Maoism

The Time is Mao

Wild-eyed youths tearing down statues. Self-righteous twenty-somethings raging against older people who dare to think differently to them. Prim, unforgiving university students stalking their campuses in search of offensive books and offensive speakers so they can point a bony finger of judgment at them while yelling: “Not allowed!”

That was Mao’s China in the late 1960s. The Cultural Revolution was in full flow. Statues of Buddha and other “offensive” figures were yanked down and set on fire by hotheaded arrogant Red Guards. Wrong-thinkers were hounded out of public life. Books were thumbed for inappropriate ideas, and if they contained any, they were banned.

Sound familiar? It should. In the weeks since the horrific killing of George Floyd by cops in Minneapolis, a culture of neo-Maoism has gripped the throat of the USA and other Western nations. A supremely intolerant war has been launched against history, against monuments, against incorrect thought.

This is American Maoism.

The speed with which understandable anger about the killing of George Floyd morphed into all-out culture war against history and liberty has been staggering. One day people were marching in the streets to condemn police brutality, the next, mobs were tearing down a statue of George Washington in Portland, Oregon, and whooping and cheering as they kicked it in the head and tried to set it on fire.

George Washington. The revolutionary and first president of the United States. A man who helped birth a modern republic built on the ideals of liberty and trade and who, in the process, changed the world forever. Even he is not safe from the wild-eyed fury and fists and kicks of the Woke Guards of American Maoism.

Nothing is. We’ve seen classic comedy shows like Little Britain being shoved down the memory hole because they are apparently offensive. Trigger warnings are being added to old movies, from Gone with the Wind to Aliens, to let people know they contain “problematic” ideas. People have been sacked from their jobs for criticizing the Black Lives Matter movement. In the U.K., a radio presenter was suspended after he questioned the idea of “white privilege.”

Under American Maoism, no dissent is tolerated; no criticism of the new orthodoxies of political correctness will be entertained. Instead, you must dutifully, unquestioningly “take the knee”— that is, bow down, like a supplicant, to confirm that you have embraced the gospel truth of identity politics. Woe betide anyone who refuses to bend his knee to American Maoism. The British Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab, was shamed and hounded for days when he said, quite rightly, that taking the knee looks like “a symbol of subordination.”

American Maoism even had its own little corrupt pseudo-state for a while: CHAZ, the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle. This ridiculous entity confirmed how regressive and dangerous the woke worldview has become. It had a blacks-only public space, reintroducing racial segregation into the U.S. Its inhabitants rained fury upon any visitor who did not subscribe to the CHAZ worldview, especially if that visitor was wearing a MAGA hat. It was essentially a massive safe space for adult snowflakes.

What has been most striking is the glee with which big corporations and even sections of the political establishment have lined up behind American Maoism. Big business sings the praises of BLM. Corporations are buying thousands of copies of deranged books like White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo to re-educate their workforce. Leading American politicians have feverishly tweeted pics of themselves “taking the knee.”

The involvement of the establishment in all this is revealing. It shows that what we’re really witnessing right now is a revolt of the elites. This isn’t a youthful rebellion against the powers-that-be. It’s a bunch of upper-middle-class TikTok plastic radicals, effete Antifa assholes, corporate suits, and leftish members of the political elite expressing their lingering fury with the way politics has been going since the votes for Trump and Brexit in 2016.

Don’t be fooled by the radical pretensions of the Woke Guards. Their real target is the populist surge of recent years; their blind fury is directed at voters, especially working-class ones. This is a nasty elitist putsch posing as a people’s uprising.

To add some perspective to this guest editorial from the Australian edition of Penthouse, take a look at how we used to view America — 40 years ago in this same publication. And then take a look at where we want to avoid as a destination.

UFC: The Fight of the Century

Conor McGregor was talking about himself and the Irish nation he represents after an emotional victory in the Octagon back in 2014. But he could well have been talking about the sport he competes in.

In less than three decades, the UFC has gone from being perceived as a bloodbath freak show, to a highly popular sport with a regular global TV audience. Of the 10 highest Pay Per View audiences of all time, there are already three UFC contests – two involving McGregor. While boxing still leads the way, it is worth noting that three of those ten are Tyson fights from back in the day. The recent Khabib versus McGregor fight is ranked at third of all time, with only Mayweather versus Pacquiao ahead of it as a pure boxing title fight.

At number two is Mayweather and McGregor, when the two richest fighters in their respective sports, met on Mayweather’s terms. If McGregor was to rematch with either Mayweather or Khabib, then a new record might be set.

Conor has taken UFC to a new level. But Dana White is the man who gave him the platform and has set up the sport for success.

It’s as if Dana brought a communist ethic to boxing when he reimagined UFC. No more maverick promoters, individual fiefdoms, breakaway organisations and economic divide. Just one dictator, largely working for the greater good – as well as himself.

Yes, you can still make far more money as a top boxer (heavyweights Fury, Joshua and Wilder all earned as much as McGregor, if not more in 2019, with far less fanfare). But the fighters on the undercards of UFC make more than the journeyman boxers.

There is also only one organisation in the UFC, one main promoter and the events are organised and regular. Boxing tends to feel sporadic and random – big when a fight is being promoted, but you’re never sure when that’s happening next.

Dana just decides to get it on for the good of the sport and, of course, himself and his fighters. Hearns, Warren, Haymon, Arum, Don King et al, shadow box in business for their own ends.

Boxing is also more confusing than ever to the average punter when it comes to who is the best.

In boxing there is the WBC, WBO, WBA and IBF. Only dedicated boxing fans could tell you which is the most important. Throw in 17 weight divisions for the boxers and that’s a hell of a lot of world champions. In the prized middleweight division, there are currently four different titleholders.

Watching Fury beat Wilder for the heavyweight title was exciting, but he’s only got one of the belts. He needs to fight Anthony Joshua for a couple of the others. Again, the promoters will decide if and when that happens.

UFC has eight weight divisions and eight champions — nine if you count Justin Gaethje, who has Khabib’s lightweight belt on an interim basis. It’s regular and pragmatic. More of a democratic feel to it, despite Dana the Despot.

There are even famous women in UFC. Most sports fans have heard of Ronda Rousey but would struggle to name a female boxer. (Muhammed Ali’s daughter doesn’t count).

The only thing UFC truly lacks is a longer-term narrative, with drama and characters.

Boxing has a legacy — from Tyson to Marciano; the middleweights of the 80s (Hearns, Hagler, Leonard, Duran, De La Hoya). Characters like Don King. Legendary stories like the Rumble in the Jungle. Even fictional heroes in the form of Rocky and Creed.

That will come for UFC, though. In relative terms, it’s a baby. The man in the street knows McGregor. He might know Khabib (the ferocious Russian grappler, undefeated in 28 fights). But he probably couldn’t name Jon Jones or Georges St. Pierre unless he was a fan. Even Aussies might not know they have a world champ at Featherweight in the form of Alexander Volkanovski.

You can be sure though that UFC is coming for boxing though, quicker than the right-hand McGregor dropped Jose Aldo with.

“I’m the fucking future” said McGregor when he was still a fresh-faced Dubliner, fighting for a few quid. Again, he could have been talking about his sport, as much as himself.

Should you desire a bit more knowledge about Conner as a “Brand” then we shall help you consider this.

Christmas Cam Girls

Staying Home at Christmas with Cam Girls

These girls are lonely and have been looking to make new friends in the online world. In fact, gorgeous women from all over the world have been looking to make a special connection with someone for the holidays. It’s not as fun for these girls to open Christmas presents unless someone is there to see the sparkle in their eyes when they find exactly what they’re looking for … catch the drift?

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! Even though this year has taken a toll on most of us in ways more than one, it’s still the holiday season! Now that Christmas is here, it leaves us wondering if we can actually enjoy ourselves while we remain inside in quarantine. Clearly, the option to leave isn’t safe. We can’t travel, attend parties, see holiday shows, or find a hot chick at a bar who will give us a holly jolly night. The babes we want to see won’t be found outdoors this year…but instead from our computer screens.

There are plenty of other ways to celebrate Christmas on Camster. Browse the site for that beautiful girl who’s stuck in quarantine just like the rest of us. She’ll be looking for someone who will give her a Merry Christmas and she’ll do the same in return. Here are just a few things the two of you can do together: talk about holiday traditions you had growing up, drink hot cocoa together, listen to your favorite Christmas songs, or play a game…

But let’s remember that Camster girls are there to please in…other ways. It’s fun to play Christmas jingles with a beautiful girl, but it’s another to play them while she’s removing her bra. These ladies can give naughty cam shows this Christmas for all the viewing pleasure. All they need is someone to tell them what to do whether it’s titty play, dildo fun, dirty talk, or some raunchy Christmas roleplay! How often do we get the chance to play Mr. and Mrs. Claus? Or, she could play the lonely girl who’s home from college and can’t visit family so she spends Christmas with a handsome stranger who will keep her warm.

