John Lennon first met Yoko Ono at a London art gallery in 1967. At that time, he was in the heyday of his recording career as a Beatle and was recognized the world over as one of the greatest performers and writers of popular music.

Yoko & John — An Exclusive Long-Lost Conversation

In those days, the name Yoko Ono meant little outside the New York art world. She was from a conservative Japanese family who moved to New York when she was 19. She studied at Sarah Lawrence, dropped out, and married a Japanese musician, then divorced him to marry American filmmaker Tony Cox, by whom she had a daughter.

Yoko was a serious artist, but relatively unknown until John Lennon entered that gallery. John walked over to a ladder, climbed it, picked up a magnifying glass, and read some tiny lettering on a canvas. It said “Yes.” John then asked to meet the artist.

Right away he found her fascinating. “As she was talking to me I would get high,” he told me, “and the discussion would get to such a level that I would be going higher and higher.” Within a matter of months John and Yoko moved in together. From then on the rest of the Beatles — and the whole world — would have to contend with the couple’s togetherness, as John and Yoko embarked on a series of exhibitionist events.

John and Yoko had been together four years when they gave us this interview. It took place at the St. Regis Hotel in New York in 1971. My coauthor, Robert Schonfeld, and I spent nearly three months setting it up, and ironically, when it was done we never published it. The reason was: We were writing a book, Apple to the Core, about the Beatles’ breakup. By the time we were granted this interview, the book was nearly written, and we used the material from it as background. The interview remained, until now, on a closet shelf.

At the time of our writing, the Beatles were in ruins. They were fighting among themselves, and they were no longer recording together. Many people attributed this to the influence of Yoko, on the one hand, and Linda Eastman, Paul McCartney’s wife, on the other. The Beatles’ business ventures had proved disastrous. Brian Epstein, their manager, was dead from an overdose of sleeping pills, and nobody was around to make sure the center held. After years of touring, and one successful album after another, their purportedly fabulous wealth was but a fraction of what the public supposed it to be. They were still rich by any standard, but they had lost control of their Northern Songs copyrights to Sir Lew Grade, chairman of ATV, a British entertainment conglomerate, after a long take-over battle. Their Apple venture had turned into a nightmare from which John finally emerged screaming “Help!” — a cry that was heeded by Allen Klein, who was soon to manage John, George, and Ringo.

The rift between John and Paul was huge. It took on every aspect of a celebrity divorce. Paul went into court seeking to dissolve the Beatles’ partnership, and John reacted to this by hanging out all the dirty linen. Typically, Paul did his best to smooth his feathers and look the other way. He had wanted his in-laws, the Eastmans, to handle the Beatles’ business, but to John the Eastmans were anathema. He saw them as the dreaded “men in suits,” whose posture was “We’re here to help you,” but who would really take control. On the other hand, he was drawn to Klein, the man the establishment didn’t trust.

Had Brian Epstein lived, it is conceivable that he might have been able to resolve the differences between John and Paul. The Beatles might have continued to record together. But who knows? The White Album is testament to their growing need to write and record separately, and as John said in this interview, he and Paul wrote separately far more than the public imagined.

When we turned up at the St. Regis for our first interview, John and Yoko were still in bed. It was early afternoon, and there was a flurry of activity in the adjacent suite of rooms. May Pang was much in evidence, bustling about, her long black hair swirling around her. (This was a year or two before her affair with John.) She told us that our interview would have to be interrupted by a fitting for Yoko, which turned out to be to our advantage, because in Yoko’s absence John was prepared to go back into the past and talk about Hamburg and the role of Brian Epstein.

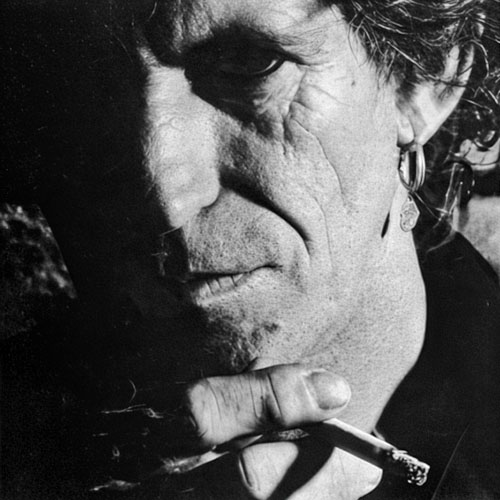

We were served tea on a silver tray. John chain-smoked Gauloises, and the interview proceeded. It was obvious from the start that he was still angry at Paul, but when I played the tapes later, I noticed he did not say anything negative about Paul’s music. He attacked Paul for being bossy, arrogant, chauvinistic, etc., but in the next breath he would be telling us about Hamburg, and about Paul having to be onstage for an hour and a half playing “What’d I Say,” and you could hear the affection in his voice.

