A Creedence Clearwater Revival classic turns 50.

When director John Landis and his music team needed a song to score two minutes of screen time just before their film’s protagonist, American backpacker David Kessler, grows a pelt of black body hair, deadly fangs, and vicious claws, they turned to “Bad Moon Rising,” a 1969 Creedence Clearwater Revival song written by John Fogerty.

The movie? An American Werewolf in London, a now-canonical 1981 horror-comedy that makes darkly humorous use of popular songs throughout. Van Morrison’s “Moondance” scores a sex scene, and versions of “Blue Moon,” sung by Bobby Vinton and Sam Cooke, appear, too. But the CCR song is a high point, ushering in the famous werewolf transformation scene, and Landis would later say “Bad Moon Rising,” with its ominous lyrics joining a sprightly tempo and catchy riffs, fit the “mood” of his hybrid movie.

As it happens, a spooky Hollywood film was central to Fogerty’s inspiration. If the song’s name came from a little book of scribbled title ideas he’d been keeping since 1967, it was a movie released in 1941, a few weeks before Pearl Harbor, that got Fogerty going lyrically. Eventually called The Devil and Daniel Webster, the film was based on a short story of the same name by Stephen Vincent Benét, and published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1936, during the depths of the Depression.

In Benét’s story, a New Hampshire farmer named Jabez Stone sells his soul to the devil for cash to overcome his debts, then enjoys a stratospheric rise to local power before the Dark Lord arrives to collect and Webster has to intervene and defend the farmer at trial.

“[His] crops were the envy of the neighbourhood,” Benét writes of Stone’s rising fortunes, “and lightning might strike all over the valley, but it wouldn’t strike his barn.” In the movie, we see dark, distant clouds, followed by destroyed fields. “But not my wheat!” shouts James Craig, who plays Stone. “I’ll have a rich harvest!”

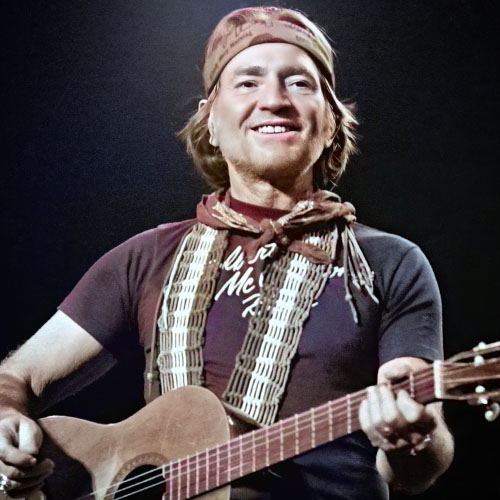

John Fogerty saw the movie on TV when he was young. Born in 1945, Fogerty and his bandmates in Creedence Clearwater Revival were classic suburban California kids, raised in El Cerrito, on the east side of San Francisco Bay, during the early days of television. In the late sixties, after ten years hustling the band through various names and styles, they finally had the attention of radio listeners.

The singles “Suzie Q” and “Proud Mary” had sold well, and Fogerty was becoming more productive as a writer. He composed songs in near-silence while his wife and young children slept at night. In that unlikely laboratory—quiet and domestic, even while the greater American culture resembled a powder keg, with both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy assassinated just months earlier—Fogerty remembered the old black-and-white movie and start putting words to chords and a melody.

In 1993, speaking to Rolling Stone, he highlighted a post-storm sequence in the movie: “Everybody’s crops [are] destroyed. Boom. Right next door is the guy’s field who made the deal with the devil, and his corn is still straight up, six feet. That image was in my mind. I went, ‘Holy mackerel!’”

And so, taking inspiration from a subdued, 15-second scene in a 1941 movie, John Fogerty wrote some of the most nightmarish lyrics to ever appear in a Top 40 radio hit: “I hear hurricanes a-blowing/ I know the end is coming soon/ I fear rivers overflowing/ I hear the voice of rage and ruin.”

It may not be the archetypal Creedence song, this tune which climbed to No. 2 in America and topped the U.K. charts. “Fortunate Son” is truer to their sound and energy, “Down on the Corner” is easier to dance to, and no riff, by anyone, has ever bettered “Up Around the Bend.”

Nevertheless, “Bad Moon Rising” embodies everything that made Creedence great. It has its own marvelous intro hook, soon supplemented by the band’s perennially underappreciated rhythm section: Doug “Cosmo” Clifford on drums, Stu Cook on bass, and Tom Fogerty, John’s older brother and the group’s painfully deposed onetime frontman, on rhythm guitar. It’s also a vintage John Fogerty production, an audio tribute to Sun Records’ slap-back stomp. Despite its dark lyrics, it’s just so fun.

Fogerty never wrote love songs, and contrary to Creedence’s ubiquity in Vietnam-era-set movies, he didn’t regularly channel his songwriting gifts into political-protest anthems or social-minded songs, either. “Bad Moon Rising,” like “Up Around the Bend,” “Run Through the Jungle,” and so many others, is mostly a litany of images, a summoning of a mood. In this case, the mood is literally apocalyptic, even though the tune and beat are as bouncy as the band ever got.

Perhaps that bounce helps account for the song’s strikingly durable legacy, even by Creedence standards.

It’s been covered by 20-plus artists, in multiple musical styles, including reggae. It’s appeared in two dozen films and TV shows, from Blade to The Big Lebowski, from Mr. Woodcock to Kong: Skull Island, from The Walking Dead to Alvin and the Chipmunks. In Argentina, it’s used as a stadium soccer chant. And it’s the subject of the most famous misheard-lyric joke this side of “Purple Haze.” People frequently interpret the chorus’s closing line, “There’s a bad moon on the rise,” as “There’s a bathroom on the right.” Fogerty occasionally lightens up his own song by singing that blooper lyric in concert.

Then there’s Sonic Youth, a defiantly un-Creedence-like postpunk noise band who took much harsher stands on social issues and specific politicians, including Ronald Reagan, when they first emerged from the early-1980s New York underground. Their second album, released in 1985, is their angriest and darkest, almost devoid of melody, and filled with impressionistic lyrics about Native American genocide. The record’s title? Bad Moon Rising.

(CCR trivia: They were the first band to mention “Ol’ Ronnie,” as they called him, in a rock song. He’s in verse three of “It Came Out of the Sky,” from Willy and the Poor Boys, released in 1969.)

“Bad Moon Rising” still floats amiably through our culture, enriching road trips, cover bands’ setlists, and classic-rock radio programming. It has amassed numerous cultural reference points over the years, in part because it emerged from so many references itself. A river of storytelling, stretching from Goethe’s Faust to the Saturday Evening Post to Hollywood, flowed through “Bad Moon Rising” before Creedence ever recorded it, following days working the song out in Doug Clifford’s back-garden shed.

Since 1969, it’s picked up the Coen brothers, Manhattan art rock, jokebook mentions, horror movies, and so much more. Let’s assume it will continue to

echo, inspire, and create cultural linkages, growing like Jabez Stone’s corn, reference-wise. After all, in “Bad Moon Rising,” the storm never arrives.

John Lingan is the author of “Homeplace: A Southern Town, a Country Legend, and the Last Days of a Mountaintop Honky-Tonk.” He lives in Maryland with his wife and two children, and is writing a biography of Creedence Clearwater Revival for Da Capo Press.