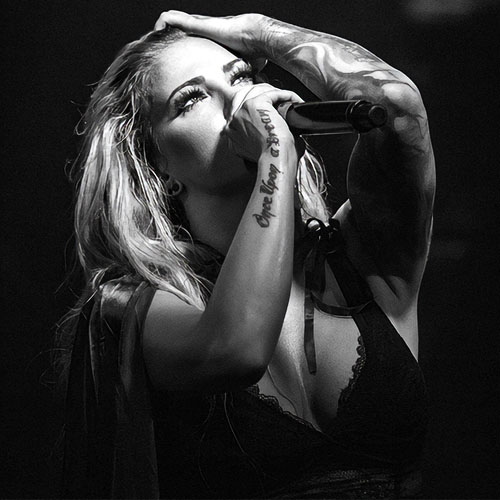

She lived with AC/DC, toured with Elton John and Suzi Quatro. Now, Tana Douglas, the first female roadie in the world, has written a book. So, what really does happens on tour?

Living Life … LOUD!

Tana Douglas was just 16 years old when she took her first job as a roadie with AC/DC. As the world’s first female roadie, she’s worked with some of the best known, most loved and infamous rock ’n’ roll bands. Her career spans more than 30 years and three continents. She now lives in California, and as she launches her first book, Loud, she speaks to Penthouse about her past, music, bands she loved — and loathed — life lessons and forgiving her mother.

Your book is a compelling read. How did you find the writing process?

It was tricky! I didn’t have any diaries to work from, so I found myself jumping back and forth between tours, trying to make sense of it all. It’s not an easy job making my story digestible for people to read and follow. I started writing and messed around for about a year. I put it down for a year and a half, and then came back to it. So, the whole process took about two and a half years.

Did the experience take over your life?

Yes! I converted a room into a writing room. There were Post-It Notes stuck all over the walls. I kept putting bits in and moving them around. It was like a huge jigsaw puzzle! It was strange, reliving it all, but it’s like free therapy.

You took your first job at 16. What advice would you like to have given to yourself at that age?

Run! No, but as strange as it may sound, it was the safest place for me to be at the time. Sure, parts of it were dark and sordid. People think, “These road crew people are rough. They drink a lot, do drugs. They’re on the road the whole time. They womanize.” But these bands took me in and adopted me, in a way. A lot were very protective of me. Although they weren’t aware of quite how young I was, right back at the beginning. There was a nurturing quality to them that they don’t admit to very often. It’s certainly not the side that people see. For me, it was a safe place to land. I could still be in Kings Cross [a red-light district in Australia], if I would even still be alive.

We’ll talk about Sydney, but first I want to discuss your early years. You start your book writing about being woken up by your mother and told you were leaving your home.

Yes, when I was four, I was taken from the only home I’d ever known in Brisbane in the middle of the night. My mother woke up me and my half-sister and said, “We’re leaving. We can never be happy here.”

And this all came as a shock to you?

Well, as children we thought we were happy. No further explanation was given. We were just woken up, and we left my father asleep in bed. It all went downhill rather quickly from there.

What do you mean by that?

My mother wasn’t stable; she had a lot of demons. She had a really serious road accident in her 20s, and we think that caused a lot of mental damage. It’s the only thing I can identify that I can use to justify her behavior. There’s no other excuse for her.

You write about her drinking and constant moving.

It all shaped my worldview. Growing up in that kind of turmoil, it makes it really difficult as you grow up. You have no clue about relationships. I didn’t know what a relationship was meant to be, or what a family is supposed to be like. In many ways, AC/DC — Malcolm and Angus [Young] especially — became like my family. A road crew is like a family unit; it made me feel safe. My father did try to fix me, but I was 11 by then and I was quite feral! He was saying, “Oh my God, let’s put her in a boarding school. Let’s try this or that.” I suspect he didn’t know how deep the damage was.

Music was an escape for you from a young age?

