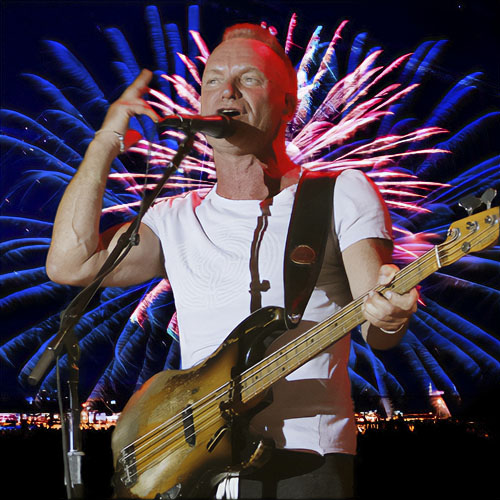

I never want to lose contact with my real fans. That’s why I do so much touring. It’s nice to know what the moguls are thinking, but it’s just as important to keep listening to the waitresses in honky-tonks.

“On the Road Again…” Still

Through thousands of hard, dusty miles and years of frustrations, Willie Nelson hit the roads of Texas in old station wagons and rumpled sleeping bags. Now Nelson and his “family” of pickers and pranksters travel on luxury buses and Lear-jets. Willie knows all about being broke and lonely, and many of his best songs take the form of anguished autobiography: “The night life ain’t no good life, but it’s my life.” But he seldom writes these days. He is too busy drinking in the cheers of huge audiences and accepting the accolades and embraces of Hollywood moguls. “It’s been rough and rocky traveling,” Willie sings in his well-known “Me and Paul.” But the road has at last taken him all the way from honky-tonks, where stages were fenced with chicken wire to ward off flying beer bottles, to — among other places — the lawn of the Jimmy Carter White House.

At forty-five, the little guy with the red beard, ponytail, and single earring has emerged as a very hot show business property. He is a dominant figure in country music, a budding movie personality, and a kind of cult hero to an unlikely following of beer-swilling rednecks, pot-smoking hippies, and millions in between. But even as he savors the hit records and screen roles and hard-earned fame, it sometimes seems easier to explain how he came this far than it is to figure out why.

Nelson himself offers no simple answer. “I’ve been writing and singing pretty much the same kinds of things for twenty-five years,” he says. “It seems like a lot of folks have just gotten around to listening.” Actually, people in the music business listened and liked Nelson’s songs from the beginning of his career. They just didn’t want him to sing them. Early classics like “The Night Life,” “Crazy,” and “Hello, Walls” became solid hits in the popular and country fields — but they were hits for other artists. Nashville executives never could see a place for Willie’s own husky, plaintive voice, and so his own records tended to be overproduced, underpromoted, and seldom sold.

The breakthrough began in the early 1970’s, after Nelson gave up pounding studio doors in Nashville and returned to his native Texas. In 1972 he threw the first of his annual Fourth of July picnics — and some 50,000 fans showed up in Dripping Springs, near his Austin home. More important, visitors to the picnics cheered rock groups as well as: country stars, and the media noticed that Willie’s fans and friends came in all age groups and hairstyles. Soon he was being hailed as a great synthesizer and a leader of a broader new movement, known variously as “progressive rock,’’ “country rock,” and “redneck rock.”

During the same period, Nelson turned his musical talents to a series of theme or “concept” albums. The first, and the one Nelson still considers among his best, was Yesterday’s Wine. With strong overtones from the tabernacle choir in Nelson’s tiny hometown of Abbott, the album told the life story of a man from his birth — “What would you have me to do, Lord?” — to his death, when he looks at his own funeral with brilliant irony. As his neighbors surround the casket and talk of his fast nightlife, Nelson sings ruefully, “If I’d listened to them, I wouldn’t be here.” This all proved too deep for most record executives and country music fans, but it offered one important clue to understanding Nelson. “I’ve sort of written my autobiography,” he says. “I’ve just disguised it as a bunch of songs.”