I have listened to these tapes many times, and I have always been struck by the contradictions within John Lennon. He tended to see the world in terms of black and white, and people were either on his good list or his hit list, and often subject to being switched from one to the other, according to which way the conversation turned. He was always out-spoken, yet the charm of John’s outspokenness was not only his way with words, but also the fact that he was as critical and candid about himself as others. In the end it was this that made him endearing. He bared his soul about everything — his insecurities, his mistakes — and when he did so, even when he appeared ridiculous, he was a breath of fresh air in the entertainment world.

John said in this interview: “It had to take that special combination of Paul, John, George, and Ringo to make the [music or] there may never have been a Beatles. John was always the one to take risks, and so many of the stylistic influences, musical and otherwise, were his. His voice was heard in song, in jest, in protest, about every aspect of the culture he influenced. He was widely heeded, and eminently quotable, and he lived life as it should be lived: to the fullest. And as the unlikely figure of Sir Lew Grade said, “Those songs in Northern [Songs] will live on forever” — and as the man who now profits from them, he should know.

One moment that I remember during the interview was when John and Yoko were leaning toward the microphone, each jostling the other to tell the story of how they met and fell in love. No one could have been in their presence for those minutes and not have been affected by it. It never seems to have occurred to Yoko’s detractors, nor to the legions who still wanted to see John “married” to Paul, that John Lennon, who was never easily satisfied, was hardly likely to stick with someone he didn’t deem good for himself.

Yoko is a strong-minded woman, but her art has only limited appeal, no matter how hard she hustles. There are some who say that she had a negative effect on John’s music, but this seems absurd: “Imagine” and “Across the Universe,” and several others, were written while with Yoko, and they are as good as any of the songs he wrote before he met her.

Neil Aspinall, the Beatles’ longtime friend, said, “The Beatles’ world was an unreal world, a war zone.” It surely was. In a way I think Yoko brought John home. He found comfort, love, and understanding with her; he had a son by her and devoted himself to his child. I have no doubt he was a much happier man in 1980 than he was in 1967 when he walked into that London art gallery. — Peter McCabe

Interview

Let’s talk about the Beatles’ breakup, and the falling out between you and Paul. A lot of people think it had to do with the women in your lives. Is that why the Beatles split up?

John: Not really. The split was over who would manage us — Allen Klein or the Eastmans — and nothing else really, although the split had been coming from Pepper onward.

Why, specifically?

John: Paul was always upset about The White Album. He never liked it because on that one I did my music, he did his, and George did his. He didn’t like George having so many tracks. He wanted it to be more a group thing, which really means more Paul. He never liked that album, but I always preferred it to all the other albums, including Pepper, because I thought the music was better. The Pepper myth is bigger, but the music on The White Album is far superior, I think.

Is that your favorite of all the Beatles’ albums?

John: Yeah, because I wrote a lot of good shit on that. I like all the stuff I did on that. And the other stuff as well. I like the whole album. But if you’re talking about the split, the split was over Allen and Eastman.

You didn’t like Lee Eastman (Linda’s father) nor John (Linda’s brother). And the Eastmans didn’t like Allen Klein…

John: The Eastmans hated Allen from way back. They’re from the class of family … like all classes, I suppose, they vote like Daddy does. They’re the kind of kids who just think what their fathers told them.

But for a while didn’t you get along with Linda?

John: We all got along well with Linda.

When did you first meet her?

John: The first time was after that Apple press conference in America. We were going back to the airport and she was in the car with us. I didn’t think she was particularly attractive. A bit too tweedy, you know? But she sat in the car and took photos and that was it. And the next minute she’s married him.

