The popular determination of the nation’s leading network anchorman has always been a major American ritual, like the naming of a new pope.

Pope Bill I: Bill O’Reilly on Bill

The papacy of TV journalism has been more or less vacant since the retirement of Walter Cronkite in 1982; Dan, Tom, and Peter have been fighting it out the past decade with no real victor.

But now the white smoke can been seen. The new pop is 52-year-old William James O’Reilly. Bill, to the faithful, is the pugnacious, blunt, against-the-grain executive producer and star anchorman of Fox New’s The O’Reilly Factor — an hour-long cable news talk show on which the host gets to express his opinion about public and private affairs, what’s bugging the American people (or him) on any given night — the good, the bad, and the completely ridiculous in American life.

O’Reilly’s show, the crown jewel in Fox’s nightly three hours of news talk — an art form that sometimes seems like verbal mud wrestling, with pundits and unpundits seeing who can outdebate the other by yelling loudest — stands out from the rest of its kind. Usually this new breed of news show gathers people from both sides of an issue, winds them up, and lets them go at it. The person in between is an “immoderator,” as Ben Wattenberg of PBS’s Think Tank calls them, “giving the illusion of balanced discourse.” The O’Reilly Factor is the one hour that seems to rise above a food fight in the evolutionary process known as television news.

That a mere cable news anchor guy could reach such an exalted position as the nations most prominent anchorman, if not the most universally respected (yet), is the result of a major revolution that is taking place in news. The traditional network evening news show has been dying in the ratings. The combined viewership for the nightly broadcasts anchored by Jennings, Brokaw, and Rather last year, according to the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, was down to 50 percent, compared with 59 percent in 1998 and 71 percent in 1987. It’s declining even more in prestige. People don’t watch the 6:30 network evening news the way they used to. They are often not even home from work yet, or they have heard all the hard news on the radio, local TV, the Internet, or on their Palm Pilots. They know all about it.

And basically they don’t learn anything different from the old established networks. It’s always the same snail-darter story. If you see the snail-darter story on Dan, you know you’re going to see the snail darter on Tom. It’s the same stand-up, same poll, same terrible storm. All of which you heard already. Nor do Dan, Tom, or Peter tell you what to make of it. What does it all mean? Why is everything so crazy in this mixed-up world? They always seem afraid to say.

Bill O’Reilly isn’t. Instead of rhetorical questions, O’Reilly has the rhetorical answers. At least he thinks he does.

O’Reilly works for Fox News Channel, whose parent, Rupert Murdoch’s Fox TV, gave us such contributions to Western civilization as Cops, Greed, and When Animals Attack. It is the cable news network that hails itself as “Fair and balanced. We report. You decide.” And O’Reilly, his detractors have decided, is the least fair or balanced — a man who even replaced Rush Limbaugh as Public Enemy No. 1 for those of the liberal persuasion, and a first-class pain in the ass to everybody he finds fault with, especially the purveyors of what he calls political and social “hokum.”

Pope Bill was elected by a kind of college of cardinals: American cable-viewers who sit on their couches in their TV pews and vote with their fingers every night. They are the blue-collar crowd, “the folks,” as Bill calls them, the regular guys, average Americans, the people for whom he believes he speaks when he cuts through all the rhetorical bullshit while interviewing the newsmakers. The folks are not necessarily what used to be known as “working class,” since very few Americans still want to be called that in a day and age when janitors are called “sanitation engineers.” What unites his viewers, regardless of class, is they are the people who are mad as hell about the way things are going, but don’t know what to do about it — except to watch their Bill every weekday night at 8.

The Factor, as the show is called by the true believers, starts off with these magical words: “Caution: You are about to enter a no-spin zone” — an Orwellian (black is white, peace is war) concept, since watching the show is like being in a Laundromat with all the machines on spin cycle. The difference is it’s all O’Reilly’s spin, rather than what’s usually seen on TV news.

Right now O’Reilly is the closest thing we have on television to the late Howard Cosell, who, in the pre-Dennis Miller era of Monday Night Football, also used to tell it like it is, before fame went to his toupee. I still remember seeing steel-workers in the taverns of south-side Pittsburgh throwing empty beer cans at the screen whenever Howard came on — a sign of love and affection in blue-collar western Pennsylvania. O’Reilly brings out that same kind of emotion. He is the most loved and loathed man on television today. The TV critic in me thinks he is the best thing to hit TV news since the invention of hair spray. He has devised a new approach to delivering news and commentary, something that really hadn’t changed that much since TV took its format from early radio news.

