The major leagues’ most controversial umpire finally tells the whole truth about is double life.

Behind the Mask

Growing up in Massachusetts, Dave Pallone dreamed of playing major league baseball. When a high school injury snuffed that dream, he discovered umpiring. After a long apprenticeship in the minors, Pallone became a major league umpire by crossing the picket line in the umpires’ strike of 1979. For that transgression, he paid a brutal price. Over the next ten years, union umps ostracized him relentlessly as a “scab.” They refused to associate with him off the field, trashed his equipment, spread malicious rumors about him, undermined his work in games. A closeted gay, Pallone wore not only his umpire’s mask, but also the mask of his secret personal life. His only island of sanity was a three-year relationship with his lover, Scott. But that, too, was ill-fated; the day after Thanksgiving in 1982, Scott was killed in an automobile accident.

Pallone attracted public attention on April 30, 1988, when Pete Rose shoved him during a Mets-Reds game, igniting one of the most controversial incidents in baseball history. Rose was suspended for 30 days and fined $10,000 — and Pallone lost his only chance to work a World Series. On September 15 baseball suddenly forced Pallone to take a leave of absence. Six days later his career — and reputation — were permanently ruined. The New York Post ran a story announcing the “bombshell revelation” that Pallone was under investigation in “the Saratoga sex scandal” involving teenage boys.

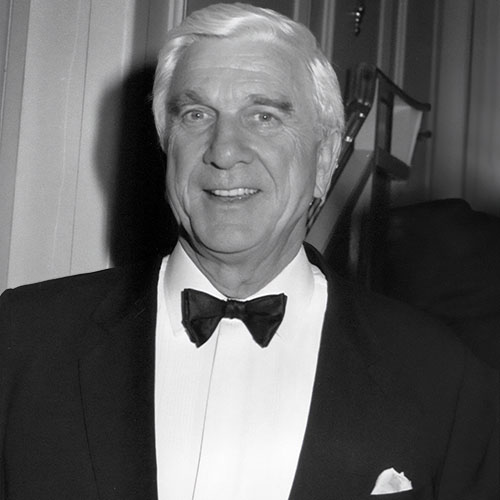

Although the D.A.’s office in Saratoga Springs, New York, investigated Pallone, they never charged him or acknowledged the investigation. But that wasn’t good enough for baseball. In late November A. Bartlett Giamatti, then president of the National League, informed Pallone that the league was not renewing his contract. Giamatti cited low ratings, an old rumor that Pallone “picked up” a man in a Cincinnati bar, and alleged involvement in the Saratoga sex scandal. Pallone insists that it was all a smoke screen, and that baseball was so intent on getting a gay out of the game, they didn’t care about the truth.

Pal/one’s shockingly honest book, Behind the Mask: My Double Life in Baseball (Viking, July 1990), written with author Alan Steinberg, takes a close look at how baseball is really played and officiated, and is bound to raise a controversy about the national pastime’s deeply ingrained homophobia. This excerpt begins in September 1988, after Pallone had learned that baseball was investigating his alleged involvement in the Saratoga Springs incident.

For most of the first two weeks of September, I juggled the pressures of a pennant race with the stress of worrying about why baseball was investigating me and how I could clear my name of something I hadn’t been accused of before something terrible happened. I was in a holding action; I just kept rationalizing that as long as no one contacted me directly, I must be okay. Then on Wednesday, September 14, things changed. I had just arrived in Philadelphia for the second game of a three-game series when Eddie Vargo [supervisor of umpires] came into the dressing room to tell me that Giamatti wanted to see me in his office the next day at 10 AM.

The idea of an emergency meeting worried me, but I assumed it was baseball-related. Since I had a “businessman’s special” afternoon game on Thursday, I called Giamatti’s hotel to find out what was going on. He wasn’t in, so I left a message for him to call me at my hotel. He did call-around midnight. I told him my situation and asked if we could reschedule. He said, “No, David. This can’t wait. I need to speak to you tomorrow.” That got me anxious: “Well, what is it about? Is it what we talked about in July-the investigation?” He said, “Yes, I’m afraid it is.” I said I’d take the first train to New York in the morning.