Yoko: There was a nice quality about her. As a woman she doesn’t come on like a coquettish bird, you know? She was all right, and we were on very good terms, until Allen came into the picture. And then she said, “Why the hell do you have to bring Allen into it?” She said very nasty things about Allen.

Yoko, you weren’t with John the first time he met her?

Yoko: No. The first time I met her was when she came to the EMI studio. And you know, when the Beatles are recording, there are very few people around, especially no women. So I was there, and the first thing she made clear to me — almost unnecessarily — was the fact that she was interested in Paul and not John, you know? She was sort of presupposing that I would be nervous. She just said, “Oh, I’m with Paul.” Something to that effect.

I think she was eager to be with me, and John, in the sense that Paul and John are close, so we should be close, too. And couple to couple, we were going to be good friends.

What was Paul’s attitude to you as things progressed?

Yoko: Paul began complaining that I was sitting too closely to them [the Beatles] when they were recording, and that I should be in the background.

John: Paul was always gently coming up to Yoko and saying, “Why don’t you keep in the background a bit more?” I didn’t know what was going on. It was going on behind my back.

So did that contribute to the split?

John: Well, Paul rang me up. He didn’t actually tell me he’d split, he said he was putting out an album. He said, “I’m now doing what you and Yoko were doing last year. I understand what you were doing.” So I said, “Good luck to yer.”

So, John, you and Paul were probably the greatest songwriting team in a generation, and you had this big falling-out. Were there always huge differences between you and Paul, or did you have a lot in common?

John: Well, Paul always wanted the home life, you see. He liked it with Daddy and the brother … and obviously he missed his mother. And his dad was the whole thing. Just simple things: He wouldn’t go against his dad and wear drainpipe trousers. And his dad was always trying to get me out of the group behind me back, I found out later. He’d say to George, “Why don’t you get rid of John? He’s just a lot of trouble. Cut your hair and wear baggy trousers” — like I was the bad influence, because I was the eldest.

So Paul was like that. And I was always saying, “Face up to your dad, tell him to fuck off. He can’t hit you. You can kill him [laughs], he’s an old man.” I used to say, “Don’t take that shit.” But Paul would always give in to his dad. His dad told him to get a job, he dropped the group and started working on the fucking lorries, saying, “I need a steady career.” We couldn’t believe it. Once he rang up and said he’d got this job and couldn’t come to the group. So I told him on the phone, “Either come or you’re out.” So then he had to make a decision between his dad and me, and in the end he chose me. But it was a long trip.

So do you think with Linda he’s found what he wanted?

John: I guess so. I guess so. I just don’t understand …. I never knew what he wanted in a woman because I never knew what I wanted. I knew I wanted something intelligent or something arty, but you don’t really know what you want until you find it. So anyway, I was very surprised with Linda. I wouldn’t have been surprised if he’d married Jane [Asher], because it had been going on a long time and they went through a whole ordinary love scene. But with Linda it was just like — boom! She was in and that was the end of it.

So if the falling-out was essentially with Paul, what made you decide not to do the Bangladesh concert with George?

John: I told George about a week before it that I wouldn’t be doing it. I just didn’t feel like it. I just didn’t want to be fucking rehearsing and doing a big show-biz trip. We were in the Virgin Islands, and I certainly wasn’t going to be rehearsing in New York, then going back to the Virgin Islands, then coming back up to New York and singing. And anyway, they couldn’t have got any more people in, if I’d been there or not. I get enough money off records, and I don’t feel like doing two shows a night.

Do you have any regrets about not doing it?

John: Well, at first I thought, “Oh, I wish I’d been there.” You know, with Dylan and Leon … they needed a rocker. Everybody was telling me: “You should have been there, John.” But I’m glad I didn’t do it in a way because I didn’t want to go on as “the Beatles.” And with George and Ringo there it would have had that connotation of Beatles — now let’s hear Ringo sing “It Don’t Come Easy.” That’s why I left it all. I don’t want to play “My Sweet Lord.” I’d as soon go out and do exactly what I want.

John, you said you “get enough off records,” but you used to say you weren’t as rich as people thought you were. Are you rich enough finally?