Since last December, Bill’s folks have been voting for him in increasingly large numbers in the popularity contest that is cable network news. Now starting its fifth year, The Factor in July finally broke the million-viewer barrier, hitting an average 1,000,010, up from 427,000 last July, a 137 percent jump. He is kicking the shit out of rival talk-shout shows like Hardball and Geraldo on CNBC, and, most importantly, he even beat out the graying hair apparent to the throne, Larry King, one recent week by a Nielsen count of 17,000 viewers — a significant number, because Fox News is available in only 64 million households compared to CNN’s 81 million.

There is the smell-of-fear factor about The Factor at CNN. As I write, ye olde (established 1980) news network is in talks with none other than Rush Limbaugh to counteract the O’Reilly wave, the thought being that — even a simulcast of Rush’s radio show would create a schism on the right and draw away some viewers of the conservative persuasion.

The Super Factorman has just signed a six-year contract with Fox News that sources say will earn him $24 million to $30 million.

His first book, his bible — The O’Reilly Factor: The Good, the Bad, and the Completely Ridiculous in American Life — has already sold 1. 1 million copies and was on the New York Times best-seller list for 32 weeks (11 of them at No. 1), all after a miniscule first printing of 30,000.

His second book, published last October — The No-Spin Zone: Confrontations With the Powerful and Famous in America — is a compendium of his favorite interviews, including those with noted philosopher Sean “P. Diddy” Combs, James Carville, Dr. Laura Schlessinger, Al Sharpton, and Dan Rather. It also has fantasy interviews with the ones who got away (Hillary Clinton). All of which are treated as the most important debates since Lincoln-Douglas.

Which they will be by the time Bill gets through flogging this second book. He is one of the great televisual marketers of all time, absolutely shameless in self-promotion. The Factor T-shirts had to go back into production after the first night Bill mentioned them on the show. As that time-worn adage goes, “The pen is mightier than the sword. Mightier still is TV” The Factor sometimes sounds like a public-TV pledge drive with so many premiums available for supporters pledging their allegiance to The Man.

A new half-hour 11:30 P.M. syndicated show hosted by Bill is scheduled for summer 2002. Titled Last Call, it will feature Bill looking back at the day’s events, a more hip version of The Factor, aimed at the territory of Dave and Jay, the late-night commentators he admired most during the last election campaign. A radio show is being discussed. O’Reilly also writes a weekly newspaper column that appears in more than 100 outlets. His first work of fiction, Those Who Trespass — a murder thriller in which the author manages to assassinate some of the real-life characters who have plagued him over the years-sold 80,000 copies. Mel Gibson is talking about optioning it for the movies. “Gibson is a big Factor fan,” O’Reilly says.

He is on his way to becoming the pope of all media.

Not everybody is as enthusiastic about O’Reilly as I am. “Prick,” “blowhard,” “gasbag,” and “media fuhrer” are some of the kinder things he has been called in that effete magazine GQ. “A loudmouthed cable-news talker with an ego bigger than his audience,” Brill’s Content called him. “Opinionated pundit pummeler,” People magazine said. “Worthless,” according to Tom Shales of the Washington Post.

His enemies are everywhere. Tucker Carlson, the bow-tied rival spinner at CNN’s The Spin Room, said, “Only masochists would go on [O’Reilly’s] show — or watch it.” Between the masochists and the sadists who love to see Bill make people squirm in his sometimes brutal interviews with the big and small players from academia and politics, there’s a real random cross-section of America’s cable-viewing universe.

This love-hate relationship can even be found in the same household. An above-average American family rent asunder by the O’Reilly phenomenon is the Navaskys of westside Manhattan. Annie Navasky is a Wall Street stockbroker. As soon as her husband turns on The Factor she goes to the kitchen, where she prefers to stare at the refrigerator door.

“I cannot stand to hear his voice,” she explains. “It’s horrible. Truth of the matter is, I don’t know whether it’s O’Reilly that I hate or the part of Victor that has to listen to him every night.”

Her husband is Victor Navasky, publisher of The Nation magazine, what Fox newsies might call a left-wing rag. “I find him interesting,” the least likely O’Reilly groupie declares. “It’s the way he presents himself. He’s not like Rush Limbaugh, who says, ‘I’m this big fat right-wing jerk, but I know more than you about everything.’ O’Reilly, a tall, slim guy, presents himself as someone who has his own ideas about things, but he’s above the traditional right-left fray.”

The horrific tragedies of the terrorist attacks in September changed the nature of the cable news wars. Basically, it was the story that would be “carrying us through the rest of the year,” O’Reilly said.

“O’Reilly is against capital punishment. ‘It’s not cruel and unusual enough,’ says Roger Ailes, the head of Fox News.”

“The ones who brought the most incisive take on the coverage will win the TV ratings wars. There are two ways to go: the company-line way, which most of the networks do. Wait for the government to tell them what the situation is. So they react to whatever the government says. Or, two, you can start developing a point of view on the story, get people who are experts in various fields. ‘Yeah, this is what the government says, but this is what really is going on.’ And that,” says O’Reilly, “is what we’re going to do.”

