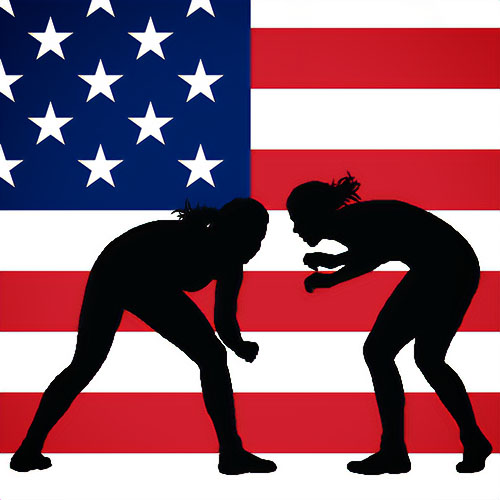

The once tranquil pool water is suddenly roiled by frantic creatures darting back and forth like a gaggle of piranhas, as if the last morsel of flesh has just been flung at them

Human Piranhas of Rugby

They’re pulling and kicking, desperately fighting for possession. The fact that they can spend so much time underwater while exerting so much energy is astounding — especially when you consider that these are people, not fish.

No gills here. Now and again an odd warrior or two will rise to the surface, take in some air, and return to the fight below. It’s difficult to figure out what’s going on, hard to see past all the kicking legs. There’s one guy who has six other guys hanging off him. He’s straining to pry open his arms and kick his way free. One of the attackers rises to the surface and leaves the pool, and a replacement dives in, getting kicked in the face as he enters the fray. Finally a ball is dropped into the middle of this and all the piranhas go after it. Within seconds they’re on their way to the metal basket at one end of the pool. A guy lies down on top of it to prevent it from being penetrated, but this is of little use. The guy in possession of the ball hits the blocker hard with his shoulder, pummels him off the basket, and dunks the ball. All of the swimmers rise, gasping as soon as their mouths breach the surface — amid the cheers and rants of the spectators.

No doubt about it: What’s most surprising about underwater rugby is the violence. There are some rules — you can’t attack an opponent by his mask or snorkel, you can’t pull down his trunks, you can’t intentionally kick an opponent. But here at the Underwater Rugby World Championship, this last rule seems to be the least observed. In fact, somebody on the Russian team was kicked in the face just now as he went in for the attack. Pain registers across his features, but not for long. It’s hard to work out if the kicks are intentional, because players are constantly kicking their legs to propel through the water.

“Most injuries are small,” says the Danish national team’s Jorn Christoffersen. “The density [of the water] slows everything down. The most common injuries are broken fingers from when people try to pry your hands . off the ball. Or bruised knees from trying to get the goal-keeper off the basket. I lost a tooth recently, but that was when my head was out of the water and the ball hit me in the face.”

There’s much hearsay as to underwater rugby’s origins. Some say it was a game played in Kenya with coconuts. Others say the French navy developed it as a training activity. Actually, underwater rugby was invented in Germany in 1961 by Ludwig van Bersuda, mainly as a warmup activity for swim clubs. Then Dr. Franz Josef Grimmeisen of DUC Duisburg swim club envisioned it as a competitive sport. Grimmeisen arranged the first underwater-rugby matchup in October 1964, between DLRG Muellheim swim club and DUC Duisburg. The sport’s premiere received half ·a page and two photos in the local paper. Soon the game spread to Scandinavia and elsewhere, until there were leagues all over the world.

Today, plans are on the table to take the sport mainstream. “We are meeting with other underwater-sports federations to talk about hosting joint world championships,” says Soren Neubert of Denmark, president of the Underwater Rugby Commission. “This way we hope to attract more competitors, more spectators, but more important, more media. The combining of several disciplines means we can make a much bigger event and draw much more attention.”

“The pool looks like a fish tank at reeding time. Players dart about in all directions, clinging on, grabbing legs.”

It is the three-dimensionality of the arena that makes underwater rugby so unique. Football and baseball are played on a field, hockey on the ice; underwater rugby is played in a 26-foot-square pool as much as 16 feet deep. The ball is made of rubber and, instead of air, is filled with saltwater, which gives it a greater density, making it sink slowly rather than shoot to the surface. A basket floats at each end of the pool. Players supply the rest of the equipment: healthy lungs and a big set of cojones.

This is not a sport for the faint-hearted. Games consist of two 15-minute periods that demand full-on physical exertion and contact. As in ice hockey, players can be substituted at will. When a player can take no more, he will rise to the surface, using his last push of energy to get out of the water so that his replacement can dive in.

When in the water, a player will likely surface two or three times for air before wearing out and exiting the pool for a rest. Substitutions work on a rotary basis. Once exited from the pool, you go to the back of a line; players enter the game from the front of the line. Rest periods vary, depending on the way the game is going. You could join the back of the substitution queue one second and be diving in from the front of the queue within a minute.

When you’re in the pool, “you use around 90 percent of your full limit,” says Christoffersen, a 12-year veteran of the game. “You have to be careful because your adrenaline is high; you’re really boosted when you come out of the water for a break, and you have to try to control this because you need to get your energy back before you enter the water again. Sometimes you break for two minutes, other times half a minute. The discipline is to never use more energy than you need, because you will always need it later. Never use more than you can recover. You always have to think about how and when to use your power. So it’s really a mental strain as well as a physical one.”

