“I consider myself a normal person,” says Andrew Dodge, 28, whose line of work involves visiting convicted murderers, writing to serial killers, and selling artifacts in some way associated with the world’s most twisted souls. “I’m a small-town guy,” the Washington State native continues, “who just happens to befriend infamous criminals.”

One of America’s leading “Murderabilia” dealers, selling homicide-linked collectibles from his online store, TrueCrimeAuctionHouse.com, Dodge does cop to a fascination with sociopathic minds — especially the minds of killers who acquire a macabre celebrity for their shocking acts. And he adds, “Anyone who knows me knows I have a very dark sense of humor. Every day is like Halloween for me.”

A level of comfort with darkness is not only an asset, given his business, but a necessity. Dodge travels to meet with prisoners on death row. He speaks by phone to multiple murderers weekly. Then there’s his website, where you can purchase Charles Manson’s clipped hair in a glassine bag, a hand tracing from Richard “The Night Stalker” Ramirez, and an autographed work of art by Dennis Rader, aka the BTK Strangler.

Those looking for an item connected to serial killer Ted Bundy will find a scrap of plastic from one of the green trash bags Utah police recovered from Bundy’s tan VW Bug in 1975—part of Bundy’s “murder kit,” which included handcuffs, an ice pick, a crowbar, gloves, a ski mask, and a mask made from pantyhose.

Some of the goods have an eerie normalcy, like a handwritten recipe for chili con carne from Arthur Shawcross, who killed at least 13 people in upstate New York.

Other tokens include prison letters, autographs, postcards, jail-cell books, goatee and pubic hair clippings, bloody handprints, a playing card signed by Henry Hill (the mobster turned informant played by Ray Liotta in Goodfellas), a San Quentin death-row hot pot signed by Richard Allen Davis, who kidnapped and killed 12-year-old Polly Klaas, and an anthology of haiku poetry that Rader once had inside his Kansas prison cell.

Remember the 2003 Macaulay Culkin movie, Party Monster? It tells the story of Michael Alig, a flamboyant Manhattan party promoter who murdered and dismembered a friend and fellow drug addict in 1996, before dumping body parts in the Hudson River. Dodge’s site offers an Alig foot tracing and a signed copy of the killer’s Wikipedia page.

Each item listed on the site features an enlargeable photograph, additional images, and an information-packed column summarizing the relevant criminal’s life and dark deeds, along with a description of the item’s origin.

In the “Books” category, there’s a 1971 paperback called None Dare Call It A Conspiracy, a best seller pushing the idea of a “New World Order”—a secret society of wealthy elites trying to spread a global socialist government—that once belonged to David “Son of Sam” Berkowitz, who killed six New Yorkers by handgun between the summers of 1976 and 1977.

While Shawcross’s recipe costs just $50, the Berkowitz book, which contains his handwritten marginal notes, goes for $1,666, making it one of the site’s pricier items.

The book’s webpage notes that Berkowitz’s notoriety led to New York State enacting so-called “Son of Sam” laws, which bar criminals from monetizing their fame. It adds:

“The book was owned by Berkowitz in prison. Accompanied is a handwritten letter signed by Dee Channel, Berkowitz’s infamous pen pal. Included is the original envelope the book was sent to Dee in. The envelope return address is signed, Berkowitz.”

Visiting Dodge’s store is like taking a comprehensive, intimate tour of America’s top homicides in the past 40-plus years. All the big-name killers are here, represented by at least one item, from John Wayne Gacy to O. J. Simpson (okay, accused killer), and from Aileen Wuornos (played by Charlize Theron in 2003’s Monster) to Scott Peterson, convicted of killing his pregnant wife, Laci, in Modesto, California, in 2002.

Items linked to murderous terrorists, such as those involved in the Boston Marathon and Oklahoma City bombings, appear, too.

Terry Nichols, who conspired with Timothy McVeigh in the 1995 Oklahoma massacre, mailed a religious book, Things That Differ, last July, and now it can be yours for $185. It was sent from the Florence, Colorado, supermax prison where Nichols occupies “Bombers Row” alongside Olympic Park terrorist Eric Rudolph and Ted “The Unabomber” Kaczynski. Opposite the title page, Nichols neatly wrote, “I hope you find this enjoyable, informative, and enlightening. Blessings, Terry.”