John: I do have money for the first time really. I do feel slightly secure about it, secure enough to say I’ll go on the road for free. The reason I got rich is because I’m so insecure. I couldn’t give it all away, even in my most holy, Christian, God-fearing, Hare Krishna period. I need it because I’m so insecure. Yoko doesn’t need it; she always had it. I have to have it. I’m not secure enough to give it all up because I need it to protect me from whatever I’m frightened of.

Yoko: He’s very vulnerable.

John: But now I think Klein’s made me secure enough. It’s his fault that I’ll go out for free.

You mean tour for free?

John: Well, I thought, I can’t really go on the road and take a lot more money. What am I going to do with it? I’ve got all the fucking bread I need. If I go broke, well, I’d go on the road for money then. But now I just couldn’t face saying, “Well, I cost a million when I sing.”

Yoko: It’s criminal.

John: It’s bullshit, because I want to sing. So I’m going out on the road because I want to this time. I want to do something political and radicalize people, and all that jazz. I feel like going out with Yoko and taking a really far-out show on the road, a mobile, political rock-and-roll show….

Yoko: With clowns as well.

John: You know what I was thinking? When Paul’s out on the road, I’d like to be playing in the same town for free, next door! And he’s charging about a million. That would be funny.

Yoko: Our position is, I come from the East, he comes from the West — a meeting of East and West, and all that. And to communicate with people is almost a responsibility. We actually are living proof of East and West getting along together. High water falls low, you know. And if our cup is full, it’s going to flow. It’s natural for us to give because we have a lot. If we don’t give it’s criminal, in the sense that it’s going against the law of nature. In order to go against the law of nature, you have to use tremendous energy.

Let’s move on to Allen Klein. He has a reputation as a tough wheeler-dealer in the music business. What made you decide to have him as your manager?

John: Well, Allen’s human, whereas Eastman and all them other people are automatons. And one of the early things that impressed me about Allen — and obviously it was a kind of flattery as well — was that he really knew which stuff I’d written. Not many people knew which was my song and which was Paul’s, but he’d say, “Well, McCartney didn’t write that line, did he?” I thought, anybody who knows me that well, just by listening to records, is pretty perceptive. I’m not the easiest guy to read, although I’m fairly naive and open in some ways, and I can be conned easily. But in other ways I’m quite complicated, and it’s not easy to get through all the defenses and see what I’m like. Also, Allen knew to come to me and not to go to Paul. Whereas somebody like Lew Grade or Eastman would have gone to Paul.

“I was always telling Paul, ‘Face up to your dad. Tell him to fuck off. He can’t hit you. You can kill him, he’s an old man.’”

Did Klein hope to get Paul back into the group?

John: (laughs) He came up with this plan. He said, “Just ring Paul and say, ‘We’re recording next Friday. Are you coming?’” So it nearly happened. Then Paul would have forfeited his right to split by joining us again. But Paul would never, never do it, for anything. And now I would never do it.

There was a lot of negative publicity about Klein. Didn’t that bother you?

John: Well, he’s a businessman. He’s probably cut many people’s throats. So have I. I made it, too. I mean, I can’t remember anybody I literally cut, but I’ve certainly trod on a few feet on the way up. And I’m sure that Allen did also.

How does Klein compare with Brian Epstein, as a manager?

John: Well, Brian couldn’t delegate, and neither can Allen. But I understand that. When I try and delegate it never gets done properly. Like with my albums and Yoko’s, each time I have to go through the same process: get the printing size right. I want it clear and simple. I have to go through the same jazz all the time. It’s never a lesson learned.

Let’s get back to something we were talking about earlier. The attitude of the other Beatles toward Yoko.

John: They don’t listen to women. Women are chicks to them.

What about George?

John: George always has a point of view about that wide [he holds his hands close together], you know? You can’t tell him anything.

Yoko: George is sophisticated, fashion-wise ….

John: He’s very trendy, has just the right clothes on, and all of that.

Yoko: But not sophisticated intellectually.

John: No, he’s very narrow-minded. One time in the Apple office I was saying something, and he said, “I’m as intelligent as you, you know.” This must have been resentment. Of course, he’s got an inferiority complex from working with Paul and me.