I was upset, apprehensive-I felt like I was heading into a war zone. So I called my lawyer, Joe Fiore. He suggested going with me, but I said I’d rather go alone and let him know what happened. He advised me to be careful about what I said. “Don’t worry,” I told him. “I have nothing to hide.” When I hung up, I felt like I needed to talk to someone else. I phoned [fellow umpire] Paul Runge and told him what the meeting was about and that I thought something bad was going to happen. “I’m really scared about this thing,” I admitted. “It’s too secretive. What can I do about it?”

Paul said, “Did you do anything wrong?”

“Absolutely not. Jesus Christ, I barely know those people!”

“Then don’t worry,” he said. “If you didn’t do anything wrong, there’s nothing to worry about.” That was his general attitude in life: There’s nothing to fear but fear itself.

It calmed me down a little — but I couldn’t sit still in the hotel. So I went out to a gay bar called Key West to have a few drinks and collect my thoughts. I drank beer at the upstairs bar, feeling depressed and alone. The only other times I had ever felt this despondent were when my parents died and when Scott was killed. More than anything else, I needed to talk to someone who loved me. But there was no one in my life, so I sat there dwelling on the things I feared. I envisioned being forced out of the closet in a way I’d never dreamed of, and losing my career and my reputation as a decent human being. Then I thought about my mother — the day she drove me to the baseball camp, how proud she looked when I completed umpire school, how sure she was that I had chosen the right profession. And I thought of Scott — the first time we made love, the times he came on the road with me, the great mood he was in the night he died, when he put on my brand-new jersey and flashed me that smile that always said, “Hey, don’t worry. Everything’s going great.”

I dragged myself into my hotel room around 2 A.M… but needless to say, I couldn’t sleep. When morning broke I was worn out. On the train I was so nervous, and it was so humid outside, I sweated profusely all the way to New York. I arrived at the league office, soaked and drained, at exactly 10 A.M. When I entered Giamatti’s office, I was surprised to find Lou Haynes there. He was the league counsel-an instant danger sign. Giamatti’s face was creased with concern. He said, “David, we have a problem in Saratoga Springs, New York. They’re conducting an investigation into a homosexual sex scandal involving teenage boys, and the assistant district attorney wants to talk to you about it. His name is Thomas McNamara. Do you know him?”

I said, “No. And I don’t understand. If there’s a problem, how come they haven’t come to me?”

“I don’t know. But they came to us, and you must contact this man.”

“I don’t even know what this is all about. I’ve heard rumblings about it, but I am not involved in any way whatsoever.”

“Nevertheless, you need to attend to this. The season’s almost over, so we feel you should take a leave of absence, with pay, and take whatever time you need to get it straightened out.”

“Jesus, I don’t want a leave of absence.”

“I’m sorry, Dave. Either you take it or I have to give it to you — and I don’t want to do it that way.” He showed me two letters dated September 15 — one granting my request for a leave and the other directing me to take a leave. “I had both letters written up for you,” he said. “But I think it will be better for you if you take the leave voluntarily, rather than if I give it to you.”

I was confused. I said, “Well, Jesus Christ, I can’t make this decision now. I have to talk to my lawyer.”

He then escorted me into the conference room and showed me the phone. “Use it for as long as you like.”

I called Joe Fiore and explained the options I was offered. Joe said, “Take the voluntary leave.” I said, “You think it’s the right thing to do?” He said, “Yeah, take it. I don’t see any problems with that.” I wasn’t sure, but I figured I wasn’t paying a lawyer not to take his advice. So I went back into Giamatti’s office and told him I would take the leave.

“Good,” he said. “I’m glad you made that decision.” He gave me the appropriate letter, and we agreed that if anyone inquired about me, the league office would say only that I took a leave of absence for “personal reasons.” Then I blurted out, “I can’t believe this is happening. What about next year?”

Giamatti said, “Let’s not worry about next year. Let’s just get over this first.” On that note I left. I had second thoughts immediately. When I told Paul Runge what had happened I felt even worse, because he was against the leave. He said it would look like I was guilty of something. I said, “Well. all I know is I’m not. And I hope this doesn’t affect our friendship.” Dead serious, he answered, “You don’t make it easy. Every time you take a step, the whole world falls in behind you.”

