Legendary songwriter Todd Snider battles demons as he chases the perfect song.

There’s this song Todd Snider’s been working on for 30 years now. Call it the white whale of his songwriting career: a crafty, elusive creature, with size, connected to the depths. The search for it—the quest to get the song right—drives him on. It drove him while starting out, when mostly all he had was a dream, and lots to learn, and naysayers to ignore, and nothing gigs in half-empty bars to play. And it kept driving him on through mid-career drug problems, health problems, and relationship problems.

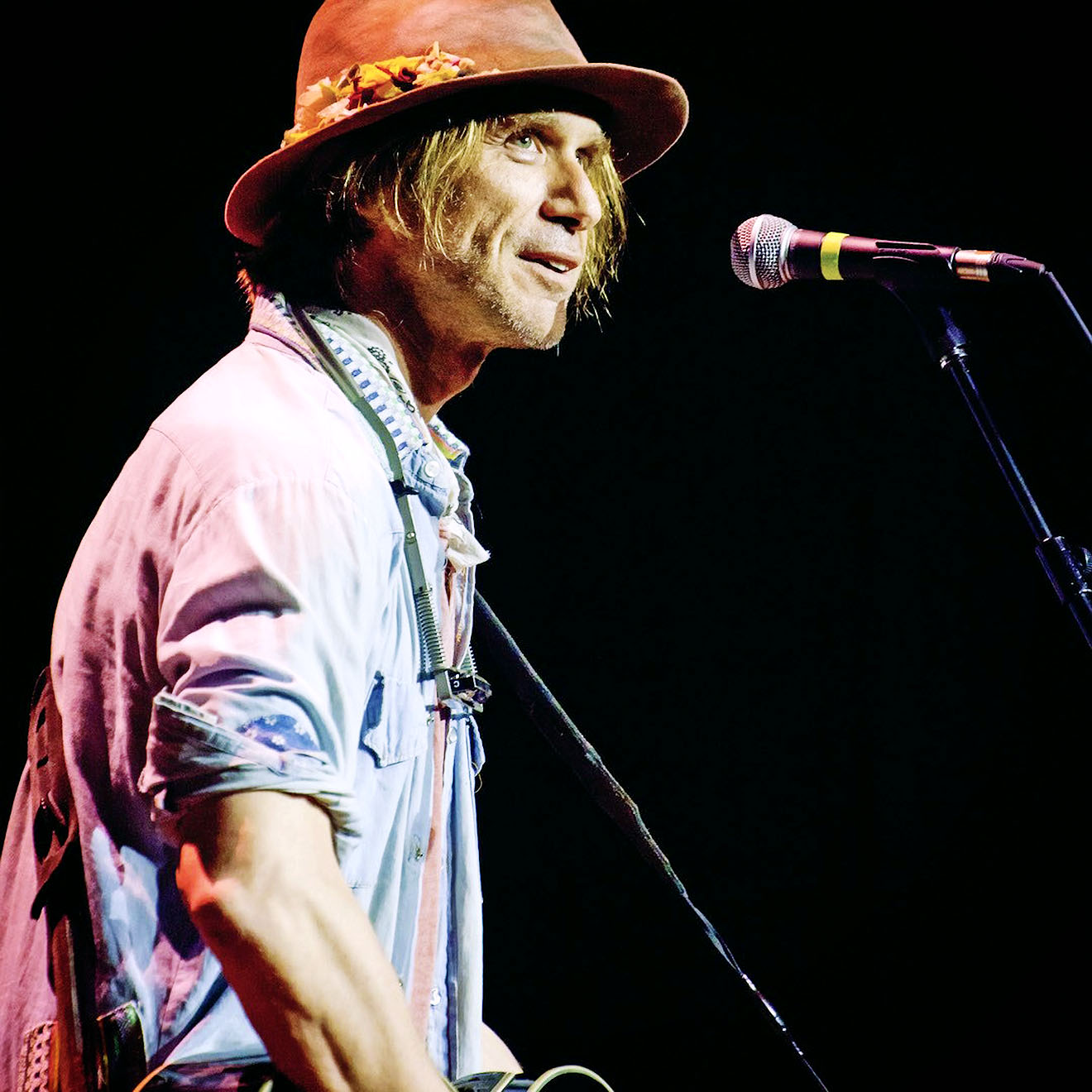

Fifty-two years old now, with shaggy blond hair he might accent with a beard and floppy hat like Neil Young used to wear, Snider has bright, animated blue eyes. He holds your gaze when he talks, telling stories that make you laugh or think. And sometimes, discussing his work, he seems to reengage with the essence of a song right on the spot.