Taking in the letters and books, the cookware and music CDs, we’re reminded that these killers, their crimes ghastly, their sociopathy extreme, are, or were, members of our species, no matter how much we wish they weren’t. We call them “monsters,” understandably—see the aforementioned movie titles—but Dodge’s shop, crowded with humdrum human objects, makes it harder to view these individuals as unrecognizably alien.

It’s an awareness most sharply present when looking at the photos and letters. We encounter future killers in snapshots taken by friends or family. Sarah Kolb, who strangled and dismembered a high-school classmate in 2005, is shown posing with two golden retrievers. On the photo’s flip side, Kolb wrote the dogs’ names: Kye and Abby.

John Robinson, sometimes called the “internet’s first serial killer” for making online contact with victims beginning in 1993, was convicted of three murders, admitted to five more, and might have killed others. In the “Photographs” section, we see a grinning, grade-school Boy Scout shaking hands with a fellow Scout.

Enlarge the letters and you can read them. Again, many are striking in their normalcy. If the info page didn’t detail the horrific murders, you wouldn’t guess the words were penned by a homicidal sadist. Some of the killers write clearly, even elegantly, and express normal human emotions (whether genuine or feigned).

“The holiday card you sent was cool,” writes Richard Ramirez. “How’s the new neighborhood? Made any new friends? I hope you’re feeling better.”

A typed, six-page letter from John Wayne Gacy quickly gets less “normal,” though, as he starts manipulating, lying, simmering with controlled rage, and graphically discussing sex.

A handwritten Manson letter, priced at $350, is jagged of style and thought, has a few cross-outs, and includes a swastika. But, on balance, the letters were not written in the extreme state of mind these killers presumably entered when committing their crimes.

In the “Female Killers” section, some of the convicts write bubbly, unguarded missives, using exclamation points, all caps, and even heart-dotted i’s.

BUT what about those face-to-face interactions Dodge has with killers, separated by safety-glass partitions? Dodge says one murderer he’s met stands out from the others.

“I’ve only been truly scared twice while visiting an inmate,” the true-crime collector reveals, “and both times it was with the same individual.”

The first encounter was in November 2017, and the setting was one of the death-row buildings at the Allan B. Polunsky Unit in the boondocks of southeast Texas. Polunsky is a grim, sprawling complex of gray concrete buildings on 470 acres of unincorporated land. It’s surrounded by high-security fencing topped with razor wire, and guards surveil the 23-structure complex from a quartet of watchtowers 24-7. Dodge won’t name the inmate, one of roughly 300 at any given time in this wing of Polunsky, where the prisoners wear white jumpsuits with “DR” on the back, and live in slit-windowed cells of 60 square feet.

The eight-year veteran of the murderabilia circuit has a rule concerning discussion of killers: He’ll only go into detail about those who have died, or those he no longer communicates with. Depending on the convict, he may not even identify them by name. But he will say this about the Polunsky inmate:

“His crimes were shocking, grotesque, stomach-wrenching.”

In the movies, the most famous visit to a serial killer is when FBI Academy trainee Clarice Starling, played by Jodie Foster, visits Hannibal Lecter, played by Anthony Hopkins, in The Silence of the Lambs. Lecter utters his celebrated line at the end of the unnerving encounter: “A census taker once tried to test me. I ate his liver with fava beans and a nice Chianti.”

In that scene, Starling walks down a dim corridor between barred cells. One inmate creepily stares. Another says something crude. Even before she reaches Lecter, it’s scary.

During Dodge’s Polunsky visit, he removed his shoes, went through a metal detector, and got patted down by a correctional officer, who looked at him sideways for wanting to visit this death-row inmate. He was then escorted into a visitors’ room, where he watched the clock, waiting. He had no idea what to expect from the guy. Dodge says the fear wasn’t there right away. But he felt a heaviness in his soul from the place’s grimness.

