavor — and for his championing of human rights worldwide — the United Nations and Bishop Desmond Tatu paid tribute to Van Zandt in 1986.

After a ten-year recording hiatus, little Steven has returned with a vengeance with his latest solo effort, Born Again Savage, a blistering tour de force of guitar driven rock, propelled by the high-voltage rhythm section of the U2’s Adam Clayton on bass and Jason Bonham, son of legendary Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham, on drums. Van Zandt is also back on the toad with Bruce and the E Street Band and gearing up for a third season playing hit man/strip-club manager Silvio Dante in the acclaimed HBO series The Sopranos.

Penthouse caught up with Van Zandt during a break in the Springsteen tour. Funny, intelligent, and totally passionate about his work, he talks about The Sopranos, his buddy Bruce, his own new record, and the state of rock ‘n’ roll today.

Your latest record, Born Again Savage, definitely sounds like Little Steven, yet it reminds me a lot of The Yardbirds, Led Zeppelin, and The Who. Was that a conscious effort?

Yeah. That was the idea.

What was the thought process behind the record?

Musically, it was the first time I was able to find a way to do a traditional rock record and maintain my own identity. That was quite a challenge, and it was something I had never even attempted before. Ever since I started, I’d felt we needed to do a hybrid type of sound to be original because I respect traditional rock so much. I didn’t want to do something mediocre. I wanted to do something that was up to those standards. And I didn’t feel that it was possible to meet those standards in a traditional sense [ using just] guitar, bass, and drums. I thought everything great had been done. I really did.

So right away [with earlier records], I would incorporate R&B and soul and blues and rock and world music, and use all kinds of combinations, and find my own identity that way. But with this new record, I finally found a way to meet those traditional rock standards. And I did want it to be a bit of a tribute to the hard-rock people I grew up with. They meant a lot to me, starting. with The Kinks and The Who and The Yardbirds. With The Yardbirds, suddenly the guitar player emerged as the center of the rock universe, and that was a new development. Eric Clapton changed everything. People started going to see The Yardbirds because he was so extraordinary and he was doing something brand-new, really. So when he leaves The Yardbirds, in comes Jeff Beck, and he’s amazing, and then when he leaves, in comes Jimmy Page, and he’s amazing also. And then [those guitarists] went and formed, as you know, Cream, The Jeff Beck Group, and Led Zeppelin. And then Jimi Hendrix would become the fourth and final guitar god. But I wanted to do that. I wanted to structure the songs and arrange them so that the guitar was featured. And I’d never done that. I never played this much guitar on a record.

The songs have a healthy, fat sound, which you don’t really hear on records anymore.

No, you don’t. I despise digital technology when it comes to music. It’s the biggest scam that’s ever been perpetrated upon the American public. I keep my stuff analog till the very, very last phase, knowing that when it gets to the digital stage, the sound is going to be reduced. So I keep it as fat and healthy as possible. And it absolutely makes a difference. My record sounds warmer and bigger and fatter than most records because of that.

The theme of the record is religion. What prompted you to head in that direction?

It’s a subject that has always intrigued me. Who knows why, but it just does [laughs]. I love reading about religion and spirituality, and I find it endlessly fascinating. Even though the music on each of my five records is very, very different, the lyrics are very, very connected. I outlined five themes, and I stuck to them, and the idea was to at least have an idea of who I was at the end of the five. That was the point.

But I left religion till last because I knew it would be the most personal and the most complex. [Born Again Savage is] the most subtle, politically, even though all five records are political records. It deals with the political consequence of spiritual bankruptcy. But, lyrically speaking, it’s a little more gray than my typical political records. I try not to be rhetorical, but when it comes to politics, my lyrics tend to be a little more black and white because there’s a more easily defined right and wrong. Religion is not so clear. It’s a little more complicated.

In terms of spirituality or religion, what do you embrace?

I tend to focus on the common ground among all the religions. I take what I feel works for me, wherever I find it. I feel probably closest to some of the more primal religions — Taoism, some Buddhism, some Hindu, some American Indian. And essentially my religious beliefs come down to two things, which I learned in science class in the fifth grade [laughs]: All matter is in motion, and for every action there is a reaction. All matter is in motion means everything is alive. For every action there is a reaction means everything is connected. Those two things are the essence of my spiritual beliefs. As I say on the record, I don’t think religion is something that can be inherited from your parents. I think it’s a very personal thing that one needs to work at and think about. You have to dig deep inside, look around, and do some research. I think it would be helpful if the organized religions spent more time on the common ground rather than on our differences. It’s all the same: Be good to each other and respect each other.

When and how did you hook up with Bruce Springsteen?