Whatever dirty thoughts come to mind, Camster.com has thousands of girls who want to perform in live sex chat this Christmas. After all, tis the season!

Here are five cam girls to check out for the holiday season:

“My mind is very open, so there is always room for a new fantasy, for a new desire…”

“A beautiful and sensual girl, who drives any man crazy, has a perfect body and delicious skin that calls to taste, that inspires desire and lust just by looking at her.”

“Beautiful girl, beautiful person. You have not discovered this site until you have chatted with her. You owe it to yourself to take her private.”

“Passion is the better word to describe what you can feel by seeing this Latina model. Full of elegance!”

“A great combination of little girl cute and porn star hot. When taken there, she goes wild.”

Get your private show this Christmas with thousands of cam girls on Camster.com!

And don’t forget to see all our Camster features.

Lola Montez: The Un-Victorian

When the good citizens of Ballarat, Australia, stopped in the street in February 1856 to watch a comely young woman beating seven kinds of hell out of Henry Seekamp, editor of the Ballarat Times, with a horsewhip, they probably thought it was just a fun new type of public entertainment.

This was the gold rush, after all, and excessive behavior was all the rage. It seemed quite in keeping with the free-spirited times that attractive women should assault journalists in the street. Few, if any, of those fun-loving Ballaratians would’ve known that the whip-wielding lady was one of the nineteenth century’s most extraordinary personalities, a woman who not only scandalized the masses with her provocative public performances, but showed the ability to influence world events with her even more provocative private ones. For this was Lola Montez, whose outsized ambition was exceeded only by her capacity to drive sane men mad.

Lola Montez was born Marie Dolores Eliza Rosanna Gilbert in County Slingo, Ireland, and with a name like that, it’s no surprise she decided to switch to something snappier. Her parents were, as they say, “good stock,” being an English army officer and the daughter of a Member of Parliament.

Having a good look at the respectable life, she quickly determined she’d follow the diametrically opposite path, eloping with Lieutenant Thomas James at the age of 16. Married life, however, was not for young Eliza, and she split from the lieutenant five years later, beginning her career as a Spanish dancer. As Eliza Gilbert wasn’t the most convincing name for a Spanish dancer, she assumed the moniker Lola Montez, birthing a legend.

Lola Montez was a big hit in Europe, although not always for her dancing. As she quickly discovered, her career fortunes trended upward the more amiable she was toward certain influential men. While living in Paris, she found critical acclaim, coincidentally at the same time as she was carrying on an affair with Alexandre Dujarrier, who was the owner of France’s most popular newspaper, as well as its most prominent theater critic.

It was not in Paris but in Munich that Lola made her biggest splash, after bewitching King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Upon their first meeting, Ludwig asked Lola whether her breasts were real, and Lola immediately provided him with incontrovertible proof. Ludwig was convinced: He must have this woman. In fact, not only must he have her, he must give her land, a fortune, and the title Countess of Landsfeld.

The newly ennobled Lola had such an effect on the lovestruck Ludwig that she actually exercised political influence, pushing his administration in an ever-more liberal direction and angering Bavaria’s religious conservatives. Ludwig’s infatuation with Lola did not end well. The public, sick of a king in thrall to the policy prescriptions of an Irish dancer, rose up in the revolution of 1848 and ousted him. Still, it could’ve been worse. Ludwig lived 20 years after being deposed; Dujarrier’s romance with Lola ended with him being shot dead in a duel.

After a brief stint in America, she decided, like so many thousands of others around the world, to head to the goldfields of Australia to see how rich the pickings were. Thus did the naïve colonials of Victoria discover the pleasures of Ms. Lola Montez.

She toured the regions, thrilling diggers from Bendigo to Castlemaine with her legendary “Spider Dance” (details are scant, but suffice to say when she got going you could’ve sworn she had eight legs).

But it was in Ballarat that her notoriety hit its peak, after the distinguished Mr. Seekamp published a scathing review of her dancing in the Times. Living the dream of millions of performers throughout the ages, Lola tracked Seekamp down at his local pub, dragged him into the street, and laid into him with the whip.

Unlike many other gentlemen of the time, Seekamp apparently didn’t enjoy being whipped by Lola Montez at all. In the colonies, this spectacular exercising of the right to reply would go down as Lola’s most indelible moment. But for the lady herself, it was just another day in one of the most remarkable lives anyone has ever lived.

Presuming you like the weird, check us out further.

Dommes Doom

The Failure Of On-screen Dommes

It’s not just the ill-fitting corset. It isn’t how utterly ludicrous it is that a mistress would pay someone 20 percent of her earnings to do … whatever it was that Mistress May (Zoe Levin) wanted Carter (Brendan Scannell) to do for her. (Clean? Do security? He just seemed to watch and reluctantly participate in sessions.) Even neophyte dommes know that there is an endless line of willing subs who’d not only do these tasks for free, but who might even pay to do them. It makes no fiscal sense!

What also makes Bonding bad is the way that May and Carter “other” the clients. The breaking of boundaries and consent. Domming is presented, as it so often is, as an untouchable goddess flicking a whip from a throne as money rains down gently around her.

After Bonding was released, it was no surprise my dungeon was inundated with calls from women who were shocked, shocked, when we described what being a pro domme is actually like. Bonding is the perfect example of why media needs to consult with people from a lived experience. And pay them for the consultation.

So, what about other media portrayals of Pro Dommes?

I think “The Woman” is a stupid domme name, but that’s what Irene Adler (Lara Pulver) works under in BBC’s 2010 reboot of Sherlock. This babe is fancy. I know of some “elite” mistresses and they are rarefied and cool, utterly unattainable, and I would aspire to be like them if I wasn’t quite so inescapably disheveled.

A deliciously tricky bitch, Ms. Adler is more interested in playing power games with Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) than doling out spankings. I can’t imagine her wrist-deep in some guy or getting piss on her stockings. Irene Adler would always be impeccably turned out, and I bet she’s the kind of mistress who never kicks her heels off mid-session.

In Secret Diary of a Call Girl, Belle de Jour (Billie Piper) isn’t really into fetish, but when her accountant/client requests it, she does what any smart escort should do and consults an expert. The dominatrix she takes lessons from is an older woman clad in head-to-toe leather with a devoted slave trailing behind. Mistress Sirona instructs Belle where to hit and how to tie a client up, but the control of a domme can’t really be taught. When Belle loses control and allows her anger to play a role in the punishment of her sub, she learns that there’s more to being a mistress than wielding the whip.

Crime drama The Sinner has within it an interesting portrayal of a professional dominatrix. Det. Harry Ambrose (Bill Pullman) is in a complex relationship with his Domme, Sharon (Meredith Holzman). Sharon is a glorious chunky babe, her blonde curls growing out an old dye job. In her first appearance, she’s wearing jeans and a T-shirt, but she commands Ambrose like she’s in head-to-toe leather, bullwhip unfurled. Sharon embodies the domme role so fully that the clothes aren’t necessary. She is in-fucking-charge. When Ambrose violates their agreement, she draws a firm boundary, and she doesn’t budge. A good dominatrix doesn’t need the fancy accoutrements of the dungeon, she only needs that intrinsic domme attitude. That, and a good sub.

The most nuanced domme on TV isn’t really on TV at all. Mercy Mistress, a web series produced by comedian Margaret Cho, is based on the memoir of Yin Quan, a Chinese-American pro-domme from New York. What makes Mercy Mistress so different from the usual narratives we see in media is the representation of the fullness of her experience. Mistress Yin (Poppy Liu) is a domme, yeah, but she’s also an activist, a queer woman, an immigrant, and an educator. The series avoids the usual trap of salaciousness, never dehumanizes the client for a joke, and gets into the guts of kink-for-pay: the aesthetics, the shame, the power, the dirt, and the gleam.

