Having grown up in the shadow of one of the greatest directors in movie history, Danny Huston has managed to become — as an actor and director — his own man. Which is exactly as his father would have had it.

Danny Huston: His Father’s Son

As a director who frequently had to put up with the barbs of critics comparing his work unfavorably to that of his father, the great John Huston, Danny Huston quickly learned the merit of ignoring his own press. He’s equally serene now that the pendulum has swung back the other way and the reviews of his acting gigs are, for the most part, positive. Critics — among them A.O. Scott of the New York Times — may be likening his late-blooming acting skills to those of a young Orson Welles, but Huston bats away such comparisons.

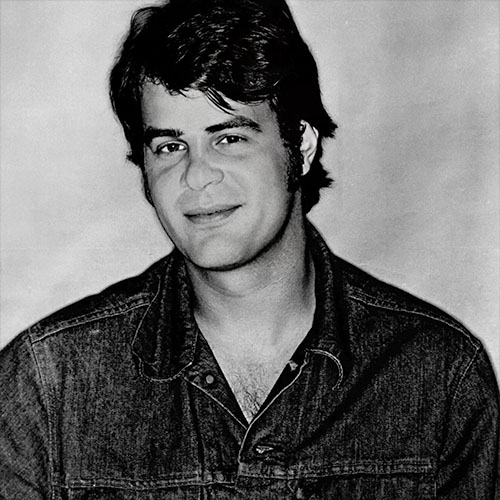

Dressed in a rumpled white shirt and slacks, his head topped with a curly mop of dark brown hair (often slicked back in publicity shots), Huston, 42, certainly does not look as if he spends half the morning in front of the mirror, something that will no doubt comfort female members of the Huston clan. According to the British newspaper the Independent, Zoe Sallis, Danny’s mother, was not all that keen on the idea of him becoming “a vain male actor,” and his half-sister Anjelica Huston declared recently in the Sydney Morning Herald, “I don’t think [acting] is a healthy life for a man, in truth…. Men shouldn’t be allowed in front of the mirror too much, it’s better suited to women.” The article did not specify to whom she might have been referring, though it’s common knowledge that the actress spent several years stepping out with Jack Nicholson.

With that kind of familial opposition, it’s not surprising that Huston resisted the lure of acting until well into his thirties. “As [Robert] Mitchum said, ‘There are no actors, only actresses,’” Huston declares with a grin. “I thought it was a kind of silly job for a man, but I suppose this was as I was entering into my manhood, so maybe I was a little sensitive regarding that. Not that I lacked any respect for acting, because I knew and admired people like Mitchum… but I just felt it was a slightly self-involved profession to choose…. One of the reasons I really got into it was to observe other directors at work and see if I could steal anything or borrow anything from them.”

Huston’s first role was a bit part as “Barman 2” in 1995’s Leaving Las Vegas, which was directed by his friend Mike Figgis, who says, “When Danny mentioned to me recently [that this was his first role], I told him, ‘But you told me you’d acted in other films before.’ I’d known Danny for a while, and he is a natural actor. He’s watched actors and filmmaking all his life, with the best. To me it would have been odd if I’d discovered he couldn’t act.”

On a beautiful sunny morning at the Hotel Gritti in Venice, Huston and I are trying to make ourselves heard above the church bells and motorized gondolas. Huston is in high spirits, happy with the reception of the film Birth and full of the joys of fatherhood. His British wife, Katie Jane Evans, recently gave birth to their first child, a girl. In Birth, directed by Jonathan Glazer, whose first feature film was the excellent Sexy Beast, Huston plays a businessman about to marry a woman (Nicole Kidman) who falls in love with a ten-year-old she believes is the reincarnation of her dead husband. In one scene, Huston’s character, utterly bewildered by his fiancee’s behavior, grabs the boy and tries to teach him a lesson by spanking him. Huston brilliantly conveys the point at which an eminently logical man cracks under the pressure of a ridiculous situation utterly beyond his ken. It was an opportunity for Huston to play a scene in which he needed to impose himself physically, something his film roles up until then had not required. “[The scene] was very exciting,” he says, “and I knew I was going to explode at some point so I could keep the control all the more, which is something that I love, knowing that there would be a crescendo.”