Drawing on the rich experiences of his own two stormy divorces, Nelson then created the album Phases and Stages, an evocative look at a broken marriage from both the man’s and woman’s point of view. Along with another rock-oriented album, Shotgun Willie, that work paved the way for the fulfillment of a dream. Columbia offered Nelson a contract giving him full artistic control of his albums.

Given that chance, Willie promptly broke all the rules. Stringing together some old songs that he had once sung to his three kids at bedtime, he created an Old West tale of love and murder called Redheaded Stranger. Columbia executives winced when they heard the spare, starkly produced sound. But the album went platinum, the old Fred Rose ballad “Blue Eyes Cryin’ in the Rain” became a crossover single hit, and Universal. bought the rights to make Redheaded Stranger into a movie. Now Nelson had still another image: he was the musical outlaw who had shown that he could beat the system.

Then, with the fierce innocence and vaguely contrary spirit that have always confused those who would give him a narrow label, Willie took another sharp turn. His Stardust album was a country-blues adaptation of ten of the standards he had enjoyed in his youth. Last year it became his biggest hit of all.

Now Nelson is deep into another phase of his career. He has completed his first film role, as a supporting actor to Robert Redford and Jane Fonda in The Electric Horseman. Director Sidney Pollack was so impressed with that effort that he signed Willie to star in another movie, Honeysuckle Rose. And Universal executive Thom Mount, the first to call Hollywood’s attention to the Nelson phenomenon, will soon begin Redheaded Stranger. The old outlaw who once trudged the streets of Nashville in despair is suddenly standing astride the most fashionable hills of Beverly.

That’s how Willie got here. But the question remains, Why Willie Nelson? People who view him as the synthesizer with the grand design for society tend to be surprised when they encounter a quiet man whose driving ambition seems to be picking and singing the songs he has always loved best. Seekers of a dangerous outlaw may be disappointed to learn that Willie’s wildest crimes run to smoking marijuana and occasionally submerging himself in a bottle of tequila. For a man who is supposed to be a cult hero with a message, Nelson does a lot more listening than talking; and in trying to understand his vast appeal and understated wisdom, it helps to go back to his songs:

My front tracks are headed for a cold water well,

And my back tracks are covered with snow.

And sometimes it’s heaven,

And sometimes it’s hell,

And sometimes I don’t even know.Heaven and Hell

The highs and lows began early for Nelson, soon after he and his older sister, Bobbie, learned music from their grandmother and began playing as kids in tiny clubs near Abbott. When he was eighteen, Willie married Martha Mathews, a sixteen-year-old carhop in a hamburger joint in nearby Waco. Then he went on the road to seek his fortune in music — and try to keep eating at the same time. His travels took him around Texas, then west to California and Oregon. When he wasn’t grabbing disc jockey jobs or hustling his songs, he sold encyclopedias door to door or trimmed trees. But within a few years, inevitably, he had to try his luck in Nashville.

If, like a Greek dramatist, Willie had to seek wisdom through suffering, Nashville was the right place to be. He had sold his first hit, “Family Bible,” for just fifty dollars to some friends in Texas. On Music Row he did better, making some decent profits with his writing. But he had a knack for pouring the cash over the bar slightly faster than he could earn it, and he remained bitter about his failure to become a recording star. Once he became so despondent that — in what must surely be one of the world’s more bizarre suicide attempts — he lay down in the street outside Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, waiting to be run over. His wife, Martha, and some friends dragged him to safety. And that was a surprise in itself — there were many nights when Martha might not have bothered.

“Martha was a full-blooded Cherokee,” says Willie, “and we replayed Custer’s Last Stand almost every night.” Once Martha threw a fork at him, and it stuck in his rib cage, humming like a tuning fork. At a genteel dinner party, she poured a plate of potatoes and gravy over his head; he went on eating as if nothing had happened. One night, when he stumbled home drunk and passed out in bed, she sewed the sheet tightly over his head and then beat him with a broomstick when he awoke. The marriage provided ten years of bruises and material for sad songs.

With his second wife, Shirley, Willie tried to settle down on a Tennessee farm and raise hogs. He was the worst hog farmer who ever filled a trough. By the time that marriage had run its course - ten more years of material — he had written a song called “What Can You Do to Me Now?” Soon afterward his house burned to the ground. With his present wife, Connie, a statuesque lady, Nelson returned to Texas. His career began to turn around, and even the marriage has worked out. On his third try, Willie seems to have got it right.