But Navasky, for one, has not liked what he’s seen of O’Reilly’s approach to covering the aftermath of the terror attacks. “Anyone who dissents, or doesn’t agree with him, is made to sound somehow unpatriotic.” O’Reilly scoffs at those who see him weak on the First Amendment. “We have probably used more people who have dissented than anybody else on TV. My thesis is, if you can back up your dissent with a well-thought-out argument, there’s no problem. But if you’re just venting because you don’t like the United States of America in general, which is the agenda of 90 percent of the [dissenters] we’ve had on, then I’ll let you have it.”

Examining Fox News as a den of media iniquity is a major preoccupation in the country today. Deconstructing O’Reilly, the symbol of all that is wrong with Fox News, is a cottage industry. Scholars study his shows frame by frame like the Dead Sea scrolls, looking for conservative bias. Respected intellectuals like Michael Kinsley of Slate.com, James Wolcott of Vanity Fair, and staff members of FAIR (Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting) do exegeses on the O’Reilly Factor book and his commentaries and on-air confrontations with the mighty, trying to find indictable inconsistencies.

The first thing the O’Reilly bashers try to nail him on is where he grew up. O’Reilly usually says Levittown, a lowermiddle-class community in Nassau County, Long Island.

“Why would he want to lie about that?” I asked Peter Hart, the O’Reilly scholar-in-residence at FAIR.

“It’s part of his persona,” Hart says. “He plays a character for Fox, and the character is working-class tough guy, champion of the little man. It makes more sense for him to flaunt his workingclass credentials, a blue-collar Catholic who claims to be on the side of the underdog.”

Michael Kinsley, who once represented the left on CNN’s shout show Crossfire, found that Bill actually grew up in Westbury, bordering Levittown. What Kinsley and others in this subdivision of O’Reilly Studies seem to ignore is there have been many Levittowns. After World War II, Levitt built so many houses, the local post office couldn’t handle them all. Some were put in the postal districts of East Meadow, Hicksville, or Westbury, the site of the O’Reilly manse where Bill grew up and his mother still lives.

“The reason I wrote that I was from Levittown,” O’Reilly explains over lunch, “is because nobody knows what a ‘Westbury’ is, but everybody knows a ‘Levittown.’ It’s kind of shorthand. I’m still a Levittown guy. I still go to the Levittown pool. And to seize on that, trying to make me out a charlatan, is dishonest. They’re just trying to erode my credibility. I say just take a ride out there. All the neighbors get a big kick out of the dispute.”

To Peter Hart, “the whole lower-class shtick is a little trick he does that makes it perfectly clear that he’s one of the folks.” But is that such a crime? Would it be better for O’Reilly to identify himself as on the side of bankers and industrialists who also live on Long Island?

“It complicates his life story,” Hart says. “So many of O’Reilly’s tales are all about the importance of class in America and the way he had been snubbed by people who looked down on Irish-Americans of working-class origin.”

How can he be a working-class guy when he went to Harvard? his critics ask. “Yes, that’s right,” O’Reilly confesses. “At 42. I barely got into Marist College at 18. I had to paint houses. Levitt houses.” In 1996 O’Reilly left a lucrative job at the tabloid TV magazine Inside Edition to work toward a master’s degree at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

Something else that spooks a lot of people about O’Reilly is that they’re not always able to pigeonhole him ideologically. For example, O’Reilly is against capital punishment — but for odd reasons. “It’s not cruel and unusual enough,” says Roger Ailes, the head of Fox News. “He would like to torture them. It’s a different take, anyway.” O’Reilly’s also for gun control. He’s an environmentalist. He may lean to the right, but he is not a doctrinaire knee-jerk conservative with his feet planted firmly in midair. “He is what we might call an independent,” says Navasky. “Or even a libertarian.”

All agree that he can be rude and obnoxious when interviewing guests on The Factor. “I see myself as Roger Clemens,” O’Reilly says. “Because I’ll brush you back during the debates. I’ll put it right on your chin, especially if you’re annoying me. I’ll get you right off that plate and I’ll buzz your right ear.” (The baseball metaphor is not a stretch; O’Reilly was a pitcher growing up, and a fairly good one.)

But his interview style isn’t what the media establishment finds so threatening about this man — who only has a million viewers compared with the 20 million who still watch Tom, Dan, and Peter. What is so scary about him? Maybe they are afraid of him because he is something completely different on the TV landscape. They have never seen anything like him before. The Factor is a news show that is more like the Op-Ed page of a newspaper than a talk show. They can’t quite get their eyeballs and fingers around it.

