For more than two decades now, some of the most twisted, hilarious, shocking, satiric, brilliant, and original American art has been produced by a stocky, tattooed guy in St. Louis, Missouri, called Tom Hück. Much of that work—small-batch prints made from large woodcuts—began life in a studio and print shop just north of downtown in a neighborhood of brick-built former factories that got pretty gritty for a while but has bounced back recently, attracting artists, small startups, craft brewers, and the like.

Head to a certain stretch of Washington Street and you’ll see a storefront sharing a two-story building with Bootleggin’ BBQ. Across the broad street, the kind with diagonal parking, is the Brick River Cider company. As for that modest storefront, its window is home to a poster reading, “TOM HÜCK’S EVIL PRINTS: ST. LOUIS.” It’s got red and black lettering, with a logo of a grinning, googly-eyed devil. “FINE ART PRINTMAKING: PRINT OR DIE,” reads another poster. If that doesn’t get your attention, maybe the one carrying the print shop’s slogan—“DISGUSTING THE MASSES SINCE 1995”—does the trick.

Inside, the red and black color scheme continues. Young tattooed assistants dressed in black T-shirts stand at work tables, getting prints made. You can smell ink, paper, and oil. A monstrous piece of machinery—Hück’s custom-made printer—sits at the heart of the space. And startling woodcut prints, some as tall as eight feet, grace the walls. Every square inch of these illustrations is filled with detail, figures crowded into frame. There’s violence, sex, rural people behaving badly. I see weird bugs, demons, skulls. A KKK hood. A bare-breasted woman in bondage. But the vibe’s not exactly grim. There’s dark comedy.

There’s social satire, directed at inequalities and social oppression. Bodies and faces are stylized, features exaggerated, like in the id-powered cartoons of Robert Crumb.

And as in the medieval paintings of Holland’s Pieter Bruegel, or the work of eighteenth-century English satirist William Hogarth—two artists critics cite when discussing Hück’s prints—the imagery seems to capture stories in progress, with subplots and mini-dramas unfolding in the intricate details.