Willie and Connie now maintain a home on a mountain just outside Denver, and Willie still owns his ranch near Austin. But his real home is the open road. As Mickey Raphael, the brilliant young harmonica player in the “family,” puts it, “Our mailing address is Show Bus Number One.” Every time Willie and his followers disband for vacations, they find themselves anxious for the comforts and camaraderie of motel rooms and buses. So it was on the road, in California, that Willie sat down by a motel pool to talk to Pete Axthelm, the Newsweek columnist who is writing a book about him (to be published by Viking).

Is it hard to keep being an outlaw when everyone from New York to Hollywood wants to make you richer and more famous?

Nelson: I never really set out to be an outlaw in the first place. So I guess I don’t have to worry about whether I’m still one.

What is your definition of an outlaw?

Nelson: In the record business, it may not be anything but a label that somebody made up to make it easier to sell records. Among those of us who’ve been called outlaws, I know we don’t think of ourselves as being strongly against the law in a real-life sense. I think of an outlaw as a rebel, someone who knows what he wants and isn’t always going to go along with everybody else’s program.

Do you think you let some people down when you fail to fill a role they expect — as an outlaw, a lonely cowboy, or whatever?

Nelson: I guess that does happen. I understand that good stories have beginnings, middles, and endings. Writers like to write good stories, and fans like to read them. But since we outlaws are still alive, we don’t provide a neat ending for a story. That leaves people to make up their own — maybe for their own benefit. That’s why a guy can come to Austin and write about the rise of redneck rock, then come back and sell another article on the fall of redneck rock. When something is successful, a lot of people try to get aboard. That’s all right, in a way. But you can’t take their labels and conclusions any more seriously than you take any other labels.

On the subject of labels or categories, where does your music fit in? Your recent albums have taken several directions. Does that mean you’re less “country”?

Nelson: No. The albums have changed, but I haven’t. I have always liked to play good music, to make people happy. People thought that the Stardust album was a breakthrough into pop music for me. But really, those were songs I played with my older sister, Bobbie, when we were little kids. Playing them doesn’t make us pop, any more than it makes a song like “Blue Skies” a country song.

In a concert I might play an old-fashioned country tune like “San Antonio Rose” or “Blue Eyes Cryin’ in the Rain,” followed by “Stardust” and then our rock-style version of “Whiskey River.” We don’t worry about categories. We just know people like them. It’s just good music.

You and Waylon Jennings sing a warning: “Mamas, don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys.” But growing up western seems to have worked out for you.

Nelson: Sure, I’ve always tried to have a horse nearby to relax. It’s just that there are times when a limo is more convenient.

Redheaded Stranger is a simple tale of frontier morality, which is told from a stern, masculine point of view. It was a daring thing to put on a record. Why do you think that it worked?

Nelson: I think a certain cowboy morality has been with us since the beginnings of this country. Our grandfathers carved out a frontier — that’s what made us. So their type of living always interested me, and I don’t think I’m that different from anybody else. We all went to see Hop-along Cassidy on Saturdays. Most of us still think of the cowboy as a good guy. Of course, the cowboys-and-Indians thing isn’t what it used to be — modern Indians put a stop to that shit. But sheriffs and robbers and ponies and cows are still with us.

You mean that everybody, deep down, wants to be a cowboy?

Nelson: At least for part of a weekend. Maybe they’ll go to a disco Friday and then a shit-kicker joint on Saturday, and then compare and see what they’ve learned.

How do you feel about the cowboy image?

Nelson: It’s a good image. What’s wrong with John Wayne? I think his cowboy image is healthy. I always rooted for John Wayne. Of course, I rooted for Geronimo, too.

Speaking of John Wayne, isn’t part of your appeal? The fact that while so many rock groups are moving toward an asexual or gay image, you are so frankly masculine in your thinking and in your songs?