Yoko: In the case of Paul, though, it’s not that he’s not sophisticated. I’m sure that he is sophisticated. He’s aware, but he just doesn’t want to know.

So the others and the rest of the Beatie entourage, they were hostile to you?

Yoko: Well, I’m a real female lib, and the rest of the Beatles, aside from Ringo, who’s been very good, showed their true colors by completely ignoring me in public. Can you imagine it? I’m a woman, who supposedly came into their world …. To that extent, I had some influence on them. But they would never speak of me in public, never mention anything, in any article. And presumably reporters would ask them about me.

John: Even now in Apple, they sometimes miss Yoko’s records off a listing. There’s always something wrong — one of Yoko’s albums will be missing, or they’ll get it mixed up.

Yoko: I feel I want to be just to them. This is a thing I have because of my upbringing. I want to be a good girl. But they’re saying that my art is not as important as John’s art, right? That’s an outright insult. You don’t say that to anybody, even if you think it, right? That’s a male chauvinist statement.

John: It was always presumed that she must behave like Cyn and Patti and all them — just go into the background. And Paul and Derek [Taylor] and all of them were in collusion to kill Two Virgins. I was told by people that they had meetings where Paul said, “Let’s kill it.” And I gave them chance after fucking chance. I said, “Look, they’ll get used to it.” And they went on and on and on, just being abusive and trying to pretend she didn’t exist, and that she didn’t have any art, that she had a lucky break meeting me, and that she should be on her fucking knees and not interfere with them. But she’d stand up to them and say, “That’s dumb! What the hell do you want him to do that for?” She’d start telling them, as an equal, what she thought about any given situation, and they couldn’t take it.

Yoko: For instance, I told Paul, I said, “Paul, please understand this, if Linda gets a prize in filmmaking or photography — because that’s her bit-we’re all going to be proud. It’s going to be good for the Beatles, good for all of us. And I would be proud of it, because she’s one of the family.” I said, “I was an artist, I was working very hard until I met John. Please let me work. And obviously, you know it’s very difficult for me to work now, the way it is.” At one point I said, “Listen, I’m so much in love with John. Sometimes, because I’m so involved in his work, I feel like forgetting about mine.” And he said, “Right, that’s good. You feel happy with that. That’s women’s happiness.” He believed that. And he encouraged me to forget about my work.

John, what did you think of Yoko’s work when you first saw it?

John: Well, her gallery show was a bit of an eye-opener. I wasn’t sure what it was all about. I knew there was some sort of con game going on. She calls herself a concept artist, but with the “cept” off, it’s “con” artist. I saw that side of it, and that was interesting. And then we met.

Was it love at first sight?

John: Well, I always had this dream of meeting an artist woman I would fall in love with. Even from art school. And when we met and were talking, I just realized that she knew everything I knew — and more probably. And it was coming out of a woman’s head. It just sort of bowled me over. It was like finding gold or something. To have exactly the same relationship with any male you’d ever had, but also you could go to bed with it, and it could stroke your head when you felt tired or sick or depressed. Could also be Mother. And if the intellect is there … well, it’s just like winning the pools. So that’s why when people ask me for a precis of my story, I put “born, lived, met Yoko,” because that’s what it’s been about.

As she was talking to me I would get high, and the discussion would get to such a level that I would be going higher and higher. And when she’d leave, I’d go back into this sort of suburbia. Then I’d meet her again and my head would go off like I was on an acid trip. I’d be going over what she’d said and it was incredible, some of the ideas and the way she was saying them. And then once I got a sniff of it, I was hooked. Then I couldn’t leave her alone. We couldn’t be apart for a minute from then on.

Yoko: He has this nature, and I’m thankful for it. Most men are so narrow-minded. Somebody once told me: “You don’t make small talk, and that’s why men hate you.” I mean, I have so many male enemies who try to stifle me. What the hell.

John: I did the same, of course. I found myself being a chauvinist pig with her. Then I started thinking, “Well, if I said that to Paul, or asked Paul to do that, or George, or Ringo, they’d tell me to fuck off.” And then you realize: You just have this attitude to women, that is just insane! It’s just beyond belief, the way we’re brought up to think of women. And I had to keep saying, “Well, would I tell a guy to do that? Would I say that to a guy? Would a guy take that?” Then I started getting nervous. I thought, “Fuck, I better treat her right or she’s going to go. No friend’s going to stick around for this treatment.”