But talking about this one, the song that’s eluded him all these years? Snider shakes his head a little and stares off to the side.

He wrote the first version when he was 22, and called it “Where Will I Go Now That I’m Gone?” Three decades later, it’s a tune that still makes him stare into the distance. Like it’s out there somewhere, the secret to making the song work the way he wants it to. Like if he keeps looking for it, traveling here and there—he’s done a ton of rambling, in the finest folk-troubadour tradition—maybe, just maybe, it’ll appear.

We’re seated at a small kitchenette table inside his tour bus, which is parked behind the historic Wealthy Theatre in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Snider’s faraway look, as he reflects on that just-out-of-reach, spurring-him-on song, comes after a lively 90 minutes of talking to me about politics, drugs, his family, his fans, and life on the road.

That’s the thing with folk singers, Snider says. You don’t even need to ask them a question to start getting answers. But when he gets to talking about music, the focus of his life, he slows down and has an air of searching for something, like a guy on a beach with a metal detector, sweeping the sand, believing he might find an object of value in the very next moment.

A laid-back individual who favors jeans and sneakers, and sometimes performs barefoot, Snider—his fair hair and casual manner suggestive of the late Tom Petty—gets into a marveling mode, even a reverential one, when speaking of times when songwriting can feel magical.

“When you’re letting these sounds that come out of nowhere start guiding your decisions,” he says, “it feels like, Oh my God, there’s a ghost here.”

Speaking of connections to the beyond, a tether through the ether linking the living and those who have passed, there’s a song called “The Ghost of Johnny Cash” on Snider’s new album, Cash Cabin Sessions, Vol. 3, released this spring to much critical praise.

The album’s title nods to the fact that Snider recorded it at Johnny Cash’s old Tennessee hideaway and recording studio, a place still hosting top musicians, and run by Cash’s son, John Carter Cash. Snider first visited in 2015 to watch Loretta Lynn record a couple of songs they’d written together. While there, he had a dream that began to recur.

In the dream, Snider is asleep on the floor in a certain part of the studio, only to be awakened by the Man in Black himself. Cash’s son later told Snider this was the spot where his dad had died, on a bed set up in the studio during the legendary musician’s last days. It wasn’t long after this that Snider returned to record some material for his band Hard Working Americans, a supergroup featuring members of the Chris Robinson Brotherhood and Widespread Panic. And then last autumn, Snider recorded ten spare, acoustic tunes at Cash Cabin Studio. The tracks are heartfelt, moving, funny, and political, with attention given to the craft of songwriting itself, and the songwriter’s life.

On “The Ghost of Johnny Cash,” Snider strums Cash’s beloved, century-old Martin guitar, and sings about Loretta Lynn dancing with Cash’s ghost outside the cabin at night.

Though words like “hippie” and “stoner” have been applied to Snider—a guy who does like his weed, doesn’t carry a wallet, has played in jam bands, and enjoys conversational tangents—he is anything but a slacker when it comes to songwriting. He’s intense, dedicated, studious, and aims high. He says he doesn’t trust a lyric unless it’s been around for a year. Reviewers of this new album have been hailing its songcraft mastery.

The renowned music critic Robert Christgau gave Cash Cabin Sessions an “A,” and wrote on Vice’s music site, Noisey: “You’d never know from its offhand feel how practiced this material is. That’s one reason it’s so replayable…. The other, of course, is that the words are good.”

No Depression put it this way: “Snider is a force of nature. He’s a brilliant songwriter who’s always searching for the next chord, the next story, the next joke, the next idea, the next experience he can turn into song.” Rolling Stone adds, “His lyrics are razor sharp, unsparing, hilarious, and surprisingly tender…. The most provocative moments are topical, when Snider takes scalpels to modern cultural cancers and musical histories both.”

And Folk Radio magazine delivered a rave: “Gripping from start to finish…piercing, precise. Snider’s sterling acoustic guitar work is arguably tighter than ever…. [The album’s] heard as if you are face-to-face with the man, sipping or smoking on something fine, reclining on his porch-side or slumped, quietly contemplating it all in some backroom bar.”

The review conjures a songwriter “spitting blue-collar grit like Springsteen, careening with the same charm of Kristofferson and with the slick wit of [John] Prine, [Randy] Newman, and [Loudon] Wainwright.”