Nelson: Somebody once said that you’re really three people: first, who you think you are; second, what someone else thinks you are; and, finally, what you really are. So I can’t answer that completely. But, yes, if I had to describe my approach to life, I’d say it was masculine.

Then let’s talk about women.

Nelson: Great. I’m for ’em.

Any special kinds?

Nelson: All of the above. Especially young, pretty ones.

How do you feel about women’s liberation and the changing attitudes of women?

Nelson: I don’t think attitudes have really changed that much. Women and men are almost identical to me, no matter what the current trends may claim. Their thoughts are not that much different. For one example, some people say that women change faster or behave more unpredictably than men. I don’t believe that. I think that men may just be more deceitful about their changing ideas. Women may make their feelings more obvious and thus seem more flighty or unpredictable. They also may be more flagrant, because they’re more convinced that they’re right. But the thoughts and reactions of men and women are similar. It’s just that men are basically more shy about expressing themselves. Except when they’re drunk.

A lot of modern psychologists might dispute your theory. Maybe you’d better explain.

Nelson: Well, this isn’t exactly deep psychology, but I believe that basically, when a man’s looking at a woman and thinking, “Boy, I’d like to fuck you,” she’s probably at least considering the same possibility. Whether they do it or not doesn’t depend on the difference between them. It depends on the circumstances or the morals involved.

Or her husband.

Nelson: Yeah. That can always be a factor.

What about women’s drive for equal opportunity?

Nelson: I think that’s a little off the mark. Maybe women already have the best of it right now. Over the centuries, the fact that women have been physically weaker has caused them to become shrewder and mentally stronger. Compensation. So I think that anyone who underestimates a woman now is making a mistake. I don’t underestimate a woman one bit. I don’t think she needs anything from me, except what I can give her during a show — or maybe afterwards.

Which brings us to the subject of groupies. What about women on the road?

Nelson: How much time we got?

Start with what women mean to you when you’re on the road.

Nelson: You could say that they’re what keeps a lot of us on the road so many years. They’re the perfect audience.

Groupies are the perfect audience?

Nelson: I don’t really like that word. I’d like something more dignified to describe them. Maybe “star-fuckers.” But the truth is that the star-fucking phenomenon gets exaggerated. Because when you’re up front singing, then signing autographs and talking with folks, by the time you get back to the bus, the crop’s been pretty well picked over. So being the star isn’t such a bargain in that area. There’s a song, “Cowboys don’t get lucky every night.” And it happens to be true.

What about wives? You’ve had three. Do you think married women need equality or liberation?

Nelson: I’m not sure. As long as we’re talking in generalities, let’s take the Indians. When we were kids, we studied them and thought the Indian brave had it made. He got to go out hunting, riding through the woods or fishing in a stream all day, while the poor woman had to stay home and cook or sew. But if you’d ever been up in the mountains on horseback, killed a 300-pound deer, and then carried it back down and dressed the son of a bitch and got him in shape to be cooked — well, maybe it wasn’t so bad to be sitting home all the time, making sure the water’s hot.

Three tries at marriage might strike some people as a lot. And yours have pretty much overlapped, with one starting at about the time the other breaks up. Why are you so frantic about being married?

Nelson: I always feel like I need a home base. There’s something in me that makes me want to know that wherever I am and whatever I’m doing, I can always go home to someone, someplace. Truthfully, it’s not so much that I enjoy being there. Usually, when I do go home, after two or three days I’m ready to go back on the road. But the fact that it’s there is good to know.

You spend about 250 days a year on the road. Doesn’t it get boring?

Nelson: The fact that we’re always moving keeps things new. I may do a tour of twenty straight one-night stands. But each city is maybe 300 or 500 miles apart, and the rides between them — the fun on the bus — keep things lively. And we usually know some friends in each place we go to who we’re looking forward to seeing again. There are little inconveniences, but you more or less overcome them when you feel like you’re always moving on.

Speaking of diversions on the road, people are talking about your new ban on cocaine for your band.

Nelson: That’s right. The guys now call themselves the No Blows Blues Band. Our slogan is “if you’re wired, you’re fired.”

Why did you make that rule?

