Arsonists Who Helped Women Gain the Right to Vote … Before Valerie Solanas, before pussy hats, there was Kitty Marion. As a member of Britain's Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), the feminist arsonist lit literal fires that helped women gain the right to vote. But historians have washed Marion from memory. Fern Riddell's “Death in Ten Minutes” corrects the record.

“What can we do now,” asked Emmeline Pankhurst, “but carry on this fight ourselves?” She was speaking to a crowded meeting of the WSPU in Hampstead Town Hall, a leader reaffirming her soldiers’ commitment to war. “I want you not to see these as isolated acts of hysterical women, but to see that it is being carried out with a definite intention and purpose. It can only be stopped in one way: that is by giving us the vote!” Powerful words, at a time when the glorious cause had become a “guerrilla war,” fought in the dark with weapons women were not supposed to have. In the years since Kitty had suffered attacks at the hands of the police, endured abuse selling suffrage propaganda, disrupted political meetings, hounded the prime minister, and suffered through horrendous force-feedings while on hunger strike, the WSPU had moved from being a war of words to a war of weapons.

We think of this as a period of window-smashing, women chaining themselves to railings and the rushes on Parliament, but the reality was far more extreme. Guns, bombs, and arson attacks became second nature to the women involved, radicalized by a combination of the revolutionary leadership of the WSPU and the physical violence they experienced at the hands of anti-suffragists, the police, and the prison system. As the government repeatedly betrayed and discounted the suffragettes, the rage felt by the women who only wanted to be seen as equal, and have ownership over their own destinies rather than leave them to the decisions of men, drove the organization to commit highly aggressive acts that have since been erased from our history. The violence of the suffragettes has been sanitized, downplayed, and, in some cases, simply denied — a final injustice to those brave women who made impossible choices in the hope that the ends could somehow justify the means.

From 1912 to 1914, Christabel Pankhurst orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign the likes of which Britain had never seen before and hasn’t experienced since. Hundreds of attacks by either bombs or fire, carried out by women using codenames and aliases, destroyed timber yards, cotton mills, railway stations, MPs’ homes, mansions, racecourses, sporting pavilions, churches, glasshouses, even Edinburgh’s Royal Observatory. Chemical attacks on postmen, postboxes, golfing greens, and even the prime minister — whenever a suffragette could get close enough — left victims with terrible burns and sorely irritated eyes and throats, and destroyed precious correspondence.

Imagine the internet suddenly becoming inaccessible all the way from London to Glasgow, and all phone communication suddenly ceasing. That was the impact of the suffragettes cutting the huge trunk telegram and telephone posts across the country, on numerous occasions taking out communications for the government, police, and ordinary people. Bombs were left outside banks and newspaper offices and could also be sent in the post — one discovered at the South Eastern London District Post Office, made of nitroglycerin and gunpowder, was so large that if it had gone off it would have destroyed the entire building, killing all 200 people inside.

At the site of one of the most daring attacks, on the St Leonards home of the MP Arthur Du Cros in April 1913, the immediate aftermath of the destruction was caught on film. The newsreels were a growing business, and Pathé’s camera arrived while the ruins were still smoldering. As it pans along the shell of the house, figures fill the frame; men trying to salvage roof tiles, women observing the wreckage and a young schoolgirl, standing on the lawn, staring directly into the camera. She turns, looking up at the remnants behind her, while all the other figures hurry across the frame. What did she think of the arson executed in her name, to secure her a future in a utopia of political equality? The dull thud as the workmen’s hammers hit the charred wood was not recorded, but even without sound, the power of the arson attack is clear, a century later. Kitty was the author of this destruction. Did she watch Pathé’s newsreel of the attack’s aftermath, wearing her suffragette colors as the images flickered across the screen?

Du Cros had consistently voted against the enfranchisement of women, which was why he had been chosen as a target, and the razing of his house to the ground was part of the growing “Reign of Terror” that Christabel Pankhurst organized from her Parisian hideaway. She had fled the country after the grand window-smashing campaign and taken up residence in France. Her commitment, and her commitment of the WSPU, to this radical aggressive action, caused a deep schism within the leadership. The Pethick-Lawrences, who had for so long stood beside the Pankhursts and whose newspaper Votes For Women Kitty sold on the streets, were ousted by Christabel and her mother for their opposition to the growing violence at the end of 1912. Determined to exercise full and total control over every aspect of the WSPU, Christabel created a new weekly newspaper for the Union, The Suffragette, priced at a single penny, to carry forward both her edicts and the reports of the actions of other members. Kitty was devoted to the new paper: “The Suffragette became more and more daring and defiant and was continually being raided, everybody, including the printers, being arrested, but never missing an issue since secret reserves were always ready to “carry on.” Many of her fellow suffragettes had now been tasked to carry out destructive and dangerous attacks. As words had not worked, the WSPU issued a new manifesto warning of a “fiercer spirit of revolt” that was now awakened and was “impossible to control.” Emmeline Pankhurst made her directives clear in a now legendary speech:

“Be militant each in your own way… Those of you who can break windows — break them. Those of you who can still further attack the secret idol of property, so as to make the Government realize that property is as greatly endangered by women’s suffrage as it was by the Chartists of old — do so. And my last word is to the Government: I incite this meeting to rebellion.”

