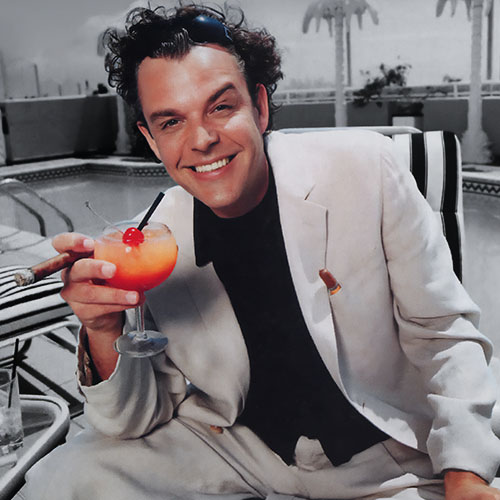

The man who made selling rock-‘n’-roll to Middle America look easy.

America’s Band Leader

Dick Clark changed it all.

I was 13 years old when, on a summer day in 1955, music history was made. To the cynics — anyone older than 25 — it was considered a fad, a quirk, like so many other events during the Eisenhower reign in America. You remember — or, if not, your weird grandfather with the long sideburns and longer strands of hair covering his ever-increasing bald spots must have told you all about — those days of hula-hoops, of stuffing as many friends in a telephone booth as possible, of students neatly dressed in freshly ironed shirts and thin ties — underneath the black leather jackets with eagles on the back that you took off as soon as the bus pulled into the schoolyard. But July 9, 1955, was music’s equivalent of the French Revolution — the day “Rock Around the Clock,” by Bill Haley & His Comets, became the No. 1 song in America. Bye-bye, Perry Como; hello, Elvis.

Maybe the rock-‘n’-roll hits on the heels of “Rock Around the Clock” — made even more popular by the success of The Blackboard Jungle, a film about how America’s youth were going to hell in a handbasket — would have been nothing more than a short-lived fad of music if it hadn’t been for a man named Dick Clark, who hosted a local Philadelphia ABC television show called “Bandstand,” which because of its success soon got called “American Bandstand.” Clark, born in 1930, was only 26 years old and a music man who envisioned a world of youth and music very different from “Leave It to Beaver” and Frank Sinatra crooning songs his way. Clark saw the commercial potential of this new culture beyond Philadelphia. He appealed to the guys in the sharp suits in New York City. He recalls:

‘The show “was all faked out. If we’d done it raw, it would have been shot down.”’

I kept hammering away at ABC, but all I got was: “Hey, thanks, but don’t call us, we’ll call you.” Finally we wore them down, and we were given a seven-week trial on 67 stations. It was so successful we received an award: “America’s Number One Daytime Show …” Today we would never have made it. Back then you had, what, two-and-a-half networks? Today you turn on the television and you’ve got dozens of networks and cable stations to choose from. Timing was on our side.

Watching reruns of those early days of “American Bandstand,” it seems so clean-cut, embarrassingly innocent — a time that doesn’t exist anymore. I don’t think I ever saw a tattoo or cleavage on the show. Also it seems to me that the kids on the show were the real celebrities. Am I exaggerating?

These kids just came by, stood on line, and got picked for the show. These kids were special. I mean, those kids — long before Andy Warhol thought of the idea about everyone and their 15 minutes of fame — were in national fan magazines and getting 15,000 pieces of mail sent to the studio. In fact they’re now doing a film that we’re co-producing with Danny DeVito and the “Bandstand” regulars. I may have been young, but I knew that I wasn’t the star of the show. Keeping the focus and camera on the kids was the most important thing for me to do. If there is one secret to the success of “American Bandstand,” it was my taking a back seat to the kids.

Looking back 40 years, I remember rushing home to watch the show. Hey, there were a few girls on that show I would have left home and family to marry. On the other hand I recall some of the girls in school talking about some cute guys with Elvis kind of buns. So it would seem to me that while you had dozens of clean-cut kids on the show, there was also a pecking order, the stars who were always in the camera’s lens.

I’ll answer that first, but then let me go back and offer a clearer explanation about what you call “clean-cut kids.”

There was a pecking order on “Bandstand,” like everything else in life. Bob and Justine [“Bandstand” regulars] were probably the most famous couple we ever had. They’d dance together, and people would fantasize about what they thought was a hot romance. It was a daily soap opera without a script. People at home would watch, and when they [Bob and Justine] weren’t dancing together, would make up their own thoughts: “Oh God, they must have had a fight!”

