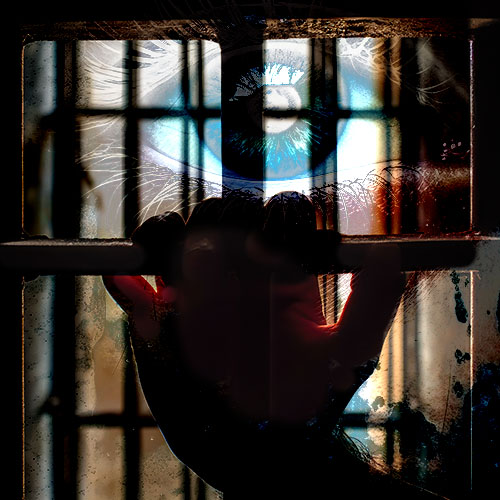

George Orwell’s novel “1984” — about a totalitarian security state — seems to have become a wish book for lawmakers.

Here’s Looking at You: Surveillance ‘R’ Us

America is under attack, and our enemies are real. But in the name of security, we have all become victims of a surveillance, tracking, and data-collection infrastructure that — indiscriminately spies on everyone, grows ever more invasive, is accessible to individuals and organizations on scant legal basis and is answerable to no coherent national legislative oversight policy.

The leadership in post-9/11 America appears bent on turning U.S. citizens into a talent pool for future Cops episodes. Amid the aftershocks of September 11 has come a push by government and commercial interests to burn camera monitoring, biometric scanning, and other surveillance technologies into the matrix of American society.

New legislation promises to relax or do away with laws restricting domestic intelligence collection, while making it more readily available to potential abusers, and emasculate already eroded constitutional protections against searches and seizures and incarceration without due process of law. New technologies can scan, track, and compile extensive databases on Americans. These digital dossiers, amassed and maintained by government agencies and multinational corporations, are becoming increasingly cross-linked and openly available to an ever-widening circle of spooks, snoops, and crooks. The implications for a society that has long cherished privacy as an article of faith are profound. If current trends continue, America could wind up dropping a digital Iron Curtain on itself, creating a surveillance state that we may not be able to dismantle even if we want to sometime down the line.

“Everyone from banks to travel agents to dotcoms selling recycles cow pies want to put your personal data on a chip and use that data to identify you, track you, and mass-market you.”

Make no mistake: America is under attack. Our enemies are real, they are dangerous, and the bastards are out there. A robust surveillance capability is critical to our national survival. Indeed, a system already exists and has existed since the establishment of the National Security Act of 1947, which led to the creation of, among other things, the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency. Congressional legislation over the years has given enhanced powers of surveillance to the FBI, CIA, and other federal, state, and local law-enforcement bodies. The NSA in particular is equipped with the most sophisticated surveillance and signals-intelligence capability on earth, but, despite portrayals in thrillers like Enemy of the State, the NSA, which is overseen by the Senate and House Intelligence Committees, has not historically targeted Americans in the United States.

It’s not surveillance per se that should concern us; rather, it’s the unbridled growth of a surveillance, tracking, and data-collection infrastructure that indiscriminatly spies on Americans, grows ever more invasive, is accessible to persons and organizations on scant legal basis, and is answerable to no coherent national legislative oversight policy. It is just such a surveillance society that seems to be slouching toward Bethlehem to be born. Should we fail to reign in the rough beast, we may all face a bleak future as drones or worse. This future might not be the sterile totalitarianism depicted in Orwell’s 1984. As John Perry Barlow, cofounder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, pointed out to me, it might also resemble the hedonistic society portrayed in Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World. As Huxley wrote in his introduction, “A really efficient totalitarian state would be one in which the all-powerful executive of political bosses and their army of managers control a population of slaves who do not have to be coerced, because they love their servitude.” Either way, a drone is a drone is a drone.

History warns that where the tools and instruments for a police state exist, that police state exists in embryo. While it may be true that the growing array of legal and technical surveillance initiatives is aimed at terrorists, none of us can be sure which way the literal or figurative gun barrel will point tomorrow. To be under surveillance is to be under control, and a nation where everybody is watching everybody else has set foot on the road to Calvary, not Woodstock. It is just such a convergence of factors, driven by self-interest and hysteria, that has led at other times and other places to the institution of police states.