Emmeline Pankhurst being arrested while trying to present a petition to the King at Buckingham Palace, 21 May 1914

Emmeline Pankhurst being arrested while trying to present a petition to the King at Buckingham Palace, 21 May 1914

On the platform, Kitty rose to cheer wildly. She was committed to the new violence with a radical and burning passion. The women involved were given many different names in the press, from “wreckers” to “wild women” or the individual “professional petroleuse,” language that conjures up images of these women as the daughters of the French Revolution — a rejected social group bent on political representation, brandishing the colors of the WSPU and shouting out an anglicized war cry reminiscent of “Liberté, Unité, Égalité.” Christabel lost no time in linking the cause to a Francophile revolutionary spirit; she appropriated the image of Joan of Arc, a female martyr who gave her life for what she believed in and was the equal of any man and, under the headings of “Reign of Terror,” “Guerilla Warfare,” and “Fire and Bombs!,” devoted double-page spreads in the Suffragette to reporting the bomb and arson attacks that were now occurring around the country. Following on from photographs and articles of suffragettes still suffering after force-feeding would come the photographs of burned-out buildings and railway stations and parks wrecked by bombs or chemical attacks.

On 29 January 1913, letters addressed to “Mr. George” and “Mr. Asquith” exploded into flames as they were lifted out of postboxes. The envelopes contained fragile glass tubes full of a chemical liquid that, when broken and exposed to the air, immediately caught fire. In the following weeks, further attacks on letters and postboxes came in Coventry, London, Edinburgh, Northampton, and York.

The first bomb attack, and one of the most spectacular in its daring, came on 19 February, when Emily Wilding Davison and her companions succeeded in blowing up David Lloyd George’s new holiday cottage at Walton-on-the-Hill, near Epsom. The Pall Mall Gazette reported the attack under the headline “SUFFRAGETTE TERRORISM,” and that “the perpetrators of the outrage appear to have used a motor-car, and they got away, leaving only two broken hatpins as clues.”

In July 1912, an abortive arson attack on the Nuneham home of Lewis Harcourt, by Helen Craggs and Ethel Smyth, had demonstrated the lengths the suffragettes were now willing to go to. After they had refined their methods, the arson campaign kicked off in earnest on 20 February 1913, when Lilian Lenton and Joyce Locke successfully burned down Kew Gardens’ tea pavilion.

In March, fires raged at railway stations and private homes across Surrey, and railway signal wires, telegram, and telephone trunk masts were cut in Glasgow, Kilmarnock, and Llantarnam. Watching the escalating violence, Sylvia Pankhurst recalled, “Telegraph and telephone wires were severed with long handed clippers; fuse boxes were blown up, communication between London and Glasgow being cut off for some hours.”

April brought with it a full-scale war on the railways: carriages at Davenport Junction, Stockport, exploded after devices were placed underneath the seats. Oxted railway station was decimated by a bomb left in the lavatory. A traveling basket was found, containing a clock timed to go off at 3 A.M., while the fuse had been laid with gunpowder. On 9 April, two bombs were left on the Waterloo to Kingston line, placed on trains going in opposite directions. One bomb was found at Battersea on the train coming from Kingston. In a previously crowded third-class carriage, the railway porter had seen smoke slowly creeping from under a seat. He discovered a white wooden box containing a tin canister, measuring about eight inches by four, in which sixteen live gun cartridges, wired together and joined up with a small double battery, had been attached to a tube of explosive. Packed in among the cartridges were lumps of jagged metal, bullets, and scraps of lead. Four hours later, as a train from Waterloo pulled into Kingston, the third-class carriage exploded and was quickly consumed by fire. Although it was empty, the rest of the carriages were full of passengers, and the risk to their lives was considerable.

Throughout the month, bomb and arson attacks occurred in Abercorn, Portsmouth, Sheffield, Bath, Aberdeen, Tunbridge Wells, Plymouth Hoe, York, Thanet, Birmingham, Newcastle, Cardiff, Preston, London, and Manchester. There was even an attempt to bomb the Bank of England, using a device containing about two ounces of gunpowder, a quantity of hairpins, and a small electric battery, attached by wire to a small chronometer watch, set to explode the bomb at eleven o’clock.

