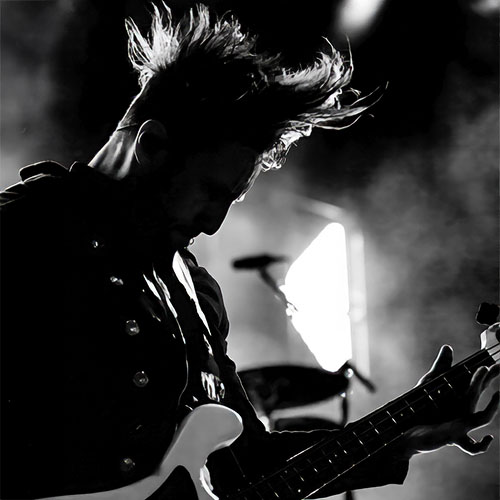

Buzz: It’s the elusive whir that makes the rock world run, and the Strokes have it in abundance. Distinct from its all too common cousin hype, it’s an electric noise that can’t be manufactured, a sort of unspoken consensus that here is a band that matters.

Different Strokes

Impossibly cool and unrealistically handsome in their black leather, their seventies shag haircuts, and their Mediterranean complexions, the five New York City twentysomethings tear through their set with sweaty exuberance as a capacity crowd of journalists, radio insiders, and record-company weasels are swept up by the energy of the snarling melodies and breakneck rhythms.

The Strokes are living up to the promise of The Modern Age, the debut EP they released on England’s Rough Trade Records, and they know it. But the fact that they’ve got almost all of this jaded crowd pogo-ing in place isn’t quite enough to satisfy them. They want to convince everyone. Singer Julian Casablancas can see the disinterested middle-aged executive standing in the center of the throng. This guy has places to go, other acts to see, an expense account to abuse, and a ponytail to flaunt. When he impatiently looks at his Rolex and scans the evening’s schedule for the third or fourth time, Casablancas finally lets him have it. “Don’t you fucking look at your watch while I’m singing!” the front man shouts, then returns to the tune without missing a beat. Behind him, the band doubles the intensity of its attack, and Mr. Ponytail quietly slithers from the room.

To find the last New York band that generated any real national excitement, you have to go back to the early eighties and avantgarde noise rockers Sonic Youth or frat-party rappers the Beastie Boys. Part of the problem is the intense media pressure cooker that is New York — it’s hard for an artist to develop something original under the glare of a million spotlights. There are also the harsh realities of real estate. It’s hard to be a garage band in a city where renting a parking space can cost $1,400 a month.

The Strokes entered this rat race with a distinct advantage. All but one of the five are children of privilege, the offspring of immigrants who came to New York from Europe or South America and scored big. Julian’s dad is even famous: John Casablancas is the founder of a chain of modeling schools and the former head of one of the city’s most successful modeling agencies. Father and son aren’t especially close; Julian was raised by his mother under a different roof, and he denies rumors that he did some modeling for his dad. But the elder Casablancas did pay for the part of his son’s music-school tuition that a two-year scholarship didn’t cover.

Casablancas, Nick Valensi, and Fabrizio Moretti met and became fast friends during their high school years, in the mid-nineties, bonding through a common obsession with music. Unlike most of their classmates, whom they describe as a bunch of “wannabe homies” and soon-to-be Eminem fans, they were never drawn to gangsta rap. Instead, they listened to the then-current alternative bands — Nirvana and Pearl Jam — as well as to the sounds passed down by parents and older siblings, everything from seventies punk to Bob Marley. This, coupled with a natural rebelliousness, set them apart from the “in” crowd, and it drew them closer together.

“I don’t know if we were the outsiders, but there was definitely a group of popular kids, and it wasn’t us,” Valensi says. “We were just into playing music.”

“Overall, it was a pretty bad experience for all of us,” Moretti says of their shared high school. “Eventually Julian quit, and Nick left around tenth or eleventh grade. I was left there by myself, and it was horrendous. We were really the only friends each other had.”

“You’ve got people stacked all on top of each other here, so there’s gonna be that little taste of New York in the music… a vibe that comes across.”

The trio learned to play their instruments together, with Valensi devoting himself to the guitar that he first picked up at age five and Moretti mastering the drums by practicing in a soundproofed closet in his mother’s apartment. Eventually they were joined by bassist Nikolai Fraiture, a friend of Julian’s from grammar school, and Los Angeles-born second guitarist Albert Hammond Jr., whom Casablancas met at 13 during a short stint at a Swiss boarding school. (Julian’s dad sent him there thinking it would straighten him out, but it only intensified the kid’s desire to rock.)