Technologies for monitoring, tracking, and data collection are maturing at a rapid pace. Surveillance cameras — many linked to biometric scanning systems that match faces, body movements, fingerprints, or retinal patterns against extensive databases, and camouflaged to be hard or impossible to spot — are cropping up everywhere. Since September 11, tens of thousands of cameras have been placed around the nation’s capital. Other cities across the country, including New York, are following suit.

New cellular phones are required by law to enable authorities to trace their location. The FBl’s so-called Magic Lantern and the Department of Defense’s Carnivore technologies are primed to spy on the Internet with Zeus-like omnipresence, while many in the government advocate using supercomputers and massive cross-linked databases to ferret out and collect data on American citizens from all available sources, including telephone conversations and credit-card transactions.

In the planning stages are new driver licenses that contain extensive biometric data on the lives and habits of their bearers, and automotive versions of cockpit flight recorders for that little nook behind your car’s glove compartment. The licenses would serve as de-facto national identity cards that, in time, could be required in conducting even the most basic transactions, such as starting your car or entering your apartment building. (A federally subsidized housing complex, Manhattan Plaza, has recently become the first residential building in New York City to propose a fingerprint-scanning entry system, requiring fingerprinting of the residents of the complex’s approximately 1,700 apartments.)

With the introduction of Applied Digital Solutions’ Veri-Chip — a subcutaneous microchip implant programmed with data about the implantee — a onetime paranoid delusion of mark-of-the-beast religious fanatics is fact. There’s also Hypersonic Sound, an innovation soon to appear at a coin-op soda machine near you (it’s already in Tokyo) that can beam audio messages directly into your brain. Face-recognition technologies might, in the not-too-distant future, be a regular part of your shopping experience, right down to a publicly accessible record of your having bought the latest issue of Penthouse along with images of the pages you browsed on the way over to the checkout. This would all be kept on permanent record for use by state and commercial information seekers — perhaps even your next prospective employer.

Still more exotic technologies and fiendish devices are on the way. Time Domain, a Huntsville, Alabama-based company, has developed RadarVision, a spy scope that outdoes even the man of steel’s fabled X-ray eyes. RV sends out millions of ultra-wideband pulses per second that can penetrate concrete, dry wall, brick, wood, plastic, tile, and fiberglass, and produce on its monitor images of what’s behind any such barrier. Development of this kind of technology is high on the Defense Department’s counterterrorism wish list. Contractors with promising applications have no problems getting funded. RadarVision is currently sensitive enough to detect even the faint motions of a person standing still behind a wall. By the time you read this, it will have been improved, with even greater range and sensitivity. (Note to Miss Lane: Better foil-line your bra.)

The venerable surveillance camera may soon become a relic. So-called spy dust made up of submicroscopic cameras created through nanotechnology could be borne on the wind like ragweed pollen to transmit your every move back to central control. HAARP (High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program) technology, which can potentially create virtual “lenses” of ionized radiation in otherwise empty space, could enable completely cameraless remote surveillance. A pill camera has been developed that can photograph the interior of the body and transmit images to a monitor; could certain parts of the Penthouse reader’s anatomy one day become a secret camera or microphone for you-know-who?

Even scarier is something called “evoked-response potentials,” which means the ability to detect and assimilate the faint electrical signals generated by the human brain. Ten years ago, when I first encountered the Strange-lovian term at a military-technology symposium, you could think Yes, No, or See Spot run, and those words would appear on a computer screen. Who knows what’s possible today — or what will be tomorrow.

The key to efficient monitoring systems is biometrics. It’s a term that will become increasingly familiar as credit-card issuers, motor-vehicle departments, insurance companies, even your supermarket and landlord make these systems a part of everyday affairs. Bio-metrics refers to any technology that enables the identification of living organisms by machines capable of recognizing specific aspects of behavior, appearance, sounds, or physical characteristics. Fingerprints, voice prints, face prints, retinal patterns, handwriting, hand geometry, body language, even electrical impulses generated by the brain can be identified.

