The Drummer of The Doors recalls his Strange Days with rock’s most legendary madman.

Riders on the Storm

It seems that whoever met Jim Morrison walked away with a different impression: southern gentleman, prick, poet, brute, charmer, et cetera.

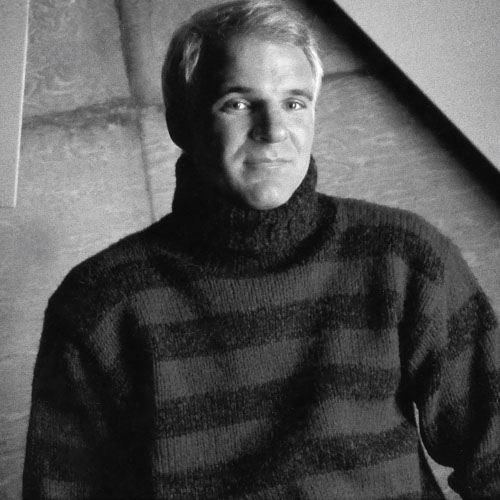

I lived with Jim for six years on the road and in the recording studio. This book is my truth. It may not be the whole truth, but it is the way I saw it. From the drum stool.

In my book Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and the Doors (Delacorte Press). I have also included some early autobiographical roots that shed light on my musical influences, and I’ve taken my story up to the nineties — a single parent, in my forties, and surviving.

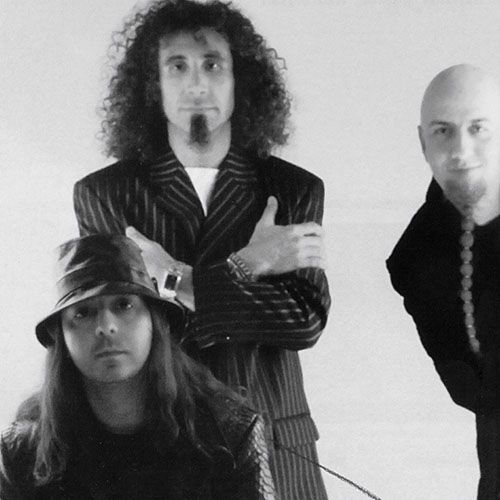

In the spring of ’65, long hair meant rebellion. Most of my college classes were not compelling, and I knew I had to take a gamble on what I was best at — playing music. And it was then that my friend Ray Manczarek (that’s how he spelled it then) happened to give me a call. He invited me down to his parents’ place in Manhattan Beach to play. I entered by the beach house just in time to hear his parents make several unkind remarks about their son living with a Japanese girl. I exited quickly and went out to the garage/rehearsal room. Out came Ray with his beach things on and a daisy in his shirt. He seemed warm and friendly. Good-natured. I liked his frameless glasses, which to me looked groovy. Intellectual-like. He introduced me to his two brothers, Rick, the guitarist, and Jim, the harmonica player. Their band was called Rick and the Ravens.

Lurking in the corner of the garage, meanwhile, was this guy wearing standard collegiate brown cords, a brown T-shirt, and bare feet. Ray introduced him as “Jim, the singer.” They had met at U.C.L.A. film school. Ray was moonlighting while pursuing his master’s degree in film, after a B.S. in economics, and Jim was finishing up a four-year degree in film. He was in an accelerated two-and-a-half-year program. Smart guy. They had played together once when Ray was stuck with a union obligation for a sixth member of the band, and he convinced Jim to stand off to the side of the stage with a guitar that wasn’t plugged in. They were backing up Sonny and Cher. It was Jim’s first paying gig, and he didn’t play or sing a note of music.

The 21-year-old Morrison was shy. He said hello to me and went back to the corner. I suspected he felt uncomfortable around musicians, since he didn’t play an instrument. While Morrison moped around the garage looking for a beer, Ray grinned like a proud older brother as he handed me a crumpled piece of paper.

“Take a look at some of Jim’s lyrics,” Ray said to me.

You know the day destroys the night

Night divides the day

Tried to run, tried to hide

Break on through to the other sideMade the scene, week to week, day

to day, hour to hour

Gate is straight, deep and wide

Break on through to the other side

“They sound very percussive.”

“I’ve got a bass line, wanna try something?” Ray said.