At many of the attacks, copies of the Suffragette were found scattered, or postcards scrawled with message such as “Votes For Women!,” “More To Come/Give Us The Vote,” “Votes for women, and damn the consequences,” “In honour of Mrs Pankhurst,” “Burning for the Vote!,” “Beware of the bomb, run for your lives!” or “Votes For Women R.I.P.” A bomb discovered at the Lyceum Theatre, Taunton, was revealed in the press to have the words “Votes For Women,” “Judges Beware,” “Martyrs of the law,” and “Release our Sisters” painted along its side. At the Smeaton Tower, an old lighthouse on Plymouth Hoe, a bomb — a circular tin canister, containing explosive material and a lit but defused wick — had been painted with the words, “Votes For Women. Death In Ten Minutes.” Every attack was reprinted in detail in the Suffragette; Christabel was determined to use the paper to heighten the passion and commitment of those instructed to carry out these attacks.

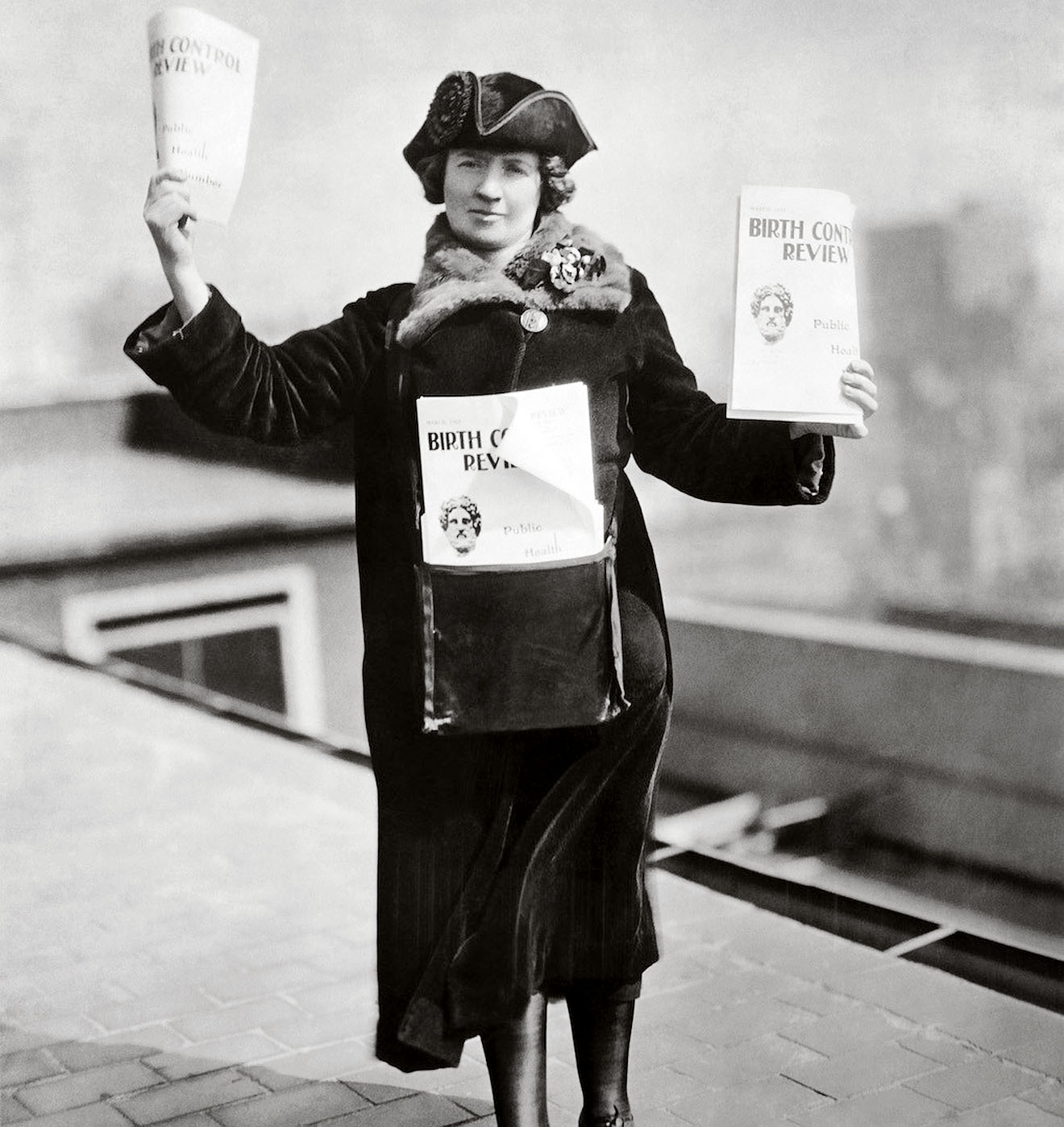

(Original Caption) New York, NY: Kitty Marion ready to sell Birth Control Review in the streets of New York. Photograph, 1915.