Traditional news allows for no commentary. It’s all “straight reporting.” As Uncle Walter used to say every night of his ten years of giving the Pentagon position on the Vietnam War back in the seventies: “And that’s the way it is.” But it wasn’t. On the evening news at CBS, the “Tiffany network,” they used to have at most 90 seconds of “commentary” by Eric Sevaried, who was famous for having the broadest shoulders in the media since Clark Kent. “Eric Severalsides,” we used to call him, because he would try to be fair … balanced … you decide. You couldn’t find out from the establishment news what was really going on. Edward R. Murrow tried to tell us for a while. He was fired, in effect, pushed out by CBS management because he was a pain in the corporate ass, always trying to be honest about social and political issues.

O’Reilly is such a threat because not only is he a populist (relatively), but he’s a trained newsman who has a forum which he uses to give his version of why it’s such a crazy world. He doesn’t try to hide his opinion. He is as subtle as a Long Island Rail Road express train. From his opening “Talking Points” and commentary, he tells you what’s good, bad, and completely ridiculous. Some of which make a lot of sense.

It’s no earth-shaking revolution he’s preaching. His message conveys the same traditional values he was taught growing up in suburban Long Island. Parents should set up and control their environment, big government can be bad, and gay activists should keep it to themselves. (“Dykes on a bike, take a hike.”) He is against ten-m.p.g. SUVs as a waste of gas. He is the only one on TV who calls government solutions for drug interdiction insane. You and I may argue with some of the planks in his program for a sane society. Nobody is perfect. In the land of the blind, so it’s said, the one-eyed man is king.

Who is this one-eyed guy anyway?

Uncle Bill is the antithesis of the man he considers his chief rival as the nation’s opinion leader. “Larry King works,” Roger Ailes says. “So does Bill. They’re both originals. Copies don’t work on TV Whether you like Larry or not, you can go out on the street and find 50 guys who are better looking, who won’t do any homework, and you can put them in suspenders and put them on the air, and they’ll fail. Larry doesn’t fail, because there’s a nice-guy quality to him. Even though he himself announced that he’s a liberal, he’s not agenda-driven and he doesn’t embarrass people he doesn’t agree with. So people who do his show know that he’s never going to ask them a difficult question. [If] he had O.J. on, he wouldn’t bring up the recent unpleasantness about his wife. [But Larry might ask O.J.] who his tailor is: ‘You’ve got great clothes, you know? Talk about your golf swing, your 2000 yards at Buffalo.’ {Larry] wouldn’t bring up the cocaine. He wouldn’t bring up any of that stuff.

“O’Reilly would start off by saying, ‘So you murdered your wife and you take cocaine. Now tell us why we should even talk to you.’ “

“Larry is more like an emcee,” Bill says of his arch rival. Larry didn’t want to tell me what he thought of Bill.

O’Reilly today is the most feared interviewer working the sit-down circuit since Mike Wallace pitched his fastball on 60 Minutes. Like Wallace, he can make famous people sweat with a mere call from The Factor booker. That’s why he doesn’t get the top guests that Larry does. Politicians intuitively know they will have to commit the mortal sin — for a politician — of dealing in the truth with Bill. O’Reilly is the sort of weirdo who tells people to stop lying.

There is some debate about who created this monster. Roger Ailes, the leading candidate for Dr. Frankenstein, had his own talk show on the America’s Talking network — the NBC cable operation that became MSNBC and is the model for all the cable network news rivals to CNN. “I interviewed O’Reilly [on America’s Talking] and I heard he was a bit of a hothead, hard to handle, difficult guy, problematic in his job at ABC,”

Ailes says. “But in interviewing him I thought there was something more there, that he was smarter, had a take on the issues, was fearless in terms of his ability to express them.

“So it was sitting across the table on my show and watching him, and listening to him frame arguments that stuck in my mind. I said, ‘I think I can create a television show with this guy.’ And by the way, everybody told me not to. Because Bill had been in the business 25 years and never been a star.

“He’s not totally insulated like Howard Stem. Stern, says O’Reilly, ‘wanted to be a rock star. I don’t mind people saying hello.’”

“He failed when he first started. I had him at six o’clock, and the show wasn’t working. Right now I give him full credit for the show, but the truth is I managed that show very carefully when it launched, and helped develop it. He came in and felt really bad: ‘You know, I’m just not getting any traction. I don’t know what’s going on.’ And I said, ‘Bill, I actually think you’re pretty good and I think your show is pretty good. I think we’ve gotta do a few things. You can’t be an angry white man for a full hour. You gotta lighten up a little bit in places. But I think the mistake is really mine. I think I have you at the wrong time period. So I’m going to give you the best time period on the network.’