Acting in Birth also gave Huston the opportunity to catch up with Lauren Bacall, who plays Kidman’s mother. Bacall, along with her husband Humphrey Bogart, was a frequent visitor chez John Huston. She told Danny an anecdote about The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which won Oscars in 1949 not only for John Huston (Best Screenplay and Best Director) but also for Danny’s grandfather, Walter Huston, for Best Supporting Actor. “Apparently my father turned around to Bogie and said, ‘Bogie, I think we’re making a good picture here,’ and Bogart said, ‘Shut up, John, it’s just a fucking western.’”

The interesting thing about Danny Huston as an actor is that he’s not afraid to tackle the unsympathetic roles that frequently scare off others. In Anna Karenina (1997) he played Anna’s brother Stiva, among the most licentious of Tolstoy’s characters; in Eden (2001) he was downright venal; in Figgis’s split-screen Timecode (2000) he was a coked-up security guard; and in Ivansxtc (2000), he played a Hollywood agent whose life fatally spirals out of control. A couple of years ago, Huston was up for a more conventional part as Detective Joe Friday in ABC’s revival of Dragnet. In the end that didn’t work out.

“I’ve spent enough time in England so if you put me on a deck chair and put a drink in my hand, I think I’ve robbed a bank.”

“With Dragnet,” Huston says, “I have the sense that they were looking for something pretty standard, and I said a few things that made their blood run cold. So it was an amicable sort of parting. I like characters that are not perfect. I have a particular love for life’s losers. I like stories where they try valiantly again and again and still lose. It’s really the quirks and imperfections that give me a feeling of affection. The important thing for me is not to stereotype them or look down on them, because they are trying to succeed. I mean, the security guard in Timecode thinks he’s the shit, man. He thinks he’s really groovy and got it all together. But when shots are heard and things go wrong, his heart goes aflutter.”

Huston’s vernacular is a curious hybrid of West Coast Americana and English private school. He has been a resident of Los Angeles for several years now, but was educated at expensive schools in England, where his mother lives. What his speech does have is a great timbre, a sped-up version of his father’s languorous drawl, a perfect voice for cinema. It was used to good effect, with an added southern twang, in Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator, the Howard Hughes biopic starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Huston plays Arkansas-born Jack Frye, the president of TWA who befriended Hughes, then persuaded him to buy a majority in TWA and take over the company. “There was a scene I worked on with Leo where basically we tried to get through eight pages of dialogue in under a minute, and when we finished, Marty — who as you know has a certain pace when he speaks — was like, ‘Shit, man, that was fast.’ Leo and I were delighted with ourselves.”

The role was a change of pace for Huston in that it forced him to do some concrete research, as opposed to just relying on his instincts. “A lot of my dialogue has technical dimensions which I have to connect with. When these guys say things like ‘XF-11,’ it’s the same way I suppose if you’re a car lover you say the word Ferrari. It’s loaded with appeal, it’s kind of sexy, it’s not just talking about airplanes and altitude.”

Huston had another meaty role in a film adaptation of John le Carre’s political thriller The Constant Gardener, Brazilian director Fernando Meirelles’s English-language follow-up to his Oscar-nominated City of God. Gardener required a switch of accents. Huston played an English diplomat mixed up in the pharmaceutical business who says things like, “It’s a harsh commercial world,” and, “Those patients would have died anyway.” To prepare himself, Huston had meetings with folks from the British spy agencies MI-5 and MI-6, and in the City, or financial district, of London. “Their careful choice of words is fascinating,” Huston says. “There was somebody they were insulting — well, not insulting, but somebody they didn’t like — and we pried a little bit to find out what they thought of him, and the reply was, ‘Well, we always like to see the best in people,’ which was basically calling the guy a complete cunt. So I tried to understand these sort of upbeat mannerisms and how they could be so extraordinarily polite while basically slaughtering somebody.”