Mia Walsch is the author of “Money for Something” (Echo Publishing $29.99)

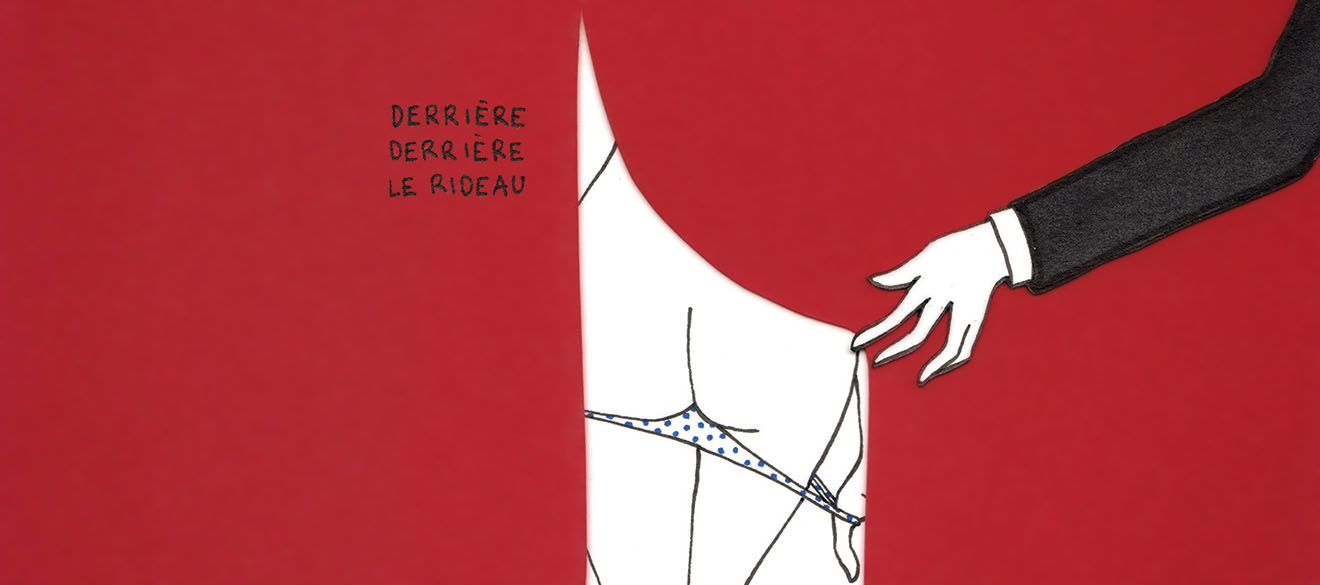

Petites Luxures

The Penthouse Interview

Pettites Luxures is an anonymous erotic artist bringing sexual subtlety to the masses through his sensual, simplistic line drawings. We spoke to the mystery man about how he went from being a commercial graphic designer to being an full-time erotic artist with 1.3 million Instagram followers.

Where did you grow up and where do you live now?

I grew up in Reims, a city in the east of France (where Champagne is made). I moved to Paris at 19 to study, but now I live in an old house in the countryside, about 30 miles from Paris. This is also where my studio is. I need to be calm and quiet to create, and it’s a good break from all the excitement of the art shows in the U.S., the book signings and the busy meetings in Paris.

How would you describe your art style?

My art is erotic, of course, minimalist, humorous, and also, I hope, poetic. That’s the drawing, but I try not to limit Petites Luxures to drawing only. I try to make sure all of my experiments are driven by this same romantic, erotic, humorous, poetic spirit.

How did you develop Petites Luxures?

All butts are different, but all are beautiful.

Initially I was, and still am, a graphic designer. I never considered graphic design as art, though. Petites Luxures was my first step into the art world. I started it back in 2014 in addition to my full-time job in art direction. At first it was just for fun, but when I found the online drawing community, I knew I wanted to build something strong within it. I knew I wanted to push Petites Luxures in a very artistic way.

What’s your favorite thing to draw?

I would say a butt, because it’s an important part in my drawings and because it’s very simple though very subtle to draw. Only three curves and you have a full volume in front of you. You slightly change one of these curves, and you change the whole orientation, the volume, the feeling of the body. All butts are different, but all are beautiful. You can never draw the same butt twice. I can draw a thousand butts and never get bored of it.

What materials do you use?

Mainly ink and paper. I used to be a very digital guy, using Photoshop every day for my work, but for Petites Luxures I needed to feel the drawing. For me, using a graphic tablet to make the final drawing would be cheating. I use a lot of pencils, pens, thin markers, fountain pens, India ink, brushes, and acrylic paint. I know I would be way more productive with a tablet, but I need my drawing to be an object I can hold in my hands, not just a file on my hard drive. The stroke, texture, and the imperfect curves are really important for me. My drawings would look terrible if made them with perfect vector lines in Illustrator! I also use my light table a lot to remake the same drawing several times from the first sketch until I find the right one. I also use a thesaurus when I need to find a good caption!

What inspires Petites Luxures to make art?

Well, a lot of things, but basically everything that is not erotic at first. A big part of my creative process is to find a way to eroticize something that is not erotic. Only representing something erotic would be very boring for me to do, and a lot of technically better artists would do it way better than me. I’m always writing down small things of my everyday life. It can be anything: a song, a place, something I ate, something I heard in the street. When I’m sitting at my desk, I read all these notes and try to find how to turn these into small funny erotic scenes.

Dozens of my drawings were removed by Instagram after people reported them.

Do you ever face censorship on social media? Yes. Dozens of my drawings were removed by Instagram after people reported them. That’s why I don’t use any hashtags now, so the people who come to my page know what they are searching for. When I decided to take a year off to run this project full-time, Instagram even disabled my whole account. I had the scare of my life as I’d been running the account for three years and had more than 500,000 followers.

But I appealed the decision, and happily, I recovered my account few hours later. I’m still afraid of censorship. Even more today because I do this for a living. I know that after the heated discussion about censorship of the artists Delacroix and Courbet, Facebook and Instagram are more permissive with handmade artworks like paintings and drawings. That is also one of the main reasons I try to build a strong work relationship in real life with art galleries, books, collaborations with brands, to make Petites Luxures live outside Instagram, too.

Tell us about your recent mini-show in Paris and the objects and artwork you had on display.

It was at the Woods Gallery, near Montmartre, which is a cool gallery run by a friend I met in art school a few years ago. He works with artists and talented craftspeople to create limited editions of cool objects. They also sell vintage designer furniture, and the artists customize some pieces of the collection. For this exhibition, I will work on customizing some chairs from the ’50s, and we will also produce a set of lino prints and screen prints.

Tell us about any upcoming Petites Luxures projects you have that you’re excited about.

This year, I have several cool upcoming projects! I’m currently working on a collaboration with a great French fashion brand that will be launched in a few months. My first book [Petites Luxures: Intimate Stories] has now been translated into English, Italian, Spanish and Flemish, and will soon be out in quite a lot of new countries, which is very exciting.

And I’m working with my publisher on my next book, which won’t be a sequel of the first one, but rather, something totally different. I’ve also got a few events, fairs, conventions and TV shows on the horizon, too.

INSTAGRAM: @petitesluxures

Chilling With The Iceman

The Iceman

It’s a few days after his birthday when I call Wim Hof, the legendary “Iceman” and extreme athlete known for his superhuman ability to withstand long-term exposure to sub-zero conditions. It’s the middle of coronavirus lockdown, but he tells me he was still able to celebrate turning 61 by spending a frosty 61 minutes in an ice bath. He shrugs it off and says he could have endured longer. Most people would struggle to do ten minutes in similar conditions.

Hof has an infectious personality, his wide-eyed enthusiasm for wellness and giddy verbiage only occasionally tempered by a reference to the hard science backing his claims. In other interviews, he’s been challenged for getting the facts wrong, and he explains that his children, who also help him run his business, are always having to remind him to stick to what can be proven — not stretch his claims too far, so as to avoid drawing criticism from the skeptic community. But with Hof, it seems he can’t quite help himself.

He does make a few mistakes on the science in our interview, and he certainly has a tendency to get carried away. But he is genuine — I get the definite impression he truly believes in making a positive impact on people’s lives through the Wim Hof Method. And while he may have scientific blind spots, there are plenty of studies to back up the benefits of the deep breathing techniques and cold exposure he has pioneered.

In your own words, what is the Wim Hof Method?

It began as a soul-searching exercise, but soon I found the cold. From there, I developed specific breathing exercises and did regular cold-water immersions.

The mindset part is a result of learning we are so much more capable of dealing with stress — physical, mental, biological, and emotional — than we previously were aware.

Stress control derived from regular practice in the cold makes you confident and very adaptable in daily life.

So breathing, cold, and mindset are the three pillars of the Wim Hof Method that give way to learning how to deal with stress of any kind.

So the Wim Hof Method is a lot more than just breathing and exposing yourself to cold? It sounds like it involves a lot of “life-coaching” ideas too.

The method is composed of three pillars as mentioned previously, but the outcome is more than just physical — it’s spiritual.