Nelson: I felt the band’s cocaine use was getting out of hand. Some of the guys were spending too much money. It was also affecting their health. When you’re wired, you stay up and party that much longer. Eventually, it can even affect your music. Before that could happen, I just thought I’d let everyone know how I felt and let them make their own decisions. I’m sure everybody hasn’t quit cold. But they have pulled up some, and that’s what I was aiming to get them to do anyway Nobody’s quit, and I haven’t fired nobody.

You don’t do cocaine yourself?

Nelson: No. I don’t like it. It’s a toss-up which is worse: me high on cocaine or drunk on tequila. When I’m drunk, at least I’m funny. Coke doesn’t even make me funny, and if you’re not funny, why do any of that kind of stuff?

You use a lot of marijuana and no coke. Why do you draw such a sharp line between them?

Nelson: Mainly, because of the effects on the body Marijuana has no aftereffects. You get a nice little buzz, and you don’t pay for it later. Cocaine is a different story You pay like hell for it when you get it, and you pay for weeks and months and maybe years after you use it.

In what way?

Nelson: To begin with, it hurts your nose — don’t try to tell me it doesn’t. I know it hurts mine. Of course, I’ve had a bad sinus problem; so maybe I’m a special case. But it hurts me, and I can’t get high on it. Maybe cocaine users around the world will hate me for saying this. Naturally, I believe people can try anything in moderation. But I’ve seen too many people strung out on cocaine. It hurts them, their families, their reputations, their pocketbooks. I’ve seen the same thing happen because of too much whiskey or too much gambling; so I’m not putting cocaine alone in that category. But anything that can ruin your health or your life has got to be bad, and cocaine is just too easily abused. It’s not natural, like marijuana, which grows in the ground.

But the coca leaf grows in the ground.

Nelson: Yeah, to begin with. But by the time cocaine gets to the user, it’s nothing like that coca leaf. Most of it is just the bullshit that dealers cut it with. That’s one of the main things I object to about it — guys throwing good money after bad dope.

Marijuana is illegal in most states. In using it and talking about it so openly, aren’t you taking unnecessary chances?

Nelson: I couldn’t be so hypocritical as to keep quiet about the screwed-up marijuana laws, I’ve known people in Texas, Mexican friends of mine, who have smoked grass for thirty years, and they’re moral, normal people. They’re not crazed. I’ve been doing it for twenty-five years myself, and I can’t see that I’m any more of an idiot than I was when I started. Yet there’s been a law on the books since 1937 that says marijuana is bad. That’s grave injustice. I can’t accept something I think is so wrong, especially. when I enjoy smoking so much myself.

Despite your strong beliefs on the subject, do you ever fear that in some little southern town, some sheriff might decide to make a name for himself by busting you or some of your friends and trying to lose the key for a while?

Nelson: There has been a danger of that, and maybe there still is. There could be some little narc someplace who wants to become a big narc by busting somebody well known. But I can’t go to sleep worrying about it. In most states, possessing marijuana is only a misdemeanor now, and most good law-enforcement people don’t waste time or money enforcing that law. They probably have kids who smoke it. Maybe they smoke it themselves. They know that it’s a stupid law, even if some judges or lawmakers don’t know it.

How important is marijuana to you as a musician?

Nelson: It’s basically a mild tranquilizer, comparable to Valium, I guess. It takes the edge off, makes things go along more smoothly. I guess it affects different people different ways. But the reason I enjoy it is that when I smoke a half-joint or a joint, I don’t get uptight about little things that go wrong.

Does the quantity or quality of marijuana you’ve had on a given night really affect a performance?

Nelson: It only helps in the sense that it might calm me down when I’m upset about something else. All of us who smoke do it for different reasons. We obviously like it, but I don’t think we need it. Eventually, I’d like to think there will be times when it won’t matter at all. Maybe I’ll be retired, sitting in a wood somewhere, fishing, and I might not even want to light up a joint.

Your picnics have done a lot to show that dope and alcohol — and their consumers — can coexist. Did the media exaggerate that happy joining of hippies and rednecks?