“Yeah, let’s do it.”

Ray began and I used a knock sound on my snare, putting the stick sideways. Jim Manczarek joined us with some funky harp playing. Morrison, after a long wait, finally started singing the first verse. He was very tentative, not looking anyone in the eyes, but he had a moody kind of sound, as if he were trying to sound surreal. I couldn’t stop looking at him. His self-consciousness drew me in. Rick was playing very soft rhythm guitar, but Ray had nice energy coming from the keyboards. Then we played a couple of Jimmy Reed songs and Morrison’s energy picked up. I agreed to come down for some more rehearsals, as I loved to play. I knew they wanted me, and I thought I’d follow this lead for a while.

The next few rehearsals went about the same, but I was getting more and more interested in the originals. We eked out the arrangements together, and I felt I was with kindred spirits, Ray especially. Ray remembers: “We’d listen to Jim chant-sing the words over and over and the sound that should go with them would slowly emerge. We were all kindred souls — acidheads who were looking for some other way to get high. We knew that if we continued the drugs we’d burn out, so we went for it in the music!”

Also, Morrison was mysterious. I dug that.

By now all we lacked was a name. At the time most American groups had long psychedelic names, like the Strawberry Alarm Clock, the Jefferson Airplane, or the Velvet Underground.

It was orange blossom time, the summer of 1965, T-shirt weather, and I was sitting in the backseat of Ray’s yellow VW bug as he headed south on the San Diego Freeway. Jim was in the passenger seat, dressed in jeans, T- shirt, and bare feet. He never seemed to wear shoes. He lighted up a number. (Rick and Jim Manczarek had since quit the band, and I brought in guitarist Robby Krieger, whom I’d played with before.)

“I’m lonely up here,” Jim Morrison said. “I need some love.” He bowed his head and I thought of Pam. Now I felt sad and embarrassed for Jim. He shouldn’t show that much vulnerability.”

“What do you think of the name ‘the Doors’?” Jim asked while turning around and handing me the joint.

“Hmm… it’s short and simple,” I responded, taking it from him. “Aren’t you paranoid about smoking in the car?”

Jim shrugged his shoulders. I took a short drag and handed it back in a hurry.

“Keep that roach down, would you, guys?” Ray chimed in. “And give me a hit.” Morrison held the joint up to Ray’s lips and he took a huge toke. “Jim got the idea for the name from the Huxley book, The Doors of Perception.”

“The Doors.” I ran it over in my mind. “I like it. It’s different. It sounds odd.” Huxley, I thought to myself, I’ve heard of him. Better read that book.

Morrison explained that Huxley had gotten the phrase from William Blake. “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” When I heard that, I was convinced we had a legitimate poet in the band.

The Doors. I liked the bluntness of it.

“What do you think we should wear?” Jim continued with a straight face. “How about wearing suits?”

“I don’t know… let’s see what evolves,” I muttered, thinking to myself that Jim’s wardrobe suggestion was the worst ever.

Sometimes Jim was so naive, I thought. Some of his Jacksonville, Florida, roots were showing through. Not too hip. More hick.

The last thing that stood in our way was the army draft. The idea of learning how to kill made me sick. Just as worrisome was the fear that the group would be destroyed if someone was drafted. Vietnam was heating up fast. Several friends had already been called up. I couldn’t figure how our government came to the conclusion that our national security was threatened by Communists going into some Far Eastern country on the other side of the world.

Ray had already been in the service a few years before. He didn’t have to sweat it. I remember the story from his student film, Induction, which was fairly autobiographical. Depressed over a lost girlfriend, Ray had enlisted. (Must have been really down. Must have been some girl!) A year after turning on to grass for the first time and smoking Thai sticks in Asia, Ray wanted out. He swallowed a small ball of aluminum foil, which showed up in his X rays as an ulcer. Then he told them he was homosexual and ·they said go home.

That summer Jim, Robby, and I received our notices to report for our army physicals. Robby’s well-to-do family hired a psychiatrist to write up a letter saying he was unfit. Then they sent him to the draft board in Tucson, Arizona, where the local antidraft movement hadn’t yet made them immune to excuses. I had to go down to the induction center in L.A.; Jim was to follow the next week.