It is about love for all: nature, yourself, others, and all sentient beings. This is what you get when stress in your life is no longer a nuisance. You become more peaceful and full of uninhibited flow. It’s spirituality, with two legs firmly on the ground.

Which parts of your practice specifically help you get more in touch with yourself?

If you go take the course, for example, you don’t think — you are. You get into the depth of the brain where normally you are not.

Killer No. 1 in society is cardiovascular disease. In every person on Earth, there are millions of little muscles helping to control blood flow. How do you train these muscles? By going into the cold. Blood flow will improve with training and will improve access to oxygen, nutrients, and vitamins for your cells.

Then the heart. Because we wear clothes all the time and avoid exposure to the cold, our skin becomes de-stimulated. All our thermal receptors, which are designed to pass on the cold and react to it, no longer do so effectively.

By exposing ourselves to cold, we give our heart relief, because all the millions of muscles that make up our cardiovascular system are being optimized, providing more access to energy.

What advice would you give to someone just starting out on the Wim Hof Method. What should they expect? How soon can you see results?

You see results — no, you feel results — within half an hour. Just do the breathing exercises. The first time you go into the cold, the first thing you do is breathe. You learn to change your chemistry through deep, specific breathing techniques.

What do long-term benefits look like?

You learn to control yourself, and you get a lot more confident. You are better equipped to deal with stress of all sorts; that means biological stress, emotional stress, mental stress, viral stress, and bacterial stress.

How did you discover The Iceman superhuman resistance to cold?

Let me say, everybody has this superhuman ability to regulate his or her own chemistry. Everybody. We have been showing this in comparative studies now in which we showed that the existing paradigm in medical science — that the autonomic nervous system cannot be influenced by humans at will, nor the endocrine system nor the immune system — we have shown that we can tap into all three consciously. We changed science there, fundamentally.

So how did I do it? I went into nature, challenged myself, challenged my mind, challenged my body, and then came back to research institutions to show how simple but very effective techniques allow us to go deeper, and suddenly do what seemingly was impossible for humans to do.

You’ve spoken often about your early “soul-searching” days. Which other practices have you found fulfilling, and were there any practices you think are bullshit?

I found a lot of bullshit practices. Bullshit to me. That is to say: too far-fetched, too obscure, too complicated, too esoteric. They did not appeal to the depth of connection I was looking for. The cold brought all that “hamstering, circling mind” to a stop. The cold stills the mind, it gives you instant power and a deep connection.

Suddenly, I was at the steering wheel. The journey began, though everybody thought I was crazy.

I felt great doing my daily practice, yet it took 25 years to get the mainstream to respect what I was doing.

From crazy, to The Iceman and scientific validation, has been a journey of holding on to my beliefs and practice.

Now, we have shown that it works and helped people all over the world realize deep, tangible results in a very short period of time.

You’ve been challenged before for suggesting The Iceman Wim Hof Method works for cancer patients or for people suffering from terminal diseases. What’s your current position?

We always state that the method is not a cure, and that people should consult their medical doctors to see if they can use the Wim Hof Method as an ad-on therapy. This is policy, and this is something that we do not stray away from.

My personal position toward people who suffer from cancer or other terminal diseases is still to inform them that there is so much more than what contemporary science is telling us is possible.

Healing powers within people’s physiology are incredibly undervalued. Too often, we overutilize pills, medicines and depend too heavily on doctors. There are more natural internal methods to be discovered and used to battle what is happening inside our bodies and minds.

It’s more logical to focus inwardly than to continue relying on external dependencies. I have shown this, and it’s been proven scientifically. It is my belief that this is the way forward, and I will solidify it more and more through nonspeculative comparative science, using rigid data.

I have seen so many people be healed. I am convinced that we have much more power inside us than what we know or is being let on.

In consultation with their doctor, people should try the method out for themselves to see what it does for them.

How do you deal with fear when you’re out trying to break a world record or do something most people would consider incredibly dangerous?

There is danger in nature. You always see it coming. You always feel it coming. It’s very clear. Only society is sneaky. In society, a lot of people get diseases, depression. It sneaks in. You don’t feel, you don’t see. In nature, you always see the danger coming. You always feel the danger coming. And you never cross the line.

What is your opinion on the state of healthcare in western countries? Are you an advocate for alternative medicines and holistic treatment across the board in all areas of life?

How can you develop a model monetizing our sickness? You don’t want anybody to be healthy if you make money off of people who are sick.

People advertise all kinds of pills and medicines all over the world, and they get it into our systems, get it into the new doctors, that it is normal to be sick and to be treated.

If they see arthritis, they see six kinds of medicines behind it, all approved by the FDA and the ethical commissions of the pharmaceutical industry through research. But there is no research showing how to heal without medicines, and I know those ones. We have showed with thousands of people, hundreds of thousands of people, healing through no medicine, no pill, just their own belief, breathing, and cold exposure.

What are The Iceman health tips in other areas of life? What tips do you have outside of the Wim Hof Method?

I like to do high-intensity interval training myself. I like the cold obviously, or anything I can come up with. I like playing guitar, singing, painting, and doing crazy stuff with my little one, or being outside in the garden. It’s all there. It’s very obvious.

What are your thoughts on marijuana and alcohol?

I’m not drinking anymore, and I feel great. And weed, I’m not smoking weed. I smoked hashish when I was in my 20s, and it was amazing. I’ve done anything that is prohibited by the church. And I enjoyed it, I loved it. But I am enjoying not needing it. Now, I just say, “Get high on your own supply.” The breathing really does it and cold does it, intensity training does it. And my cute little son, he does it, too, because he’s ridiculously beautiful.

The Incredible Achievements of The Iceman

Wim Hof first started gaining notoriety for his Arctic antics when the Guinness Book of World Records crew caught wind of a crazy Dutchman doing insane stuff in the ice. Since then, he has racked up an impressive 26 world records and successfully completed a range of other superhuman feats, such as:

- Running a half marathon barefoot above the Arctic Circle, wearing only shorts

- Hanging on one finger at an altitude of 2,000 meters

- Swimming underneath ice for 57.6 metres

- Climbing Kilimanjaro and Everest while wearing only shorts

- Running a full marathon in Africa’s Namib Desert without drinking

- Standing in a container while covered in ice cubes for extended periods of time

Most Importantly perhaps: Shown scientifically that the autonomous nervous system related to the innate immune response can be wilfully influenced, something that was previously unknown to science.

Webmaster Note: The Iceman Wim Hof has not totally shunned technology and Western World. He now operates an online learning environment, complete with the inner fulfillment possible through eCommerce. He also apparently maintains Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest accounts. You wonder where he keeps his phone, right?

Confederate Names on U.S. Army Bases

What Gives with the Confederate Names?

If you’re able to clear away the smoke and tear gas of 2020 — no easy feat, mind you — a loose, central question to much of all this noise is: Why should things stay this way just because they’ve always been this way? Social issues running the gamut from policing to statues of dead people in parks to names of programs at universities have brought to the forefront demands for immediate change and action during this, our 21st-century Summer of Rage. Continue reading “Confederate Names on U.S. Army Bases”

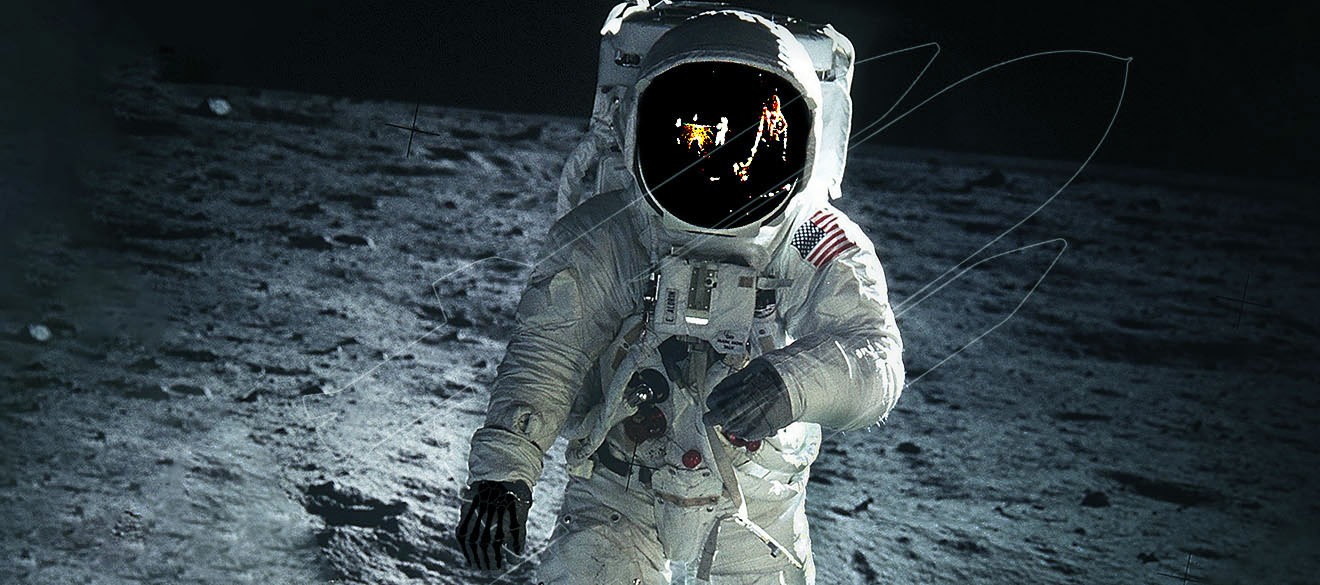

Astronauts and the Side Effects

Penthouse takes a brief moment to think about some things most of us have probably never considered as we dreamed of being Astronauts.