Nelson: No, the media were exactly right about that. When Leon Russell and Waylon Jennings and Coach Darrell Royal got together out on that pasture, that was news — maybe you could even call it history. The generation gap was a real thing. There were strong differences of opinion between the older people and the young, and maybe they were even drifting further apart. Through my music I helped to show that both groups could be right about things and share their experiences. The message was that no matter how long your hair was or how red your neck was, you could enjoy the same things. Some people thought that if you smoked a joint, you were a dope fiend. Some kids thought that if you drank beer in a honky-tonk, you were out of touch with the real world. I got both groups together and showed that they could both have a point. And they figured that I had a good point, too.

You’ve played rough honky-tonks, and you’ve played for big crowds of kids. What made you think that you could bring the two audiences together?

Nelson: I always suspected that music could do it. Once they agreed on the music they liked, I figured they could take care of some other stuff.

But there was once a point when the generations couldn’t agree on anything. Kids could lie in a corner with their stereo earphones turned to rock ’n’ roll, and they might go for years without hearing a damn thing that Mom or Dad had to say. The kids had discovered that the grownups had been wrong about something — whether it was the war in Vietnam or the claim that marijuana would make you a raving maniac — and they figured that if the older people had been wrong about one thing, they were probably wrong about everything. They had to be shown that they could still share something. And since they had those earphones on anyway, music was a pretty good place to start.

You really thought you could bridge the generation gap?

Nelson: I didn’t think I could change the world, but I did want to reach the people around me. Once I did that, it seemed to spread a little wider.

Speaking of spreading, you’ve managed to wander among country, rock, and pop in the last few years. A lot of people used to think that that couldn’t be done without compromising or selling out.

Nelson: I never had to compromise or give up my roots. I think the problem is that country music is so good that some people get selfish about it. They want to limit it to their own radio stations or favorite places. Country fans don’t always want everybody to know how good they have it, and record companies respond by keeping the field narrow and going by certain old-fashioned rules. I didn’t change country music. I just invited more people to hear it. I believe that anybody can be a country fan, if you just give him the opportunity.

It took a long time for you to get that chance.

Nelson: A very long time. I spent years playing in joints where the people cheered and danced to old country songs and old standards. Nobody worried about whether each song was country. We just liked good music, and we seemed to agree that we were having a hell of a time. But somewhere between those beer Joints and those offices in Nashville, the good times got lost.

Looking back on your dealings with record companies and Nashville, were you too naive, too trusting?

Nelson: Green is the word. Naive, ignorant — I was all those things. It wasn’t any particular company’s fault. They’re all alike: they go by the profit-and-loss system.

But with the picnics and your recent albums, you beat that system?

Nelson: I’m not sure if I beat it, joined it, or convinced it that I had a point. Probably a little of all those things. But I sure like the result.

If you had it to do over, would you avoid Nashville entirely or do other things differently?

Nelson: No, I think I’d do everything about the same. I’d just try to speed up the whole process.

Now that you’re a Hollywood celebrity, do you ever worry about Willie Nelson losing touch with the honky-tonk people or the kids or any of your other audiences?

Nelson: I never want to lose contact with my real fans. That’s one reason I still do so much touring. I always want to know what the folks want to hear in Lacrosse, Wisconsin, or in Lafayette, Louisiana. It’s nice to know what the moguls are thinking, but it’s just as important to keep listening to the waitresses in the honky-tonks.

Why waitresses?

Nelson: Long before all this happened to me, I depended on those waitresses. Back in Texas, I think every singer in every band had a following of waitresses. It was a natural relationship. Before we ever heard the word groupies, we all had our favorite waitresses.

They were what you’d country groupies?

Nelson: More than that. They were our first critics and our best ones, or worst, as the case may have been. They would tell the truth. If I had a turkey of an act, it would hurt their audience and cut their tips. And if my performance was good, they’d be very grateful for it.

They were more critical than adoring?

Nelson: Oh, waitresses could be pretty adoring, too. But they had a sharp sense of what was going on in a club. They had to. That honky-tonk was like their office, or their queendom.

“A honky-tonk is my queendom.” Sounds like a good country song.

Nelson: There are times, especially the good times, when almost everything sounds like a good country song.