It was around 1965 and we were on a circuit. The baby-boom thing was just peaking, and there were a whole lot of 14-, 15-, 16-, and 17-year-old kids, and a whole new teenage culture was being built around them in the form of beach clubs and teenage nightclubs. One of them was the Hullabaloo chain of clubs, named after the [sixties] weekly television show. Anyway, there were three Hullabaloo clubs in New Jersey — oddly enough, in Middletown, where I was from; in Freehold, where Bruce was from; and in Asbury Park. They formed this sort of triangle of a circuit, and Bruce and I just ran into each other. If you had long hair in those days, you were friends. If you were in a band, you were friends. If you had both long hair and were in a band, you were best friends. And we’ve been best friends ever since.

Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band were at the height of their popularity in the early 1980s, yet you bowed out to pursue a solo career. What prompted that gutsy move?

I felt I’d spent my whole life playing rock ‘n’ roll and trying to make it, which was an impossible journey. And then suddenly you’re there! I just had this need-this desire-to learn about myself and what was going on in the world. I didn’t feel like I knew very much.

And we were very successful at that moment, and that allowed me the luxury to think. And I became obsessed with politics. It was like an enlightenment. Everything we do is political. If you’re marching in a demonstration, that’s obviously a political act. If you stay home, that’s also a political act because you’re endorsing the status quo. And that kind of thinking was like a revelation to me, and so I started looking into U.S. foreign policy, and was shocked at what I found. I felt I needed to talk about the fact that we were not supporting democracy all over the world like we said we were. We were, in fact, supporting a lot of bad people, and these bad people are like vampires that can only live in the dark. I wanted to bring that into the light and let people know what was going on, because that was the only way to stop them.

Your passion for getting to the bottom of some of these issues took you to dangerous, strife-ridden places, such as South Africa, Nicaragua, and Central America. That must have been pretty intense.

Yeah, it was. [But] I was literally obsessed. I was on a mission. I didn’t care if I lived or died. I was just totally into seeking the truth. I felt it was my patriotic duty to do something, because I love America. I love the ideals we were created around. But we haven’t lived up to those ideals, and we haven’t fulfilled the promise of America yet. It was that kind of thinking that got me going. The eighties happened to be an interesting period, because there was a lot going on. I had a list of 15 or 16 countries that the United States was actively involved in — and on the wrong side. There were another 30 or 40 issues in which we were marginally involved on the wrong side. Plus there were 45 wars going on — from Haiti to the Philippines to Morocco to South Africa and all through Central America and South America. And we were usually on the wrong side of the struggle. So there was a lot to discover. And a lot to talk about.

What’s your take on today’s music?

I personally think the pop music of the sixties was extraordinary and shall never be matched. But since the sixties, pop music for me has pretty much lost its artistic and emotional significance. It’s pretty much become wallpaper and background music and stuff that’s rather thin and temporary-something for teenagers to enjoy for a year or two and then move on to the next group. The balance between what was pop and what was rock has now shifted radically, and rock music in general is under siege. It’s actually being eliminated, and to me that’s very serious. I don’t have any problem with pop music. But when it’s almost exclusively pop music, I think we’re way out of balance. Rock music was-and is-an art form. And we don’t have that many art forms, so to have one stolen from us-which is what’s happening-is a very serious issue.

I recently spent a couple of weeks in Europe, where there’s not one rock [radio] station left. None. It’s all pop. You can’t hear the Rolling Stones. You can’t hear the Beatles. Forget about anything new. It doesn’t exist. And yet there are millions of rock fans over there, as we know. Very strange. Very strange. Here it’s not that bad, but it’s not that great, either, [especially] since the deejays lost the freedom to play what they wanted to play and. to talk about the records and supply what I call “the educational component.” All of the great deejays, like Scott Muni, have either been unceremoniously retired or they quit because they didn’t want to be handed [a list of] what ten songs they were going to play. It’s a terrible thing, because I love radio and I miss it-miss it in that sense.

What’s your songwriting process like?

I knew I wanted to make political records, and I knew they were going to be conceptual. So I outlined the themes for all five: the individual, the family, the state, economics, and religion. I would then find the album title that would best reflect the theme of the record. Then I’d come up with the individual song titles. Next, I’d divide the album into sub-themes — some general and some specific. Then I’d write the choruses of the songs, and then flesh out the rest of the lyrics. I would usually write the songs in order as they appear on the record. And I’d usually write on the road while I was on tour.

How did you get your part in The Sopranos?