Did you know anything about rock music, Yoko, when you first met John?

Yoko: I didn’t know anything about rock, or anything like it. I thought of rock songs as something a bit lower than poetry. It was like reading poetry that had a definite kind of rhythm to it.

“Yoko calls herself a concept artist, but with the “cept” off, it’s “con” artist. I saw that side of it… and then we met.”

John: She used to say, “Why are you doing that same beat all the time?” I used to get very irritated.

What were your feelings about art and the art world at that time?

John: Well, I went to art school and I thought that was the art world, virtually. And they’re all such pretentious hypocrites. There was no artist I admired, except for maybe Dali or someone from the past. And when I read the art reviews… I couldn’t understand why I wasn’t being reviewed for my art, because I always felt like an artist.

So I went to her show. I was thinking, “Fucking artist shit. It’s all bullshit.” But then there were so many good jokes in it, real good eye-openers.

Yoko: That’s another thing, most artists don’t have a sense of humor.

John: And there was a sense of humor in her work, you know? It was funny. Her work really made me laugh, some of it. So that’s when I got interested in art again, just through her work.

Yoko: All the men I met, I felt they were more pretentious than me, hypocritical, narrower than me, and not genuine. And I’m talented. Because I can compose, I can paint, I can be in many fields. Most men that I met were bragging about their professionalism in one field.

John: They get one idea and flog it to death, and become famous on one idea.

Yoko: And fucking conservative, you know? And they talk about women not having a sense of humor. I used to despise every man that I met. I was thinking, “There’s something wrong with me, because everybody hated me for it.” And then I met this man, and for the first time I got the fright of my life because here was a man who was just as genuine, maybe more genuine, than me. He’s very genuine. And he can do anything that I can do, which is very unusual. And I really got surprised. And that happened at the first meeting.

John: It took me a long time to get used to it. Any woman I could shout down. Most of my arguments used to be a question of who could shout the loudest. Normally, I could win, whether I was right or wrong, especially if the argument was with a woman — they’d just give in. But she didn’t. She’d go on and on and on, until I understood it. Then I had to treat her with respect.

Yoko, did you have any idea of what the Beatles’ life had been like, on the tours, for example?

John: She was really shocked. I thought the art world was loose, you know? And when I started telling her about what our life was like, she couldn’t believe it.

Yoko: I came from a different generation. I mean, my friends didn’t want me to know they smoked pot, you know? So I thought, “Oh, he’s an artist. He’s probably had two or three affairs.” Then I heard the whole story and I thought, “My God!”

John: She was just like this silly Eastern nun wandering about, thinking it was all spiritual.

Yoko: He once said to me, “Well, were you a groupie in the art world?” I said, “What’s a groupie?”

John: So I said, “Just tell me. I don’t want to go ‘round, and fucking Picasso or somebody comes up and says, ‘Yes, I’ve had her.’”

Yoko: And I really didn’t know the word “groupie.”

John: So anyway, I’d been dying to tell her about the “raving” on tour. I just wanted her to know what a scene it was. I thought it was silly not to say it. And of course the people with us were living like fucking emperors when we were locked in our rooms. That’s why they cling so much to the past.

Talking of your entourage, do you resent it that so many people take credit for their contributions to the Beatles?

John: Well, there was an article on George Martin in Melody Maker — he’s telling all these stories. He says, well, I showed them how to play feedback, or put loops together, or some arbitrary little technical thing … like showing you how to lay a page out, you know? Where is the great talent of George Martin and Derek Taylor, and the legacy of Brian Epstein? Where is their talent?

Yoko: It’s like my ex-husband saying that he sacrificed his talent for me, or something.

John: Well, I never had anything against George Martin. I just didn’t like all the rumors that he actually was the brains behind the Beatles. I can’t stand that.

Let’s talk about Brian Epstein, your first manager. What did you think of him?

John: I liked Brian. I had a very close relationship with him for years, like I have with Allen, because I’m not going to have some stranger running the scene, that’s all. I was close with Brian, as close as you can get with somebody who lives sort of the fag life, and you don’t really know what they’re doing on the side. But in the group I was closest to him. He had great qualities and he was good fun.