Little did I know that in just a few days I would feel like the whole world had fallen on me. On Friday, knowing I would need an attorney licensed in New York, I asked Joe Fiore to refer me to the best one he knew. He lined me up with E. Stewart Jones. Jr., a renowned defense attorney from Troy, near Albany. A meeting was arranged for the following Wednesday in Troy, and another one was scheduled for Thursday between Jones, Fiore. myself, and Assistant D.A. McNamara at McNamara’s office in Saratoga Springs.

My main concern was to give McNamara my side of the story before my name got leaked to the press. I knew that if the papers found out I was being investigated in a homosexual sex scandal, I was dead. They would absolutely crucify me. Most people believe what they read. Innocent or guilty — it doesn’t matter: “Well. the paper said so. It must be true.” Even if you didn’t do it. once the papers say you did it-or even that you’re suspected of doing it — you’re through. It raises too much doubt in people’s minds. But if you’re cleared and they print that. does anybody see it or remember it? No. They only remember that you were linked to the problem one way or another. I understood the mechanism, because for ten years I was “Dave Pallone. the scab umpire.” and now I was “the Pete Rose guy.” Those labels stick. That’s why my thinking was, Christ almighty. Imagine what I’ll be labeled if this gets out.

In the meantime, all I could do was lay low and wait until Wednesday. But the big news that weekend was that Dave Pallone didn’t work his scheduled games in Cincinnati. Because of the Rose thing, that was a very big deal there. The press interviewed [my crew chief, veteran umpire] John Kibler. they called the National League office, and they tried to find out where I lived. One A.P. jockey, Ben Walker, found my apartment, left me messages, even sent me a telegram. But my lawyer told me, “No interviews,” and I agreed, because I didn’t have any details yet, and I knew that no matter what I said, the media would end up distorting it. So I instructed my doorman to tell people I wasn’t in the building, and I kept sneaking out the back door to my friend Francis’s for some privacy.

I was distraught-and also petrified that the fact I was gay would almost certainly come out. It was hard enough for me to think about telling relatives and lifelong friends face to face, so what would it be like if they read it in the papers — and in this kind of story? But after a weekend of nonstop worry, I was relieved when the major article on Monday the 19 mentioned only my baseball problem, though it mistakenly said I resigned.

Wednesday morning, September 21, I was at La Guardia Airport on my way to catch my plane to Albany when I decided to check the papers. I picked up a New York Post. and there, in bold print across the whole back page, was this sickening headline: “Report Links Ex-Ump to Sex Scandal.”

For a few seconds I couldn’t breathe. Oh my God, I thought. My life is destroyed. And my heart hit the floor. Even though I’d sensed it coming, I still wasn’t prepared for this kind of jolt. I had put my whole adult life into baseball and in the time it took to read a single newspaper story, my career — and my reputation — were wiped out. A million things went through my mind: Who do I call first? What do I say? How do I explain this newspaper story? Will they believe it’s true? Even though it’s false, as this story unfolds, people close to me will realize I’m gay. How do I explain why I never told them?

But then, as I paid for the paper and started walking to my gate, I suddenly had the most incredible reverse reaction. I thought, Well, at least now my secret is out. How can I explain what that was like? One minute I had felt totally ruined. The next minute I felt almost relieved-like 2,000 pounds had been lifted off my shoulders. That feeling caught me by surprise. Was that my subconscious need to be my real self? Was it my guilt over living a hidden life? I didn’t know; I just knew that, for a brief moment, I felt profoundly relieved. It was like, “Now I don’t have to hide anymore. Now I’m free.”

But almost immediately I knew that reaction was a mirage. My secret wasn’t really out. The article only implied I was gay — and attached that to the worst possible connotations. It suggested I was gay (a) because I was being investigated in a sex scandal involving teenage boys; (b) because I was supposedly seen “in the company of” a number of the young boys and men involved in a teenage-sex-ring case; and (c) because I supposedly went to Saratoga Springs last year “at the request of homosexual friends who promised [me] a good time.” (This was the kind of slanted, biased reporting I’d hoped to stay clear of by not giving interviews. The logic here is that adult male homosexuals are degenerates who corrupt innocent young boys — exactly the sort of ignorant stereotyping that has forced many gays to stay in the closet. This kind of thinking is a major reason why gays in high-visibility careers — like politics, entertainment, and professional sports — know they can’t come out. If they do, it will very likely cost them their livelihood. I believe that this is why you don’t see anyone in major league baseball coming out, even today.)