Finally, the jumpsuited inmate arrived. He began talking about his murders. Dodge had listened to killers discuss their acts before. And he’d been reading about murders for years. But this experience was different, he says. This guy got granular, and his crimes were horrific. “What made matters worse,” Dodge says, “was that the individual was not only bragging, but smiling the entire time as he relived his crimes, discussing everything in detail. I didn’t feel physically scared. The conditions in the room were safe. But I felt emotional and mental fear, listening to him. I was almost in a state of paralysis.”

This didn’t stop Dodge from visiting the inmate a second time. And once again, the man began to brag and smile as he went back over the details of his gruesome murders.

AS Dodge points out, there are two questions people tend to ask when they learn what he does for a living. How’d you get into this? is one. The other question raises the issue of “blood money”—the ethics of making money selling items connected to these brutal crimes. Sometimes, Dodge says, people suggest what he does isn’t right.

In response, the collector counters, “I’m not hurting anybody with what I do. I don’t find it any different than what the media and Hollywood does with true-crime content, and always has. And I’m on a tiny molecule scale compared to what they do.”

It’s hard to argue Dodge’s point about the monetizing of murder. True-crime material is everywhere you look, whether on television (Dateline NBC, 48 Hours, Making A Murderer), in movies (Zodiac, My Friend Dahmer, Monster), or in books.

Consider In Cold Blood, Truman Capote’s 1966 literary masterpiece about the murder of a Kansas family in 1959, and Vincent Bugliosi’s book Helter Skelter, about the Manson murders, published in 1974. These are the world’s top-selling true-crime narratives, with millions of copies printed. Both came out shortly after the crimes, with relatives of the victims still grieving. And they made a lot of money for two New York publishers, and two authors.

Tabloid newspapers like the New York Post run wild with murder stories—especially the marquee ones, such as the JonBenét Ramsey case, or that of O. J. Simpson. (Side note: Dodge’s site does have Simpson items for sale, including his Citgo Plus credit card.)

True crime has been a hot genre for a while, of course. Ann Rule’s best-selling 1980 book about Ted Bundy, The Stranger Beside Me, sold millions, and Rule followed it up with a number of other best sellers, while spawning dozens of imitators. These days, however, story-delivery venues have multiplied, from Netflix to podcasts, and they’re monetizing more true-crime material than ever. Serial, S-Town, and My Favorite Murder are three of the top podcasts in the last few years, and all three work the true-crime genre.

Murder sells. Serial killers can acquire a name-recognition factor rivaling celebrities in sports and movies. In terms of monetizing homicides, where do you draw the line? Does Dodge cross it?

His website’s tone is sober. It’s a well-designed site, but it’s not slick, or sensationalistic. It doesn’t come off as romanticizing or elevating these sociopaths. And it’s not like Dodge is getting rich off his enterprise. He says his platform receives up to 150,000 unique views weekly, but the attention doesn’t convert to huge sales, with most of the visitors just browsing.

“I’m not one who glamorizes what they do,” Dodge says simply. “These killers are grotesque, they are unforgivable. I find comfort in knowing they are locked up. But I am also aware there are others like them on the loose, which is terrifying. Law enforcement believes at any given time there are 25 to 50 active American serial killers.”

Dodge uses terms like “artifacts,” “preservation,” and “dark history” when discussing his site. While other people might get nerdy about vinyl records, Civil War battles, wine vintages, or the etymology of words, Dodge is driven to collect and catalog material shadowed by homicide, soaked with blood. He wants to get close to these objects—close enough to touch.

“I enjoy the dark history part of it,” he says. “Murder will always happen, violent death will always be around us, and I choose to embrace and understand death, rather than fear every single thing around the corner. I believe in preserving this dark material, for historical purposes, and for the fascination, the curiosity, we have about these crimes.”

ANDREW Dodge was 11 when his own fascination began. That was when he learned about the Milwaukee chocolate-factory worker turned cannibal, Jeffrey Dahmer.

People have asked Dodge if there was some horror in his own childhood that might account for the way he gravitates toward darkness, but he says his childhood was normal, though he did, like a lot of kids, weather a parental divorce. And like a lot of teenagers, he acted out in high school, and eventually dropped out. He ended up getting his GED, and later received a two-year degree in Human Services.