A player who fails to keep some energy in reserve will often black out in the water. Knowing he has nothing left in him, he will nonetheless go for it when he sees an opportunity to score. It’s not uncommon for said player to wake up on the sideline moments later, being slapped alert by a physician.

Eleven teams from all over the globe have come to Fredericia, Denmark, for the Underwater Rugby World Championship. Players hang out around the pool, waiting for their matches. It’s no surprise that they are in amazing shape; most train six days a week as they head into the championship season.

For years the Scandinavians have dominated the sport, and Sweden and Norway are set to square off in the finals. It’s always a spectacle when teams of this caliber face each other. In the most grueling battles, players often get benched for fouls. For such offenses as headlocks, throat or groin grabbing, and bending back an opponent’s fingers, a player is sent out for two minutes.

Penalty shots are rampant. They are a 45-second showdown between an attacker and the defending goalkeeper, who, using his biggest and best means of defense — his body — tries to cover the goal by lying on it. Goalkeepers are not allowed to hold onto the basket or the pool’s edge, so they must stay underwater using only their own physical power. All the while the goalie is fending off the attacker, who’s trying to drag him away from the basket. This makes players seem more like underwater gladiators than mere athletes. If the goalkeeper manages to get the ball himself, he can rise to the surface with it. As soon as the ball is above the water, the penalty phase is over. But if the goalkeeper doesn’t get the ball out of the water, the attacker has the entire 45 seconds to wrestle him out of the way. Unlike in soccer, where top players make the penalty nine times out of ten, in underwater rugby, it can go either way. The goalkeepers save a shot as often as they concede one.

A big crowd has gathered to watch the men’s final. The players are at the edge of the pool fidgeting anxiously while their coaches go over last-minute tactics.

Finally the start horn blows and the piranhas are back in the water. The fight is on. The initial dash for the ball is usually the biggest battle. Six players from each team arrive at the bottom of the pool at the same time. They all want the ball. Pulling and shoving, the gaggle of combatants is surrounded by bubbles floating to the surface. Some of these bubbles have been knocked out of somebody’s gut, others have been exhaled in the frenzy. Players rise for air, and “refresher” teammates join the game as others, drained of power, exit the pool.

A Swede has possession of the ball, and is trying to evade two opponents. In what could be a fight scene from a James Bond film, competitors twist and turn to get the better of one another. Despite the entanglement, the Swedish player breaks free and heads for the basket. He uses his shoulder to knock the goalkeeper off the basket, then drops the ball in for a point. Everybody in the pool and in the stands is surprised to see such speedy scoring. When teams of this level are matched up, it’s rare to see a point scored so fast.

The pool looks like a fish tank at feeding time. The players dart about in all directions, clinging on, grabbing legs. A player from the Norwegian squad is benched two minutes for entering the pool before his teammate was completely out of the water. In conformity with the rules, the offending player is not replaced; the Swedes try to take advantage of Norway’s diminished manpower, but despite all the fighting and wrestling, they are unable to score a goal before Norway is back up to full strength.

There are three referees monitoring this war, yet I’m still amazed that anybody notices any violation. Often all 12 players are converged in the middle of the pool, fighting and scraping. for possession of the ball. Sure, only the person with the ball can be tackled, but this generally means that he has four guys crawling all over him while his five teammates desperately try to position themselves for a pass. Should somebody in the middle of all this take a swing at an opponent, who can spot it? Yet somehow the refs do.

“Often all 12 players are converged in the middle of the pool, fighting and scraping for possession of the ball.”

Nearly 12 minutes into the first half at Fredericia, there’s a penalty. The Swedish goal-keeper hooked his shoulder into the goal to help him stay firmly in place against the on-coming attack, and the referee called him on it. The misdeed is confirmed with a video playback.

As soon as the horn blows to indicate the end of the 45-second penalty period, the Norwegian player dashes through the water, coming in hard and fast with his right shoulder to hit the goalkeeper. The player moves away from the basket for just a few seconds as the Swedish goalie does everything he can to protect the basket. The Norwegian — shouldering the keeper all the while — reaches around, and although the ball starts through the mouth of the goal, the Swedish keeper manages to reach in and pick it out before it goes all the way through. The Swedes are going crazy, rejoicing in the fact that they’ve retained their lead … for the moment, anyway. They celebrate more when, after 13 minutes and 50 seconds, they again score against their adversaries in a battle of hard shoulder knocks that sends one Norwegian player out of the fray with an injury.

Through the start of the second half, both teams push hard. Back and forth they go. Almost eight minutes into the period, Norway scores. They make a break, and the player with the ball hits the goal-keeper hard, moving him off the basket. The Swedes, concerned that they might lose their lead, call a time-out to discuss strategy. It’s a talk that works, for although Norway pushes hard right until the final second, the team falls short.

The horn blows to signal the end of the game, the crowd cheers, and, for the fourth time in a row, the Swedes are the world champions of underwater rugby, this most bizarre of bizarre sports.

Here some 20 years later, they apparently still compete in this strange athletic competition. Now we do not wish to judge how people spend their time in Australia, but should you simply be planning a visit, we will mention that it might be easier to appreciate the view spending some time at Bondi Beach. Most of the sport there takes place above water where people can see and appreciate it.