Yes, from a very young age. Janis Joplin, The Animals, The Stones — listening to music on a radio or stereo. When I listened to The Animals sing: “We’ve got to get out of this place,” I thought, Well, hell yes, sign me up.

Janis Joplin was a huge influence on you?

Her music is heart-wrenching, and I suppose I saw her as a bit of a role model — not that that’s a good thing in many ways. But she stood up for herself. She was a fighter. If I had any role model at that point, it would be her. I was always drawn to darker music because it reflected my life. I was never one for poppy, happy songs!

OK, let’s talk about Sydney, Australia. You write about “rubbing elbows with the Sydney mob.” Your encounters were terrifying, including one with a murderous pimp.

I’d come out of the rain forest, which was very not me. I was a little too organized, and I needed to be progressing in life. I ended up in Kings Cross. I adapted easily. I do tend to adapt well, and I found myself getting very sucked in to the scene there, very quickly.

It’s one of those areas in Sydney that has lots of characters.

Yes! Some of the strangest characters that you wouldn’t think had a soft side, but they took me in like a lost kitten. Terry the Kid was one of the Sydney mob who took a shine to me. He would take me to posh restaurants, like I’d gone to with my dad, and he’d order Bombe Alaska, which I loved. And he took me to Randwick Racecourse, which I always enjoyed.

But there was a dark side, too.

I had a lucky escape from a pimp, who was a really nasty piece of work. He basically decided I should be one of his girls. He had a group of very young girls, and I mean very young. I talked to them and befriended them. When he kidnapped me at gunpoint, he decided he was going to shoot me up with heroin, and I was to be one of his working girls. That was my signal. Something inside me just knew: “I’ve got to get out of this place.” And that was the change that got me into music.

Can you see a blessing in the way that all unfolded?

When I think about it, if that pimp hadn’t kidnapped me, and I hadn’t gotten scared and decided I had to make a change, I doubt I’d still be alive. Those young working girls don’t last long, unfortunately. So, I doubt I would have ever made it out of there alive. Plus, he was actually knocking off his girls, which I write about in my book, too.

Tell me about your bond with AC/DC.

They were still in the process of writing their first album. I was the band’s first backline roadie, which meant looking after the stage equipment, instruments and vocals for Bon [Scott] when rehearsing. The bond is so strong between us because we were all so young. It leaves an imprint on you. I was a very young girl, who’d run away from home. We were all learning, and that bond lasts a lifetime. Those guys will always have a special place in my heart; I couldn’t get rid of it, even if I wanted to. I’m so grateful, looking back. It could have been a very different situation. I mean, it’s not always good living in a house with musicians! But we had a family bond that was stronger than any of that side of band life.

So you’ll always be in touch?

Absolutely. Any time I’ve crossed paths with them over the decades, it’s been like stepping back into the same old shoes. It’s just there. And it’s something that I’m really grateful for.

Can you share a favorite memory?

I think the bonding times, especially when it was just the five of us — Malcolm, Angus, Bon, George [Young] with Harry [Vanda] coming back and forth. We’d sit around and listen to music for hours and hours, and talk about how it made us feel. Malcolm especially was very generous that way. He and Angus once put on Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel.” I ran from the room screaming, “No!” The only thing I’d seen of Elvis in my childhood was those horrible movies. “I can’t listen to this,” I said as I ran away.

Malcolm must have got up early to go to a record store because he came back home with a record that wasn’t widely released. It was called Insane Asylum by Kathi McDonald. He chose [the title] track, a version of “Heartbreak Hotel,” because she’d worked with Janis Jopin. And, specifically, he chose that song because he knew I’d relate to it. He said, “I want you to listen to this,” sat me down, played it, and I said, “I love it!” He said, “That album’s for you to keep.” Those sort of moments, when someone goes out of their way for you like that, they stay with you forever.

You say the Australian music scene revolved around the pub circuit.