The Effects of Space Travel on Astronauts

What happens to our bodies in space?

Astronauts become TALLER. The lack of gravity causes vertebrae to expand, which lengthens the spine.

Space travel gradually flattens the back of the eyeball. Forty-nine percent of long-flight astronauts report vision problems that can persist for years afterward.

Loss of cardiac muscle leads to reshaping of the heart, making it more spherical. Irregular heartbeats and arterial hardening have also been reported.

Exposure to reduced gravity causes muscle fibers to shrink almost immediately.

In space, an astronaut gets exposed to high levels of radiation, which can lead to radiation sickness, cancer, central nervous system effects and degenerative diseases.

Someone in space loses the same amount of bone mass in one month that a woman with postmenopausal osteoporosis can lose in a year.

Astronauts have been shown to lose 1/4 of their aerobic capacity after just two weeks.

On the other hand, just imagine a view like this unobstructed by the atmosphere:

You would also be at least temporarily free from what can be a hugely annoying bit of modern life. We did think of a real downside, however. The nearest Ben & Jerry’s will be a really long drive.

SOURCE: madgetech / images: Nasa

Feast on Thanksgiving Cam Girls

Think about it: Thanksgiving Cam Girls. What a concept!

There are a million reasons why we’re thankful for cam girls. For one thing, they’re nice to look at. They also make great friends. They make even better friends with benefits. They give amazing pussy play videos. They fulfill every last dirty fantasy we have. And they have the power to turn Thanksgiving into one hell of a fuck fest … or, shall we say ‘fuck feast’ … yeah, we’re pretty thankful.

We can Zoom with family and friends while cooking a giant feast all for ourselves. Of course, this isn’t as exciting as spending the evening with our loved ones … or with a hot chick who can make us “especially” thankful.

Just because Thanksgiving will be in isolation this year doesn’t mean you have to actually “isolate.” Camster.com has thousands of sexy cam girls all over the world who are feeling raunchier than ever. Most of them have spent the last eight months indoors so they’ve been looking for someone to satisfy their cravings and “stuff” them real nice.

Camster is also offering different contests for Thanksgiving. There’s the Thanksgiving Discount, which comes with fun prizes for models. There will also be the Black Friday Blowout where models can win up to $2,000!

So which girls are worthy of the prize? There are thousands to choose from, but keep an eye on the five girls below. These girls have been spending extra time online so they can win something special for the holiday season … while spreading their legs and playing with their tits in live sex chat.

“Sabrina has that smart sexy look. She is gorgeous and knows how to make your time with her outstanding. Such a tease and makes the experience super exciting as she is very playful and engaged.”

“Where do I begin? Beautiful, kind, caring, loving, sensual, enticing. All words to describe the very beautiful Ella Claire. Be care if you visit … you will leave a part of your heart. But do not take my word- visit and find out for yourself.”

“She gets more beautiful with time. Her privates get more intense (if that is humanly possible). She has the beauty and knows how to work it to her advantage. Simply amazing.”

“Her amazed beauty will make your heart skip a few beats and take your breath away. She is the definition of being amazingly beautiful.”

“This woman has the most perfect tits just needing to be sucked. Her pussy, wet as she squirts all over. Her ass, perfectly round and tight as she fucks her hole. You will not be disappointed taking her to private!”

Get your private show this Thanksgiving with thousands of sexy cam girls on Camster.com! …

(And explore some of our earlier features, should you be feeling in a mood for dessert..)

Who hates Bill Gates?

Ever wish you could predict the future? Bill Gates can.

“If anything kills over 10 million people in the next few decades, it’s most likely to be a highly infectious virus rather than a war. Not missiles, but microbes. Now, part of the reason for this is that we’ve invested a huge amount in nuclear deterrents. But we’ve actually invested very little in a system to stop an epidemic. We’re not ready for the next epidemic,” the Microsoft co-founder said at a TED talk in Vancouver in 2015.

Gates, the second richest person in the world with more than $113 billion in assets, has also put his money where his mouth is through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Established at the turn of the century and endowed with close to US$50 billion in assets, it has created financial incentives for the pharmaceutical industry to develop vaccines and therapies to address cholera, typhoid, malaria, polio, HIV/AIDS, diarrhea, and other diseases that continue to kill millions in the developing world.

More recently, the Gates Foundation announced a US$250 million donation for COVID-19 research and relief — ten times more than Gates’ protege Mark Zuckerberg pledged, yet only a quarter of the billion-dollar pledge made by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey. Nonetheless, Gates, who has donated more than $50 billion since 1994 and on paper plans to give away another $100 billion before he passes, is not only the most generous person in the world but the most generous person who ever lived.

But in recent months, Gates, 64, has also become one of the most hated people in the world. According to conspiracy theorists, he is an Emperor Palpatine-like character who has masterfully convinced us of his benevolence, while secretly plotting to implant microchips in people through COVID-19 vaccines in a plot for global surveillance and population control.

Since resurfacing on YouTube, Gate’s TED talk has been seen more than 64 million times and has been used by anti-vaxxers to argue Gates had foreknowledge of COVID-19, and that he cooked up the virus in his lab. Theories linking Gates to the pandemic were mentioned 1.2 million times on television and social media between February and April, making misinformation about the tech baron-cum-philanthropist the most widely spread COVID-19 falsehood, according to media intelligence company Zignal Labs. The second most popular conspiracy theory blames the pandemic on 5G wireless technology and towers.

Investigations by reputable fact-checkers like The Poynter Institute, First Draft, and the American Broadcasting Company that have shown time and time again no evidence exists to back the microchipping theory have not blunted the resolve of the anti-Gates camp. In the U.S., 44 percent of Republicans and 19 percent of Democrats believe Gates is out to get them, according to a survey by Yahoo News.

“Sometimes conspiracies are true. They are not conspiracy theories They are conspiracy facts,” tweeted Michelle Malkin, a political commentator with 2.2 million followers who’s been denounced by Jewish groups because of her support of Holocaust denialists. “There was a poll this week, I can’t remember how many people…what the number was…but it shows [an] increasing number of people have stood up and said I will not take the Gates Vaccine. I will not bow down to jackbooted globalists,” Malkin wrote.

The Bill Gates conspiracy movement introduces some very interesting questions: Why are so many people, many of them educated and worldly, so willing to believe a man committed to ending poverty and saving lives is the devil incarnate? What does Gates himself make of all this? And is there anything fundamentally wrong with a billionaire subsiding the healthcare that governments have failed to provide?

ABOVE SCRUTINY

Not only is Gates the world’s most generous man, but he’s also the smartest, according to Inside Bill’s Brain, a hit new Netflix docuseries. Gates is capable of reading “150 pages per hour” with “90 percent retention” and has a mind like a “CPU,” the series claims, citing his “encyclopedic assessment” of mosquitoes and how these insects transmit disease.

Inside Bill’s Brain also paints Gates as a man with a heart of gold. “Three million times a year parents are burying children because of diarrhea. And in the world where I am spending time in, I’ve never met a single parent who had to bury his child because it died from diarrhea,” Gates said of the moment he decided to reinvent toilets in the developing world.

However, Inside Bill’s Brain is not an objective documentary. It is a carefully calibrated public-relations stunt created, directed, and narrated by a close personal friend who glosses over the back story of how Gates got so bloody rich to begin with: by using monopoly tactics in the software sector that eventually compelled Microsoft to pay billions in fines and settlements for breaching antitrust laws.

