“I DON’T want to be a rock star,” says Jennifer Herrema, America’s greatest living rock star.

And what is a rock star these days, really? The term’s been degraded and neutered with overuse, its totemic influence sapped by rock’s downfall from the position of power it held in global pop culture for half a century.

“Rock star” is a compliment issued in a human resources manager’s email. It’s a line in a rap song. It’s a guy buying a $900 John Varvatos biker jacket where the punk club CBGB used to be.

“Honestly, it’s a term of privilege,” Herrema continues, a twinge of exasperated disdain rising in her voice to join the raspy evidence of a million cigarettes. “Like someone saying, ‘You’re a rock star’ to the head coach of a pro football team or something. It’s this thing to bestow upon people who don’t play music. That always seemed so cheesy to me.”

Herrema’s contempt for the term—her refusal to act overly reverential toward rock ’n’ roll in general—is, of course, just more reason to consider her a rock star.

Musicians trying to uphold rock’s crumbling mythological stature have a way of looking desperate and, sadly, it’s become almost the default mode for an entire generation of rock ’n’ rollers living in a world that’s moved on to hip-hop and dance music. (It’s worth noting that Herrema was one of the few rock musicians in the nineties who seemed comfortable around rap music.)

Herrema has spent her career—pretty much her whole life, really—making scuzzy, druggy, capital letter Rock ’n’ Fucking Roll that taps into something close to the genre’s beating, molten heart. It’s music that’s never been affected by trends, never been tailored to a particular audience, and never strayed from her artistic vision, which she shares on a deep level with Neil Michael Hagerty, her longtime creative (and one-time romantic) partner in her best-known—or maybe just most notorious—band, Royal Trux.

At times, when rock ’n’ roll’s drifted furthest from its core, it’s seemed like Jennifer Herrema is one of the few people on Earth keeping it from spinning out entirely.

Times like right now, for instance. The genre’s in sorry shape, with its mainstream aspect defined by monumentally banal arena acts like Imagine Dragons and Muse, and an underground crawling with bands that would rather dig around for obscure nuggets of rock history to revive than come up with a new idea.

To rock fans desperate for a real kick, the new Royal Trux album, White Stuff—the band’s first release in nearly 20 years following a Harrema-Hagerty reunion—registers like a glitter-caked weirdo stumbling into a polite discussion about which boutique overdrive pedal best replicates the guitar sound on a particular obscure New Zealand punk album from the seventies. White Stuff is the reason why we haven’t walked out on rock ’n’ roll altogether.

For her years of service, Herrema has been repaid with three decades of frowning reviews, audiences perplexed to the point of outrage, and a lifetime number of albums sold that the next Drake single will probably blow past in the first couple minutes it’s available.

If you’re like most people, you’ve never heard a Royal Trux song, never seen a Royal Trux T-shirt, or ever heard of Herrema before you started reading this article. But none of that matters in assessing her worthiness as America’s greatest living rock star. Moreover, music popularity—fame and the money that comes with it—never seemed to matter to her anyway.

“Neil and I always felt out of place,” she says, shrugging. “It’s not like it really bummed us out. There was just kinda this wall we were behind and we didn’t even understand how you get over there where all the normal people were. So we didn’t bother to try. We didn’t get the playbook or something. We decided to be happy with the way we called our own shots.”

One of the many ironies of Herrema’s career is that her entire body of work has been built on an utterly unironic embrace of cock-rock sounds and styles like the Rolling Stones’ smacked-out, early-seventies boogie and the cocaine-shiny bubblegum metal of the 1980s Sunset Strip, but has found most of its audience in the world of indie rock. And this is a world—which she fell into mostly by accident—that has a painfully complicated relationship with that kind of big, testosterone-fueled rock music and the dick-swinging hedonism it symbolized.

JENNIFER Herrema’s musical education began when she was a white girl in a majority-black middle school in funk-obsessed southeast Washington, D.C., during funk’s transition from the gooey, warm lysergic vibes of Parliament-Funkadelic into its more hard-edged, synthesized 1980s incarnation.