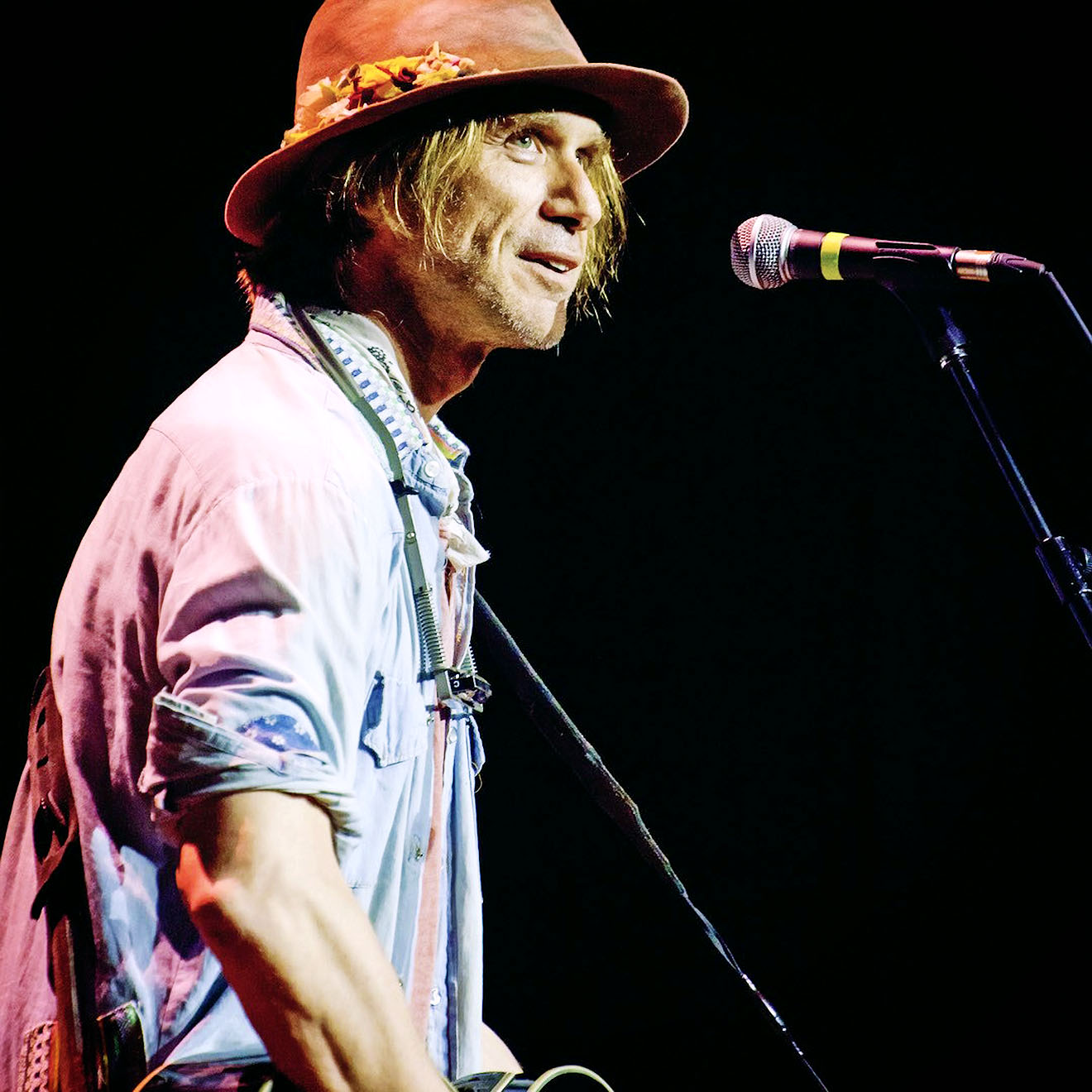

The effect of viewing multiple Hück prints at once is potent—like a boot to the gut. The print shop has a rebellious, underground feel, almost like a punk rock club. I see posters for thunderous bands like the Misfits and Motörhead on the walls. And then I meet Tom Hück himself, a bulldog of a man, 47, dressed in a black shirt and black jeans. With his Van Dyke beard and mustache, bald head, and sleeves of tattoos, he could pass for a Hells Angels biker, or an Iron Maiden roadie. But he’s warm, funny, and talkative.

Hück works primarily in woodcuts, ingeniously updating a painstaking, pre-modern form. He spends months into years on his bigger creations, if you count the composition time along with the carving. He often uses four-by-eight-foot plywood sheets. A world-renowned artist, Hück’s work has exhibited at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Harvard University’s Fogg Museum, and other prestigious venues. The Whitney owns a work titled Chili Dogs, Chicks, and Monster Trucks. Other Hück works are Up Dung Creek, The Transformation of Brandy Baghead, and Hillbilly Kama Sutra. Currently he’s spending time in Aberdeen, Scotland, on a two-year residency. While abroad, he’s creating an epic three-panel woodcut called A Monkey Mountain Chronicle: The Great American Turdburger Conspiracy.

The residency’s press release promises a work about “bad health care, conspiracy theories, fast food and fat America, and the coming, resulting apocalypse!”

Who are your artistic heroes?

Albrecht Dürer, that’s my hero. I found his work when I was 13 on a trip to Europe with my grandparents. I went to the Sistine Chapel and there was a gallery and they had all of Dürer’s apocalypse woodcuts. That’s a powerful thing to see when you’re 13. Those prints are dark and lurid. The horrors of Babylon nights—dragons, demons, devils. Any one of those prints by Dürer could have been a fucking album cover for Iron Maiden. Dürer was born in 1471, I was born in 1971. He was famous in the Middle Ages for his prints.

I mean, you’re talking a long time ago and this guy’s still relevant today. To me, and to most people who make prints, he sets the high bar for the craft and the medium. The way he synthesized his talent and his imagination, plus the fact that he could reach so many people with his graphic work. He was a smart cat. He figured out, Hey, I can make prints of originals to reach lots of people. I can get famous and make money. I can make copies of my stuff, printing with woodcuts and ink. I can have my stuff in multiple places at once, all over Europe.

How’d Evil Prints come about?

It started, what, 24 years ago? I can’t believe I’ve been able to make this thing survive for almost a quarter-century. I was 22, and came up with Evil Prints because, in the art world, for the longest time, printmaking had been associated with huge, famous shops—Tyler Graphics, Graphic Studio, Crown Point Press, Landfall Press. They would publish blue-chip artist prints. They were big, prestigious shops, and here I was, setting out to be a self-publisher.