He was a theatrical man rather than a businessman, and with us he was a bit like that. He literally fucking cleaned us up. And there were great fights between him and me, over years and years, of me not wanting to dress up. He and Paul had some kind of collusion … to keep me straight. Because I kept spoiling the image, like the time I beat up a guy at Paul’s twenty-first [birthday]. I nearly killed him. Because he insinuated that me and Brian had had an affair in Spain. I was out of me mind.

What I think about the Beatles is that even if there had been Paul and John and two other people, we’d never have been the Beatles. It had to take that combination of Paul, John, George, and Ringo to make the Beatles. There’s no such thing as, “Well, John and Paul wrote all the songs, therefore they contributed more,” because if it hadn’t been us we would have got songs from somewhere else. And Brian contributed as much as us in the early days, although we were the talent and he was the hustler.

So after Brian died you made Magical Mystery Tour. You said Paul was acting as if he were going to take charge of everything?

John: Well, I still felt, every now and then, that Brian would come in and say, “It’s time to record,” or “Time to do this.” And then Paul started doing that — “Now we’re going to make a movie,” or “Now we’re going to make a record.” And he assumed that if he didn’t call us, nobody would ever make a record. Well, it’s since shown that we managed quite well to make records on time. I don’t have any schedule. I just think, “Now I’ll make it.” But in those days, Paul would say that now he felt like it. And suddenly I’d have to whip out 20 songs. He’d come in with about 20 good songs and say, “We’re recording.” And I had to suddenly write a fucking stack of songs. Pepper was like that. Magical Mystery Tour was another. So I hastily did my bits for it. And we went out on the road. And Paul did the thing he did for his album — the big-timer, auditioning directors.

Let’s go back for a minute and talk about all the early influences on the Beatles. What would you say had the greatest effect on the group? Was it Liverpool? The Cavern? Hamburg? Did Hamburg really improve the playing?

John: Oh, amazingly. Because before that we’d only been playing bits and pieces, but in Hamburg we had to play for hours and hours on end. Every song lasted 20 minutes and had 20 solos in it. We’d be playing eight or ten hours a night. And that’s what improved the playing. Also, the Germans like heavy rock, so you have to keep rocking all the time, and that’s how we got stomping. That’s how it developed. That made the sound. Because we developed a sound by playing hours and hours and hours together.

You all must have found yourself playing in some unbelievably bad conditions.

John: Yeah, but it was still rather thrilling when you went onstage. A little frightening because it wasn’t a dance hall, and all these people were sitting down, expecting something. And then they would tell us to “mak show” (make a show). After the first night they said, “You were terrible, you have to make a show — ‘mak show.’” So I put me guitar down and I did Gene Vincent all night. You know -banging and lying on the floor and throwing the mike about and pretending I had a bad leg. They’re all doing it now — lying on the floor and banging the guitar and kicking things and just doing all that jazz.

Then they moved us to another club, which was larger and where they danced. Paul would be doing “What’d I Say” for an hour and a half. And these gangsters would come in — the local Mafia. They’d send a crate of champagne onstage, this imitation German champagne, and we had to drink it or they’d kill us. They’d say, “Drink it and then do ‘What’d I Say.’” We’d have to do this show, whatever time of night. If they came in at five in the morning and we’d been playing seven hours, they’d give us a crate of champagne and we were supposed to carry on. We’d get pills off the waiters then, to keep awake. That’s how all that started.

I used to be so pissed [drunk]… I’d be lying on the floor behind the piano, drunk, while the rest of the group was playing. I’d just be onstage fast asleep. Some shows, I went on just in me underpants. I’d go on in underpants with a toilet seat round me neck, and all sorts of gear on. Out of me fucking mind!

When did you get into acid? Did Paul time his LSD announcement to coincide with the release of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band?

John: No. We’d had acid on Revolver. Everybody is under this illusion. Even George Martin saying, “Oh, yeah, Pepper was their acid album.” But we’d had acid, including Paul, by the time Revolver was finished.

So why did he make that big announcement?