“There are not too many people who can be Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker at the same time,” says Dana Gardner, an analyst who has covered Microsoft for more than a decade, told PC World magazine. “To a lot of people, he was the evil empire. He stifled innovation and creativity. He was aggressive in business. Not just aggressive, but hyperaggressive.”

The Gates public-relations juggernaut is not limited to Netflix. Since the pandemic began, Gates has thrust himself into the spotlight as a global vaccination figurehead, appearing on TV, and penned op-ed pages for the likes of The Washington Post that criticize the Trump administration for its lackadaisical handling of the outbreak.

Gates has also criticized the Trump administration for withdrawing funding for the World Health Organization (WHO), whch publicly praised the Chinese Communist Party for a “speedy response” to the new novel coronavirus. However, it was later discovered China labored to cover up the virus in the beginning — a move contagious disease experts say made the pandemic 20 times worse than it would otherwise have been.

Interestingly, the U.S. funding cut made the Gates Foundation WHO’s largest single donor to a tune of $150 million per year, giving Gates even more clout to shape his global health agenda. Inasmuch Gates has shown that philanthropy is a clear path to power and that the healthcare of billions of people is wholly dependent on unelected billionaires like himself.

“I do not think that most billionaire philanthropists have bad intentions, quite the opposite in fact,” says Gwilym David Blunt, a lecturer in international politics at the University of London. “[But] we should ask why we don’t have stronger international organizations that are not beholden to wealthy states or persons [because] too many people in the world have to rely on the generosity of philanthropists. It’s a stark illustration of the gap between the very rich and the very poor.

“You might say that the world is a better place for having billionaire philanthropists in it,” Blunt argues. “That is true. But no one with such power can be above scrutiny.”

BOGEYMAN FOR THEORISTS

Being skeptical about the benevolence of billionaires is reasonable. But writing (or believing) reports by untrained journalists and anonymous bloggers who claim Gates tests his vaccines on Africa’s poorest, maiming and killing thousands of little kids, is not. Nevertheless, misinformation has in recent months proved to be as contagious as COVID-19.

Kate Pine, an adjunct professor at Arizona State University studying psychological reactions to COVID-19, says people are more willing to believe outlandish claims when “they’re inundated with information, but they don’t have the information they want.”

John Cook, an expert on misinformation with George Mason University in Virginia concurs. “When people feel threatened or out of control or they’re trying to explain a big significant event, they’re more vulnerable or prone to turning to conspiracy theories to explain them,” he wrote in an essay for The Conversation. “It gives people more sense of control to imagine that rather than random things happening, there are these shadowy groups and agencies that are controlling it,” he wrote, adding: “Randomness is very discomforting.”

Matthew Hornsey, a social psychologist at the University of Queensland, argues the uncertainty of COVID-19 and restrictions of individual freedoms created a “perfect storm” for conspiracy theories. This includes anxieties about mass surveillance and COVID-19 government apps that exacerbate fears about the potential for microchipping.

“The fear of insertion of tracking chips and other things like that into our bodies has been a longstanding bogeyman for theorists,” says Mark Fenster, a University of Florida law professor. “There is a lot of tracking that goes on. But the suggestion that it’s being used in this manner and this way seems absurd.”

And while it may sound like a conspiracy theory, the Russian government is partly to blame for the Gates-microchip conspiracy, too. In May, the head of the Russian Communist party said “globalists” were supporting “a covert mass chip implantation” agenda. A U.S. State Department report recently found Russia is spreading misinformation about COVID-19 through “state proxy websites.” Don’t trust the U.S. government? Well, you shouldn’t. But the website of Zvezda, a TV channel run by Russia’s ministry of defense, claims “the head of Microsoft held a conditional exercise called Event 201, which simulated an outbreak of a new virus that killed 65 million people in 18 months.” The simulation did take place, but at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, the world’s leading authority on contagious diseases. And it was designed to help governments plan fast and effective responses — not as a dry run in an evil plot to eradicate an unwanted chunk of the human population.

For a long time, Gates refused to comment on the online war being waged against him, leaving it up to employees like Mark Suzman, CEO of the Gates Foundation, to put things right. “It’s distressing that there are people spreading misinformation when we should all be looking for ways to collaborate and save lives,” Suzman said. “Right now, one of the best things we can do to stop the spread of Covid-19 is spread the facts.”

But in June, Gates finally let her rip. “It is troubling that there is so much craziness,” he told the BBC. “When we develop the [COVID-19] vaccine we will want 80 percent of the population to take it, and if they have heard it is a plot and we don’t have people willing to take the vaccine that will let the disease continue to kill people.

“We are just giving money away, we write the checks,” Gates insisted. “We do think about let’s protect children against disease, but it is nothing to do with microchips and that type of stuff. You almost have to laugh.”

EYES WIDE SHUT

Part of the appeal of conspiracies is that their creators tend to be outsiders — independent sources who generally lack relevant experience and expertise but consider themselves the only ones in the world smart enough to see a higher truth.

Conspiracy theories are self-serving because they “can never be disproven,” explains Jennifer Mercieca, author of Demagogue for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump. “He who wields conspiracy is very powerful because he can point suspicion in any direction he likes.”

But when conspiracies are exposed by reputable sources and backed up with detailed numerical research that takes time and patience to absorb, the public uptake is much slower — if at all, according to Cook from George Mason University. “Our brains are built for making quick snap judgments. It’s really hard for us to take the time and effort to think through things, fact-check, and assess,” he says.

The Bill Gates’s Charity Paradox, a lengthy investigation published by The Nation, offers a textbook example. The author, investigative journalist Tim Schwab, looked into more than 19,000 different charitable grants made by the Gates Foundation. His findings are startling.

In the past 20 years, the Gates Foundation made philanthropic grants worth $2 billion to multibillion-dollar corporations like GlaxoSmithKline, Unilever, IBM, and NBC Universal Media. Schwab also found around $250 million in grants given to companies in which the Gates Foundation holds shares or bonds: Merck, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Vodafone, Sanofi, Ericsson, LG, Medtronic, and Teva, to name a few. “A foundation giving a charitable grant to a company that it partly owns — and stands to benefit from financially — would seem like an obvious conflict of interest,” Schwab wrote.

The Gates Foundation refused to answer Schwab’s questions, saying only that “grants are implemented through a mixture of nonprofit and for-profit partners, making it difficult to evaluate exact spending.”

No Such Thing as a Free Gift, a book by University of Essex sociology professor Linsey McGoey, also uncovered huge philanthropic grants made by The Gates Foundation to for-profit companies, including a $19 million donation to a Mastercard affiliate in 2014 to promote the usage of “financial products by poor adults.”

“It’s been a quite unprecedented development, the amount that the Gates Foundation is gifting to corporations,” McGoey wrote. “I find that flabbergasting.”

Even more alarming is the fact that all these grants are tax deductions.

“By Bill and Melinda Gates’s estimations, they have seen an 11 percent tax savings on their $36 billion in charitable donations through 2018, resulting in around $4 billion in avoided taxes,” Schwab wrote. “[But] independent estimates from tax scholars…indicate that multibillionaires see tax savings of at least 40 percent. For Bill Gates, [that] would amount to $14 billion — when you factor in the tax benefits that charity offers to the super rich.”

Despite the multibillion tax trick Schwab’s investigation unearthed, The Bill Gates’s Charity Paradox It’s been mentioned by more than one person. Maybe change to “has been mentioned by few on Twitter, including: Titus Frost, an anonymous self-declared “journalist” and “researcher” with more than 20,000 followers. His tweet on Schwab’s investigation generated nine likes from his followers, the same number generated by another post Frost shared headlined “Pirates Versus Gay Pedo Wizards.” Meanwhile, the #ExposeBillGates hashtag has been retweeted more than 178,000 occasions and accompanied by claims Gates is plotting to block out the sun.

HOW TO ARGUE WITH FOOLS

I’m at a bar talking to a woman. She is well-traveled and has interesting things to say. But when the topic of COVID-19 comes up, she brushes her hand through the air to indicate it’s all nonsense. “I will never take the coronavirus vaccine,” she says. “I don’t need it. I can cure myself. If I have children, I will never let them get vaccinated with anything.”

I ask if she was vaccinated against measles, whooping cough, and polio as a child. She says she was.

“Those vaccines probably saved your life or in the case of polio, your legs,” I tell her. “You benefitted from them but now hate them? And you won’t let your children benefit in the same way?”

“I can cure myself,” she repeats. “Anyone can. We have natural immunity. Look at a tree. If you cut a branch off, it doesn’t go running to the hospital. It secretes sap to heal itself.”