Roles in these multimillion-dollar features are a far cry from the kind of independent projects on which Huston cut his acting teeth, like his breakout role as Hollywood agent Ivan Beckman in British director Bernard Rose’s little-seen but exquisitely made Ivansxtc. The film is a faithful, though contemporary-set, version of Tolstoy’s novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich. It’s possibly Huston’s finest hour to date as an actor. He is utterly believable in the part, at turns charming, charismatic, and brave, but also increasingly pathetic — like all golden boys gone to seed. Rose wrote the part of Beckman with the hedonistic Hollywood agent Jay Moloney in mind. In a tragic denouement, Moloney, onetime agent to Sean Connery and Kevin Costner, died at age 35 (allegedly committing suicide), just as Rose was about to complete the film. “Danny, like Jay Moloney, has those rare unfakeable qualities: charm, charisma, and an unbridled joie de vivre,” says Rose. “He was our first and only choice to play the part of Ivan. When he read Ivansxtc, he immediately understood it.”

For Huston and Rose, shooting the film in digital on a minuscule budget around L.A., where they were both living, was a revelation. “This excited Bernard and me tremendously because we didn’t necessarily have to ask anyone permission to make a movie,” says Huston. “Both Bernard and I have suffered — not to blame anybody, maybe because of particular tastes — with meeting after meeting with the studios trying to get our projects made. All that long-winded, strenuous waiting was obliterated by getting a camera and pressing a button.” Huston gives credit to Rose’s business partner, Lisa Enos, who produced and acts in Ivansxtc, for making the project happen at all. “Basically it was many nights of Bernard and me moaning about our predicament [of not being able to get our films made], and his girlfriend at the time, Lisa, said, ‘Jesus Christ, will you please shut up! I’ve made documentaries; I’ve never had to ask anybody. Why don’t you get a video camera and shoot?’ And we were like, ‘Sweetheart, it’s much more complicated than that. You don’t quite know what you’re talking about.’ Anyway, Bernard tried the camera out, we did a couple of tests, and we thought, You know what, we can do it.”

Forced to identify which Hollywood folks he hangs with, he admits to a kinship with Englishmen Rose and Figgis. “There are a lot of interesting Brits who come to L.A. after they’ve made a film or two to kind of exploit their talents, so there’s always an interesting pool of people and always a fresh batch. The L.A. crowd is kind of set in their ways, and they make a certain type of film and they continue to do so. That might be interesting, but it’s refreshing to see new faces.”

Huston, who describes himself as “married, [with] a child and a slightly bourgeois house with two cars and a garage,” enjoys living in Hollywood. “My sense is, I’ve spent enough time in England so if you put me on a deck chair and put a drink in my hand, I think I’ve robbed a bank. I mean, like, fuck, how did I get here? This feels good. People say that L.A.’s superficial, but you know, I think only superficial people can’t be superficial.”

After attending the London International Film School, Huston came to Hollywood and directed Mr. North (1988), Becoming Colette (1991), The Maddening (1995), and several television films without quite winning over the public or the critics. Perhaps he was a bit young; note that John Huston was 35 when he directed his first film, The Maltese Falcon, while Danny was only 25 when he directed Mr. North.

Danny certainly feels he has a lot left to offer as a director. “I’m itching to go back to directing, and I’ve written a couple of screenplays,” he says. “And I think now I can approach it in a different way as far as casting goes. I might be able to rope in some of my fellow thespians and get some financing that way.”

“The L.A. crown is kind of set in their ways, and they make a certain type of film. That might be interesting, but it’s refreshing to see new faces.”