At that time, yes. It was rough and ready! It was incredibly healthy. There were pubs everywhere. You could do 12 or 14 shows a week. When we were working, the manager, Michael, said, “Right, let’s put these guys to work.” And we did! I can still hear us playing at the Matthew Flinders Hotel on a Sunday afternoon. There would be over a thousand people watching. It was wild and woolly, you know! The Bondi Lifesaver was a bit trendier; the clientele were a bit more, how should I say, diversified. It was known as the wife-swapper. We looked at each other at one point and said, “We’ve done really well. We sold out four nights in a row.” AC/DC were a power to be reckoned with, that’s for sure.

And you were with them for years as they changed?

They certainly changed over the years. When Phil [Rudd] joined from Angry Anderson’s band [Buster Brown] that was a whole new scene. We toughened up pretty quickly! And you know, just because those fans had enjoyed seeing Phil in Buster Brown, didn’t mean they’d love him in AC/DC. And then, in country towns, guys had worked hard on those ranches since they were little. They don’t tend to like strange men coming into town and messing with their women! It’s not every day you have a knock-down fight with Deep Purple. Those things stay with you.

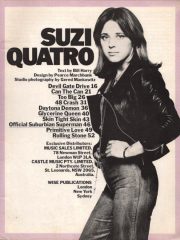

Talk to me about working with Suzi Quatro.

That was after I’d worked with AC/DC, the first time I’d worked with a woman. And I think it was the first time Suzi had a woman working with her. It was funny to watch the male audience members. There were grown men passing out. Oh, the memories of that! One time, at the Pavilion, the guys were passing young men onto the stage who’d been overcome by Suzi’s presence. Remember, there were no crush barriers in those days, so the guys would pick them up and pass them to the side. There was one guy lying in a hallway, and everyone was like, “What shall we do with him?” I was standing over him as he came round. He said, “Ohhhh, Suzi,” and passed out again. I was wearing a leather jacket, but if he was so far gone that he thought I was Suzi, he wasn’t with it! Somewhere, he probably still tells the story today about when he came round at a concert to see Suzi Quatro standing over him.

Tell me about the Wings tour party with Paul McCartney in the ’70s.

We threw a party for the Wings tour; it lasted three days! The neighborhood was a little over it by the end. All the Australian crew, the U.S. crew, the U.K. crew, then various members of bands turned up. Jimmy McCulloch, then the brass section of the band. It just kept growing. The police arrived, and we just said, “It’s a party for the Wings tour,” and they blocked off traffic to the street! The neighbors had been complaining for days, but the cops just blocked off the traffic. It was quite the bash, and you know, several people from that party have remained lifelong friends.

Three days worth remembering?

Well, three days well forgotten!

I loved your descriptions of life on tour in your book.

Life on tour gets very surreal. You’re living in a bubble. You lose touch with reality; there is no reality. These tours go on for 12 or 18 months, and if it’s a good team fit, you do it all again. You build up a tight affinity with each other. You don’t let outsiders in. If you know you can all rely on each other, you close the doors. You don’t like a stranger coming in, unless someone knows them and vouches for them. I got to the point where I didn’t bother to learn names. I’d automatically turn off and think, What’s the point of remembering, I’m never going to see them again. I still find myself doing it to this day. I’m still really bad with names. It’s a false world you’re living in.

And it’s hard to adapt coming out of it?

It’s really hard to adapt to coming out of it. Lots of musicians have serious mental health problems. With road crew professionals, you’ll find many have a hard time with their wives, partners, families or siblings. You’re so close to your bandmates, and then all of a sudden you’re thrust back into a world that’s alien.

We don’t tend to talk about mental health and the road crew.

There are organizations these days to address these issues, but back then there was no support. Remember, we’re alpha personalities. We don’t like saying, “I’m hurting,” or, “I can’t do this,” probably because we know if we do say that, someone else will come in and take our place. On tour, life doesn’t slow down.

