Almost two decades into the forever war, recruiting new servicemembers for the American military has become more complicated.

“When I came to this assignment, everyone said, Oh, you got it easy — the South? Military community? You got nuthin’ to worry about…but it’s been hard. A legit hustle. These kids grew up during the wars, seen their parents come and go. They know what military life is really like…can’t sell them on the perks, on the adventure. Yeah, the economy is good. That makes [recruiting] harder. Yeah, there’s a lot of kids out there who can’t qualify, because of the various requirements. Can’t speak to national trends. But here? Here it’s the wars, man. It’s killing me.”

Those are the words of a staff sergeant working as a recruiter in the United States Army in the summer of 2019. (He wishes to remain anonymous for, well, obvious reasons.) Recruiting fresh bodies and young minds to the armed forces is a tried and true tradition — the Roman Empire offered farms and a share of war spoils for aspiring legionnaires, while Napoleon’s recruiters used to frequent taverns late at night for recruits. Since the American green machine ended the draft and switched to an all-volunteer force in 1973, the onus of collecting new manpower lays entirely with recruiters.

It’s a dirty, often thankless job, but someone’s gotta do it. And it’s getting harder.

The Army fell short of its recruiting numbers goal in 2018 by a few thousand — the first time this has happened since the peak of the Iraq War in the aughts. (The Army’s just one branch, sure, but it’s by far the largest service, with 37 percent of servicemembers.) What the good staff sergeant above called “various requirements”? It’s a legitimate concern.

According to an August 2018 report in The American Conservative, “One in three potential recruits are disqualified from service because they’re overweight, one in four cannot meet minimal educational standards…and one in ten have a criminal history. In plain terms, about 71 percent of 18-to-24-year-olds (the military’s target pool of potential recruits) are disqualified from the minute they enter a recruiting station.”

It’s not just a skeptical mom these recruiters have to convince, these days.

“Yeah, we can get waivers for some physical/mental/moral character concerns,” an Army major who once worked as a medical recruiter at Fort Hamilton, New York, told me. “And you need to make the mission. That’s the job. But you still have to weigh that against putting these people in uniform. Would you want them in a firefight next to you? Would you want them running an aid station for combat casualties? Sometimes the answer’s no.”

Post-Vietnam, all the military branches have relied on a large stretch of the nation from Texas to Virginia to fill its ranks. Not coincidentally, this is the region where a majority of big military bases remain open. Anecdotally, most every single soldier in my 30-man scout platoon was from the South or Midwest, the lone exceptions being one Californian and one Haitian immigrant via Trenton. If what the staff sergeant recruiter’s dealing with becomes a trend, and if that trend holds? Well, something’s gonna have to give. Spoiler alert: It won’t be Uncle Sam.

I was recently in Puerto Rico for a reporting assignment, and attended a ceremony for graduating high schoolers across the island who are joining the military. Their recruiters from the Marines, Army, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard (yes, Coasties, naysayers!) came to join the celebration, dressed to the nines in their dress uniforms.

Puerto Ricans over-represent in uniform, per capita, compared to their mainland counterparts, and service is ingrained in the island’s history — even before becoming an American territory, it was a military colony for Spain, after all. Between the pomp and presentation of certificates to the new recruits, I asked some of the recruiters about their work.

One told me their job’s “regrettably” gotten a lot easier since Hurricane Maria, because of economic opportunity. A few said their main challenge isn’t selling their branch like it is on the mainland, but finding kids whose English is good enough to pass the ASVAB (Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery), a multiple-choice exam required of all potential enlistees. Most said that unlike the recruiter in the South, the war in Afghanistan isn’t much of a factor.

“If they want that experience, they go with us or Marines,” an Army recruiter said. “If not, they go National Guard or Navy, and can stay close to home. We’re on our own thing, though. I think it’s much different [in the States].”

(On a completely unrelated note: It’s so fucking bizarre young Puerto Ricans serve in the military and salute the American flag but it’s not a state. Jesus Christ. I don’t care that it’s a corporate tax haven. Just make it a state already, for fuck’s sake.)