Snider’s productivity and focus are well-known to fellow musicians and others in the music industry, who aren’t fooled by the toker’s drawl. He’s recorded 14 original albums since 1993, released both live and cover albums, appeared on compilations, and made records with other bands. He’s also written a rollicking, laugh-out-loud memoir, I Never Met a Story I Didn’t Like: Mostly True Tall Tales, published in 2014. If he’s not songwriting or recording, he’s touring. He’s played thousands of shows, and the total would be even higher if health and drug issues hadn’t sidelined him at points.

“For [Snider], the clever part of songwriting, that’s the easy part,” fellow songwriter Bobby Bare Jr. once observed to The Austin Chronicle. “That’s the natural part of his talent. But what makes him better than everybody else is how hard he works at the craft of those clever ideas. That’s what great songwriters do. They work hard on what they stumble upon.”

That Folk Radio reviewer is not the only critic to mention Snider in the same breath as some of our songwriting elites. And the East Nashville mainstay has also influenced and helped pave the way for younger, Grammy-winning country stars like Jason Isbell and Kacey Musgraves. On Cash Cabin, Isbell provides harmonies on a terrific track called “Like a Force of Nature.” Isbell and his wife, 37-year-old songwriter and violinist Amanda Shires, also contribute backup vocals on two of the political songs, “The Blues on Banjo” and “A Timeless Response to Current Events.” Rootsy, pointed, and conversational, “Blues” calls out NRA-beholden politicians and border-wall hysteria, while “Timeless” takes on phony, divisive patriotism.

Like Snider, Isbell and Shires have decided ignoring politics isn’t an option, not in the current climate. Younger Nashville musicians of a progressive bent can look to Snider for an example of a veteran musician who’s found a way to give compelling voice to his political convictions without sacrificing musicianship—like a latter-day Woody Guthrie.

He’s keeping a close eye on what’s going on, politically and culturally. When we meet on his tour bus, he’s got the TV tuned to CNN, makes reference to the politics of Meghan McCain, and criticizes the “prison-industrial complex.”

But of course what most often catches the attention of fans and musicians (count comedian Richard Lewis among the former; Lewis, a Snider friend, gets a mention on this new album) is his musical prowess and creativity—his deft way with a song. Snider took up the craft of songwriting in his late teens, when music put a hex on him. That hex is still as strong as ever. An hour before his sold-out show in Grand Rapids, he can’t quit thinking about that damn elusive song, the one whose final form he seems doomed to forever chase.

“It’s the worst problem I’ve ever had,” Snider says, shaking his head again. “That’s the thing. You just keep looking for it. I don’t even know what it is.”

Inside the 400-seat theater, the lights dim and Snider comes onto the stage, a mile-wide grin on his face, raised hands making peace signs. A crowd of mostly middle-aged fans rises and applauds. After getting ready to play, Snider nods hello and begins to strum and sing. Moments later he backs away from the mike, and you can hear him chuckle in disbelief as the crowd continues singing his song louder than he was singing it.

Later on, there’s a moment of magic as everybody in the theater who can whistle does so in unison, right along with Snider. And then there’s the interlude when his brown-and-black dog, Cowboy Jim, a fan favorite who’d wandered onstage earlier, comes back out and starts barking in seeming agreement as Snider sings a line about an old radio station that carries veiled social commentary: “We used to listen then.”

Intimate accidents like the crowd turning into a whistling chorus, or Cowboy Jim’s perfectly timed woofs, which sent a delighted charge through the theater, are the kinds of things that have kept Snider hooked on performing music his whole adult life.

“I get goosebumps just thinking about it,” Snider tells me later, using the words “electric” and “cosmic” to characterize those moments of sudden communal harmony. “You’re part of this gig and you feel like you’re part of this bigger thing. It’s like God wanted it to happen. So, it’s like, Let’s drive another six hours and do it again!”

THOUGH in person, in his book, and in his music over the years, Snider has never had a problem discussing his life’s journey, which has seen its share of ups and downs, he chose to limit the autobiographical stuff on this new album. Half the songs address societal and political matters, while three more explore music-making itself, and Nashville musical history. Had he wanted to mine his recent life for material, there would have been a lot to consider. He got divorced in 2014. He also started abusing painkillers, a habit that began when he developed a back problem. He spent too many days in a narcotic haze, and missed some shows. But he’s feeling a lot better now, and says weed’s all he needs.

His new record doesn’t touch much on his divorce, despite its impact on his life the past few years. Snider doesn’t really see the point, he tells me, in those “bummed about a girl” musical laments. “Sometimes I think those songs get so whiny,” the songwriter continues. He believes “Like a Force of Nature” says enough about what he’s been through, and says it in the right way.