In high school, she fell in with a stoner crowd that used drugs primarily as a means to more deeply obsess over Led Zeppelin and Grateful Dead records. Somewhere in between, her dad started dropping her off at all-ages D.C. hardcore shows, where she found Neil Michael Hagerty and her musical destiny.

Hagerty was connected enough in the hardcore scene to play guitar in a band with one of the guys from Government Issue, a seminal D.C. punk band, but too genuinely weird to fit in with this subculture’s fairly rigorous social norms. While other D.C. hardcore kids were into political protest and a drug-free, “straight edge” lifestyle, Hagerty was living in a warehouse and dropping huge amounts of acid. One day, Herrema joined him for a three-day acid trip, and they ended up spending the next 15 years bound to each other by love, music, and drugs.

Herrema and Hagerty began making their first music together, laying down the foundation for Royal Trux, in the mid-eighties. At the same time, other former hardcore kids were starting to explore musical directions outside of the genre’s “loud fast” directives while keeping its DIY ethos, in the process creating what came to be known as indie rock.

Hagerty was recruited by one of the early indie scene’s most notorious acts, Pussy Galore, a sneeringly primitivist noise-rock band that flouted hardcore’s political correctness with outrageously objectionable song titles like “You Look Like a Jew.” Hagerty cemented the group’s reputation, and earned a well-deserved place in rock history, when he proposed the concept behind their masterwork, an album-length cover of the Stones’ Exile on Main St. that brilliantly set fire to rock music’s legacy and pissed on its ashes.

After Pussy Galore somewhat predictably self-destructed, Hagerty and Herrema started work on their Royal Trux songwriting in earnest. And as soon as their music got out there, people struggled to categorize it, or even understand what they were doing.

The era’s underground music scene was full of bands deconstructing rock in all kinds of clever ways, but no one went further with the enterprise than Hagerty and Herrema.

They tore seventies boogie rock to shreds until all that was left was a few skeletal riffs, some primordial howling, and a heavily narcotic contact high. It was a singular approach—idiosyncratic to the point of indecipherability for most listeners. The few fans they did have tended to be music critics and owners of small, taste-making record labels.

Their live shows were so shambolic they even managed to affront punk-weened audiences who considered amateurishness a virtue. Around the time of their first album, Gerard Cosloy, the indie-music visionary and Homestead Records exec, described Royal Trux as people who are “barely able to conduct daily order of affairs, whether it’s buying a newspaper or picking up the telephone, trying to be a rock band onstage.”

Still, he found them “really exciting”—more stimulating than Sonic Youth. It was probably the highest praise they received in that era.

Herrema and Hagerty weren’t trolls, but in pursuit of their art they managed to alienate huge swaths of the underground scene. Indie rock fans were offended by their aggressively esoteric noise, their openness about the heroin habits they’d developed, and the air of celebrity and salaciousness that clung to the breathless fanzine and alt-weekly coverage of this scruffily photogenic couple’s thunderous records and narcotics use.

Royal Trux was widely accused of making pretentious, cryptic bullshit, when in fact they were always straight-up about who they were or what they were doing—two people who loved drugs and the Rolling Stones, and wanted to make druggy, Stonesy music.

They may have once been the go-to band for anyone looking to mock indie-music snobs—those connoisseurs of underground sounds who claimed to like, and sometimes actually did like, Royal Trux—but Herrema insists they themselves did not fetishize obscurity.

“Back in the day, indie music was very exclusive and [some of the bands] would try to only have a certain kind of fan,” Herrema remembers. “With Royal Trux, our M.O. was always inclusivity. We didn’t care who you were, where you were from. We didn’t even care if the only band you ever listened to was the Partridge Family.”

After taking reams of criticism for being unlistenable, Herrema and Hagerty managed to piss off a lot of the same people when they started writing songs with recognizable pop structures and hooks on their 1993 breakthrough, Cats and Dogs.