John: Because the press had cornered him. I don’t know how they found out he was taking it. But that was a year after we’d all taken it. Rubber Soul was our pot album; and Revolver was acid. I mean, we weren’t all stoned making Rubber Soul because in those days we couldn’t work on pot. We never recorded under acid or anything like that. It’s like saying, “Did Dylan Thomas write Under Milk Wood on beer?” What the fuck does that have to do with it? The beer is to prevent the rest of the world from crowding in on him. The drugs are to prevent the rest of the world from crowding in on you. They don’t make you write better. I never wrote any better stuff because I was on acid or not on acid.

“Even if there had been Paul and John and two other people, we’d never have been the Beatles. It had to be that combination of Paul, John, George, and Ringo.”

Did the fact that Sergeant Pepper inspired so many people to try LSD surprise you?

John: Well, I never felt that Haight-Ashbury was a direct result. It always seemed to me that all sorts of things were happening at once. The acid thing in America was going on for a long time before Pepper. Leary was going around saying, “Take it, take it, take it.” We followed his instruction. I did it just like he said in the Book of the Dead, and then I wrote “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which is on Revolver, and which was almost the first acid song — “lay down all thought, surrender to the void” — and all that shit.

Do you remember if Paul’s statement on acid came out after Sergeant Pepper?

Just as it was released.

John: I see. He always times his big announcements right on the letter, doesn’t he? Like leaving the Beatles. Maybe it’s instinctive. It probably is. He’s got the timing for it. Anyway, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” is not about LSD. And “Henry the Horse” is not about smack on Sergeant Pepper, because I’d never even seen it when we made Sergeant Pepper. But those kinds of stories evolved from it — people thought if you listened to it backwards it said “Paul is dead.” All that shit is just gobbledygook.

Still, many who got into acid might never have followed Timothy Leary but did follow the Beatles.

John: Well, blame it on Dylan. He turned us on to pot.

Having written so much with Paul, do you think it’s possible for there to be some type of settlement, outside of business?

John: Well, there’s no way for it to be settled “outside business,” because it all gets down to who owns a bit of what. It’s a house we own together, and there’s no way of settling it, unless we all decide to live in it together. It has to be sold.

Have you missed writing songs with him?

John: No, I haven’t. I wrote alone in the early days. We used to write separately. He used to write songs before I even started writing songs. I think he did. And we’d written separately for years. In Help I wrote “Help.” I wrote “A Hard Day’s Night.” He wrote “Yesterday.” They’d been separate for years.

In the early days we wrote together for fun, and later on for convenience, to get so many numbers out for an album. But our best songs were always written alone. And things like “Day in the Life” was just my song and his song stuck together. I mean we used to sit down and finish off each other’s songs. You know, you could have three quarters of a song finished and we’d just sit together, bring ten songs each, and finish off the tail ends, and put middle eights in ones that you couldn’t be bothered fixing, because they weren’t all that good anyway.

We usually got together on songs that were less interesting. Now and then we’d write together from scratch. Things like “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” — things like that were done like that. But we’d been working apart ever since we were working together. It was only news to the public that a lot of Lennon-McCartney songs weren’t Lennon-McCartney. That was something we’d agreed on years ago.

Do you think it was a mistake in retrospect to have named everything Lennon-McCartney?

John: No, I don’t, because it worked very well when it was useful. Then it was useful, so it was quite good fun. I’ve nothing against it.

If you got — I don’t know what the right phrase is — “back together” now, what would the nature of it be?

John: Well, it’s like saying, if you were back in your mother’s womb … I don’t fucking know. What can I answer? It will never happen, so there’s no use contemplating it. Even if I became friends with Paul again, I’d never write with him again. There’s no point. I write with Yoko because she’s in the same room with me.

Yoko: And we’re living together.

John: And we’re living together. So it’s natural. I was living with Paul then, so I wrote with him. It’s whoever you’re living with. He writes with Linda. He’s living with her. It’s just natural.

Should you be interested, you can still find used copies of Apple to the Core floating around. Consider it a retro adventure to read a book printed on actual paper. It’ll be fun. … Much of the philanthropic work that came from Yoko Ono and her interaction with John still exists today under the compelling name Imagine Peace. We often get a bad name, identification most-often used as a “head in the clouds, unrealistic, idealist” insult, but you still have to respect the tree-hugger. Trees are cool.