Trust me, it was really primitive television. However, it was a clean-cut show; the boys wore coats and ties, but it was all faked out. We knew that to get rock-‘n’-roll music accepted and not thrown off the air, for parents to control their outrage, that if the kids looked nice it would pass. And it did. It was almost a collaborative effort on our part. The kids knew what it was all about. It gave a patina of purity to this thing when we were playing records that couldn’t get on most airwaves. Look, I’m not being defensive about this, it was simply being clever. If we had done the show in its raw state, parents and politicians would have shot it down.

I think people now under the age of 40 have no idea what was going on at the time. Films were made about rock and roll, but rock and roll was equated with juvenile delinquency, indecency. Rock and roll was evil, but there was something else going on in rock and roll that had nothing to do with juvenile delinquency. It was called “payola” — kickbacks to play and plug songs. How did you stay above it?

I didn’t stay above it. I got caught right smack dab in the middle of it, because I was so well known. I was the best-known disk jockey in the country at that point, and I was on television. The thing that always fascinated me and made me a little jaundiced about politicians was that they came chasing after me because I made quite a bit of money, a lot for those days. And in the eyes of politicians the only way you can make that kind of money at 26 is by being on the take. It’s the way they think. They were aghast to learn that I was a businessman. I owned record companies, managed talent, owned copyrights. I did everything in the world to make money, honestly and legitimately.

The perversity of it all was that I was not on the taking end, but on the giving end. Since then the laws have changed, but at the time we’re talking about I broke no laws. And what is so sad is what the federal agencies do when they’re wrong — disrupting your life, invading your home, and worse — and then “Oops, you’re a fine young man and you’re not to blame for any of this.” Perhaps not, but for two years my life was in disarray. Not to mention obscene legal fees.

Few people know about your quiet activities to undo America’s perennial racial divide. Tell us a little about your efforts.

Radio music was awful to black artists. So to get black [race] music on white stations, white artists would record or “cover” the songs. Pat Boone was more acceptable than some African-American performer. But somewhere in the mid-fifties some disk jockeys began to play so-called race music, and the kids went wild over it. On “Bandstand” we would play Fats Domino records, Sam Cooke, and occasionally play a [white] cover of their music. But we learned it was the Fats Domino and Sam Cooke versions that were popular. We played The Crows before The Crewcuts, and the kids loved it. It was one of the main reasons “Bandstand” was successful. Radio was living on another planet. Here we had radio shows playing only white music and the shows were going bust. But there we were, playing on “Bandstand” — right across the hall from the radio studio — all these black artists and enjoying television’s greatest afternoon audiences in the country.

Would you call yourself a pioneer? A racial activist?

We did it — “we” including Tony Mammarella, my producer — because it was the right thing to do. And we did it without incident. Not only performers, but the kids were from all backgrounds. Nobody ever got outraged, nobody got hurt. There were no riots, we received no outraged telephone calls. And this is the miracle: It was during the social atmosphere of sit-ins and lynchings, and you had people of different races entertaining other different races in the same room where different races were socializing. Best of all, [people of] every race or ethnic group you could think of were in front of their 12-inch black-and-white televisions, watching it all happen. Still, don’t confuse me with some wide-eyed activist preaching to the masses. We simply didn’t make a big deal out of it. There were no press announcements, no marchers in front of the studio, and no nasty posters. It was daytime television, kids dancing, laughing, partying, who cares? I cannot explain why nothing [bad] happened. Thank God.

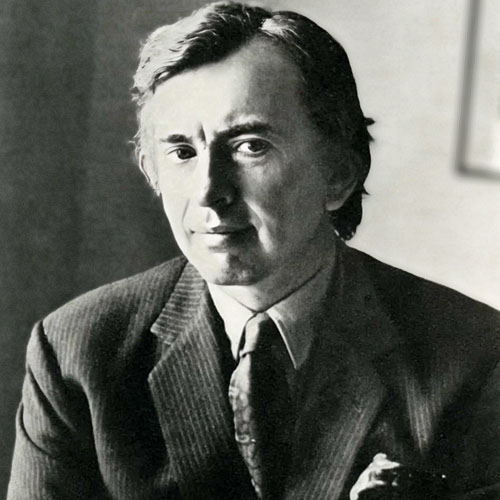

The Dick Clark, readers, whom you still see on your network or cable station is precisely what you get. He’s that eternal-looking Ponce de Leon, the face of youth and vigor, the kind of guy you’d enjoy swapping tales with over glasses of beer It’s difficult to locate bitterness or anger in his heart — given the stab-thy-neighbor-in-the-back ethic of show business — because he’d rather say nothing than speak evil of his critics. However, there’s an exception to the rule. Clark believes there were and are some very famous entertainers and highly regarded Americans out there who chose to mislead the masses. These sworn enemies — spokespersons for censoring and destroying rock and roll — belong to the approaching — Social Security generation who hate youth and its accompanying joy