The physical was one of the low points of my life. The headlines in the Los Angeles Times told of the first draft dodger sent to jail. He was a friend of a friend whom I had met once. With that in mind, I had been up for. days taking Methedrine that Robby had thoughtfully provided and reading Kenneth Patchen’s Journal of Albion Moonlight for inspiration. With pacifist rhetoric under my belt and Bob Dylan’s lonesome harmonica playing “With God on Our Side” in the background, I tried to convince myself I had the courage of a Quaker. By the time my parents dropped me off downtown at the induction center, I was a nervous wreck. Wearing a blue-and-pink striped shirt and brown cords that hadn’t been laundered in weeks, I pushed open the swinging doors into the large, noisy army headquarters to await my fate. My clothes smelled so bad I couldn’t stand it myself.

I soon found myself in front of a long table where the completed forms were being collected. A black woman volunteer put out her hand to file my papers. Around 50 years old and bursting out of the seams of her uniform, she had the first warm face I had seen all day. As I handed her my forms, she sensed my dejection and took me aside. Pointing suggestively to the “homosexual tendencies” box on the form, she asked, “Is there anything else you want to check?”

I looked at her, first startled, then hopefully, and she nodded toward the papers as if to say “Check it.” I don’t know whether she honestly thought I was gay or just too brittle for the army. The look in those maternal eyes assured me that if I checked that box I would be spared.

A few hours later I got my classification: 1Y the clerk told me I was supposed to return in a year, but meanwhile I was free! I had wanted a 4F, which meant a permanent deferment, but I wasn’t about to hang around and argue with them.

One more army rejection and the Doors would be unencumbered.

On July 14, Bastille Day, I took Jim downtown for his physical. There was a long line outside the induction center this time, so Jim nonchalantly told me to just come back in a couple of hours. He would be all through by then. I tried to tell him that it had been an all-day affair for me, but he just gave me that wolf grin of his, so I agreed to get something to eat and at least check back. I didn’t want to hang around anyway. I felt nervous just being in a military area.

At high noon I returned and, sure enough, there he was standing in front of the entrance looking cool as ever, leaning against the wall, one leg bent, brushing his hair back on the sides with his hands.

I pulled to the curb and stepped out of the car as he came strolling over casually. “Well? What happened?” I shouted over the traffic. “Are you done? C’mon, give.”

Morrison shrugged his shoulders and said, “No sweat. All finished. They gave me a ‘Z’ classification.” He slipped into the car.

I shook my head in confusion and got into the driver’s seat. “What the hell is a ·z· classification?”

“I don’t know,” he said, baiting me.

I started up the Gazelle, ground it into first, and headed toward Hollywood. “C’mon, Jim, what did you do in there?”

He just flashed his mischievous grin. Goddamn, I thought. This guy’s too much. He’s transcending a trauma that nearly gave me a heart attack. I kept prodding him as we drove across town, but he basked in the mystery. How had he bluffed his way past this one?

“Could you take me over to Rosanna’s apartment in Beverly Hills? I gotta get out of here for a couple of days,” Jim begged.

“Who’s Rosanna?” I asked as we walked to my car.

“This girl. A U.C.L.A. art student.” “Uh-huh!” I teased.

I made a left on Ocean Avenue as we split from Ray and Dorothy’s digs. “It’s off Charlieville, in one of those Spanish duplexes.”

“Right.”

Jim rang the doorbell.

“Oh, it’s you, come.in.” The attractive long-haired blonde sounded surprised. Apparently Jim hadn’t called.

“This is John.” “Hi.”

“Hi.”

Jim went straight to the kitchen table, took out a bag of grass, and started rolling joints. He acted like he lived there.

Rosanna responded with loaded sarcasm. “Help yourself, Jim.” Maybe Jim had met his match? She seemed to enjoy the verbal bantering.

“I’ll be back in a little while,” I said, feeling claustrophobic from the mounting tension.

I drove around the shopping district and stopped at a liquor store for some apple juice. Was Jim going to sleep there? I decided to check on the way home.

The door opened as I knocked, not having been shut completely. I pushed it open the rest of the way and saw Jim standing in the living room holding a large kitchen knife to Rosanna’s stomach. A couple of buttons popped on her blouse as Jim twisted her arm behind her back.

My pulse tripled.