Wise, moving, and unsentimental, this tune, with perfect phrasing and subtle wit, opens, “Well, if we never get together again/ Forgive me for the fool I’ve been/ See if you can remember me/ When I was listening to my better angels.” The narrator then confesses to a need for constant motion, an urge so strong it’s like a force of nature.

“I can’t keep myself from moving,” Snider sings, his tone weathered, a voice with mileage on it. As it happens, the songwriter himself, he estimates, has lived in 50-plus residences, to go with decades of cross-country touring.

When it comes to the early part of his roaming life, biographical accounts tend to vary a bit, as Snider’s story has acquired some romantic lore over the years, troubadour tales taking on lives of their own. But a teenage relocation is a constant in the different accounts. Born in Portland, Oregon, Snider moved from suburban Beaverton to Austin, Texas, in his teens. His parents had gone broke, and his older brother had found work in Austin, which helped motivate the change of scene.

While growing up, Snider found his dad a mysterious figure. He says his family had money for a while, and then suddenly lost it all. Later, his parents got divorced.

“I think my dad did a lot of coke and was gambling,” Snider tells me. “He was a wild fucker.” Snider says he never knew exactly what his dad did for a living, but it was construction-related. He describes his late father, Danny, who died at 54, as “tough.”

Years ago, Snider heard rumors that his dad had a hand in organized crime—a theory buttressed both by an Oregon reporter, who once told the songwriter as much, and by the fact that a family friend eventually got murdered in a hit. Snider says he doesn’t doubt the rumors about his dad, but he can’t say for sure if they’re true.

Early on, Danny Snider made it clear he didn’t approve of his son’s career choice. He told the aspiring songwriter that if he didn’t drop the music dream and find a real job, he’d spend his life playing the same shitty bars for the same shitty pay. A conservative Republican, Danny didn’t find songwriting a reputable profession, didn’t share his son’s love of poetry, and distrusted the politics of folkies who strum guitars and pen lyrics about life, love, planet Earth, and social injustice. During his early twenties, Todd would get in heated political arguments with his dad. When the musician would accuse right-wingers of racism and homophobia, Danny would come back and call his son a fag.

As a young man starting out in music, Snider found himself looking beyond his dad for support and inspiration. With his personality and talent a combination that could get him noticed, he had the good fortune of finding father figures who also happened to be some of the country’s best songwriters. One of those was Jerry Jeff Walker, who wrote “Mr. Bojangles.” Snider has said seeing Walker play solo at an Austin bar helped show him the way: Instead of running around trying to get a band together, he could just be a man with songs and a guitar.

After sending a demo tape to Memphis singer-songwriter Keith Sykes, a friend of both Walker and John Prine, as well as a member of Jimmy Buffett’s Coral Reefer Band, Snider was encouraged by Sykes to move to Memphis and join the thriving music scene there.

Eventually, Snider snagged a regular gig at a club called the Daily Planet. Meanwhile, Sykes was doing what he could to help Snider launch his career. The songcraft education that began in Austin—how to chart rhyming patterns, for example—accelerated in Memphis. Snider was learning from Walker, Sykes, Prine. And from Jimmy Buffett himself he gleaned a few parlor tricks when it comes to working a crowd.

From all these guys he also learned how to grind, Snider tells me. With their stories of starting out, and from his observations of these mentors in action, he got an idea of what it takes to succeed. It might mean playing nightly shows to 15 or 20 people for who knows how long. And it definitely means working on a song until it’s perfect. Even if it takes 30 years.

In 1993, Buffett signed Snider to his Margaritaville Records label. Danny was there the night his son put his signature to a contract for his debut album, Songs for the Daily Planet, released that year. Seeing tangible signs of his son’s music success impacted the elder Snider. “I remember that night felt like show business,” Snider recalls. “Like something a dad could get. He was like, ‘I’m really proud of you. You’re working hard.’”

Danny Snider died less than a year later.

FOR years, Todd Snider assumed he’d die in some sort of accident. A car crash. A tour prank gone wrong. He’d think of Elvis dying on the can. Buddy Holly in a plane crash. Janis Joplin’s heroin overdose. He says his mom, Micki, was always worried about him. She still worries. And his dad worried, too, but more about his son’s financial and marital prospects.

Truth be told, with all the drugs Snider has taken, he has flirted with death. And in 2016, he says he started regularly taking acid to go with the pills, drinking, and heavy marijuana use.

Snider was scheduled to play a music festival in Chillicothe, Illinois, but collapsed and had a seizure before taking the stage. His manager, Brian Kincaid, helped carry him unconscious to the medical tent. An ambulance arrived. Snider remembers coming to en route to the hospital. Kincaid remembers Snider waking up and promptly laughing as a young paramedic kept missing Snider’s veins with the IV needle—the result of a fast, bumpy ride and Snider’s inability to remain still. “I was tripping balls,” Snider laughs. “I was talking to him like, ‘Well, it’s me and you, kid! This is going to be a weird way to go.’”