“And I was right. It needed that time, it needed more sets in use, it needed a better lead-in, and I was able create that. So it began to catch fire almost immediately.”

People talk about The Factor as if it’s a talk show. But in the opinion of Ailes, O’Reilly is a newsman first: “He’s smart. Smarter than people think. Most television people are idiots.”

O’Reilly was born September 10, 1949. “I hit it all perfectly,” he says. “I hit Elvis. I hit the Beatles. I hit the Vietnam War.” Of course life wasn’t about politics when Bill was a kid; he was more interested in baseball, football, ice hockey.

“I was one of the few kids who didn’t want his father coming to the games. We would get into fights. I was so competitive. And he would kind of like say, ‘How come you’re not having more fun? Just enjoy it. Relax.’ But I wanted to win. If I didn’t win, I was teed off. That served me well in television. Because I mean, you gotta win.”

He went on to play semipro baseball in Brooklyn with a team called the New York Monarchs. “I was the only white guy on the team. We played double-headers on Sundays at Oceanside or one of the southside parks. I would tell the manager, look, I’m not pitching the first game. Because these guys were all hungover from Saturday night. By the second game, they might be awake. They were the best ballplayers I’ve ever seen. Unfortunately, half of them were heroin addicts, but they were still great ballplayers. I mean, by the fourth inning the captain would be running off: ‘I got a headache.’ It was my first race-relation deal. I was known as White Boy. That was my name. It wasn’t Bill O’Reilly. ‘White Boy, you better get that ball over the plate. I gotta get out of here.’ I mean, I was more afraid of my team than the opposing team. And that’s why I did so well. I was 20 at the time. ‘My kids are that old,’ they’d say. But they kind of liked me, sort of a curiosity. They’d say, ‘Don’t be looking at my woman.’ I never had so many laughs in my life. I know how Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy and those guys did it.

“I was never brought up with any black guys. I went to all-white schools. My neighborhood was Jewish, Irish, Italian. There were a few black guys on my college football teams, but not really ghetto guys.”

At Marist he was a quarterback. “I could throw and I was a kicker. I made varsity as freshman and played three years.” Then he did something weird.

His junior year he went to the University of London. “My father just looked and said, ‘What are you doing that for? You’re the star quarterback.’ By that point I knew I wasn’t going to make the pros or anything. And I said, ‘You know, this would be more interesting.’ He didn’t get that at all. It was the best thing I ever did. But where I came from, people didn’t spend a year abroad. It really helped change my whole perspective.”

It was in London that the English taught him all about class, a major theme of his show, his books, his life.

“I was always in my own class in Levittown. There was no other class. I mean, I knew that there were ghettos, but we never really saw them. When I used to go to the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium, I would drive through, but I wasn’t hanging there. And all my friends and all my family were from the same lower-middle-class working environment. At the University of London I really saw the difference between the aristocracy, which attended college, and everybody who didn’t have a shot.

“When I came back to America I started noticing the difference. It’s not as pronounced. The difference in America is that we don’t admit it. As soon as you open your mouth over there, they know everything. It really hit home when I got to the networks at ABC News. Because guys like Forrest Sawyer and Stone Phillips were getting a lot more attention than I was. And I said to my parents, ‘Why didn’t you name me Redwood? Couldn’t I be Reef? If I was Reef O’Reilly, man, I would be anchoring the weekend news.’

“So that’s why I was so happy this cable outfit sprung up. Because there is no class war. Over here it’s who performs.”

O’Reilly has always done weird things on his way to the top, marching to his own amplified jazz glockenspiel. He was a high school teacher (history and English) in a rough neighborhood in the Miami area before dropping out to take his first master’s degree in journalism at Boston University. He broke into TV in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he was a big hit as reporter and wiseass. He became a pain in the ass at a bigger TV station in Dallas, where he did the same things, and they hated him. And it wasn’t a good career move when he had the gall to question why the news director had hired a new anchorwoman just because the guy was sleeping with her.

He made his share of enemies with his brashness in local news at New York’s CBS affiliate. “I was just a punk reporter at Channel 2,” he recalls, “and I’m standing in line, and here comes Morely Safer and he cuts in line. I go, ‘Hey, Mr. Safer, there’s a line here.’ Everyone is like stunned, and he went to the back of the line. But that’s why I’m Mr. Popularity.”