It’s an odd story [laughs heartily and lights up a cigarette]. One of my best friends is a guy named Frank Barsalona. He’s a legendary figure in rock ‘n’ roll and was the first guy to start a purely rock-’n’-roll agency. He represented almost everybody. He booked the Beatles, and today he’s Bruce’s agent. He’s also on the board of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. So every year he’d come back from the Hall of Fame [induction] meeting and I’d ask, “Did the Rascals get in?” And every year he’d say, “No. They don’t wanna let the Rascals in.” Finally, about five years ago I said, “Frankie, don’t come back from one more meeting and tell me the Rascals aren’t getting in, because this is ridiculous, and if there’s a problem, I want you to arrange a special meeting of the board, and I wanna come in and state the case for the Rascals.” Anyway, he made the case for the Rascals and they finally got in. So then he says to me, “Why don’t you induct them?” And I said, “No way. Are you kidding? That’s a fucking insult. I’m nobody here. They’re one of the greatest groups ever. Get somebody famous.” So months go by and I kept saying no, but finally-although reluctantly — I said okay. I decided to do this little three or four minute comedy monologue, bringing them in.

Meanwhile, in California, David Chase is creating a new TV show, and he wants New Jersey to be part of its identity and he’s looking for new faces. He wanted fairly unfamiliar actors to be in it. Anyway, the night of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, which was being televised for the first time, he’s clicking around with his remote and he sees a photo montage of the Rascals and says, “Oh, the Rascals.” He happens to be from New Jersey and happens to be a huge Rascals fan. He also knew of the E Street Band and even knew my solo works, and then on I come and do my thing, and he says, “I want him for the show.” So he tells Georgianne Walken, the casting person for The Sopranos, to find me, which wasn’t easy to do. I had no record company, no publicist, and no agent. I had no connection to the entertainment world whatsoever.

Anyway, she finds me through the corporate pages of the Solidarity Foundation, and a friend of mine named Doc, who runs Solidarity along with another friend named Alex, calls me up and says, “Somebody called and wants you to be on a TV show.” And I said, “Yeah, right.” [Laughs] Just what I wanna do, you know? I said, “Tell them to send a script.” So I forgot about it. But then Doc calls the next day. Oddly enough, he read the script, which is a very strange thing to have happened because he’s extremely busy. [Laughs hysterically] He and Alex have been working on an encyclopedia on Native Americans, so they’re busy all the time. So he says, “This is really good. You gotta read it! You gotta read it!” So he kept on bugging me, and I said, “All right, I’ll read it.” And it was good, obviously.

But you start to wonder about destiny. You really do. I happened to get the Rascals into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I happened to induct them. It happened to be the first time it was televised. David Chase happened to be clicking around. He happened to be a fan of the Rascals. He happened to be doing a show about New Jersey. I was like, “Whoa!”

Was it difficult to make the transition to being an actor?

You basically have two or three things going on here. First of all, there’s the craft itself, which is obviously something I had to just jump in and learn as I went. But, for whatever reason, I felt I could transform myself into this other guy. I was a fan of the genre and I had a picture of who this guy was. The learning process, of course, is just beginning and will go on forever.

But the actual acting process took some getting used to. I’m used to the artistic process being a little more in my own control. For example, when you make a record, you walk into a room, sing a song, come back in the booth, and listen to it. If you want to make some changes, you go back in and make them. With the acting process, you walk into a room, you act, and then you see it six months later [laughs]. You’re totally dependent on the director, and, to some extent, on the other actors. “How’d I do?” you know. “How was I?” But it was an uncomfortable feeling, because I thought to myself, “Well, this is a director’s medium, but how do they know what I can do?” You know what I mean? How do they know if it’s the best I can be? They can’t know that. All they can know is if it’s what they need. If it works for them, it’s gotta work for you. So I had to let go of that whole control thing.

Why has The Sopranos been so successful?

I think people relate to the situations and the general premise of the show, which is, everybody has two families — your family at work and your family at home — and nobody has enough time these days for either one. You have problems in both families that run into each other. The problems at work sometimes are carried home, and vice versa. And I think everybody goes through that sort of juggling act.

Of course, it’s made a little more dramatic by [Tony Soprano’s] type of work, but if it was just a mob show, I don’t think it would be as successful. I certainly think the whole mob thing is a standard American genre now, so there’s that familiarity, which creates a nice comfortable context for people to kind of know the world. We’re able to take that familiarity and show you a bunch of stuff that you weren’t familiar with, without necessarily having to explain the basics. And you know the basics. [Laughs] These guys do some bookmaking; they do some of this, they do some of that. You already know that stuff. Now let’s show you their emotional conflicts. Let’s show you their thoughts. Let’s show you their personal problems and their home lives. It’s familiar and detailed and relatable in the broad sense because it reflects something in everybody’s life.

Do you like the characters in The Sopranos? Is there something heroic about them?