All this is why recruiters are now trying outreach into long-avoided liberal cities for new service members. All this is why the head of Army Recruiting Command is trying out a “gap year” approach to bored college students looking to do something

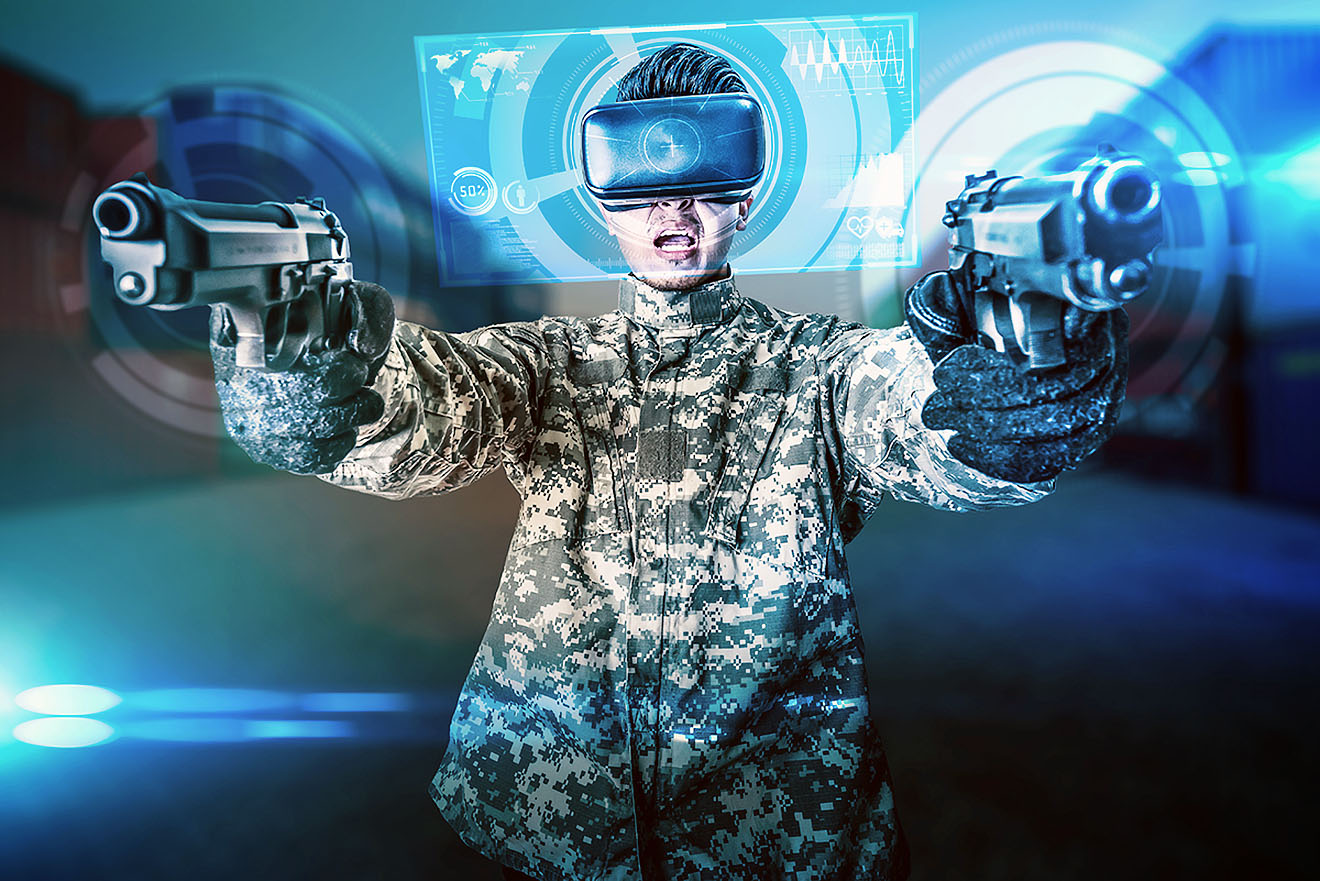

different. All this is why one of the Puerto Rican enlistees I talked to met his recruiter through an online video game tournament — his recruiter’s part of the Army’s e-sports team (yes, it’s a real thing, I couldn’t believe it, either), and started talking up the benefits he’s earned through service between game rounds. I asked the recruit if that’s what he wants to do someday in the Army, if he stays in long enough.

“Sure do,” he said, with the easy shrug of adolescent swagger. “First I got to go to Afghanistan, though. I’m infantry.”

Video games to real combat to video games again. Military recruiting in 2019 in a nutshell.

Matt Gallagher is a U.S. Army veteran of Iraq and the author of the novel “Youngblood” (Atria/Simon & Schuster).