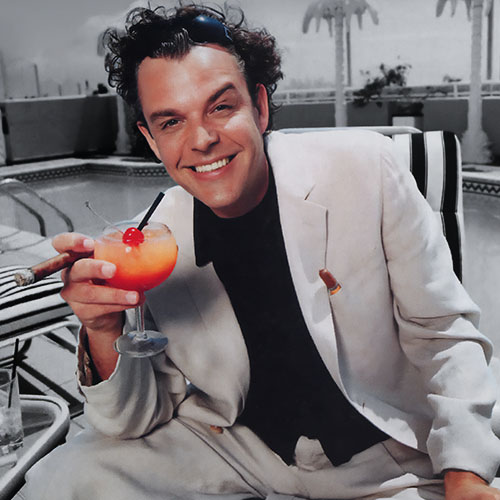

It was a thrill to finally meet Mr. Popularity one afternoon and watch him eat a Caesar salad and a piece of lamb. It was like having an audience with, well, the pope.

O’Reilly is a surprising six-foot-four — like Howard Cosell, whom you expected to be like a rat crawling along the gutter but who in fact was a giant, stooped over from talking to people, most of whom were beneath contempt. TV pictures lie. They make everybody seem the same size. O’Reilly doesn’t play the height card. He is a beanpole kind of guy, with thinning, sandy-colored hair, who lopes down the street wearing the camera-ready Filene’s Basement gray suit and light-blue shirt, walking in the door of Fox News without an entourage, hardly noticed.

His day begins in Manhasset, where he lives in a modest Colonial house with his wife, Maureen, whom he married five years ago, and their two-year-old daughter. “She is as old as Jesse Jackson’s,” O’Reilly says, “but she’s legitimate.” After a conference call with his staff about the day’s program, he plays with his daughter awhile. Then he goes out for breakfast at the Village Coffee Shop in Manhasset.

He’s not like Howard Stern, who totally insulates himself from the community. “See, what Stern did,” O’Reilly says, “he wanted to be a rock star. I didn’t want to be a rock star. I put a cap on now and I don’t mind people coming up and saying hello to me. Nobody bothers me. I zip around. I take a book and go to the beach. I don’t need to have bells and whistles going 24 hours a day.”

What he likes about his morning headquarters in the coffee shop is that it has cops, firemen, the construction guys. “They just filter in and I just say, ‘Hey, what’s going on, what do you think,’ and they like this, they don’t like that. It’s a good barometer of what they’re talking about, I think. Long Island has changed, but I still like it. There’s an edge to it that is found nowhere else in the country.”

Then he drives into the city. “Nothing fancy. It’s a GM car. I don’t like to get too specific.” He gets stuck on the Long Island Expressway like a regular guy. “The Expressway,” he explains, “has been under construction since the Revolutionary War. I think they want to wrap it up some day before my death. That’s all I want before I die: no cones on the L.I.E. They build roads better in Zambia than they do out here. And they use coconuts.”

Sometimes he takes the railroad. “Everybody knows me. It’s like, ‘Hey, how you doing, Bill?’ It’s good because I get to talk to people. The conductors all telling me what they like and don’t like.”

He never takes a limo, the vehicle of choice for stars of his magnitude. “If there’s a meeting or something like that, Makeda [his assistant] always tells them, ‘Don’t send a limo.’ All I need is Mike Kinsley seeing me riding around in a limo. I don’t even feel comfortable in a limo. I never know what to do with my legs. I keep slipping off the seat.”

It’s 2: 15 P.M. and the Factor staff of nine producers, bookers, and interns has come to present everyone’s ideas for the week’s shows. The pitch, as it’s called, is crucial. The show is divided into five blocks labeled A to E, into which possible subjects — talking points, crime of the week, most ridiculous — are sorted. The five blocks can be made out of lead or gold, in terms of ratings.

O’Reilly so far has the golden gut, that inner something, like a radar beam that guides him in the selection process. It’s not politics so much as what he calls “emotional content.” Emotion, emotion, emotion! A topic that will keep his viewers’ attention while allowing him to get something off his chest or stomach before they turn that dial.

The cable news audience has the fastest fingers in the West — and every-place else — O’Reilly explained at lunch. “There should be an Olympic event for remote-control users. Americans would win easily.”

His staff people have been going over the news like a vacuum cleaner. They are looking for stories from local markets that do not usually get a national spotlight, that raise compelling or challenging (to O’Reilly) issues. The team troops in, armed with clips from the wires, the Internet, newspapers, and magazines. They always have a piece of paper to back up a pitch. Facts. Or even so-called facts. O’Reilly is the sole decision-maker, a role he is happy to play. He has total control here, which he didn’t have in his other life as a TV newsman. He separates the wheat from the chaff. On other shows, O’Reilly remembers, they sometimes would keep the chaff and throw out the wheat.

“O’Reilly doesn’t like SUVs: ‘I don’t think they’re any good for society.… That will generate thousands of letters.’”