Jeffrey Dahmer’s story kindled an early interest in murderers, but it wasn’t until 2010, at age 19, that Dodge first wrote a letter to a jailed serial killer, Phillip Jablonski, with whom he still corresponds.

Between 1978 and 1991, Jablonski killed five women, with four of the murders coming after he was paroled following 12 years in prison for the 1978 murder of his girlfriend. During his first incarceration, a woman responded to Jablonski’s newspaper ad and they ended up getting married. This woman was one of those he killed in 1991 during a five-day murder spree. His actions included stabbing, strangling, raping, mutilating, and shooting. Behind bars at San Quentin, Jablonski is currently one of 2,600-plus prisoners on death row nationwide.

During the period when Dodge first contacted Jablonski (a convict known, in fact, for his prison letter-writing), he had been watching a lot of movies, documentaries, and TV shows about serial murderers, and decided to reach out to one. The impetus, he explains, was to gain a little understanding, if possible, into what makes these killers tick.

This quest to illuminate, in any way, behavior unfathomable to most of us continues to fuel Dodge’s collecting and outreach efforts. He is especially struck by the way psychopaths can commit the most obscene homicides and then, in some cases, come home to a wife and kids and eat a sandwich. He says holding a letter written by Ted Bundy or Aileen Wuornos gives a chilly thrill. But to him, it also feels like this spooky intimacy delivers a small insight into the killers. Most important of all, Dodge says, possessing these objects—taking murder tokens in hand—gives him an experience of getting close to evil, without risk to his safety. Nobody wants a serial killer at their front door. His business brings him close to his enduring fascination, without the dangerous consequences.

SO how does he go about contacting killers?

“I usually do a little bit of research first,” Dodge says. That includes going into Department of Corrections databases and digging up basic inmate information. Sometimes he’ll call a prison to track down a detail. Then he writes a letter of introduction. He asks how the inmate is doing, and says a few things about his hobbies and “real-life stuff like food, politics, news, TV.” Sometimes an inmate contacts him first, rather than the other way around.

“A lot of them just want somebody who isn’t on the inside to talk to,” he says.

Dodge has now corresponded with more than 250 inmates. He’s traveled to multiple penitentiaries for visits, and has sat down with four death-row prisoners and counting. Among the killers he has visited is David Conley, who massacred eight people in August, 2015, in Houston, six of them children, one of the kids his own 13-year-old son.

Serial killers David Berkowitz, Wayne Williams, and Derrick Todd Lee; Mikhail Markhasev (killer of Bill Cosby’s only son, Ennis); Manson family member Bruce Davis; and Boston mob boss and FBI informant Whitey Bulger, murdered after a prison transfer this past October—Dodge has corresponded with them all. He and Bulger were in contact for some time, and Dodge even has a museum-type display in his home exhibiting Bulger documents and a portrait painting by Tennessee artist Adam Crutchfield. Dodge prizes a Bulger letter complaining about how Johnny Depp made $20 million playing him in Black Mass. The document also reveals that Depp repeatedly asked to visit Bulger, but the mobster said no.

Charles Manson, who died in 2017, only wrote Dodge once, sending a postcard covered in incoherent rambling. Dodge says Richard Ramirez, who died in 2013, had a colorless communication style—somewhat surprising considering this was a guy who, during his first court appearance in 1988, held up a pentagram-inscribed hand and yelled, “Hail, Satan!”

“In our exchanges, he was a very boring man,” Dodge says, adding, “Most of his letters, he would be like, ‘What is your favorite color?’ Or band. Or food. A lot of normalized questions and bland statements.”

Ramirez did get weirder in letters to women, however. “I’ve seen some of this correspondence,” Dodge continues. “Ramirez would ask women for foot photos. If they had children, he would ask about their cup size or what their vagina was shaped like.”

Then, there was the time Ramirez called Dodge and they had their only conversation. “On the phone,” the true-crime collector says, “he sounded robotic.”