I was making my own prints—there were only a few of us doing that. Richard Mock was one. Another was Bill Fick. He started this thing called Cockeyed Press. He’d do linoleum cuts, not woodcuts. These crazy monsters with really cool, dark imagery. They had social commentary about gang violence and politics. He’d make posters of these things, not prints, and they’d have slogans. He’d mail them to print shops across the country. People would get this badass poster and they’d be like, “Look at that.” They’d stick it up on a wall. And they’d get to know the work. The posters would say, “Published by Cockeyed Press, New York, New York.” I saw one and figured Cockeyed Press was major, like Graphic Studio or Tyler. Bill became my one of heroes. I even went out to visit him in New York.

So I go to Cockeyed Press and it’s a closet. I thought it was this big shop with assistants, people helping him, his elves. It was just Bill sleeping on a foam cushion underneath his press, in a closet in New York. I was like, Okay, I get it. It showed me the way. You could come up with a name and do it yourself. Evil Prints began in my parents’ basement. I didn’t even have a press. But I had a name. That’s how I started to compete with these big shops. This was 1995, before the internet took off.

I’d put a card out in the mail every three months with one of my images and the line, “Published by Evil Prints, St. Louis, Missouri.” People thought it was this big-time print shop. But it was my folks’ basement. Most people who do printmaking teach at universities. They use the university’s equipment, because this stuff is expensive. I used to teach, but I don’t anymore. I left teaching a decade ago. Over time, I just built up piece after piece of equipment, paying cash for it, and I’ve always had my own independent shop.

When you first meet someone, how do you describe what you do?

I want to be the Ozzy Osbourne of the art world—an American print warlord. It’s difficult, because the general population doesn’t know much about art. When you tell them you’re a printmaker, they don’t know what that is. I end up just saying I do drawings about how fucked-up we are as a society, and make copies of the drawings. People need to see the stuff. They get it after they see a print being made. When they see you carve it, ink it, and then run it through a printmaking press, they get it. A lot of people did some of that stuff in high school, with pieces of linoleum and even rubber-stamp printmaking.

My work mixes the whimsical and the terrifying. I want to ride a line between these two things. It’s a balance between the two—that’s what my heroes did. All the artists and musicians I love, they work this line, this balance. As far as being underground, I always say that printmaking in general is frowned upon by the art world. Hardly anybody knows anything about it, so we got that on our side in terms of punk rock credibility. When somebody doesn’t give a shit about what you’re doing, you can really sneak up on people.

How’d you get your work in museums?

When I started out, I was going around pitching my prints directly to museums—doing cold calls—which was unheard of. I got lucky, and sold to two really big museums right away. Before my work had even been seen by the public, Harvard’s Fogg and the New York Public Library bought from me. The Whitney came later, in 2000. Any bit of money that I can make off my work is a lot of fucking money. I’ve never lost sight of that. Over time, the more things sold, with the work getting known, the bigger it got. The more expensive it got.

When we were out on the road with the Outlaw Printmakers, we were tabling prints in rock clubs. Kids were coming up to my table and saying how much they loved my work, but said I didn’t have anything they could afford. That’s when I started making affordable prints. Stuff under $10 that I can crank out really fast. I print a lot of them. I do $10 prints, I do $25,000 prints, everything in between. Starting this fall, I’ll have a whole new body of affordable prints called Apocalyptic Pets. Adopt one, take one home. For ten bucks, you can get a print.

New York Print Week, every October, is big, and I’m fortunate enough to have a dealer like C.G. Boerner representing my work. It gives you visibility—a platform to be seen by the right people. If I hadn’t sold to museums right away, I don’t know if I’d still be here doing this. The business of art sucks, but I’m lucky being able to do museum-level stuff. I won’t bullshit, it’s something you think about when you’re a kid. Being in a museum. In my case, I make art that I want to look at. But I’m fortunate, because I know at a certain level if my stuff’s going to a museum, it’s going to live on a bit after I’m gone.

How’d you make Electric Baloneyland, from 2017?