From the beginning, Casablancas was the band’s leader and songwriter, chronicling typical post-adolescent romantic woes (“It hurts to say, but I want you to stay”), griping about New York City cops (“They ain’t too smart”), and pondering life’s big questions (“Is this it?”). He did it in classic rock fashion — with maximum energy and undeniably strong hooks.

“Julian was writing cool songs before he even knew what he was doing, when he only knew how to play on one string,” Valensi says. “He’s able to take some influences, listen to something, take what’s good from it, and leave behind what’s bad. He can listen to the Beach Boys and leave behind the pussy, wimpy stuff and only take these cool chord progressions or unheard-of melodies. He can listen to Freddy King and take all the balls and aggression that you get from it but leave behind the standard blues progressions.”

On “Barely Legal,” “Someday,” and the title track from their just-released debut album, Is This It (RCA), the Strokes also incorporate unmistakable echoes of New York rock history. There are hints of the serpentine guitars of both Television and Richard Hell and the Voidoids (Valensi and Hammond rarely play separate rhythm and lead parts), of the spirited, pogo-worthy rhythms of the punk and new-wave bands, and of the glamorous, sexy swagger of the New York Dolls. But mostly there are the insistent pulse, droning riffs, subway-train rhythms, and urgent, monotone vocals of the legendary group that preceded and inspired all of the above.

“When I was probably 13 or 14 my brother bought me a Velvet Underground CD, and I just loved it,” Casablancas says, somewhat sheepishly. Valensi adds, “The VU was hugely inspirational. It’s the one band that all five of us can unanimously say, ‘They were a great fucking band!’”

Critics have long scoffed at the notion of authenticity in rock: This is a music born of blatant thievery; everybody steals from everybody else, and if you’re gonna rip somebody off, you might as well turn to the best. So better the Strokes take a page from the Lou Reed songbook than be another in the long line of rap-rock clones. Still, until recently, Casablancas was reluctant to admit the level of his Velvets fandom, for fear that it would somehow cheapen the accomplishments of his own songwriting. And all the band members think “the whole seventies New York rock thing” has been overemphasized by the press in stories about the Strokes.

“I gotta tell ya, to be compared to the Velvet Underground and the Stooges and stuff like that is such an honor that I can’t complain,” Moretti says. “But if you listen to the album, the influences are very wide, and there’s a lot of different influences. I can’t say that it’s always justified, the comparisons. I think it’s just that when you come from the city, there’s a certain vibe that comes across in your music. It’s not necessarily in the notes that you play and the lyrics that you sing; it’s just a little bit of the energy. You’ve got a bunch of people stacked all on top of each other here, so there’s gonna be that little taste of New York in the music.”

“It wasn’t like we sat down and said, ‘Let’s shoot for this,’” Hammond adds. “It was the opposite — like, ‘Gimmicks don’t last. They’re great to boost you up fast, but then they go away.’ Pretty much it was just Julian trying to write good melodies, but with balls, and it just so happens that those songs remind people of the seventies. Stuff like Limp Bizkit and Korn — that’s not balls to me. That’s fake, like putting steroids in your body.”

Fake versus genuine — it’s an issue that plagues the Strokes in some corners of the New York rock scene, where other bands that are clearly jealous of this group’s rapid ascent can be heard mumbling about “spoiled rich kids” and the sort of unbelievably lucky breaks that just don’t happen for “the rest of us.” Ressentiment, Nietzsche called it — a spirit of revenge that festers in the weak, prompting them to seek vengeance against the strong, the noble, and the talented. As if Fred Durst is somehow more worthy of success than Julian Casablancas; as if much of the best music throughout rock history hasn’t been made by upper-middle-class art-school students like Pete Townshend, John Lennon, and Joe Strummer.

“Being on the road is like a vacation: You get to see different towns, and you play shows. But recording was painful; it sucked out my soul.”

In reality, the Strokes’ “overnight success” was at least three years in the making. It’s understandable why the five band members are a little defensive when stressing just how hard they’ve worked: They spent countless all-nighters honing their material in a cramped and smelly rehearsal space in midtown Manhattan’s Music Building (rent: $300 a month), emerging with red eyes, squinting in the morning sun, as they stumbled to dead-end day jobs that they were only recently able to quit.

The group had been gigging regularly all over the city for a year and a half when it got its first real break, winning an influential fan in Ryan Gentles, then the booker at the hipster haven Mercury Lounge. “I’d get a lot of the same kind of shit in there day and day out,” Gentles says. “I was a musician, and I got that job because I wanted to help bands, but very few came along that you actually wanted to help. When I got the Strokes demo, I was just so floored — out of all the submissions that came in, 20 or 30 a day, nothing ever stuck out like that. I actually took their tape home with me and played it over and over again for weeks.”