You write that internationally touring bands were the real magic, as they gave you access to the world. Was traveling a priority for you?

It was the only priority to me! It was, without doubt, my highest priority. I never wanted more money, or anything financially precious. I just wanted more; I knew there was more out there, and I wanted to discover it all. I wanted to experience different cultures.

Has that love of travel stayed with you?

It hasn’t stopped! I haven’t stopped moving on! I’m somewhere for a few years, and then I want to continue learning. There’s forever more out there.

Tell me about Status Quo.

Status Quo is one of my darling bands, above most others. They were such fun to work with. Again, it was like a family unit. We built our own systems and worked with them directly, so that broke away another layer of separation. They’re funny guys, and they were at their peak. They were having a ball, loving the shows, loving their music, loving their fans. I worked with them at the perfect time. There’s a magic when a band’s first forming. They’re still fresh and so vibrant. I don’t like working for old, jaded bands, and, unfortunately, there are a lot out there!

What are your memories of Iggy Pop?

There was some guy at a show in the U.K., who was trying to get backstage at Iggy’s show. The guy didn’t have a pass. In fact, it was a prime example of me being bad with names. I got back to the dressing room and said, “He says he’s supposed to be here,” but I couldn’t remember his name. They asked, “What does he look like?” I said, “Kind of average, kind of old.” “What do you mean by old, how old?” they asked. “At least 27 or 28,” I replied. Then I realized that’s how old they all were. That was my cue to leave!

It was in 1970 on the Whitesnake tour that you found out you were pregnant. What memories does that bring back for you?

Getting pregnant wasn’t something that was in the cards, you know. It was terrifying to be honest. I got on a plane from Europe to Australia, and I fell apart. I didn’t know where to turn. I thought that Australia was at least the only place where I had a bit of support. I hadn’t seen my mother since I started working with AC/DC. We’d spoken, but I hadn’t seen her. I’d spent all my time around guys, and I had no one to talk to. I knew it would be a deal-breaker for my career. It was a huge decision to make, all of a sudden. I didn’t know how well equipped I would be to handle a family of my own. I didn’t want to deal with the father. But I had my son, and my mother decided it would be a good idea [for her] to raise him. We agreed that I would continue to work in Europe and support them both. It didn’t work out.

Your mother let you down again?

I thought she was better; I thought she didn’t drink anymore. She had a bigger place. I got her settled. She had a garden and was cooking and doing all sorts of things I hadn’t seen her do before. I’d heard stories about grandparents being closer to grandchildren than [their kids], and maybe it was just wishful thinking. Unfortunately, she still saw it as a way to torture me.

You ask in your book if you’re allowed not to love your mother.

Just because someone’s a parent, loving them isn’t obligatory. I understand there’s natural DNA, but that only goes so far. I can only speak from my own experience, but you have to decide if you’re prepared to love someone without any boundaries. I got to a place where I finally forgave her for what she did to me and my son. What’s that saying? Seek revenge, and you should dig two graves, one for yourself. Finally, I realized I had to let it go. I came to as much peace as I could find. But let me say, it wasn’t easy.

You have some memories of Elton John.

I worked with Elton for four years, which were during his difficult years. He went through a really rough patch. He threw great parties. People used to loving doing his tours for the eye candy because you never knew who was going to turn up. But he’s just not my kind of person. I’m not a fancy dresser. I don’t drive expensive cars. I don’t eat with gold cutlery. There’s a side to him that’s really nice, and that’s flourished later in life. He’s got a family now. He seems happy with his husband [David Furnish] and children [Zachary, 10, and Elijah, 8, who were born via surrogate in the U.S.]. At the time I worked with him, you couldn’t have paid me any amount of money to do another tour with him. So, it makes me happy to see he’s come through it.

In your book, you mention Yoko Ono and Sean, her son with the late John Lennon.