Before I boarded the plane to Albany, I realized I was flying into a nightmare. I knew this scandal would force my hidden life into the spotlight- in the wrong way, at the wrong time — and that once people accepted I really was gay, most would also assume that I was involved in this sex ring. I thought, Christ, I gotta clear my name. Nothing else matters.

A couple of hours later, I met my new lawyer, E. Stewart Jones, Jr., in his office. He was a tall, dark, self-assured man who wore glasses and a no-nonsense expression. I was impressed; he was just what I had been told — understanding, probing, tough. Plus, he was also representing Bill Desadora, one of the Saratoga Springs men my friend Sam Gennaro [a pseudonym] had introduced me to the previous Halloween. Desadora was scheduled to go on trial in mid-October on sodomy charges. So, obviously, Jones was the right lawyer for me; no other defense attorney knew more about this case.

I was distressed about the Post article, so I showed it to him. After he read it, I said, “This is terrible. I did nothing wrong; why are they going after me? And how could it ever get in the newspapers? Why do the newspapers know when I didn’t even know? In any kind of an investigation, even if something gets leaked, somebody comes at you. Yet they haven’t come after me. Why? This investigation has been going on since January, yet not once did anybody from the assistant DA’s office approach me; not once did anybody question me; not once did they come to my home; not once did they call me; not once did they send me a letter. I mean nothing. They did it all behind my back. And I didn’t hear anything about it until September 15. I don’t understand that. How can they let something like this get in the newspapers without even talking to me, never mind charging me? Doesn’t that seem very unusual?”

Jones agreed that these methods were reckless and irresponsible, and he intended to present that point of view at our meeting with McNamara. Then I told him my version of the events of the weekend of December 5-7, 1987.

That night I went to see my old friend Connie Bianchi in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. I explained my predicament and she suggested that I tell her the whole story in detail. So, in effect, this is what I told her:

“My friend Sam Gennaro and his lover Paul [a pseudonym] — whom I knew from Boston — had been after me for years to come visit them in Upstate New York, where they now lived. In late October of 1987, they came to my place for a visit over Halloween. During that visit, they invited me to a party on the Upper East Side, and that’s where I met two of their acquaintances from Saratoga Springs, Larry Blodgett and Bill Desadora. Larry had a successful insurance business and Bill was a real estate broker. Sam told me they were highly respected in the community, and that’s how they behaved around me.

“The next day Sam, Paul, Desadora, and I met downtown for brunch. They said, ’You have to come visit us soon.’ They wouldn’t let up. Finally, I said I would come, but I had to pick the right time. We talked it over and agreed the weekend of December 5 was best. So that Friday I flew up and stayed at Sam and Paul’s house in Clifton Park, New York. The first night we met with Bill and Larry and went to a gay bar-which are few and far between in that area. We also hit a few straight bars. At the end of the night, we agreed to meet up the next day for lunch. Next day we woke up to a beautiful Saturday morning. Since Paul had to work, Sam said, ’Why don’t we take a drive to Saratoga Springs? You’ve never really seen it in the daytime. It’s beautiful — they have the famous racetrack and some incredible estates. Then we’ll call Bill and Larry and go out to lunch.’ And that’s exactly what we did.

“After seeing the sights, we swung over to Larry’s house, but he wasn’t home. We drove around and saw more of the area. Then we came back to Larry’s — still nobody home. It struck us as odd, because his car was there yet no one answered the door.”

“So we decided to go to Bill’s house. When we knocked there, a man with a foreign accent answered the door and said he was a friend of Bill’s and that he was staying a few days. We asked where Bill was, and the guy said he was on his way over to Larry’s house. He said, ‘I was going over there myself. Can I catch a ride with you?’ We said yes, and we all drove over.”

“When we knocked at Larry’s door this time, he answered it and let us in. We went straight into the large living room, where a football game was playing on TV. He offered me a beer and showed me around the downstairs — it was a big Victorian house with huge rooms. Then we came back to watch TV and talk. At that point there were just five adults in the room — Larry, Bill, Sam, me, and this foreign guy. About ten minutes later, a teenage boy came down the stairs. He was wearing a jacket with a backpack, and he looked maybe 14 or 15. Larry introduced me as ‘Dave the ump.’ I didn’t like that, but I didn’t mention it. The kid shook my hand and said, ‘Hi, how are you?’ and sat down on the couch with us. I didn’t know who this kid was or what he was doing there, or even if he knew we were gay. I was concerned about that, and I remember commenting to Bill, ‘He’s so young’-meaning that maybe he shouldn’t be around us.”