That was followed, in 1994, by Virgin Records signing them to a million-dollar deal, which some observers smirkingly viewed as proof that the major label’s alternative-rock buying spree had reached a new summit of bad decision-making, reckless spending, and unchecked greed. If these two flagrant junkies could get a record contract of that size, the thinking went, then this looking-for-the-next-Nirvana bubble had to be close to bursting.

The deal did turn out to be a disaster for Virgin, but not for the reasons everyone expected.

Instead of simply running off and shooting up their recording budget, Herrema and Hagerty used it to buy a large house in rural Virginia, equip it with a home studio, and get clean, while starting work on three of the most fractured-genius rock albums of the alt-rock era.

By the time they set out to make 1995’s Thank You, the pair turned from deconstructing rock ’n’ roll to its bones to rebuilding it into a Frankenstein monster of clashing essences–canonical “Serious Rock” like Neil Young and Exile-era Stones colliding with the kind of squealing synthesizer prog-rock and high-gloss glam metal that can make critics cringe. The Trilogy, as Herrema-Hagerty called the work Virgin bankrolled, forms a multi-album masterpiece.

Unfortunately for Virgin, the records didn’t make sense to many people outside the band, and the label had no idea how to sell them. To complicate matters, Hagerty and Herrema had no interest in being marketed, and since they had complete creative control written into their contracts, they could veto any of the label’s attempts to make them do boring, profitable things like shoot music videos or tour overseas. The fact that it would be 20 or so years before audiences were truly ready for Royal Trux didn’t help the recording giant at all.

Label execs eventually threw up their hands and let Herrema and Hagerty walk away with the Trilogy’s final album, Accelerator, which they recorded on Virgin’s dime and released through their old Chicago-based indie label, Drag City. Unlike the majority of bands that got caught up in the alt-rock buying spree, Herrema and Hagerty emerged from their major-label period in better financial shape than when they went in, but the stress of years of intense creative and romantic codependency, compounded by their famously ferocious drug habits, eventually overwhelmed them. Herrema’s crisis deepened after the death of her father. Amid rumors of relapses and rivalry, the band dissolved in early 2001.

Looking back at that difficult juncture, and to earlier years with her band and even before then, Herrema says, “Drugs have really had a big impact on my life. All kinds of them.”

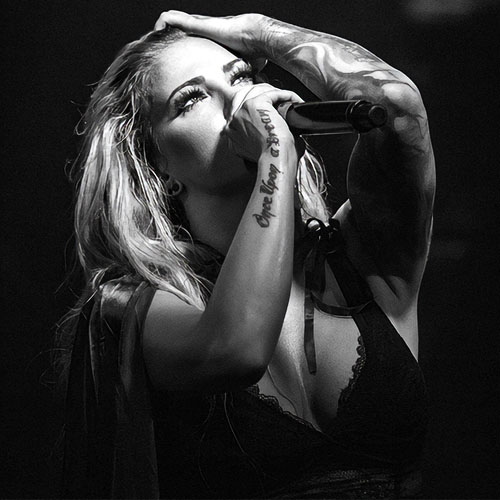

Jennifer Herrema of Royal Trux by David Black

Jennifer Herrema of Royal Trux by David Black

A friends’s older sister turned her on to weed when Herrema was 12. Alcohol and acid followed. When she got into heroin, she got into it deep, developing the kind of rapacious addiction where the user deals with abscessed veins and doctors talk about amputating fingers—the kind of habit that’s just the thinnest of veils for suicide.

“It’s like, which came first?” Herrema reflects. “The chicken or the egg? Were you clinically depressed or did you just do a lot of drugs and then got into a dark space?”

Eventually, antidepressants helped Herrema find stability and stay off smack. Meanwhile, the dissolution of Royal Trux gave her an opportunity to prove that she was more than just her partnership with Hagerty. While he went off to explore the shamanic frequencies of his next project, Howling Hex, Herrema continued refining her trash-rock vision with a new creative partner, Jaimo Welch.