Yoko came onstage at Madison Square Garden to commemorate John. She had Sean with her. It was a big deal then. There were lots of security men in black around, maybe a dozen. They came up onstage with her. Remember her husband had been shot, and she had his child with her. I had a sweet moment with him, little Sean. They were dragging him up the steps, and his shoelaces were undone. I grabbed him, put him on my knee and started doing up his laces. All these men in black swarmed around shouting, “Freeze.” I said, “His laces are undone.” Sean smiled, gave me a hug, said thank you, and they whisked him up onstage.

In your epilogue you write, “If you want it done, leave it to a roadie.” Does that kind of sum it all up?

We roadies don’t mess around! We don’t have time for red tape. We just do the job. If anyone asks you do something, you just figure out how to do it. We find solutions. Management companies and agents, they’re the ones going through emails and contracts. When I was asked if I could get INXS, I said sure. I spoke to people I knew and made it happen. It’s just how you do it. You reach out to a friend. That’s just how we roll!

You also included a memoriam in the book. Was that your idea?

Yes, and it’s not a full list. It’s just a short list of people who have passed from within the industry and are relevant to the stories told in the book. Each chapter has a song title, which gives you some idea about what’s going to happen in that chapter. I also included a playlist. My book basically gives the reader broad coverage of three decades of music. I really hope people enjoy it.

LOUD: A Life in Rock ‘n’ Roll by the World’s First Female Roadie | Tana Douglas (ABC Books, $34.99). Buy the ebook via Apple. Should your tech be evolved beyond analog amps, you can also grab LOUD for your Kindle. As an unsolicited endorsement, we can tell you that at least one of the Kindle people here really enjoyed the “Loud” ride.

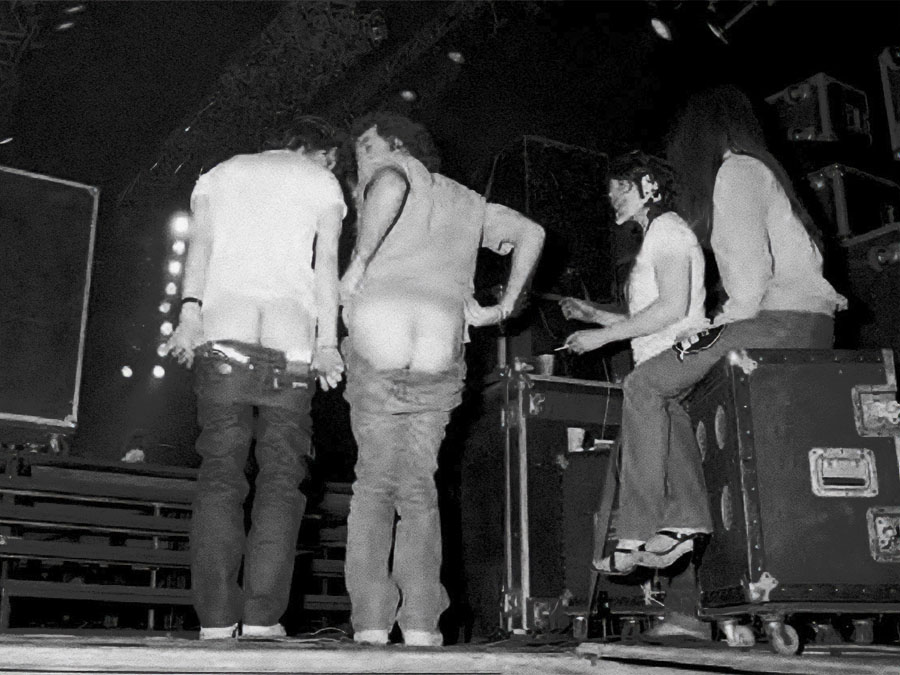

Welcome, Alain! The Quo initiation for a photographer new to our group, Alain le Garsmeur. Meanwhile I’m try to call the show.

For more Roadie Tales, you may look behind one of our other Penthouse Doors. Handy, that.