Biometrics is important to surveillance because it can sort through an information glut generated by devices that routinely record massive amounts of data. Another benefit of biometrics is specificity. “Biometric data, such as the minutiae on a fingerprint or face print, can’t easily be cloned,” says Cameron Queeno, vice president of marketing for the California-based Viisage Corporation. Unlike PIN numbers, access codes, or a set of keys, they’re unique to the individual. “There’s only one technology that can tie a person to a credential [and] to the data behind the credential; that’s biometrics.”

Industry experts promote the benefits of biometrics-enabled surveillance technologies. Queeno mentioned a multi-million-dollar credit-card identity-theft scam that was in the news the day we spoke. Had proper biometric safe-guards been in place, it would have been much harder or even impossible to bring off. So far, though, real-world tests of biometric systems have produced mixed results. As one (but not the only) example of a snafu, ldentix Corporation’s Facelt face-recognition software engine — which scans facial features, breaks them down into binary code, then matches them against a photographic database — had an approximate 50 percent success rate during a month-long trial at Tampa International Airport under optimum conditions. (The company cites a 90 percent success rate in other trials, though test data are not yet publicly available.)

And what about the risks and drawbacks? Electronic Frontier Foundation’s John Barlow, who believes we’re “sleep-walking toward a police state,” ponders the dangers posed by automated systems: “What they’re talking about is creating large systems that don’t have human judgment. What will happen when machines will be watching and making decisions that could be life-threatening if the machines make a mistake?” Open the pod-bay doors, HAL.

The risk of a sprawling system of supercomputers that has the goods on everybody should be obvious. The end users of equipment that scans, tracks, records, and analyzes people’s movements have traditionally been government agencies, municipal facilities like airports, and big corporations. In the past, use of this technology was highly restricted, but that is changing fast. Lay your money down, and anyone can play. At this writing, everyone — from your bank to your travel agent to the dotcom s that want to sell you recycled cow pies — is lining up with plans to put your personal data on a chip and use that data to identify you, track you, and mass-market you. The government might claim with some justification that such efforts help fight terrorism, but what about the greedy schmuck trying to sell you the latest widget?

The questionable motives of many of these info parvenus raise obvious legal, ethical, and moral questions. Laws governing the use of data tracking have always been fuzzy or nonexistent. Well before the push after 9/11 to loosen the reigns on surveillance, data collection, and data sharing, the gray areas have led to numerous abuses. Information brokering, a multimillion-dollar business, enables companies to gather information on U.S. citizens with startling ease. The crime of identity theft has come into existence largely because of the vast amount of accessible information within the grasp of those with little or no right to possess it. While some have employed identity theft as yet another justification for increased monitoring of Americans, the fact is that without the extensive pool of free-floating data, ID-theft scams would not be possible; increased data collection might very well worsen the problem.

“For many governmental and commercial entities, the events of 9/11 marked the chance to put covert agendas into action.”

Fuzzy or missing to begin with, the legal constraints that have prevented even more questionable domestic surveillance may be eroded or rescinded under the USA Patriot Act, which incidentally stands for “Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism.” Under Patriot Act provisions, Internet service providers may legally furnish “noncontent” information (such as the TO/FROM and SUBJECT lines of e-mail) to law enforcement. Other Patriot statutes give the government access to content of online chat-room sessions, search-engine keywords, GPS navigation-system data, and transactions made via e-mail, credit card, or ATM — basically, anything with a magnetic data strip — all without court approval.

USA Patriot’s so-called sneak-and-peek provisions allow investigators to covertly enter Americans’ homes in search of incriminating evidence with only a “simple warrant” that does not require a court order, while other statutes, including “domestic terrorism” provisions, could potentially make it easy for prosecutors to build cases against suspects based on evidence that would not previously have been admissible in court. Could your thoughts, amplified by a chip implanted in your skull, someday be available for reception by an evoked-response-potentials scanner and used as evidence against you?

For the present, it’s the multiplication of security cameras in public places that’s the most visible sign that we are being watched. England’s Orwellian experiments with closed-circuit-TV monitoring of its citizens have sparked comparisons to Big Brother and led to privacy hawks charging that the United Kingdom, with an estimated 1.5 million public cameras, is now a de-facto police state. In the United States, Washington, D.C., is ringed with more than 20,000 surveillance cams, with the number set to increase dramatically by this time next year.