He takes his seat next to bulletin boards filled with yellow, blue, and pink cards, indicating works in progress. The pitch meeting starts with an inspirational message from Bill:

“Okay, a couple of notes. Larry [King] has now decided to go tabloid, which is, you know, going to spike him up a little. They did Loretta Young’s love child last week and Rock Hudson’s gardener or whatever. Well, we can’t really count on it. But if you do find Lon Chaney’s love child, let me know …. The political stuff isn’t working for anybody …. Okay, what you got?” (The meeting is run counter-clockwise, left to right, for those looking for bias.)

“In Tennessee,” a production assistant says, “eight people brought a complaint, a lawsuit, against the foster care there, and won, and the judge agreed that the state had mismanaged the welfare system. The state agreed to settle the lawsuit and spend millions—”

“I want you to know that while you were saying that,” O’Reilly interrupts, “I was thinking about the Mets game.”

“Wait, wait, they put a nine-year-old in a homeless shelter for one year as part of his foster care.”

“Next.”

“A First Amendment attorney has come out against obscenity laws,” an associate producer begins. “He says obscenity laws actually hurt little children.”

“Why?”

“Because it doesn’t give them the critical thinking skills to live in our society.”

“Okay, I’ll take it. Next.”

The working principle of brainstorming think tanks is not to make people feel bad. O’Reilly tries to keep it light.

“There is a woman in the middle of Utah who says her neighbor has a topless maid. She was wearing a thong bikini to do her gardening. We have video.”

“All right, we’ll do it. It’s ridiculous enough. My Inside Edition past is flashing before me.”

“Erin Brockovich,” a booker says. “She is now going to be with the people in upstate New York, the homeowners whose homes have been contaminated by —”

“I only want Erin Brockovich if she had an affair with [Gary] Condit.”

And so it goes. Forty-five minutes of batting practice, sorting through the good, the bad, and the completely ridiculous.

The team heads out of the locker room for the game as O’Reilly gathers up all the paperwork and files for the day’s five segment blocks and lopes up to his office to do the writing for the show, which tapes at 6 P.M.

“This is the mail for today,” he says proudly, pushing aside several U. S. Post Office containers on the couch to make room for me to sit down. “We get 30,000 letters a week. Nobody believes me. This is just surface mail, not the e-mail. This is just people putting a stamp on a goddamn envelope. There’s 2,000 pieces here today, and we got about 3,000 e-mails.”

Is that a good day?

“About average.”

What kind of subject really tees them off?

“If I say Bush did something stupid. If I come down on somebody who they like, I’ll get a torrent of mail, not abusive so much as they just are disappointed in me. What happened to me? Or: You’re a conceited guy, why don’t you go back to Russia? Something that gets them real upset is the story about the SUVs. I’m, like, against SUVs. I don’t think they’re any good for society at all. It’s a self-indulgent thing. Well, anybody who has an SUV calls me an SOB. You get a lot of initials flying around. That will generate thousands of letters.”

A production assistant hands him a Nielsen ratings sheet. He studies it as he talks. He tracks numbers the way the National Hurricane Center follows weather patterns. What he’s tracking today is Hurricane Larry. King’s numbers are going up, just as O’Reilly had predicted of the new tabloid slant. “He is not as dead as he had been for a while. I was at Inside Edition. I know what tabloid can do. You have to stop them.” Basically, “them” is everybody. “Not only are we up against the other cable networks. King. Geraldo. Williams. We also have to look at Survivor, Weakest Link, whatever else they got on at 8. I gotta throw in something to make sure. The cable audience cruises, and you gotta get them involved fast as they go around the dial. They have no idea what they’re watching; it’s hypnosis now. But they do know if they’re bored.

“My world basically is figuring out what night it is, and how to engage the audience at the top so they’ll stay for the first four or five minutes, and then tease something they want to see. It’s a psychological-warfare game.”

He is sitting at his desk with his feet planted firmly on a HILLARY doormat, surrounded by his bevy of diplomas: Marist 1971 through Harvard 1996. He also has his white-and-red Marist varsity jersey framed, and the front page of a newspaper from the day after President McKinley was shot (September 6, 1901). Few TV news stars think about McKinley anymore.

Three o’clock. It’s time to write the show. This is stranger than McKinley. Hardly any superstar journalists write their own material. Which accounts for the puzzled look sometimes seen in their eyes, as if to say, “Am I really saying this crap?” Maybe they will change a few words like “and” or “but.” Then they’re called “managing editors.” O’Reilly does it all, from the commentary at the head of the show to the responses to reader mail at the end. He even does the promos.

It takes him less than two hours to bang out the copy — as he says, like an old newspaperman. It sounds like O’Reilly talking. And it is. He was always a fast writer. The reason Peter Jennings loved him so much when he was at ABC News is that Jennings could always count on O’Reilly to write him a two-minute tease for the upcoming network evening news with three minutes to air.