I lived through the “hate rock and roll” days. It was a strange reaction, because it came from different quarters. It came from the religious community, of course. It came from jump-on-the-band-wagon politicians to win elections. Parents were outraged because the music was alien. And then there was the music-publishing industry, which was losing its income to these unwashed, musically uneducated, and very young people who didn’t belong in their society. We had ASCAP versus BMI. Most of the kids had to join BMI, because ASCAP wouldn’t accept them. So ASCAP looked to destroy these kids and BMI, and brought out diverse people to say that rock and roll is terrible. [The late actress] Helen Hayes joined the wolf pack, and that late, great defender of the First Amendment Tip O’Neill [Boston pol, later Speaker of the House] issued a quote I keep on my blotter: “Rock and roll is a type of sensuous music unfit for impressionable minors.” There were others, like Sinatra and Mitch Miller, joining in the voices of censorship.

“I asked Grace Slick if she recalled her first national TV appearance. ‘Dick” she said, ‘I don’t remember anything about the Sixties.’”

Who are the greatest rock stars of all time — the musicians who will always be recalled as the stars of their decades? (Clark rolled his eyes when I insisted, but he finds it difficult to say no to a guest.)

Well, the fifties belong to Elvis. However, and only by a few years, there were Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley. Soon after, in the sixties, you get the Beatles, and then Elton John in the seventies, and Michael Jackson in the eighties. In the nineties, hmm, maybe Garth Brooks.

Drugs have always been part of the rock scene. Are things getting better or worse?

You’ve got the same problems today. When the Jefferson Airplane came on “Bandstand” they were quite ravaged. Years later I asked Grace Slick, did she remember the show. It was the band’s first national television appearance. She looked at me and said, “Dick, I don’t remember anything about the sixties.”

Now it’s the nineties. Do record companies today have a responsibility for watching out for their clients, their artists who have drug problems? I don’t think that’s ever going to happen. I wish it would, but the business is driven by the bottom line. If the hottest lead singer of the hottest group is a junkie, they just want to keep him alive. They don’t care if he cleans up his act, gets straight. That would kill the music. You know, back in the early “Bandstand” days I don’t know how many kids in the studio were doing drugs or smoking pot. Undoubtedly some of them were. We didn’t deal with it much, but many of the artists were stoned. I was talking to the lead singer of a group where the drummer nodded out. I don’t know what he was on, but this was not the best portion of his day. It was nap time. But you see, I was too old for the drug generation, so I could never come to understand it. My heart goes out to all those who allowed drugs to end their young lives so early.

What about a related issue — censorship? You must find certain lyrics offensive. Would Dick Clark The Producer censor them?

You can’t censor artists, because it becomes pervasive. My brother died in World War II, fighting in Germany, and he and hundreds of thousands of others were killed to make this a free place. I believe in that. I believe in the First Amendment. But there is another alternative — self-restraint, education, and discretion. The world’s not perfect, but we can work in that direction.

Meeting your beautiful wife, Kari, made me think of the great romantic songs of my generation, in the fifties….

You idolize the fifties because of your age. That’s very, very common. In terms of music, in terms of everything, you atrophy, you freeze. You return to the music you grew up with. I’ve been through it all, by good luck and good fortune. I went through the fifties, sixties, seventies, eighties, and now the nineties. You have to stay current, but at my age it’s difficult. How to stay current? My wife is the greatest thing ever, and got me a 2,000-play jukebox at home. So, because of her, whatever my mood, I can pick jazz, Brazilian music, R&B, pop, and on and on. Now you know it’s Kari who’s keeping me young and sort of still cool.

Clark’s new book, American Bandstand, has just been published by Harper-Collins. For anyone of my generation, it’s a revisiting of the wonder years. For a younger generation it’s a visit to why mom and dad keep yapping about a sacred cow pasture called Woodstock. It’s also about a man who made life a bit more pleasurable for millions of us who love rock and roll. As long as we have Dick Clark, the lines in “American Pie” are wrong. We miss Buddy Holly, but the music still lives.

There are many of us still around that cannot remember a Saturday morning of our youth without American Bandstand. Then, of course, we went off to college where we pretty much cannot remember a Saturday morning at all. … Wouldn’t you just love to know what Dick Clark would think of where Rock actually Rolled?