If trends continue, the future surveillance-camera capital of the U.S.A. might turn out to be New York City, rivaling or exceeding even London in the number of surveillance cams per capita. While the cameras watching them have multiplied like rabbits, denizens of America’s largest city are blissfully ignorant of the lenses tracking them, the antennas broadcasting their personal data, and the computer banks keeping records of both.

One cold, rainy Sunday afternoon last November, I took a tour of those Big Apple surveillance cameras. The locale was the grid of streets bordered by Grand Central Station to the west and the United Nations to the east, from 42nd to 52nd Street. The area is home to consulates and embassies, shops, apartment buildings, parks, bars, a landmark church, and a homeless shelter — as perfect a microcosm of urban life as you’re likely to find.

Groups of camera watchers have sprung up in cities around the world. The New York Civil Liberties Union’s Surveillance Camera Project and the Surveillance Camera Players both give camera-observation walking tours of the city. The SCP’s version is called Surveillance Camera Outdoor Walking Tour. To gather information for this article, I went on a SCOWT, but also returned twice to scope spycams on my own.

Bill, the tour guide for my SCOWT, said he started giving tours after the United Kingdom, with the most surveillance cameras in the world (approximately one camera for every 50 people) signed the Data Protection Act. As for the number of surveillance cams in Gotham, either nobody’s keeping records or the stats aren’t being made public. My own research indicates there are anywhere between 3,000 and 6,000 cameras in Manhattan alone, roughly 300 cameras for every neighborhood district in the borough. According to SCP’s estimates, in the past four years the number of cameras in New York’s Times Square has tripled. SCP estimates that in three years there will be at least 10,000 surveillance cameras at street level in Manhattan, approximately one for every street corner.

Bill tells us our tour group is already under suspicion. We’re lingering conspicuously; we’re also standing in a circle, an uncommon pattern amid the lines and squares of daily activity. Computers connected to the cameras can be programmed to detect such irregularities and begin recording. Bill says they’re doing this right now. Monitoring us. Tracking us. Recording us. Creating a record of our presence. Hearing this, three people leave our group.

Where are these cameras? They’re all around us. Across the street two surveillance pods are visible high atop the Israeli embassy building. This isn’t surprising. But there are also cams atop city lampposts. On the southwest corner of 42nd and Second Avenue, a snow-white gooseneck pod stares down at everything below. Behind its translucent black glass, presumably, are day/night cameras that can tilt, pan, and zoom, as sensitive in darkness as they are at noon. Like other public surveillance cams, they don’t look like cameras; they are part of the lighting stanchion itself, placed high overhead where New Yorkers are not normally expected to look.

The cams are operated by the NYPD, whose intelligence division also uses mobile units. These units conduct surveillance from the air using helicopter-mounted cameras and infrared sensor pods, and on the ground from vehicles disguised as delivery vans, taxis, and the like. A repeal of the 1985 Handschu Agreement, a federal court order that imposed restrictions on the NYPD’s monitoring of noncriminal political activities, would broaden NYPD surveillance powers. (In February a Manhattan federal judge loosened Handschu at the behest of law enforcement.) The cameras have been installed in areas considered prone to terrorism or crime — and there are many crimes on the books here, jostling and jaywalking to name but two.

Across 42nd Street, the traffic-signal arm projecting onto the downtown lanes of Second Avenue has three stationary cameras and three strobe sensors set in two parallel rows. They flash rapidly as passing vehicles are scanned, tracked, and photographed. Flash, flash, flash, go the sensors. Click, click, click, go the cams. Up, up, up, goes the blood pressure of New York’s motorists slapped with tickets for speeding and running red lights. Many of those tickets, to judge by past examples, will have been wrongfully issued.