“Accepting the settlement meant no more legal bills, no more ostracism and having to stand alone at home plate again, acting out a farce.”

“About ten minutes later, we got up and left. Larry and Bill went to their car to go to lunch; Sam and I went to our car; the kid and the foreign guy went their own way on foot. That was the only time I ever saw either of them. I never saw the upstairs of the house and I was only in the house for a total of about 25 minutes.”

The next morning, Joe Fiore, E. Stewart Jones, Jr., and I met with Assistant D.A. McNamara in Saratoga Springs. McNamara explained that he was investigating me for having sex with a teenage boy at Larry Blodgett’s house; that the boy insisted he had engaged in sexual activity with me; and that a male witness had appeared anonymously on local TV and said that I had gone upstairs to be alone with the boy. I told McNamara they were both lying. Basically, that was it.

Over the next week to ten days, I explained the situation to people close to me. The first thing everybody asked was, “Did you resign?” I said, “I did not resign. I took a temporary leave of absence.” Then I explained about the sex scandal: “I am not involved in any teenage sex ring. I don’t know where they got their information, but I have to clear my name from that.” It was interesting that several people asked, “Do you think Pete Rose had anything to do with it because of your run-in with him?” I said, “Absolutely not. No way.”

It was amazing — not one person came right out and asked me if I was gay. Either they were too afraid to ask, or they surmised I was gay, or they didn’t read between the lines. The subject only came up once, and it wasn’t spelled out. I was talking to my godmother, who, from reading the newspaper articles, now assumed I was gay. She said, “Now I understand why you’ve had all these inner problems all these years.” And I said, “Well, I’ve been wanting to tell you for the last three or four years, but every time I tried, I got cold feet. I could not come out and tell you, because I always felt I was going to lose your love. I just could not take that chance.”

By mid-October there were still no charges against me. In the meantime, Larry Blodgett had been sentenced to up to eight years in state prison on sodomy charges (but was free on bond pending the outcome of his appeal), and Bill Desadora had admitted to thirddegree sodomy and was awaiting sentencing. Both of them had corroborated my version of what happened Saturday at Larry’s house. They confirmed that I was never part of the sex ring; I had never met the teenage boy before he was introduced to me that day, and the meeting was not prearranged; I never displayed any sexual interest in the boy; I was never out of their sight the whole time the boy was there. Sam Gennaro also confirmed my version of the story.

At the end of October, my attorney informed me that the anonymous TV witness — the foreign guy staying at Desadora’s that weekend — had just been arrested for breaking and entering, was also facing a drunk-driving charge, and had a previous criminal record. Jones also went directly to District Attorney David Wait and told him that they had already ruined my life, had absolutely nothing on me, and were banking on an unreliable witness. In effect, Jones said they had no case.

I was convinced that the district attorney’s office came after me for one reason: I was a public figure in the wrong place at the wrong time. My guess was that the foreign guy probably offered up my name to get himself out of other charges, and the D.A.’s office wanted to believe him — maybe because of the notoriety they thought they’d get if they nailed a celebrity. If I weren’t a public figure, even if they had proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that I was in the sex ring, since I was only there that one day they probably would have said, “Let’s forget it. We’re not going after him. He’s nobody.” But because I was Dave Pallone, National League umpire, they went after me big time. And no one can tell me that my name didn’t draw more national attention because of the Pete Rose thing.

As for the teenage boy, I cannot explain why he would say what he did about me. Maybe the foreign guy threatened him; maybe the kid was so active in the sex ring that he really thought he did those things with me; maybe he just wanted to brag about having been with a celebrity. I have no idea — I’m not a psychiatrist. But I do know he used me as a scapegoat.

Well, it didn’t work. On Tuesday, November 1, the D.A.’s office quietly dropped their investigation of me without ever having filed a single charge. Even today the majority of baseball fans who knew about this case in the first place still don’t know that I was never charged and that the investigation against me was dropped — and they still believe that I resigned from baseball.