“What do we have here?” I exclaimed, trying to defuse the situation.

“Quite an unusual way of seducing someone, Jim.”

Jim looked at me with surprise and let Rosanna go. “Just having a little fun.”

Rosanna’s expression changed from fear and rage to relief. Jim put the knife down.

I’m in a band with a psychotic. I’m in a band with a psychotic!

I’m in a room with a psychotic.

“Well, I’ve gotta go… Do you wanna ride?”

“Naw.”

I made a hasty exit. I was worried about Rosanna, but I was more worried about myself. There was definitely sexual tension in the room as well as violent tension. That’s how I rationalized leaving. I drove to my parents’ house in a daze. Why was I in a band with a crazy person? I wanted to tell someone, my parents, anyone… but I knew I couldn’t. The Doors was my only ticket out of my family and a possible career in something I loved, and if whoever I related the incident to reacted by saying I should quit, I would have no options. School offered me no options; there was nothing else I was interested in. I tried to forget the knife incident. But problems come back one way or another when not dealt with. A rash that itched constantly developed on my legs.

By the beginning of 1966, the marquee of the London Fog read “The Doors.” We had made it to the Sunset Strip. After hitting the clubs along the Strip, we talked the owner of the Fog into booking us for a month, after we packed the house with friends. Our first real gig. Underneath our name we had them add “The Band From Venice.” The place was a dump and a hangout for misfits, but it was on the same block as the Whiskey A Go-Go, so we were game.

Jim’s stage presence had a ways to go; he rarely faced the audience. We had a discussion one night after a lame set and confronted Jim with his shyness. We suggested to him that he try to turn around and face the people more often, which he accepted with no comment. We were used to facing each other in rehearsals, and Jim wasn’t secure enough yet to break that circle of energy. He also didn’t take nonmusical suggestions well.

Ray tells a story about when Jim was still living at his and Dorothy’s apartment and he suggested that Jim might look better if he got a haircut. Jim’s reaction was to scream at Ray never ever again to tell him what to do.

“I just told him to get a simple haircut,” Ray relayed to me later. “I’m never going .to try that again.” Usually Ray came on as Mr. Confidence, flamboyant and articulate, but something in that confrontation took the wind out of his sails. It was a shock for Ray to be rebuked after bringing Jim so far. On the other hand, Jim wasn’t going to take any advice from “Dad,” and Ray was six or seven years older than the rest of us and hung out with Dorothy all the time. With a navy admiral for a father, Jim was sensitive to receiving criticism and interpreted any suggestions as orders from an archetypal father figure.

A few weeks after the haircut comment, Jim moved into an apartment in Venice with his U.C.L.A. film school buddy Phil Oleno and struck up with a new group of friends.

Ray had managed to get himself a beach house at the band’s expense. Meanwhile, Robby, Jim, and I walked the streets, looking for more gigs to pay the rent. Ray refused to join us, saying it was a waste of time. He was right. It was a waste of time inquiring at sleazy bars on Hollywood Boulevard that had never ever had live music, but the three of us were frustrated, and by going out it felt like we were doing something. Inevitably the resentment surfaced. Jim began grumbling about the “old fucker, all warm and cozy with his ‘wife’ at the beach.” We began cruising over to use the beach house at odd hours, like six in the morning. After all, Ray had said we should treat it as our own, so…

One morning after our gig at the Fog, Jim and Robby paid Ray and Dorothy a visit at dawn — on acid. They brought a couple of hookers we knew from the club. (None of us had partaken.) As the story goes, when they walked in they heard the familiar sound of Ray and Dorothy getting it on. (I say familiar because Jim, having lived with them, would often imitate the sound of Ray groaning and Dorothy saying, “Oh, Ray, oh, God, oh, Ray, oh, God.”)

Peaking on a double dose of pure sunshine acid, Jim began laughing and poking at Robby while gesturing to the noisy bedroom. He stumbled over to Ray‘s prized record collection and started taking records out of their jackets and throwing them across the massive room. Ray came out as Jim was walking on the records and said — carefully — “Okay, you guys, the party’s over.”

Robby giggled nervously in the background. The hookers slunk out of the room and headed for the water. Jim stood there with a glazed look on his face. Around his feet lay broken records with his sandy footprints on them. Ray’s jaw tightened.