No. There’s nothing heroic about them. I think we go to great pains and great effort [on The Sopranos] to not romanticize these people. I think if you’re watching the show and you want to join the Mafia, you need a psychiatrist [laughs]. It’s nothing but trouble. Tony Soprano has nothing but problems. At work. At home. You name it. So I don’t think they’re particularly heroic. I think they’re very, very normal in their own way. They just happened to grow up in that gangster environment, and, for them, getting into that line of work is as normal as a cop’s son becoming a cop. It probably wasn’t even so much a career choice for them, either. It was just inevitable. I think the moral issues that arise from their work are often talked about in the show, which is great, because there are plenty of moral choices — even in the context of that particular world. I think one of the points of the show, too, is that this world is not as isolated as it used to be. I think in the old days it was more of an alien, isolated island within society. It’s not so much like that now, and I think we show that, for example, through interaction — like at their kids’ soccer games. It’s like the line between straight society and the gangster society is a bit more blurred now.

Do you see any similarities between Silvio and Little Steven?

There’s only one thing I can think of: Neither of us relates particularly well to modern culture. We live in different eras. I remain in the sixties, and he’s probably more in the forties or fifties. Maybe even the thirties. But we both tend to be throwbacks — people who live very much in the past in terms of things we like and things we relate to. He’s probably a little more nostalgic than I am. I think he, as well as Tony Soprano, feel they really did miss the good old days, to some extent.

I’ve experienced that a little bit less, although certainly in 1972 I felt very much that I had missed the renaissance of the sixties, which I did, even though I was there. But I certainly didn’t participate in it and I quit playing at that point. I just said, “It’s done. It’s over. Everything great has been done.” I wasn’t that far off [laughs]. I don’t know if I’d want it to be the sixties again. I don’t have a particularly romantic vision of it all. I think it was the most significant decade maybe ever. One of them, certainly. But I don’t have any great need to go back and relive it. I’m living the parts of it that I want to live now, whereas Silvio and Tony and those guys are probably a little more nostalgic.

Do you like acting?

I like acting on this show. I like this character. I understand him. I love these writers. I love these producers. I love working with HBO. And I love the working environment that we’ve created with this group of actors.

How do you balance all your commitments?

It’s not too bad. Last year was a little tricky because we did the [Springsteen] tour and the second season of The Sopranos simultaneously. So I had to fly back every day off, and the Sopranos production people were kind enough to schedule my scenes on days off from the tour, which was great. This year, the tour ends before the third season begins, so that’s not a problem.

What’s suffering a little bit is my very important hobby [laughs], which is my work. Born Again Savage is the first album I’ve ever put out without a tour. And I’m limited in my ability to even promote it, plus I’m also limited by the fact that it’s on my own label, Renegade Nation. It’s extremely difficult for a little independent label to succeed these days. But at least I got it out, and I’m very proud of it. In the meantime, my two jobs come first. I love both of them.

How does it feel to be back on the road with Bruce and the band?

It’s great. It’s a wonderful thing and really an honor to play with this band. I think we’re one of the best bands in history. And it’s more fun than ever now that we have not only the original band but also the two people that replaced me when I left — Nils Lofgren and Patti Scialfa. That just makes it even better. We have a unique interaction with each other and a unique sound and these great, great songs. And equally enjoyable is reconnecting with this audience, which is the most loyal in the world. But I think we’re out there doing something that’s actually important, you know? We made sure, as much as we could, that the shows would be very much in the present tense. In an era in which there’s this shortening attention span and nobody has time for anything because they’re running around, we stop time for three hours a night. We communicate community; for three hours, each arena is a community.

Is there a chance of a new Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band studio album?

I certainly think there’s a good chance of that. I don’t know when. We haven’t really talked about it, but one has to assume that it’s an inevitable step in this permanent reunion, which I think it is. So I think sometime in the next year or two, that’ll probably happen.

It sounds like you’re on a roll with all of your pursuits. What keeps you going?

I’ve never stopped loving music. When I was growing up, music was not only enjoyable, it was essential. Rock ‘n’ roll is my religion, essentially. And I think there’s a war going on to exterminate it. So there’s a lot to do right now in terms of making sure that this important art form survives. I’m still passionate about it, as you can hear in my latest album. And if you’ve seen us onstage, I haven’t changed one bit since I was 15 years old. I walk onstage, planning on doing the best show anyone’s ever seen — every night. I walk into a recording studio, planning on making the best record anyone’s ever heard — [laughs] certainly the best I’m capable of. And now — much to my surprise — I’ve found a new thing to be excited about with this acting thing. And I’m not sure where it will go — if anywhere. But I’m absolutely passionate about acting in The Sopranos. It’s a fantastic new experience, and participating in a whole new art form is nothing but fun. As long as The Sopranos lasts, man, I’m gonna love every minute of it.