Miraculously, Snider recovered enough to play a gig the next night in Nashville. Doctors had flushed him out with fluids overnight and through the morning. With Kincaid’s help, they got him on the bus and drove as fast as they could to Music City. Years ago, Snider might have skipped the show, he says. In his younger, wilder days, there were times when he was getting busy with a girl, or simply got too wasted to perform. “There’d be maybe 300 angry people somewhere and none of them would sue me,” Snider says. “I’ve been really good about it in the past few years, though.”

Last year, he did have to cancel some tour dates for medical reasons. He suffers from chronic back pain and has arthritis in his neck. While explaining how hard it is for musicians to stay in shape and routinely see a doctor, Snider points to the left side of his neck. He says a doctor found a trio of discs scraping into each other. His fans—especially the ones Snider’s age or older—are understanding when his spine problems cause cancellations, and send him well wishes, or share their own tales of chronic pain.

He’s trying to live right these days—or right enough. Snider hopes missing gigs—for any reason, but especially because of drugs—is a problem in the rearview mirror. He doesn’t want fans to ever again have to post things like this 2017 comment after some shows were dropped: “This is nothing new for Todd. [You] never know if he’s going to play an awesome show, nod off and walk out mid-set, or not even play at all.” Other fans posted about how unwell he looked. Suspecting it was “not going to be a good ending” for Snider, one commenter wrote, “Shall we predict his death?”

Snider says life and death have been on his mind recently, in part because his dad died so young. He talks to his brother Mike about this. Mike’s 54, the age their father died.

INSIDE the Wealthy Theatre that night in Grand Rapids, Snider gets big laughs talking about his weed-fueled adventures. He mentions how, at Cash Cabin Studio, he got so high he wandered the surrounding forest for hours to “find a song.”

A fantastic storyteller, with a gift for comic confessions and candid recollections, Snider keeps fans as entertained between songs as he does during songs. With me on the tour bus, he shared tales of epic acid benders he says lasted for days. And just as he does in the theater, on the tour bus he spoke of the importance of persistence, of how he built his career through years of staying at it, never giving up. “It all just slowly works,” he said. “I’ve never had a hit, but I’ve got like a million albums, and you just keep plugging away.”

That night in Michigan, Snider abandons his set list early, letting the crowd and their shouted preferences guide what he plays. Eventually, he lets everyone know it’s time for a last song, and starts softly strumming the opening chords to “Working on a Song.” It’s a tune from the new album, inspired by that song he’s chasing.

“I never gave up on it,” Snider tells the crowd. “I always thought…I’ll get this one day, you know?” A hush descends inside the theater as he begins to play.

“When that idea first came to me, I was only 22,” Snider sings, more slowly than usual. “By 25, I had realized it was all that I could do/ To make it to the end, but then again, I always knew/ If I never got it finished I could die trying to.”

If Snider’s addictions have nearly killed him, the place where he stands now, that stage in Grand Rapids, gives him life. And being hooked on the art of words and music, an art that helps make his *pain vanish and helps others forget their own pain—that kind of addiction’s all right, if not always easy.

When Snider talks to me about that quest song, one he’s shaped into at least ten versions and tried to cowrite with other top songwriters, including Kix Brooks and the late Susanna Clark, he says it means something different to him now.

“It’s about what am I going to do when I don’t sing anymore,” he says, looking down at a Sharpie pen he’s twisting back and forth in his hands. “I get why Willie [Nelson] plays every night. I didn’t used to, but now I do. I don’t want to finish my songs. I don’t want my show to get over. I’m not going to freak out about dying, but I enjoy being here.”

Up on the stage, Snider sings, “They said maybe you’ve been chasing a song too long/ It’s turned into a song about a song you’re working on/ I mean it’s gone, man, come on, let it go/ But you know, giving up a dream is just like making one come true/ It’s easy to sit around talking about, it’s harder to go out and do.”

The 52-year-old performer slows down on the guitar, then strums his final chords. The theater lights fade. Showered in the adoration of a standing ovation, Snider sets down his guitar, slides his hands into his pockets, nods “thanks,” and walks off the stage.

Sean Neumann is a Chicago-based journalist and musician who spends much of the year touring with his bands. His writing on politics, sports, and television has appeared in Rolling Stone, ESPN, VICE, and more. Follow him on Twitter @neumannthehuman.