WHEN Dodge first began acquiring these relics, he coveted a painting by John Wayne Gacy, who was executed by lethal injection in 1994. Now, Dodge owns two Gacys, one of them depicting “Pogo the Clown.” Pogo—as any true-crime fan knows—was the name of the clown character Gacy played while performing at children’s birthday parties in seventies-era Chicago. Sometimes Gacy did his killing while dressed in this costume.

Dodge also owns art created by Cary Stayner, who murdered four women near Yosemite Park during a few months in 1999. “The Yosemite Killer,” as he was known, remains on death row at San Quentin. Dodge purchased the art from one of Stayner’s former pen pals. He bought the Gacy works from the killer’s former art dealer. Dodge hangs the art of both men on his walls—favorite items in his personal collection.

Not every killer responds to his overtures. The six-foot-nine serial murderer and necrophile Edmund Kemper, who killed ten people between 1964 and 1973, including hitchhiking college women, has ignored Dodge’s letters. Dodge knows of only two people who have received responses from Kemper, a man who once scored a 145 on an IQ test given at an asylum for the criminally insane. Similarly, Anthony Sowell, aka the Cleveland Strangler, won’t correspond, though he did send Dodge two pieces of his art, which got this killer of 11 women in trouble at the Ohio prison where he sits on death row.

Other convicts won’t stop asking for stuff.

“Some prisoners can be divas and have ridiculous demands,” Dodge says. “Dennis Rader is very manipulative. He wants you to number the pages of your letters, format everything correctly, and he’ll correct your paragraph structure, your spelling, etc.” Speaking of Rader, who once served as a compliance officer in his Wichita, Kansas, suburb, fining people for minor infractions like overgrown lawns, Dodge adds, “He’s been by far the biggest pest and annoyance of anyone.”

Dylann Roof, the white supremacist who gunned down nine African-Americans worshipping at a Charleston, South Carolina, church in 2015, did respond to Dodge, who wrote him a letter on the day Roof got arrested. But when Dodge posted Roof’s letter, priced at $1,000, multiple media sources ran with the story, and the killer went silent.

“Roof was the first inmate to blow up on my website,” Dodge says.

The New York Daily News contacted Dodge for a comment. “It’s just an extreme hobby, more than anything,” he told the paper. “Everybody’s fascinated with true crime to an extent, but I take it a step further. Some people get it, some people don’t.”

The Roof letter, bought by a foreign collector, is written in a calm, polite style, and seems normal, except for a moment halfway through when the racist killer expresses a concern: “I also want to ask you the origin of your last name. Is Dodge an English surname? Or is it anglicized (?) name of a different origin?”

DODGE’s true-crime operation began as a hobby: He bought a murder-linked item, and then bought another. Before long, he realized he could parlay his passion into a business, as there seemed to be enough of a subculture to justify an online store, and plenty of murders to keep fueling his enterprise.

These days, Dodge says a pretty diverse crowd visits his site, from strange fans obsessed with certain serial killers to academics, retired cops, and museum curators. He says law enforcement surveils his site periodically, perhaps working on cold cases, studying killers, or looking to see if any “Son of Sam” laws are being broken.

Though convicts themselves can’t profit by monetizing their notoriety, it’s not illegal for friends or relatives of a killer to sell an item. Nor is it illegal for Dodge to receive a letter written by an A-list killer and hawk it for a large sum. Over the years, legislators have proposed shutting down the murderabilia trade altogether, but that hasn’t happened yet.

The value of a true-crime collectible depends on the killer’s profile, high or low, as well as rarity. And when it comes to letters, handwritten documents are worth more than typed ones, naturally, and signatures, as opposed to initials, bump up the price.

“The most expensive murderabilia item to date that I can think of was Bonnie Parker’s personal Colt .38 snub-nosed revolver,” Dodge says. “That sold for $264,000. My most valuable item is Aileen Wuornos’s robe, which I have priced at $8,500.”

Dodge bought the robe from Dawn Botkins, Wuornos’s childhood best friend, and a woman Wuornos wrote to for ten years while on death row—correspondence later compiled into a kind of Wuornos autobiography called Dear Dawn, published in 2012.

“Botkins received all of Wuornos’s property and even her ashes after she was executed in Florida in 2002,” Dodge explains. “The robe came with two certificates of authenticity. Wuornos wore it every day until her execution.”