Gentles, who’s only two or three years older than the guys in the Strokes, eventually quit his job to manage the band full-time. “Initially, I was just like, ‘Do you guys need some help?’” Gentles says. “And as it escalated, my phone started to ring more for them than for booking the Mercury Lounge. If I hadn’t quit, I would have been fired. Now I know I say this as a manager, but this is a band with amazing songs, the right persona, the right character — everything they do is right. It’s not an accident that it works, because they work so hard at it. Julian in particular is his own worst critic. Every good piece of press he gets only makes him think, Shit, I’ve got to work harder, I’ve got to write better. He’s always trying to outdo himself.”

Before leaving the Mere, Gentles used his clout to land the Strokes some high-profile gigs, including a weekly residency at the club and opening slots on national tours with Ohio’s underground heroes Guided by Voices and rising British favorites the Doves. The Strokes made the most of these openings: Wherever the guys played, they won fans among listeners, club owners, and local promoters.

The buzz was starting to build, and it could be heard as far away as London, where Geoff Travis was in the process of resurrecting his influential indie label, Rough Trade. One of Gentles’s pals at the Mercury Lounge played Travis a Strokes tape over the phone, and the label head was hooked. “After about 15 seconds, I agreed to release it,” Travis says. “What I heard in the Strokes was the same thing that all the writers and the general public are now hearing: the songwriting skills of a first-rate writer and music that is a distillation of primal rock-‘n’-roll mixed with the sophistication of today’s society — the primitive in the sophisticated, to paraphrase Jean Renoir. It also has an unmacho quality that embodies grace and love, and it touches me. I just felt it was the best record from a rock-‘n’-roll band out of New York City that I had heard since the CBGB’s era.”

Travis wasn’t the only Brit to fall for the Strokes. In support of The Modern Age EP, the group played two sold-out tours of the U.K. The English music press tried to outdo itself with superlatives, and the Strokes landed on the cover of the weekly New Musical Express. “They like white boys who play rock-‘n’-roll over there,” Casablancas says dismissively by way of explanation. But by the time the music industry’s largest annual gathering, the South by Southwest Music and Media Conference in Austin, rolled around this past March, even the notoriously clueless American major labels were taking notice. After entertaining several offers, the Strokes finally signed with RCA in the late spring because it was the one company that didn’t balk when the band said it would never make a video.

“The idea of lip-synching to songs on a film just seems retarded to me,” Casablancas says, though he adds that the Strokes wouldn’t mind playing live in front of the TV cameras-on, say, Saturday Night Live: “The whole Ed Sullivan thing is really cool.”

The Strokes guys are charmingly naive and old-fashioned in more significant ways than their fondness for Bay City Rollers haircuts and vintage 1975 guitar tones. The power of the group stems from the live interaction of five friends who know and love one another and who communicate best through loud music. Turn it up, drown out the rest of the world, and find catharsis through thrash — it’s a formula as old as rock-‘n’-roll itself. When it came time to record Is This It, the challenge was to capture the power and immediacy of this approach for digital posterity.

“It was like a nightmare,” Casablancas says. “I mean, I’ve seen interviews with musicians where they say that touring is hard. For me, personally, being on the road is like a vacation: You get to see different towns, and on top of it you get to play shows. It’s like a dream come true. But recording was painful; it sucked out my soul. We only had a short period of time, and it was concentrating for ten hours every day for a month and a half until 5 or 6 A.M., trying to focus on tones. I’ve never been so mentally fatigued as when I was finished with that album.”

The band eventually hit its groove by alternating recording sessions with another club residency, this one in Philadelphia. Whatever the angst that went into the creation of the album, the end result is a wonderfully raw and organic statement that virtually explodes from the speakers. Is This It is indeed one of the best rock records out of New York in a decade; hell, in these pop-and rap-rock-dominated times, it’s one of the best rock records, period. But whether it will move units and connect with the Total Request Live masses is anybody’s guess. Gentles, Travis, and the rest of the Strokes support team cringe at the mere mention of other hyped New York bands like Jonathan Fire*Eater, which debuted amid a flurry of empty major-label hype and corporate bucks before being quickly and justifiably forgotten.

To their credit, the five Strokes remain blissfully unconcerned about questions of business, just as they’ve mostly managed to ignore the distractions of buzz. “The art and the business side are very confused — they’re perceived to be the same thing, which they’re not,” Casablancas says. “I really don’t worry about where we fit in the business. I think we’re somewhere in the middle — somewhere between hardcore and the cheesy, commercial, melodic stuff. And that’s somewhere I want to be — I think all the really good artists were like halfway between commercial and intellectual.”

He pauses and laughs. “But you know,” he says, “I really don’t like talkin’ about this stuff. I’d really rather sit down with you and have a beer.”