Typically, installers of traffic cameras cut deals with the municipality that give the companies a percentage — up to 50 percent — of resulting fines. In San Diego, where Lockheed Martin IMS installed similar traffic-surveillance cams at red-light intersections in 1998, and where Lockheed was collecting approximately half the proceeds of each ticket generated by its automated systems, it was charged that the company deliberately placed some of the cameras too close to the intersection and reduced yellow-light time. A judge threw out 292 traffic tickets issued by traffic cameras that year. An increased accident rate was also claimed for San Diego and other cities, including Los Angeles (where Lockheed also operated cameras), where it was reported that accidents were up at traffic-camera intersections and had increased as much as 11 percent citywide.

On to the corner of Manhattan’s 44th Street and Second Avenue, where a cluster of slab-like gray antenna elements is visible on a nearby rooftop. Such antenna clusters are familiar to New Yorkers, who’ve been seeing them crop up for years but generally know nothing about them. If people think of them at all, most assume that they’re for pay-TV or satellite-TV access. The units are actually microwave repeaters used for a number of purposes, including reading E-Z Pass toll-booth tags on cars and propagating cell-phone transmissions. These antenna elements are connected symbiotically to the cameras on the street and in the air. The antenna clusters pull in microwaves from all directions. They can also pick up wireless video signals. The signals used by many transmission systems are unencrypted; they can be scooped up and viewed or heard by anyone with the right technical capability, and there are plenty who have it. Hackers have used signals bouncing off digital repeater arrays to eavesdrop on everything from surveillance imaging by Global Hawk and Predator unmanned aerial vehicle sensors to nanny cams in nurseries. In the case of the UAVs, the signals are downlinked from the high-flying spy air-craft to commercial satellites for retransmission to ground receiver stations. In the near future, repeater arrays will be essential in pulling in signals from third-generation video-enabled cell phones and wireless microcams worn by street-level spies.

I turn right on 44th Street and head toward First Avenue and the United Nations. On the SCOWT, Bill had cautioned us not to take pictures here. Those who’ve tried it in the past have often been confronted by baton-brandishing security guards who’ve appeared from inside the foreign consulates that line the street; passersby may be photographed and videotaped, but it’s a one-way proposition. I pass the United States Embassy, where more cameras monitor the street from lamp-posts and the building. A block ahead is the Turkish Center. Here you can sometimes see a staffer sitting behind a desk in front of color monitors; the angle is such that you can see what’s on the screens — not surprisingly, that something is you.

On the November SCOWT, both Bill and Yevgeny, my fellow surveillance tourist, were visible on the monitors and probably recorded on videotape as well. It’s a sobering experience: Multiply your image on that screen a hundred-fold, and you approximate the number of times you might be surveilled and recorded in the course of a normal workday. Atop the front of the U. N. General Assembly building, a large surveillance cam angles down into U.N. Plaza.

Yevgeny and his companion, Nadia, who did not speak English, seemed anything but concerned; in fact they looked like they were having fun. I asked Yevgeny where he and Nadia were from. The Soviet Union, said Yevgeny, where he had been a journalist and a translator. I asked why they seemed unconcerned, even … happy. Was this a Sunday stroll for former members of the proletarian masses longing for that good-ol’-fashioned back-in-the-U.S.S.R.-style state surveillance?

Yevgeny puts the nyet on that fast. They’re on this surveillance field trip because they are now Americans. They live in a free country. If there are cameras watching them, Yevgeny and Nadia have a right to know about them. “If you’re doing nothing wrong, you shouldn’t be concerned,” Yevgeny tells me before he and Nadia leave.

Gary T. Marx, professor emeritus of sociology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, disagrees: “Some people ask, ‘What’s the big deal, as long as you’re doing the right thing?’ But in fact, we don’t set up our public policy simply in terms of pragmatism. In fact, we make it deliberately hard for law enforcement to get its job done” in a free society.

Hunched against the slanting icy rain that pelts the city, I head toward the subway. I swipe my MetroCard at a turnstile that automatically records the card number, station of entry, and (if I had paid by credit card) my identity.

At the Bleecker Street East Side IRT stop, two armored security cams stare down at the platform. There are three more cams in dull gray housings on the lower mezzanine between the IRT and IND lines. On both the uptown and downtown platforms of the tracks below, I count another three cams mounted above the platform. A bank of three color CCTV screens at the center of each platform runs live feed, showing views of the platform and adjacent tracks. Some of the screens show only static; either the cams or the monitors are on the blink.