Typically a print like that, they’re big triptychs. Three panels. That set took four years to do, and I was working every day on it. I also worked on small stuff. During the day, I go back and forth between projects. I’ve got to have small prints coming out all the time to fucking pay the bills. But larger things, they’re very mental, very physical. They take a long time to plan, a long time to do. I’m not one of these artists that just cranks something out. I think about stuff, and plan things out in my sketchbook a long time in advance. Woodcuts take a long time. In a way, the slowness of the project as I move it along allows me to get ideas for what I’m going to do next.

When people see my stuff, they’re like, What the fuck is going on here? They run away from it in a way, but they’re always drawn back in because they’re entertained. There’s a lot of craziness and repulsiveness you’ve got to deal with. I want people to come back to my work. I want them to be a bit horrified, but intrigued. I’m trying to take dark, lurid, terrible things, and make them beautiful from a craft perspective. That way I can get my point across—what I’m trying to say as an artist, a commentator on society’s ills. Again, it’s a balance. I’ve got a bit of the higher-brow stuff going on, too, which is the way it should be, if you’re making stuff that matters. But I want to get my stuff out to everybody.

Some of the biggest-name artists were printmakers, right?

Yeah, artists everybody knows—Picasso, Rembrandt, Matisse. They all made prints. Part of it was economic. It’s extra money. Prints aren’t as expensive as paintings, so it’s a common thing for artists of every caliber and level to engage in making them. Picasso was one of the most badass printmakers who ever lived. Rembrandt might be number two, along with Dürer. Goya’s a famous painter who’s also known for his prints. The German expressionists—Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka—they all made prints.

They wanted to reach a lot of people with very emotional, content-filled imagery. Quick Picasso story. When I was in kindergarten, we watched film strips. Actual film, on a reel. There was one with Picasso painting a bull on a piece of glass, but he was looking at us, the viewers, through the glass. He didn’t even look at what he was drawing. He was smiling, painting the bull. I was like, That guy is a badass! I want to be like that guy.

Can you tell us what Woodcut Bootcamp is? It sounds wild.

It started in 2006 as a way of making money in the summer, which is usually a terrible time for sales. Basically, it’s a ten-day intensive workshop where people come to study with me and I teach them how I make big woodcuts. They make one large woodcut print themselves. Usually about 15 people are all working and sleeping in my shop. It gets pretty smelly. It’s nonstop art-making. They’re all pretty beat by the end, but I guess it’s my way of keeping the woodcut tradition and practice alive by passing it on to other artists. They come from all over the world now!

During the workshop, I teach art-historical background, sketchbook and drawing approaches, and complex carving techniques. We also show them how to print these big damn blocks by hand or on a press. Woodcut Bootcamp now sells out every year and it’s become a sort of tradition out there in the world of printmaking. Those that survive it get a Dürer tattoo at the end. Almost like joining a cult!

Can you tell us about any new projects?

I’ve got the follow-up to Electric Baloneyland, A Monkey Mountain Chronicle. It’s about gluttony. Not necessarily or specifically American. I mean gluttony in terms of overindulgence in religion, food, politics. Overindulgence in sex, which I’m all for. It’s about over-the-top conspiracy thinking, overindulgence in bullshit. Nice, uplifting stuff.

It’s going to be a triptych on paper that actually folds up like an object. It’s big, and there’s a front, a back, and side panels. You’ll walk around it in a room. It’ll be displayed like an artifact. I’m working with Peacock Visual Arts in Aberdeen, Scotland, on it.

I’m also working on a smaller print set called The Four Seasons, which is all about global warming. I just finished Summer. It’s giant mosquitoes attacking fat people on a beach. Winter is a giant snow-cone tornado with lightning. Spring is going to be a plant basically strangling people with allergies. The fourth one, Fall, is going to be a Halloween/witch thing. I’m also doing an NRA beauty-pageant piece for Landfall Press. And The Tommy Peeperz is a triptych about the first time I saw breasts in real life.

It was June 15, 1983. About 1:30 in the afternoon at the local pool. Stephanie, the gorgeous lifeguard, dives in to cool off and the moment she hits the water her top comes down for a split second. I almost drowned. She was a senior in high school, I was in fourth grade. I was underwater, in the shallow end, with a snorkel and goggles on. I had a clear view of what happened. It was like something that was only there for me to see. It was fantastic enough that I’m still obsessed with it decades later.

All images courtesy of Tom Hück.