During Dodge’s years of corresponding with convicts, and running his shop, he has learned to obey some basic safety protocols. He uses a PO box, for example, and advises anyone writing inmates to do so. He puts the matter directly: “You are always at risk of an inmate knowing someone on the outside and finding you, worst-case scenario.”

He says he’s been harassed online—by a killer’s girlfriend, or by supporters of a killer—for selling an item connected to an inmate he no longer communicates with.

“It’s crazy,” Dodge says. “Especially when the killer is just manipulating the girl. I’ve had problems with groupies for Dylann Roof, Erik and Lyle Menendez, and Sarah Jo Pender.”

The Menendez brothers killed their parents in Beverly Hills in 1989. Pender was convicted, along with her boyfriend, of murdering two roommates in Indiana in 2000.

Despite so much contact with psychopaths, Dodge says he’s only had a few uncomfortable experiences. In 2013, a Mexican cartel hitman, José Martínez, sent Dodge a stick-figure drawing meant to represent the collector in a noose. Along with the image, the assassin wrote, “This is one of the ways I killed people.”

The threat stemmed from Martínez suspecting Dodge of being a cop after he asked questions related to Martínez’s former and current trials. Dodge says he was just interested in how the mind of a cold-blooded hitman worked. He was also threatened by Jeremy Jones, aka the Crystal Meth Killer, a man investigators described as a “redneck Ted Bundy” for his Alabama charm and good looks. There was a miscommunication between Jones and Dodge concerning a Bible the serial killer had sent him.

Dodge’s journey into this netherworld of people locked up for acting on homicidal urges has resulted in a change of viewpoint on the death penalty.

“Before stepping into a death-row visiting room, I was pro-death penalty,” he says. “Now I am against it 100 percent. What these killers have done is horrible and they must pay for their actions, but I don’t view these people as monsters. They are just very disturbed individuals, with different underlying factors, issues, and their own demons, which got them into their predicament in the first place.”

Dodge refers to the killers he gets to know as “walking, talking dark history books.” However, his relationship with Dustin Lynch, who at age 15, in 2002, murdered a 17-year-old Ohio girl, might stand apart from the rest. Dodge calls it a kind of friendship.

Lynch—serving 20 years to life—was back in the news in 2013 when he strangled his cellmate, a convicted pedophile. Lynch carved “CHOMO” into the man’s back with a razor, which prison officials believe stood for “child molester.”

To say, then, that Dodge has a tolerance for darkness is putting it mildly.

Consider, also, the fact that his art collection contains works by a Washington State killer nicknamed “The Werewolf Butcher” for his horrific murders in the mid-nineties involving a mother and two children, sexual mutilation, and the displaying of bodies. The man’s name is Jack Spillman, and he’s serving a life sentence in Dodge’s home state.

“The few pieces of Spillman art I have are some of my favorites,” Dodge says in a conversational tone. “It’s very meticulous work. Spillman spends months on just one piece of art at a time, perfecting it until the piece is complete.”

FOR visitors to Dodge’s website, the exposure to so much darkness can be deeply unsettling. At the same time, it shines light on an issue that has always confronted human beings: What do we do with society’s most deviant, violent, destructive individuals? People with psyches so warped they can kill and then go eat a meal. We don’t want to think about these individuals, and we try our best not to. We wish they didn’t exist. But they do.

Dodge’s website makes this realization unignorable. Moreover, it offers a potent window on prison life—a life, a fate, for more than two million of our fellow citizens on any given day.

Some of the items in Dodge’s store might not seem very exciting. A killer’s prison library card. An L.A. serial killer’s purchase order for a new pair of Nikes. An inmate’s visitor application form. But the very banality of these items drives home the grim reality of what it’s like to be on the inside, in the belly of the beast.

There’s an “Inmate Appeal Form” from San Quentin, listing names of numerous death-row inmates, including Scott Peterson, requesting a television upgrade.