And then it’s show time. O’Reilly dresses for the show, picking one of the nondescript blueish ties that looks like a leftover Father’s Day gift. I go down with him to the ultimate No-Spin Zone for the taping.

It’s fascinating standing on the sidelines watching the other guests waiting to go on in the various blocks. They look like Christians on their way to face the lions in O’Reilly’s Colosseum. “You make them nervous,” a production assistant says as he leads a sweating victim away. O’Reilly denies it.

O’Reilly has a unique style of debating. “He tends to be intolerant of people who don’t agree with him,” Navasky says. “It’s not that he argues them down. He assumes them down, as if only a cretin could think the way you do. For such a thing, he won’t even dignify it with a comment. He also cuts them off.”

“Don’t be rude,” the control room yells into Bill’s earpiece during a pause in the next debate.

“How can I be rude?” he demands. “I only have 30 seconds left.”

“Well, that’s your opinion” is one of his best blows after the bell has rung. As if he weren’t presenting his opinions.

O’Reilly sees his debating style as like a boxer, punching and jabbing, looking for openings. But he is not totally merciless. That is to say, when somebody is down, he doesn’t kick them in the kidneys. He will go to a neutral corner. “Most people I’ll save when I feel them going down. I’ll pull back. I don’t want to humiliate anybody.” But he made exceptions in the cases of James Wolcott of Vanity Fair and Mike Kinsley of Slate, both of whom he felt had written some low blows about his family.

O’Reilly’s favorite performance came during the Bush interview during Primaries 2000. “They really didn’t want to do the interview,” O’Reilly says as we walk out of the studio. “It was Super Tuesday Eve, and they knew they had to win California. The Factor has an enormous audience in California and New York. So they made a decision. All right, we’ll go in with this animal O’Reilly. We’ll talk but we think we can control him.

“Bush came in with ten talking points, compassionate conservatism, whatever he was throwing out. But my job is to blast him out of it as fast as I can. So I came up with the hardest question he had ever been asked: ‘Governor, during the debates you said Jesus Christ was your personal philosophy and model. Whether you believe he’s God or not, certainly his philosophy has been incorporated into Western civilization for 2,000 years….’ Now Bush is loving it, and I say, ‘But if he’s your philosopher model, what do you think Jesus would think of you executing all those people in Texas?’

“I thought about that question for a good two or three hours. You could see all the rehearsed answers go out his ear. Shoooom! Because he’s fighting for his life, he’s on the record, and since Jesus was a victim of capital punishment, I thought [Bush would] have a pretty good point of view on it. So you know he danced around and this and that. But I wouldn’t let him go, and finally he said, ‘I really don’t know what he would think. The New Testament doesn’t really address it.’ And I said, ‘Well, I don’t know, I think Jesus might disagree on this one.’

“It was good TV, and it was the best interview he’d ever done. Because he forgot everything he was supposed to say, and then we just talked. He’s not stupid. His syntax was perfect, because he wasn’t parroting everything he was supposed to say.”

O’Reilly is a very happy man. He is in a dream situation. Ailes, the coach, has given him the ball. Bill is the quarterback calling his own plays. The crowd is yelling its head off. “Go, Bill, go!”

“People don’t realize I can never leave this job. That’s the down side. You’re always thinking, What are you going to do tomorrow, next week? And you always gotta be looking for different things and building up your frame of references so you don’t look like an idiot. My orders are always get the smartest people out there to talk to. I’m not like George Foreman booking the palooka out of Hershey, Pennsylvania. I want the MIT Ph.D., if he can speak against me, because it makes it exciting to bring the smart ones on.”

Still, he can only live the dream because of ratings. They are the oxygen that keeps it all going. Without the numbers, he’s on the heart-and-lung machine. The suits would be all over him. They would take away his soapbox. He would be just another frustrated, angry drunk, throwing beer cans at the screen as the steelworkers used to do to Howard.

So all that his enemies have to do is get people to stop watching.

The story of Bill O’Reilly got a lot more scandalous as time went on, and we feel both an obligation and a joy in avoiding debate on that evolution, having determined such discussion to dissuade from the historic value of this Legacy article. On an entirely safer bit of historic value, though, one might reconsider the Palm Pilot. For those that had one, this will almost certainly draw from your memories equal amounts of joy and frustration as you recall working with one. Inasmuch as the name these days sounds more like an adult movie feauturing only solo performers than some technolgocial marvel, those unfamiliar with the object should not feel too left out. It turns out people still buy them on Amazon, even though way back in 2011 the eventual brand owner HP discontinued the Palm line. If nothing else, this fact serves as more data supporting the thesis that people are weird.

We should probably also mention one final bit of a history lesson, it seems to us. When Fox fired Bill O’Reilly after a deluge of allegations, they filled his time slot with … Tucker Carlson. So there’s that.