The monitors again brought home the pros and cons of the issue. Surveillance, in the service of a coherent policy, can be useful. While corrupt companies rip off motorists with rigged speeding fines, the monitors on the Broadway-Lafayette F platform allow passengers to scope out trouble lying in wait late at night — a good thing in the city that never sleeps. But systems monitoring passengers’ MetroCard usage are another matter. The issue’s complexities are overshadowed by the catchall justification to fight terror. Many lawmakers, and the biometrics industry itself, recognize this; responsible members of both have called for a national debate and policy on surveillance.

For those who think a Democratic win in 2004 will make it all go away, think twice. Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, are divided amongst themselves on the issues. The proliferation of mass surveillance did not begin with a Republican win in 2000, nor would it end with a Democratic administration in 2004. Neither will the questions it must raise in any free society.

“There have to be some trade-offs ” in defending the nation against terrorism, says Senator Richard C. Shelby (R-Alabama), the ranking majority member of the House Intelligence Committee. “But do you trade off with basic constitutional rights? I don’t think we have to. Some people would say we’ve got to give up a lot. I think we all have to give up something for security…. But I don’t think Americans want to give up everything, because we are strong enough to prevail if we… go after and destroy the terrorists that would harm us.”

A report released in September 2002 by an independent task force sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations, chaired by former Senators Gary Hart (D-Colorado) and Warren Rudman (R-New Hampshire), echoes this assessment: “In the end, security is not just about protecting American lives. It is also about sustaining systems that support our way of life in the face of designs to exploit or target those systems…. Ultimately, the end game must be to continue to live and prosper as an open, globally engaged society, not to become a nation trapped behind the modern versions of moats and castles.”

Some critics have detected a Gestapo-like ring to the phrase homeland security. But it was not a coinage of the present Bush administration: A Clinton-era white paper issued by the Defense Department in December 1997 used the words “security for the homeland,” and proposed that “the entire U.S. national security apparatus must adapt and become more integrated, coherent, and proactive.” Issued during a period of global stability, references to needed changes in “security structures ” at home did not then have an ominous ring.

That the Big Brother of George Orwell’s visionary novel 1984 might be lurking in the shadows was not apparent to anyone in the go-go nineties, with the possible exception of members of those governmental and commercial entities with a vested interest in such a development. For them, the events of 9/11 marked the chance to put long-hidden covert agendas into action. As EFF’s Barlow told me, “On 9/11 I knew that the control freaks were going to dine out on this for the rest of their natural lives.”

It bears repeating: The issue is not about technology; it’s about control, and about the kind of society we want to live in opposed to the kind they want us to live in. Do we want a society in which we are constantly under unchecked surveillance by corporate and government entities? Do we want a society in which our fingerprints are scanned in order to boot a computer, enter a building, or buy a pair of sneakers? Do we want a society in which extensive information on us is stored perpetually and is accessible to virtually anyone? We need to ask ourselves how such pervasive monitoring would impact our lives. We also need to ask how secure these new surveillance measures would really make us.

In the end we need to strike a compromise between security and privacy, a balance that will preserve our constitutional rights while defending us from the undeniable threats of terrorism and crime. Otherwise, in the name of national security, we are in danger of defending democracy — to death. The issue of surveillance requires a national debate and national policy, lest we rush headlong into a society of suspects where everyone, all the time, is being watched, and we are all permanently under control.

Did you not find it ever-so-cute when the author suggests that solutions will only come with national policy and respectful debate. As recently as 20 years ago (as of this publishing) people still thought that approach reasonable. Weren’t they just precious? … Well, we have more surveillance than ever these days as everyone well knows, and it has become altogether too easy for those afraid of it to rage against the machine. Fair enough, it may be a problem. Or it may not. Technological advance in leaps always seems to require a sacrifice of anonymity certainly, but who’s to say whether the ends justify the means? For what it’s worth we did look around at more than a few groups like this, and not one of them seemed to have an authentic tin-foil hat embellished with a cool logo. Seems like a missed opportunity, really.