It was another standoff. Living side by side with Ray and Dorothy in two rooms for the previous year had had its effects. Jim had turned them into surrogate parents, and now he was breaking away.

The summer of 1967 was one of traveling the country from coast to coast, from gig to gig, studio session to studio session. We were trying to crack New York again, appearing at the Scene in June while the Monterey Pop Festival, the first of its kind, was going on in California. I was depressed that we were in this dumpy club across the country while all of the important groups of the sixties were in Monterey. Of course, we weren’t even invited! Later our PR man Derek Taylor was to say that we’d been overlooked. Bullshit. They knew about us. They were afraid of us. We didn’t represent the attitude of the festival: peace and love and flower power. We represented the shadow side. My flower-child half strongly wanted to be tripping and dancing at the festival, but I was in the demon Doors.

Jae Holzman, who was, after all, president of a folk label (Elektra), had had Paul Simon over for dinner and played him some of our demos for our second album. He told Paul the Doors were going to be the biggest group in America, and Simon agreed. Simon also agreed to have us play second bill with Simon and Garfunkel at Forest Hills. Ten thousand people!

You could feel our nervousness backstage when Paul came in to wish us luck. He was very friendly. I don’t know whether it was nervousness, or just that Jim hated folk music, but he gave Simon the worst vibes, in short of saying “Get the fuck out of our dressing room.” To the guy who hired us! Then we went out onstage and Jim didn’t give an inch. He didn’t try to connect to the audience in any way. At the end of our set, during the “Father, I want to kill you” section, Jim put all the bottled-up hatred and rage and whatever was bothering him into slamming the mike down and screaming. It lasted about one minute. The audience woke up a bit and started thinking about what they were seeing. After intermission, Paul and Arty walked out onstage to thunderous applause.

In July “Light My Fire” hit No. 1 on the charts and stayed at No. 1 for a month. It remained on the charts for an unheard-of 26 weeks. A rumor spread like brushfire that it was the anthem for race riots in Detroit that summer.

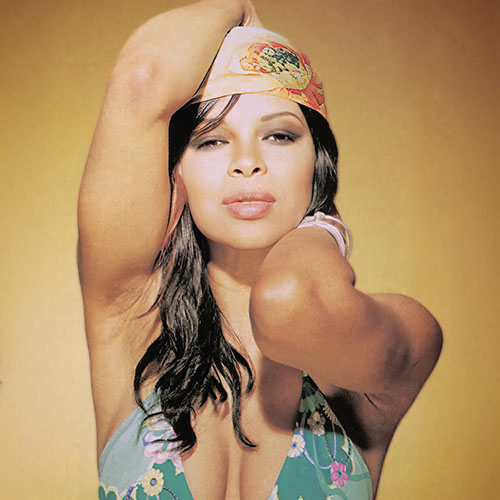

The recording of our second album, Strange Days, began very well. We were refining our so-called California sound, with “spooking organ tones, the traces of raga and sitar…” as a rock writer described it at the time. And Jim’s lyrics kept astounding me.

His stuff was great — erotic, but not pornographic; mystical, but not pretentious. His poetry was a source of his power as much as his sexually charged “David” looks or his “brass-and-leather voice.”

During the recording of the Strange Days album, Morrison’s attitude was more confident. For all of us, the studio was becoming a familiar place; we were more relaxed there. It was almost like a second home. Bruce Botnick, our engineer, was using more and more microphones on my drums, which my ego liked. Getting a “sound” on the drums still took forever. I had to play each drum and cymbal over and over individually in simple, monotonous patterns until Paul Rothchild, our producer, was satisfied with what he heard. I, too, wanted a fat drum sound, but I felt it didn’t warrant half a day’s work.

Because of glitches like these, Jim started avoiding the sessions until he absolutely had to be there. When he did arrive, there was incredible tension in the room for a while, but no one expressed his anger over Jim’s rudeness or tardiness.

One night we were smoking a bunch of hashish and mixing “You’re Lost Little Girl” down to the final two tracks for stereo. Ray came back into the control room from the hallway, where he occasionally listened to the playback with the door ajar. He was trying to “distance” himself from the sound, which we had heard over and over, to gain some objectivity. Plus, Rothchild usually blasted the playbacks.

