Do I have to like Captain Beefheart?

I’m no art historian, but it strikes me that the “art” of modern art takes place at some point after its creation. You paint a skyscraper-size donut, say, and then spend years talking about it: what it symbolizes, how it comments on what came before it, what it’s trying to say.

Successive modern movements upended the traditional “pretty picture” aesthetic established during the Renaissance, and in the process traditional formal skills became irrelevant. It’s all about the concept.

But in popular music, it wasn’t that simple. Ornette Coleman brought an avant-garde approach to jazz music, and at the time people thought he was just playing out of tune. Why the difference?

Unlike visual art, it takes time to listen to avant-garde music. And when so much music is so awful, how likely is it that the awful thing you’re listening to is awful for a reason? Like the giant donut, can you come to appreciate a piece of music just by talking about it?

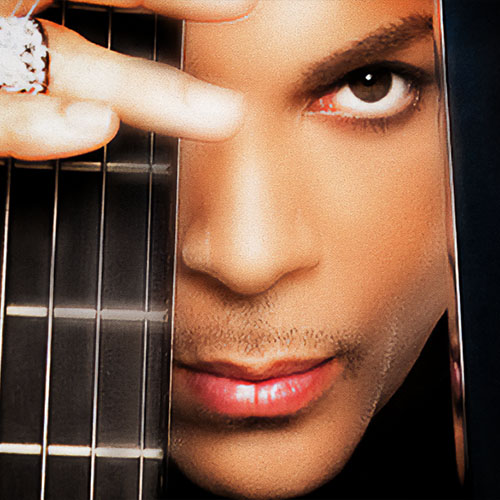

Consider the 1969 album Trout Mask Replica by Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band. This record has legions of fans, a thing I know because at least 10,000 of them have tried to get me to listen to it. To the untrained ear, it’s the sound of stoned teenagers in a garage, not actually playing together but all playing different songs as they tune up or try out different amp settings. On top of that racket, there’s a guy spewing half-funny beat poetry in a near-perfect imitation of blues icon Howlin’ Wolf. So what makes it art?

Captain Beefheart (real name Don Van Vliet) recruited musicians with the idea to live the material, which meant communing in a small house outside Los Angeles for eight months and blocking out everything else. But what started as a hippiefied attempt at deep expression quickly turned into a hostage situation, later described by drummer John French as “Mansonesque.”

With no money, the band ate cold beans out of cans and took turns sleeping in various corners on the floor. They suffered constant emotional and physical abuse by Van Vliet, who demanded loyalty and ostracized those who questioned him. Straight out of the cult-leader playbook, he broke their wills by keeping them hungry and exhausted.

Van Vliet wrote melodies on the piano, an instrument he couldn’t play, that were then transcribed by John French for the band. Not knowing anything about keys or time signatures, Van Vliet assembled compositions bound together only by the paper they were written on. Thus you can hear, in just the first track, more than twenty melodic motifs in various keys and time signatures, stacked on top of each other.

But what sounds like chaos is actually an incredibly precise matrix of themes bound together by impossibly skillful musicians. With modern technology, it would be easy to overdub or program these parts, but they didn’t do that.

Captives of a megalomaniac, the band rehearsed for fourteen hours a day for eight months and their performance was recorded live. If they did the whole thing again, it would sound exactly the same.

Knowing this, when I hear the record, well… I still don’t like it. But in an art-historical sense, and considering the plight of those poor musicians, it’s hard not to stand in awe of it — kind of like the Pyramids, which were also created by slaves.