There’s a detailed, handwritten letter from a killer describing in precise language how he crafted a “fishing line,” using threads pulled from bedclothes and a flattened toothpaste tube that he then tossed outside his cell. An inmate in a nearby cell, sometimes even on a lower level, does his own “fishing.” If the slender lines with their weighted ends entangle in just the right way, the connected inmates have a way to pass small items.

Stuff like this takes you inside prison life more convincingly than any TV show.

AS for Dodge, he recently launched a podcast on his website. He’s already interviewed Rick Staton, a murderabilia pioneer and Gacy’s former art dealer, and John Borowski, maker of documentaries on historical serial killers, including Chicago’s H. H. Holmes (to be played by Leonardo DiCaprio in a forthcoming Martin Scorcese film based on the book, The Devil in the White City). Other episodes have featured Mafia historian and true-crime author Christian Cipollini, and former Mississippi death-row inmate Michelle Byrom, released from prison in 2016 after spending 16 years locked up.

For future podcasts, Dodge has plans to interview high-profile murderers around the country. People will listen. Our appetite for darkness is not going away any time soon.

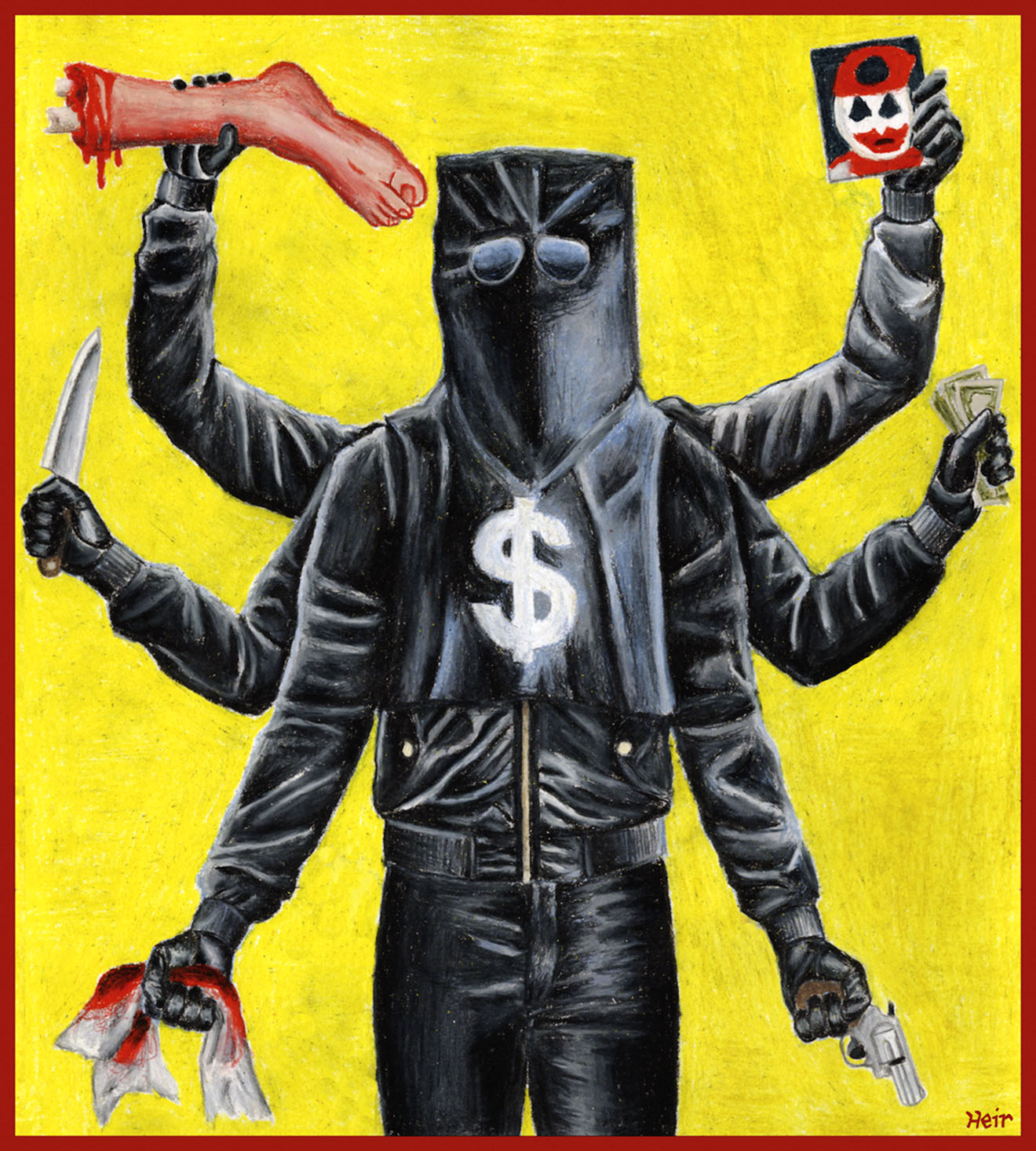

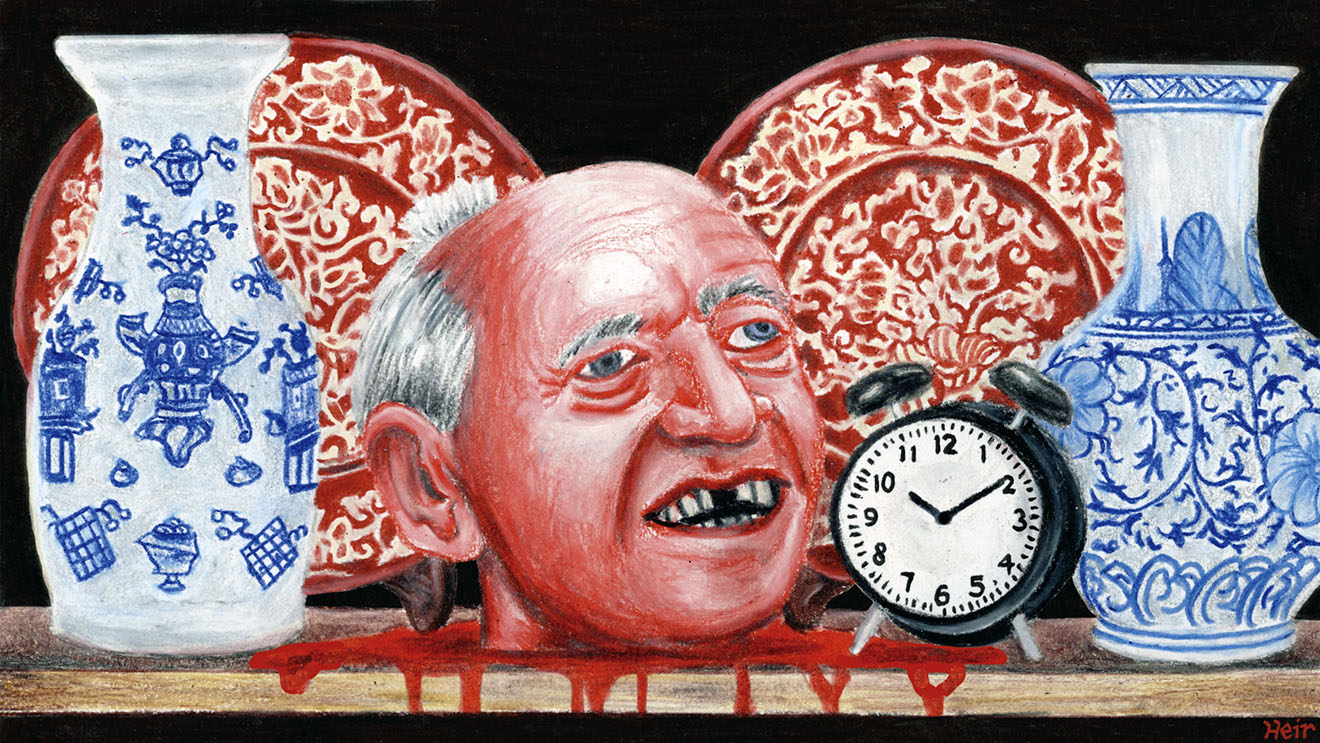

Art by Alex Heir. Photo of Andrew Dodge courtesy of Dodge.