“I think your song, Robby, is perfect for Frank Sinatra,” Ray suggested with his tongue thoroughly inserted in his cheek.

“Frank should dedicate it to his wife, Mia Farrow.”

‘Rosanna’s expression changed from fear and rage to relief. Jim put the knife down. I thought: “I’m in a band with a psychotic! I’m in a room with a psychotic!”’

We all chuckled. The vocal had a serene quality, which may have been due to Rothchild’s idea of having Jim’s girlfriend Pam come down and give head to Jim while he sang. On one particular vocal take, Jim stopped singing in the middle of the song and we heard some rustling noises. Rothchild appropriately dimmed the lights in the vocal booth, and who knows what was going on in there? We went with a later take, but Paul’s idea may have affected the vocal we went with. It had a tranquil mood, like the aftermath of a large explosion.

When we finished mixing “You’re Lost Little Girl,” we listened to it twice again, at extremely high volume. It sounded great.

The Strange Days kept getting stranger. By September Jim was beginning a secret life of his own, so secret that years later I learned that he had participated in a witch wedding. Jim would have several hours to kill while we were overdubbing on the instrumental tracks before we needed him to replace any work vocals, so he would run out to a bar or pick up someone and they’d get wrecked on downers and alcohol. Sometimes Jim asked me to go out drinking with him after our sessions. But I couldn’t do it. I felt it would be hard to resist the peer pressure to drink, so I declined the invitations. When you meet someone and he becomes your brother, and you create stuff together that is possibly greater than your individual parts, you’ll go down the road a little farther with that person than you should because you love him. But accepting would have meant compromising something inside me. Jim was becoming so unpredictable and so unreliable, I even began begging Vince, our roadie, to pour out any liquor he found lying around backstage or in the rehearsal room.

Coming home late after one of the Strange Days sessions, Robby and I walked into our place and it was a wreck. We wondered for about 30 seconds who’d done it, and then thought of Jim. It turned out that he’d taken one final acid trip before truly committing to booze. Pam had joined him in the excursion, and they’d ventured next door to our apartment… and freaked out. Jim got the idea to piss on my bed. I was livid. Robby thought it was funny. Sigmund Freud would have had a field day. At times like those, I wondered what Ray was doing — hiding with Dorothy while we baby-sat?

Cancel my subscription, Jack. Morrison wasn’t only “writing as if Edgar Allan Poe had blown back as a hippie,” as Kurt Von Meir wrote in Vogue, he was living like him — headed straight for a sad death in a gutter.

The psychedelic Jim I had known just a year earlier, the one who was constantly coming up with colorful answers to universal questions, was being slowly tortured by something we didn’t understand. But you don’t question the universe before breakfast for years and not pay a price. What was worse, his response to his demons was becoming glamorized.

In an interview with Time magazine, Jim labeled us “erotic politicians,” a tag I loved; in turn, they called the Doors “black priests of the Great Society” and Jim the “Dionysus of Rock ‘n’ Roll.”

And the more secretive Morrison’s personal life became, the larger the legend grew.

March 1969. “There’s a point beyond which we cannot return. That is the point that must be reached,” Kafka once wrote. Morrison had finally reached it. He had become the beetle. He had metamorphosed into a monster that could still charm.

Until Miami. His charmed life ended in Miami.

What was it that drove Jim to the abyss and then made him jump that night, in his home state? He certainly had been born with some extra intensity or inner demons.

He was a precocious kid with a military upbringing. Travel City. Rumors of an aggressive mother, which were semi confirmed when she came to see us play at the Washington Hilton back in ‘67. Jim hid from her the whole night, but she made herself ever-present, ordering the light crew to do a good job on her son’s show.

The Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami was sweltering with all those extra people they stuffed in by taking out the seats. It was 8:15 PM. We were supposed to go on 15 minutes earlier, and there was still no sight of Jim. I was swearing at the fucker in my head.

“Should we go on without him?” Robby said.

“No!” I shouted, trying to stall for time. This weren’t no sensitive European crowd. These people sounded rowdy, and I was sure they wanted the Doors with their hometown boy singing up front. I was livid. I busied myself with a drummer’s stretching exercise holding my arms straight out with the butt end of my sticks together in the palms of my hands and twisting my wrists upside-down.