“He was like 17 at the time,” Herrema recalls, “and all he really listened to was Rush and White Lion.”

With their duo RTX (which later evolved into a bigger band, Black Bananas, the only traditionally structured rock combo Herrema’s been in), they used digital production techniques to make her music even more ecstatically trashy and overwhelming.

Somewhere along the way, people started giving Herrema something at least approximating the credit she deserves. Recognition also came from a huge wave of new fans that found her through fashion. As with her becoming a rock star, Herrema never specifically set out to be a style icon, but she’s excelled at it nonetheless.

In the nineties, she perfected a look that—like her music—blended a bunch of seemingly unrelated cultural signifiers: tattered rock ’n’ roller bell-bottoms, truck-stop aviator sunglasses, ratty flannels, oversized Raider jerseys redolent of the era’s gangsta rap aesthetics, and a shaggy mess of blonde hair with long bangs that conjured a 1960s go-go girl gone feral.

Her style seemed thrown together for reasons that had little to do with how its components met the eye. For example, there was that huge parka with a fur-lined hood she seemed perpetually wrapped in, no matter what she was doing or the time of year.

“Basically, I wanted to be inside of myself,” Herrema explains. “So I kind of cocooned myself and put on shades and my hood and had my hair [that way], so I was like basically in my own world.”

Back in the day, her signature underground style earned her a spot in a Calvin Klein ad campaign shot by the legendary fashion photographer Steven Meisel. Herrema was the company’s first model for an iconic, mid-nineties look that came to be called “heroin chic.”

But her biggest fan base didn’t emerge until internet sites like Tumblr took hold, which elevated her postmodern look and appreciation for clothes sourced far from a fashion runway—Herrema once told Vogue magazine her favorite place to shop was Sports Authority—into something like a sartorial philosophy.

She’s had gigs designing jeans for skate-surf brand Volcom, and modeled and designed for Japan’s Hysteric Glamour (Sofia Coppola shot one of the ads). But her biggest mark on fashion comes through appreciation posts collecting her most iconic looks, since these images propagate online, creating new members of a growing Jennifer Herrema fashion cult.

ROYAL Trux is far from the first pioneering indie group to reunite years after the fact, once the rest of the world has caught up to them. But since Herrema is terminally averse to nostalgia and repetition, her reunion with Neil Hagerty feels less like the usual sentimental victory lap and more like returning to a path they’d each wandered away from for a while.

“I played the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland when I was a kid at school,” she remembers, while discussing her dislike of repetition. “I had to do the same lines every weekend for three months. I was like, This is so fucking boring.”

Though rock ’n’ roll might be suffering these days, it’s an art form that thrives on unexpected comebacks. It’s been declared dead dozens of times before and has always sprung back. Herrema knows that the ideas Royal Trux put out into the world—do things your way at all costs, make treasures out of other people’s trash, never back down—have taken root in the hearts and minds of a new generation of artists. And you can’t discount the idea that a new Royal Trux album could catalyze a reaction that’ll launch a thousand scuzzy rock bands and jolt the genre back to life—at least for a minute or two.

But one thing you learn in recovery is to recognize when a problem is somebody else’s to deal with, not yours, and Herrema’s quite reasonably decided that the future of rock ’n’ roll is somebody else’s problem. Besides, the reckless, anarchic spirit that rock used to overflow with—that energy she’s been chasing her entire time on Earth—is alive and well in other parts of the pop world. Take, for example, the wave of young rappers who have used internet savvy to upend the music business, to Herrema’s clear delight.

Her favorite example of this is a rapper she read about who hired a hacker to briefly make him the No. 1 artist on SoundCloud, until the platform noticed and ended the rebel takeover.

“Everything blew up and it got shut right down,” Herrema says admiringly. “But that’s all it took—like an hour—for him to be at the top spot and cause all this hullabaloo.” The underground music and fashion icon smiles. “I like that kind of uneven playing-field thing,” she says. “You can find your own ways through the nooks and crannies.”