In retrospect, maybe it was bad judgment for me to have gone to that house, especially given the rumors that were already floating around about me. But I would never have gone there if I had known what they were involved in. I remember a friend telling me afterward, “You never should’ve gone there to visit your gay friends.” I said, “I don’t understand. Does that mean if you have lunch with a thief, then you’re a thief, too? Suppose you go next door to visit neighbors and you walk in, and all of a sudden the door slams back and there’s the F B. I. arresting everyone for possession of cocaine. You might get arrested, too — even though you’re an innocent bystander. But forever after that, you wouldn’t be remembered as ’the innocent bystander.’ You’d be remembered as ’the guy who got busted for cocaine.’”

In other words, it really didn’t matter that I was a gay man visiting other gays. What happened to me could have happened to anybody — gay or straight. And it frequently does.

So I concentrated on one thing: clearing my name with baseball. That was why, right after my lawyer phoned on November 1 to tell me they’d dropped the investigation, I called Bart Giamatti’s office and set up a meeting for 11:30 on November 30. Over the next 29 days, other than going to the gym, I sweated it out at home. Too many people knew me, and I didn’t want to answer questions. Mostly I worried about what Giamatti would say and whether he would still be on my side.

November 30 finally arrived, and here was Giamatti starting me off with, “I know you’re not going to like what I have to say. “He was right — that meeting was the biggest disappointment of my life. How could they banish me for something I didn’t do? Why wasn’t exoneration from the D. A.’s off ice good enough for them? Where was their loyalty after I’d devoted ten years of my life to the game?”

It hurt me that Bart Giamatti was the one holding the gun to my head and saying, “We don’t want to fire you. We’d like to see you retire voluntarily.” After all the support he’d given me in the past, it felt like a betrayal. Yet because he’d touched my life in so many ways — especially by being a father figure when I needed that — I wondered if he believed this was for my own good. He’d always taken the long view with me and treated me with compassion. Maybe he figured I was better off out of baseball now, and that this whole mess might be a blessing in disguise.

I became convinced that Giamatti sympathized with me and wanted to help, but the league tied his hands. The owners were concerned about the game’s image, not Dave Pallone’s personal problems. They must have told him, “Look at all these things that happened to Pallone the last three years. Look at the notoriety he got from the Pete Rose thing. And now this sex scandal. It’s in baseball’s best interests not to rehire him.” I could understand that. Bart once told me, “No individual is bigger than baseball” — and that probably guided him here. Add the pressure of being commissioner-elect, and the fact that the owners knew I was the type of person who might take them to court, and Giamatti had no choice. I realized that although he held the gun to my head, it was the owners who pulled the trigger.

The first week of December, when my lawyer received the letter from [league counsel] Lou Haynes spelling out the reasons why baseball was terminating me, I was distraught. None of the reasons were valid:

Concern about my involvement in the Saratoga Springs scandal. I was cleared. What more did they want?

The Cincinnati bar rumor. They had investigated this rumor and found absolutely nothing.

Low 1988 ratings. The joke of jokes, even to Giamatti. Plus, how could I ever get high ratings after the Pete Rose incident?

These reasons were camouflage for the real reason: I was gay, and they didn’t want the publicity surrounding that to tarnish baseball’s macho image. In other words, they were prepared to sacrifice a proven, veteran umpire so they wouldn’t look bad.

That ate away at me. Baseball always talked about how open, fair, and inclusive it was — the all-American game that gave us Jackie Robinson. But the lesson I learned on November 30 was the biggest irony of all: Baseball was living a hidden life, too. Publicly, it pretended to be inclusive and fair, but it was close-minded and biased behind its mask. They believed I was gay, and therefore guilty of everything — and that’s why they wouldn’t hire me back. Yet they allowed Cesar Cedeno to continue playing for 13 years after being charged with manslaughter in the shooting death of a 19- year-old woman in the Dominican Republic, for which he paid only a $100 fine plus court costs. They let Lenny Randle play six more years after he was convicted of battery for shattering his manager’s cheekbone with a punch. They allowed George Steinbrenner to operate a franchise after being convicted of making illegal campaign contributions. They didn’t care when pitcher Bryn Smith was arrested for solicitation or, in 1989, when outfielder Luis Polonia was convicted for having sexual relations with a 15- year-old female minor. And how come baseball did virtually nothing more than slap the wrist of all the players who recently admitted publicly to buying, using, or selling illegal drugs?