Finally Vince came running up the stairs to the dressing room shouting “He’s here” I turned my back in order not to have eye contact as I felt the presence of someone coming into the room with an entirely different vibration than everyone else. You could literally feel the chaos. It’s what the press called “charisma.” I call it psychosis.

I didn’t look at Jim because I was afraid of him. I was so mad I wanted to punch him, and at the same time I was scared of saying anything hostile to him. When one gains so much power that others, friends as well as strangers, are afraid to comment on one’s excesses, trouble lies ahead.

Robby frowned at our manager Bill Siddons, and Ray, usually the patient one, Just mumbled, “Let’s do it.”

Jim was drunk on his ass.

As we descended the stairs, it felt like entering a sauna. Dante’s inferno. Later I was to find out that there were over 13,000 people stuffed into the place, meant to hold 7,000. Vince had hired some locals to stand at the door with metal customer-counters. As we stepped onto the stage, Vince warned us that it was poorly constructed. Ray sets the scene: John, Robby, and I didn’t know what Jim would do. We’d follow him into the jaws of the hellhound itself, if we had to, ‘cause this is Jim, this is our man, this is our main man — the poet.”

We started “Back Door Man,” and Jim sang a few lines and suddenly stopped. We vamped for a while but soon petered out. Then Jim went into a drunken rap:

“You’re all a bunch of fuckin’ idiots. You let people tell you what you’re gonna do. Let people push you around. You love it, don’t ya? Maybe you love gettin’ your face shoved in shit. You’re all a bunch of slaves. What are you going to do about it? What are you gonna do?”

I wanted to turn into liquid and dissolve into the spaces between my drums. I had never heard such rage directed at an audience.

He continued. “Hey, I’m not talkin’ about revolution. I’m not talkin’ about no demonstration. I’m talkin’ about havin’ some fun. I’m talkin’ about dancin’. I’m talkin’ about love your neighbor till it hurts. I’m talkin’ about grab your friend. I’m talkin’ about some love. Love, love, love, love, love, love, love. Grab yer friend and love him. Come oooaaann. Yeaaahhh!”

If only I could have melted down and hid behind my bass drum. I was small enough to fit down there. If I crouched. I didn’t move. Jim’s inspiration came from seeing Julian and Judith (Malina) Beck’s Living Theater a few nights previously at the University of Southern California. They were a confrontational performance group that got Jim’s creative juices flowing again and scared the shit out of me. Jim had gotten tickets for everybody around our office. He really wanted us to see what they were up to. At the Living Theater performance, actors wore a minimal amount of clothing, G-strings and the like, and climbed up the aisles and over the audience shouting “No passports! No borders! Paradise now!” I was intimidated. Jim was elated.

“Hey, what are you all doing here? You want music. No, that’s not what you really want. Alright, I want to see some action up here, I wanna see some people up here havin’ some fun. I wanna see some dancin’. There are no rules, no limits, no laws, come on! Won’t somebody come up here and love my ass? Come on. I’m lonely up here, I need some love.

He bowed his head and I thought of Pam. Now I felt sad and embarrassed for Jim. He shouldn’t show that much vulnerability.

Miami was one of Jim’s last attempts to get a new creative spark going and to quell the demons that had had him off-center from birth.

Of course, neither the band nor the audience knew what Jim was up to. He hadn’t told us about taking acid right before the Hollywood Bowl, and he hadn’t mentioned how this night he was going to try to inject confrontational theater into our performance.

Musically, the concert was the worst ever. After several attempts at playing our songs, during which someone from the audience threw a gallon of orange fluorescent Day-Glo paint on us, Robby and I got up from our instruments and started to leave. The left side of the stage made a cracking noise and dropped several inches.

Vince Treanor relives the next few moments: “Somebody jumped up and poured champagne on Jim, so he took his shirt off. He was soaking wet. ‘Let’s see a little skin, let’s get naked,’ said he, and the clothes started to come off. I’m referring to the audience.”

At this point Jim lured many fans up onto the stage, forming a circle, locking arms and dancing. A policeman had exchanged his hat for Jim’s skull-and cross bones hat onstage. Then they each threw them into the audience.