I am tempted to tell her she’s a moron who couldn’t cure a rasher of bacon let alone a virus that has baffled every single scientist on the planet. But I know nothing I say is going to change her mind, so I mumble an excuse about being late for something and take my leave.

“It’s hard to argue with conspiracy theorists because their theories are self-sealing,” says Cook of George Mason University. “Even the absence of evidence for a theory becomes evidence for the theory.”

But other experts say it is possible to argue with conspiracy theorists — and to change their minds.

The one thing you should not do when trying to debunk a conspiracy theory is to take poke fun at it or repost it on social media while poking fun at it, writes Whitney Phillips, co-author of You Are Here: A Field Guide for Navigating Polluted Information.

“Making fun of something spreads that thing just as quickly as sharing it sincerely would [because] the information ecology doesn’t give a shit [about] why anyone does what they do online. Sharing is sharing is sharing,” Phillips says, adding that respectful engagement is far more effective.

“From there you can aim your debunking at a target, like shooting a water gun through a hole in a fence,” she argues. “There’s no guarantee the person will be convinced by your correction, but at least the message is going to land where they can see it. Hooting jokes about the theory, in contrast, is like throwing a bucket of water at the same fence. You might make an impression on passersby, but otherwise, all you’ll have is splashback.”

Is detailed research-based argument — the method I have used in this article — a better way to sway the minds of conspiracy theorists?

Not according to Professor Mark Lorch, who teaches public engagement and science communication at the University of Hull in the U.K., who cites the popular science-entertainment TV show Mythbusters to prove his point: “You might be tempted to take a lead from popular media by tackling misconceptions and conspiracy theories via the myth-busting approach. Naming the myth alongside the reality seems like a good way to compare the fact and falsehoods side by side so that the truth will emerge. But it appears to elicit something that has come to be known as ‘the backfire effect’ whereby the myth ends up becoming more memorable than the fact.”

A more effective strategy, Lorch says, is to altogether ignore the myth or conspiracy theory and get straight to the point with short, sharp, accurate jabs.

In the case of the woman I spoke with who thinks she can cure COVID-19 and vaccines are harmful, what I should’ve said, according to this expert, is that “vaccines are safe and reduce your chances of getting the flu by 50 and 60 percent. Full stop. Next subject. What do you think about Bill Gates?”

For a more malevolent view of the situation, you might need to look back at our our most recent article on PenthouseMagazine.com to expand your imagination. For more on the Bill Gates Foundation, peruse away.

Germs in the Arsenal

Week after week early on, news about the coronavirus outbreak that began in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 kept getting worse. And with each passing day, the only thing we learned was how little we knew about it.

In places around the world, the number of infections and fatalities kept doubling. Every day brought another story of a city, region, or whole country on lockdown. As with any high-profile, high-drama story, misinformation spread wildly. And because so much of what we heard was contradictory, it was easy to become unsure about what material to trust. Paranoia seemed almost mandatory.

Initially we were told the virus was transmitted from animals to humans at an open-air “wet market” in Wuhan. Then we heard that China’s premier high-security bioweapons lab is only a few hundred yards from that wet market.

Chinese doctors suddenly appeared with dire warnings about the outbreak and then disappeared just as quickly, leaving the world wondering if they were permanently silenced by the virus or by authorities. Even though the World Health Organization early on declared this new strain of the virus to be a global health emergency, Chinese officials wouldn’t permit physicians from America’s Centers for Disease Control to enter the region and conduct independent tests.

Some Russian media outlets said the virus was an American-made bioweapon designed to cripple a Chinese economy that’s putting its United States counterpart to shame. Other outlets claimed Chinese military officials were making the same allegation.

Meanwhile, American radio host Rush Limbaugh said the virus is likely “a ChiCom laboratory experiment” being used as part of a grander Chinese scheme to destroy Donald Trump.

Others insisted Chinese scientists stole the virus from a Canadian lab, while some said it was part of a population-control plot hatched at a private British institute.

At the start, when the only casualties were Asian, there were rumors that the virus was engineered specifically to kill Asians.

It all sounds crazy, right? An engineered virus, not a tragic twist of nature?

Except it gets less wacky and paranoid when you consider that for centuries, governments, armies, and lone-wolf terrorists have deliberately infected people with deadly biological agents.

Did A Medieval Siege Launch the Black Death?

The earliest recorded occurrence of biological warfare comes in the Hittite texts of 1500-1200 B.C., which describe victims of tularemia — aka rabbit fever — being relocated into enemy territory to cause an epidemic. In the fourth century B.C., Scythian archers would dip arrowheads into animal feces to add infectious potential to their flesh-piercing points. Ancient Roman warriors were said to dip their swords into excrement and corpses, leaving victims both slashed and infected with tetanus.

In what may be history’s deadliest use of bioweapons, the outbreak of bubonic plague — the Black Death — that ravaged Europe in the mid-1300s may have started, some believe, during the 1346 siege of the Crimean city of Kaffa, when the plague-infected corpses of Mongol warriors were tossed over walls into the fortified town. It’s speculated that the inhabitants of Kaffa were then infected, leading to a continental domino effect that may have snuffed out as many as 25 million European lives.

The last known incident of an army attacking its enemy with plague-infected corpses occurred in 1710, when Russian aggressors tossed cadavers over the walls of Reval in Sweden.

It’s well known that the European conquest of the New World was facilitated far less by military aggression than by all the diseases — smallpox, measles, influenza, the bubonic plague, and more — Europeans brought over with them. Some historians estimate that these scourges killed up to 95 percent of the New World’s indigenous population. However, this mass death was almost entirely accidental. The only recorded incident of a deliberate sickening of native people involved the “gift” in 1763 of two smallpox-infected blankets from British soldiers to Delaware Indians. A letter from one British commander to another expressed the intent to “Inocculate the Indians by means of Blankets, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race.”

Though it’s not clear whether the blankets successfully transmitted smallpox to the Delaware Indians, smallpox subsequently took the lives of 500,000 to 1.5 million Native Americans.

World Wars, Biobombs, and Fever Spray

The first World War brought unprecedented carnage to Europe. It also featured more sophisticated methods of germ warfare, thanks to advances in microbiology. German agents used anthrax and glanders to weaken Romanian sheep, Argentinian livestock, and French and American cavalry horses. On the flip side, French saboteurs infected German-bound horses with glanders.

As for World War II, evidence strongly suggests that in the Battle of Stalingrad, Russian forces deliberately infected up to 100,000 German soldiers with a rare respiratory form of rabbit fever. The mode of transmission was most likely an aerosol spraying campaign. The most notorious WWII bioweapons facility was the Japanese military’s Unit 731, a sprawling compound of 150 or so buildings near the Chinese city of Harbin. By deliberately planting typhoid fever and cholera into Chinese water systems, as well as dropping ceramic containers holding plague-infected fleas onto Chinese cities, Unit 731’s biological weapons are thought to have killed anywhere from 200,000 to 580,000 people.

In what was known as “Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night,” Japanese forces planned to target San Diego with balloons containing plague-infected fleas, but Japan surrendered a month before the operation’s launch date.

The Cold War and Weaponizing Germs

Invading Russian forces captured some of Unit 731’s operatives, but most faced no postwar confinement (or prosecution) after cutting a deal with the Americans to share classified data about their unprecedentedly cruel experiments on live subjects. Throughout the Cold War, communist propagandists accused America of using bioweapons, whether against enemy forces during the Korean War or by systematically treating the Cuban populace as biological guinea pigs.

Although the U.S. denies these allegations — as you might expect — what’s undisputed is that America started its own bioweapons program during WWII and kept it running until the end of the sixties. The U.S. Army Biological Warfare Laboratories were established at Maryland’s Camp Detrick in the spring of 1943. Before being shut down by Richard Nixon’s executive order in 1969 — a year when the program’s budget approached $300 million — Army technicians researched smallpox, anthrax, brucellosis, botulism, plague, hantavirus, yellow fever, typhus, bird flu, and other diseases. The biological weapons they produced were then tested at Dugway Proving Grounds in Utah, as well as other open-air venues, often upon unsuspecting civilians.

During 1954’s “Operation Big Itch,” cardboard bombs containing hundreds of thousands of uninfected fleas were dropped to see if the fleas would remain alive and attach themselves to human hosts — which they did.

In May 1955’s “Operation Big Buzz,” 300,000 mosquitoes infected with yellow fever were dispersed by air and on the ground across parts of Georgia. And in “Project Bellwether” during the late 1950s and early 1960s, researchers at Dugway Proving Grounds continued dropping untold numbers of infected mosquitoes onto an unwitting American public.