I don’t understand how they could possibly let all those other transgressions go by the boards. How could they allow people who were guilty of breaking laws to continue their careers, but then turn around and force me out for being innocent? What was the message there — that baseball considered manslaughter, political corruption, solicitation, and sex with a female minor more acceptable than being gay?

It’s time someone pulled the mask off baseball and shined the light on its real face. Baseball doesn’t accept gays, and if what the game did to me is any measure of where it’s headed, then it’s going backward. I personally know of about a half-dozen gay major league baseball players — including some of the best-known and most accomplished players in the game — and the only problem they have is that they must lead double lives because baseball refuses to address the issue openly. And until there are drastic changes, they will stay in the closet. That’s why it’s important to know that what happened to me wasn’t about performance on the field, or ratings, or rumors about my private life. It was about discrimination. And that was the subject of discussion with my lawyers all through December, as we planned our strategy. They kept asking me, “Do you want to sue to get your job back, or do you want to swing a monetary settlement?” I wasn’t sure. I wanted to retire, yet I still wanted my World Series. I had regrets about taking the leave of absence, too. It made it look like I was guilty and then resigned, and I wanted to counter that false impression. I also figured that if I went to court and won my job back, I’d have a lot of back pay and I could work one more year and then leave on my own terms. Some of my gay friends said it would be easier for me in baseball now that everyone knew I was gay. But I wasn’t convinced everyone did know, because I hadn’t admitted it publicly. Other friends asked if I’d be able to handle the double dose of ostracism if I went back. It was a very difficult decision.

My first inclination was to fight for my job. But I’d already drained my savings to pay my lawyers. and I didn’t have a war chest or a job to replenish my funds. How was I going to pay for a long, drawn-out court case? Then my attorneys explained that even if I won, I would only be entitled to my job with back pay and benefits — no damage award. That was a big factor, because I was almost broke and I had no idea where my next dollar was coming from. Finally, I said, “Start negotiations. See what they offer.”

My lawyers computed how many years of future service I would have had up to the age of 55, and the appropriate salary, benefits, and pension numbers I would lose — and they came up with a beginning negotiation figure that was substantially more than Giamatti’s original offer. That’s why the negotiations dragged on through January and February. Meantime, I fell into a depression: “I can’t believe how bizarre my life is. What’s gonna happen to me next?” If a light bulb blew, or the mail came late, or the subway stalled. I had fits of rage. I took long walks along the East River or through Central Park, not stopping, not hearing, not really seeing, just feeling numb again. I thought, How am I going to get through the year without baseball?

On February 15, 1989, I made what I hoped was the first step toward a new future. I took a friend’s job offer and moved to Washington, D.C., to work for Events Management, Inc., a company that arranges charity functions and social events. My job was to bring in new business and coordinate logistics: hire caterers and entertainment, arrange security, even help with decorations. It was my only full-time job, other than umpiring, since high school. The first morning I wore a sports jacket and tie and I felt like someone else. The last time I dressed for work that way, I was working the 1987 Championship Series. But every day for two weeks, I got up early, put on my new “uniform,” and reported to work like millions of other people. It was awkward; I was the classic fish out of water. Yet for a while I felt good, because it looked like there really might be life after baseball.

In late February I started dreading the idea of spring: warm air, chirping birds, kids playing ball in the parks. My attorneys were still going back and forth with the league and I needed a vacation from the turmoil, so I flew to Saint Martin to swim and relax on the beach. It was working miracles — until my lawyer called and said, “They’re ready to close. This is their final offer and we think you should take it.” So I searched my heart and sifted all the input from family and friends, and I decided to accept the settlement and move on with my life. They were offering a tempting amount — much less than our starting figure, but enough for me to start a new life. It also meant no more legal bills, no more tension and worry about what baseball would say or do and how I would fight it, no more ostracism and having to stand alone at home plate again, acting out a farce. I’d had it with all the conflict. It was time for a change.

It wasn’t an easy call. Once I took the money, I’d be facing the unknown. And I would have to reconcile myself to the fact that I was going to be without baseball for the first time in 19 years, and that people would think that I was either guilty or that I sold out for the money. I did sell out for the money — because I didn’t have a bottomless pit of funds to fight baseball in court, and I desperately wanted a life again. It wasn’t the noble road, and it let baseball off the hook for screwing me out of my career. But it was my only choice.