“A lot of times it’s really hard to get a project going as a director,” he continues, “because you’re not out there unless you’re schmoozing at parties or you’ve got some big studio behind you, but it’s wonderful to be able to say to somebody you’ve been working with, ‘I’ve written this screenplay, and in your own time check it out, and if you like it, let me know and maybe we’ll make it together someday.’”

The two projects that Huston says he will make when the time is right hark back to the kind of south-of-the-border shenanigans John Huston was so fond of recreating in films like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, and The Night of the Iguana. One is an adaptation Danny has written of Kent Harrington’s cult novel Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). The other has a romantic discovery attached. Rummaging through a trunk, Huston found an unfilmed script of his father’s called Amparo, about a burned-out screenwriter who goes to Mexico and falls in love with a young prostitute. It was, Danny says, “like discovering my father’s treasure, his jewel. But it was a rough jewel, with my father’s handwritten notes, so I took it upon myself to polish it.”

Huston was all set to shoot Amparo in 2000, but Bluevision Media, the Hollywood company offering the $5 million budget, suddenly dissolved, and that was that. Huston marvels at the way his father managed to work the Hollywood system to his advantage to get films made — often films with a highly personal vision of the world. “I’ve always admired films which worked within the Hollywood system that seemed like they had happy endings, or seemed to comply with whatever censorship was going on at the time, when in actual fact there was something darker underneath the surface. And you didn’t really have to scratch that deeply to find it, but you could kind of fool people into thinking that it was something else. I’ve always been interested in how directors have been able to work within Hollywood’s constraints and pull that off. I think that to make a film that works on those levels is really quite an achievement, and my father was able to do that beautifully. He played a form of poker with these executives, and played an extraordinary game where he made the system work for him. I remember there was a story about [producer] Sam Spiegel working on the set of The African Queen and my father had the entire African tribe in the Belgian Congo greet Sam Spiegel, lift him up into the air, and carry him through the village for about half a day. Spiegel couldn’t wait to get the hell out of there.”

Danny Huston, who was conceived during his father’s production of Freud and born in Rome during the filming of Night of the Iguana, is, not surprisingly, steeped in his father’s films. Asked if he has ever felt like he was living in his father’s shadow, Danny hesitates a moment before replying, as though chewing on an old chestnut, “Yes, I felt that a couple of times. There was a review for Mr. North [in Variety] which said John Huston passed Danny the baton, and he dropped it. You read those kinds of things and you go, ouch. But I feel that my father is such a giant in the film world that he really keeps my aims high. And, yes, I feel at times I’m in his shadow, but he’s kind of protecting me from the harsh rays of the sun, and at times it’s quite comfortable.”

That’s not to say Huston isn’t his own man. While it’s clear he listened hard to his father’s advice, he did not always follow it. “I remember saying to my father when Bertolucci was shooting [The Last Emperor] that I’d love to be working on that film, that I’d do anything, I’d be a runner, absolutely anything, and he said [in a great impersonation of his father], ‘I don’t know if you can do that, Danny, you’re a director now.’ But I’ve never agreed with that. Just because you do one thing doesn’t mean you can’t do others.”

This certainly meshes with Figgis’s experience working with Huston in three films (Leaving Las Vegas, Timecode, and Hotel). “There are a few actors I just like having around,” says Figgis. “Danny stayed on with Hotel all the way through the editing process, without being paid, and helped me think my way through a lot of footage.”

Now that’s a man who loves filmmaking for its own sake, and the rest of Huston’s career will surely reflect that passion in equal measure.

As with most movie people, IMDB tends to be the place where one might get sort of a 30,000’ view of a career. Also, the established ones, at least of a certain generation, tend to have fairly week and rapidly aging Instagram accounts. That said, we’d encourage the typical, albeit more time-consuming, way to get to know any creative. Watch their work. Enjoy the acting, but give yourself a chance to really absorb the directing. Give an hour and a half of your life to “The Last Photograph” when you get a chance.