Then Jim hinted that he was going to strip all the way. “You didn’t come here for music. You came for something else. Something greater than you’ve ever seen.” Ray yelled at Vince to stop him. Vince continues: “I went out past the high hat and John’s snare, up behind Jim, and I put my fingers into his belt loops, twisting them, so he couldn’t unbuckle or unsnap them.”

I decided to bail. As I jumped off the stage and accidentally landed on the light board, which fell to the ground, a security guard flipped Jim like a blackbelt karate expert, head over heels into the audience, thinking he was a fan.

Scared shitless, Robby and I ran up the stairs to get out of the chaos. Jim was now in the middle of the auditorium, leading a snake dance with 10,000 people following him. I looked down from the balcony, and the audience looked like a giant whirlpool with Jim at the center. As I went into the dressing room, Bill came racing out.

“Get him out of there!” I warned. “He could get hurt!”

“That’s what I’m going to do!” Bill screamed.

Ten minutes later the Lizard King strolled in with a group of people laughing and talking. He was sober now, a concert being better for a hangover than drinking several cups of coffee I

My anger over the performance was subsiding as Ray and I looked out the window at the crowd driving away. “Do you feel the energy out there?” Ray remarked. I noticed that there was a higher sort of buzzing of conversation as the people drove away.

“The hookers slunk out of the room. Jim stood there with a glazed look on his face. Around his feet lay broken records with his sandy footprints on them.”

“They’re pretty charged up out there, as if we gave them an energy jolt and they’re going to take it out into the streets,” Ray continued.

“Yeah, I feel it,” I replied, thinking that even though we’d played poorly, it had been theatrical. I looked over at Robby, who was pecking at the spread of food laid out for us. He seemed to have accepted what just went down onstage. There was one thought that I couldn’t get out of my mind, though. How long were we going to get away with this? The ledge at the top of our pedestal was getting narrower.

On the plane from Miami to our Jamaican vacation, Jim told us that he had gotten out of New Orleans late because of a fight with Pam. Making a stab at a romantic vacation, he had rented an old Jamaican plantation house, but now he went there alone instead. It rested high atop a tropical hill, complete with slavery vibes. A few days later Jim showed up at our place. Robby and I and our respective mates, Lynn and Julia, had rented a big house on the water. Jim said his short stay up on the hill had been “spooky.” He described sitting in the dining room at the end of a long table, eating, while the help sat in chairs along the walls, waiting to be called on. The bedrooms had lace curtains over the beds to keep the bugs out.

I felt sorry for Jim, alone up there, but I was bugged that he crashed our hideaway. He was drunk on rum, and his presence unnerved me. He knew that my bad vibes were directed toward his self-destruction, but it was clear to both of us that nothing was going to stop him. After a few days, Jim left for the States, but not before Bill called and said warrants had been issued for Jim’s arrest. He’d been charged with lewd and lascivious behavior, simulating oral copulation, and indecent exposure. I couldn’t believe the charges! Yes, Jim had been drunk. But simulating oral copulation? They must have been alluding to Jim getting down on his knees to get a closer look at Robby’s fingers as he played guitar. Since he didn’t play an instrument, he was enamored of musicians. Later a photograph was used as evidence of this obscene act of fellatio on Robby, which was actually Jim honoring Robby’s talent. No absence of malice in Miami. They insisted that Jim was giving Robby head.

When the warrant was issued, Jim left Jamaica and returned to L.A. Our entire 20-city tour was canceled. Paul Rothchild describes the scene at our office: “They couldn’t get a job. Promoters all over the country were canceling the shows as fast as the Doors could answer the telephone. There was a horrible two weeks where the bottom fell out.”

Why did the world want to believe — so badly — that Jim had exposed himself? If one finds someone else to blame heavily, then one doesn’t have to look closely at one’s own neuroses. My theory is that some parents got curious about their kids coming home half clothed, called the local politicians, and they decided to use Jim as an example of moral decay. Or it was some righting bullshit plot. Fucking politics.

I must have known all along it was going to end like this. I reacted schizophrenically Half of me hated him, like Ishmael hating Ahab, for taking us down; the other half said, “It could be for the better, all for the better.” I was glad that he was tearing it all down, because I knew it was defective. As Billy James said under his breath while writing out our first bias for Elektra, “Too much power in Jim’s hands could be dangerous.” He must have sensed the chaos early.