During Senate subcommittee hearings in 1977, Army officials revealed that between 1949 and 1969, they conducted 239 open-air tests of biological agents on unaware soldiers and civilians. In September 1950, a U.S. Navy ship sprayed the pathogen Serratia marcescens toward the shores of San Francisco for a solid week. Subsequent testing revealed the pathogen had traveled more than 30 miles, leading to a sudden spike in pneumonia and rare urinary tract infections.

In 1951, the Army exposed African-Americans to the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus to determine if they were more vulnerable than whites to the infection.

In 1966’s infamous “Subway Experiment,” researchers dropped bacteria-filled light bulbs onto tracks in midtown Manhattan and discovered the microbes spread for miles.

In a 1968 report, the Army concluded that, “Similar covert attacks with a pathogenic disease-causing agent during peak traffic periods could be expected to expose large numbers of people to infection and subsequent illness or death.”

Since the Cold War was one giant death race, the Soviets were busy stockpiling their own caches of biological weapons. Together, the Soviets and Americans produced enough nasty germs and viruses to kill everyone on Earth several times over. In the 1920s, predating even the atrocities of Unit 731, Soviet authorities experimented with typhus, glanders, and melioidosis on live human subjects at the gulag on the Solovetsky Islands. In the 1970s, even though they had signed a pledge to discontinue bioweapons development, the Russians’ Biopreparat program employed an estimated 50,000 people.

Since humans are prone to error, this led to an accidental aerosol release of smallpox in 1971 that sickened ten and killed three. It also led to an accidental leak of anthrax in 1979 that claimed more than a hundred lives. It’s speculated that if winds had been blowing in the opposite direction, anthrax would have spread into urban areas and possibly killed hundreds of thousands. In a top-secret 1980s program ironically dubbed “Ecology,” the Soviet Ministry of Agriculture developed variants of livestock-killing diseases designed to be sprayed from airplanes over hundreds of miles.

Thirty years ago, after the lead Soviet scientist investigating the bioweapon potential of lethal Marburg virus died of the disease, authorities discovered that the variant taken from the man’s organs was more powerful than the original. The Soviet Ministry of Defense weaponized this new, super-deadly strain, which they called “Variant U.”

But lest you think it was only the Americans and Soviets, the U.K. conducted bioweapon experiments throughout the first half of last century and became the first nation to successfully weaponize biological weapons for mass production. British researchers also bombarded Scotland’s Gruinard Island with anthrax for more than half a century. Although Israel denies it, the International Red Cross reported that during the 1948 War for Independence, an Israeli militia released Salmonella typhi bacteria into the water supply of Acre, leading to an outbreak of typhoid fever in the port city.

During the Rhodesian Bush War (1964-1979), the Rhodesian government deliberately contaminated water along the Mozambique border with cholera. After the Persian Gulf War in 1991, Iraq admitted it had produced 19,000 liters of concentrated botulinum toxin, and loaded 10,000 liters onto military weapons. As far as China’s bioweapons program goes, it’s anyone’s guess. The country’s officials are masters of propaganda and secrecy, leading to the possibility that we may never be able to definitively rule out the idea of an intentional origin for this new coronavirus strain.

Biological Terrorism

Compared to conventional incendiary weapons, bioweapons are easy and cheap to produce — as well as difficult to detect. Not to mention a would-be DIY bioterrorist can take as many lives with a nickel’s worth of rogue germs as a government could with $10,000 in conventional weapons. The documentary Bioterror quotes Larry Wayne Harris, identified only as “a former member of a white supremacist group,” who explains how cheap and simple it is for ordinary citizens to acquire deadly toxins.

“Biologicals level the playing field,” Harris points out. “Before [there were] governments with massive stockpiles of nuclear weapons, with aircraft carriers, with all types of machine guns, stuff of this nature. The private populace did not have these. But trying to use a tank against a bottle of germs is stupid.”

In 1972, Chicago police arrested a pair of radical leftist college students who had planned to poison the city’s water supply with typhus.

In what’s known as the single largest bioterrorist attack in American history, in 1984, Oregon cultists who followed Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh deliberately poured a brown liquid containing salmonella into salad bars at ten local restaurants in an attempt to incapacitate a sufficient number of ordinary citizens to swing an election in the cult’s favor. A total of 751 people were poisoned, 45 of whom were hospitalized, but no one died.

In 2001, a week after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Americans were gripped with fear about a rash of letters containing anthrax spores that were sent to public officials. At least 22 people were made sick by the letters, and five people died, including two postal workers.

It remains to be seen how much total death and destruction this coronavirus pandemic will cause before a vaccine arrives, if one does.

Those who speculate about a lab origin for the virus can point to clues, rather than hard evidence or expert consensus. But is such speculation pure lunacy? It’s a pretty crazy world right now. Crazy developments seem the new norm. And bioweapons are very real. Sometimes it seems a little crazy thinking is warranted. Elton Cornell is a lover of fine wine, curvy women, and V-8 engines. He’s always right, but he takes no pleasure in it because the rest of the world is always wrong.

Historic Perspective on Germs

The strain of coronavirus that emerged in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, spread throughout the globe and is thus officially a pandemic — a term describing an outbreak occurring across multiple continents. The virus has claimed more than 300,000 lives as the world holds its breath and hopes things don’t go from very bad to apocalyptic.

The following diseases have led to the deadliest pandemics in history. Since these fatalities have occurred over centuries, even millennia, under conditions where record-keeping was often sloppy at best, the body counts are only estimated.

SMALLPOX (VIRAL)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 300-500 MILLION

Spread with alarming ease through contact with infected persons — or even items that they’ve merely touched — smallpox begins with a rash that leads to pus-filled blisters that lead to scabs and scars and lesions and howling pain and blindness and death. It’s been cutting human lives short for 12,000 years and was one of the deadliest agents in the near-genocide of Native Americans that occurred after Europeans arrived bearing their Old World diseases.

MEASLES (VIRAL)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 300 MILLION

Able to live two hours in airspace where someone’s coughed or sneezed, measles is so infectious it will sicken nine of ten unvaccinated/nonimmune people in one household. In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the U.S., but last year, with more kids not being vaccinated, cases approached 1,300. Globally, it still kills nearly a million annually. In 1875, on the island of Fiji, measles cut down a third of the population; survivors torched entire villages, often burning the sick alive.

MALARIA (PARASITIC)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 300 MILLION

Spread via mosquito bite, a staggering 350-600 million new cases of malaria occur every year with a fatality rate of just under a half of one percent. Malaria’s existence has been documented since at least the time of the ancient Roman Empire (where it was known as “Roman Fever”), and its prevalence is thought to have been a contributing factor in pulling ancient Rome down into the Dark Ages.

BUBONIC PLAGUE (BACTERIAL)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 250 MILLION

Transmitted through bites from fleas who became infected after sucking the blood of diseased rats, the bubonic plague almost wiped out Europe twice — during the Plague of Justinian (541-542), in which half of the continent’s population died, and during the more infamous “Black Death” (1346-1353), which by some estimates wiped out two-thirds of Europe’s entire population. The last great plague pandemic was in China during the 1850s and took out 12 million souls.

INFLUENZA (VIRAL)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 200 MILLION

History’s deadliest flu pandemic was the so-called “Spanish Flu” of 1918-1920, which infected one-third of the entire world’s population and killed anywhere from 50-100 million people. It coincided with World War I but almost doubled that bloody conflict’s overall death toll. It was so widespread that even the King of Spain and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson came down with the bug. There have been other flu pandemics such as the Russian Flu and the Hong Kong Flu, but none have come close to the Spanish Flu’s murderous ferocity.

TUBERCULOSIS (BACTERIAL)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 200 MILLION

Since it’s an airborne germ and the air is free, an estimated one in every three living humans has been exposed to TB. The infection will remain latent and non-transmissible in 90-95 percent of cases. But when the infection becomes active, symptoms include night sweats, chills, chest pain, and coughing up blood. If left untreated, TB can mean a quick trip to the grave.

CHOLERA (BACTERIAL)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 100 MILLION

Acquired primarily through contaminated water and causing dehydration, vomiting, and pale, slightly milky diarrhea, cholera has been documented since the time of the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates. It remained relatively quiet for several centuries, until a series of seven pandemics emerged from India’s Ganges River starting in 1817 and persisting through the 1900s. In the 1990s, a new strain of cholera was detected that may signal a looming eighth pandemic.

TYPHUS (BACTERIAL)

Estimated All-Time Death Toll: 50 MILLION