Before people judge me, they should know two things: First, the legal agreement I signed with the league doesn’t permit me to divulge the specific figures of the settlement. Second, in a letter to me in early January 1989, Bart Giamatti wrote that “among the reasons for the League’s decision to terminate your employment were substantial allegations that you engaged in certain conduct which could be characterized as serious misconduct or acts of moral turpitude. Under our collective-bargaining agreement, the League would be entitled to terminate you without any severance pay under those circumstances.” Yet they did give me my severance pay. Why? Out of the goodness of their heart? Hardly, in fact, in my mind they gave me not only the severance pay they said I wasn’t entitled to, but also my entire next year’s salary, plus a substantial amount on top of it. What was that — a bonus for “moral turpitude”?

If I really had done something illegal or violated the morals clause of my contract, and if baseball could have nailed me to the wall for it, would they have ever offered me a dime? Why would they pay me any money — never mind the hefty sum they did pay — if they were right? What their payment said was, “We know we’re wrong and we know it would hurt us in court. But we don’t want you in baseball, so we’ll give you this not to sue us.”

“What was the message —that baseball considered manslaughter, political corruption, solicitation, and sex with a female minor more acceptable than being gay?”

Bart Giamatti died on September 1, 1989. I never had a chance to ask him if he believed me about the Saratoga Springs incident. When I called to give my condolences to his wife, she said, “Dave, I just want you to know that Bart was very upset for months about your situation.” I said, “Thank you for telling me that. You will never know how much your husband meant to me. He was a great human being. I needed to tell you that.”

That phone call was an ending for me. In a way, it might also have been Bart’s final gift of advice-because when he died, so did my anguish and regret over the loss of my career. I realized that I had the rest of my life to live, and that I owed it to myself and all the people who ever cared about me to make something good out of it.

AFTERWORD

In June 1988, during my mid-season vacation, I was· lying on a Spanish island beach thinking, “The old-time umpires could never have imagined vacationing here during the middle of the baseball season.” Then it occurred to me that, like my other trips away from baseball, this wasn’t so much a vacation as another escape. I was still hiding the real me from the world and from myself. That’s when I first considered writing a book and calling it Behind the Mask. But I didn’t have the time to sit down and do it. Then a nightmare called the Saratoga sex scandal wrecked my career and almost my life, and I had the time to tell my story.

I had several reasons for doing it:

- My side of the controversies plaguing my baseball career has never been told. Whenever I tried to explain myself publicly, my words and thoughts were taken out of context. After the Saratoga sex scandal, reporters were more interested in distorting the truth than uncovering it. So this book sets the record straight and allows people to judge me fairly.

- I believe it’s time for gay people in the public eye to come forward and say, “This is who and what I am.” I want this book to say, “If you’re gay, think about removing your mask. Because unless more of us do that, the backroom politics of prejudice will continue to destroy productive careers and lives.” I realize that some people will think, “That’s easy for you to say. You have nothing to lose.” But that’s not true; I have a lot to lose. For one thing, I have never come out publicly and admitted I was gay, so I am risking many important friendships by revealing myself here. Second, I am still searching for my new career. While I hope this book helps both gay and straight people to rethink their values, I also know that it will shock some potential employers and cost me opportunities.

- Our society expects its male sports figures to be “macho,” and many heterosexuals still cling to the myth that all gay men are effeminate “Nellies” working as hairdressers, fashion designers, dancers, or artists. In this book I wanted to dispel those myths and make it clear that gays are just as macho as straights, no matter what career they’re in.

- As of this date, not one gay major league ballplayer has come out of the closet — and it’s obvious why not. I hope this book conveys to heterosexuals the terrible scrutiny gays in public life are under, and how vulnerable we are to prejudice in society.

- I hope that gays who read this book will be encouraged to be themselves, tell their secret to the people they love, and be proud of their humanity. The book should say to them, “Have courage and pride and be true to yourself. Let people close to you help you. Let the world see you for the person you really are.”

One final note: There has been a lot of tragedy in my life, which I talked about openly in the book. But I want to be clear that I am not asking for sympathy. I am not asking anyone to shed a tear for me. What I am asking of people who read this book is what I’ve asked of everyone I’ve ever known: Accept me for who I am — a decent human being, just like you.