Shortly before dawn on July 18, 1981, Richard Adan, a twenty-two-year-old actor, playwright, and part-time waiter, stepped outside his father-in-law’s restaurant on New York’s Lower East Side with Jack Henry Abbott, a recently paroled ex-con who was living in a nearby halfway house.

Penthouse Interview: Jack Henry Abbot

Jack Henry Abbott had wanted to use the restaurant’s rest room, which Adan said was reserved for restaurant employees. Mr. Adan was showing him a spot he could use outside. Abbott maintained that Adan had aggressively taunted and provoked him into a fight in the street. In any case, Adan was lying dead on the sidewalk minutes after going out the door. He had been fatally injured by a single knife-thrust to the heart.

Later that morning, as police began a nationwide search for the fugitive Abbott, the Sunday newspapers carried the reviews of Abbott’s just published book, In the Belly of the Beast. “Awesome, brilliant, perversely ingenious,” asserted the New York Times Book Review, “its impact is indelible, and as an articulation of penal nightmare it is completely compelling.” The Washington Post, Time magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and scores of others concurred.

The story of Jack Abbott did not, however, begin with the morning of Richard Adan’s death, or even with Abbott’s sudden literary celebrity. Indeed, as the New York Times editorialized at the conclusion of Abbott’s trial, the killing of Adan as well as Jack Abbott’s blasted hopes epitomized the “awful failure of criminal justice.”

A self-described “state-raised convict,” Abbott had spent virtually all his adult life behind bars. Born in 1944 in Michigan, he was the second oldest of seven children. With his father serving overseas in World War II and his mother unable to support the children on her meager earnings as a maid, all but two of the children were given up for adoption. Abbott and his sister were placed in what, for Jack, was to become a long succession of foster homes. He constantly ran away from the homes, and was finally deemed incorrigible and committed as a juvenile delinquent to the Utah State Industrial School for Boys at age twelve. In 1963, after being arrested for passing bad checks, he was sentenced to a maximum of five years’ imprisonment at the Utah State Penitentiary in Draper. In 1966, while serving that term, he was given a concurrent sentence of three to twenty years for the fatal knifing of a fellow inmate, a trustee who Abbott claims had “snitched” as well as threatened him with gang rape.

On March 13, 1971, Abbott escaped from the Utah prison and within a week had robbed a bank in Denver, Colo. Captured the next month, he was convicted of armed robbery and given a nineteen-year federal sentence. With a self-admitted record of more disciplinary infractions than any convict in the federal prison system — although he argues that many were “frame-ups” — Abbott spent the 1970s in a half-dozen penitentiaries, including Atlanta and Leavenworth, before being transferred in 1979 to Marion, the “hardest joint” in the federal system.

While in prison, Abbott was an enthusiastic reader and regularly received books through P.E.N., the writers’ prisoner’s-aid organization. In 1977, after a correspondence with Jerzy Kosinski, the Polish-born novelist, Abbott noticed in a newspaper story that Norman Mailer was at work on a book based on the life of Gary Gilmore, the convicted murderer. Writing Mailer, Abbott offered to help him understand the true nature of violence and brutality in American prisons. Abbott’s letters, written by hand, often ran to twenty pages or more. Philosophical, ruminative, angry, and above all terrifying in their descriptions of maximum-security confinement, Abbott’s writing outlined the code of courage and wit needed to survive not as a “punk prisoner” but as a man. By June 1980 the New York Review of Books published a selection of these letters, and shortly thereafter Random House, the distinguished New York publisher, signed Abbott to edit and shape his writings into a book.

The consensus through out the literary community was that Jack Abbott, the emerging writer, was nothing less than a phenomenon.

Meanwhile, Abbott, still serving his nineteen-year bank-robbery sentence, was seeking parole. Mailer, editors at Random House, and the New York Review of Books all wrote to the parole board officials, testifying to Abbott’s extraordinary abilities. Thirty-six years old at this point, he had been in custody for all but nine months of the previous twenty-two years. Among fellow inmates he had acquired the reputation of a reformer; among officials, as a troublemaker. The lead plaintiff in a class-action suit in which eighty-seven inmates sought reform of prison regulations concerning mail — a suit supported by the National Prison Project of the American Civil Liberties Union — Abbott had spent long stretches in solitary confinement, which, by his own account, were often accompanied by beatings from prison guards. In Marion, which was gripped by a prisoners’ work stoppage in the spring of 1980, the brutality allegedly worsened. On May 5, 1980, Abbott was notified by the U.S. Parole Commission that his June 20 parole date was being put off because he had “engaged in and encouraged a group demonstration.” Abbott was given a new parole date, August 1981, again conditional on good behavior.

“Jack took the delay very badly,” said a Midwestern attorney who was in touch with him then. “He wanted out of Marion; he had become deathly afraid of ending up in a cemetery plot there. Jack knew the system as well as anyone. He had seen inmates killed just because others didn’t want them to go free and he thought maybe the administration was setting him up. He was frightened.”

It was at this point, Abbott having been “broken,” that he began cooperating with prison authorities, providing the names of inmate leaders in the Marion work strikes. Though he insists that the information provided was already known to officials, the Marion Prisoners’ Rights Project was barred from the prison ten days later. Within three weeks, on January 16, 1981, Abbott himself was transferred out of Marion and turned over to Utah State Prison, allegedly for his own safety. Three months later the Utah Board of Pardons ruled that Abbott’s state sentence could be “terminated.” His book was about to be published, and although psychological testing had shown him to be “angry and hostile,” “his hopes were up and he had a lot of plans.” Indeed, for Thomas R. Harrisson, chairman of the parole board, people “who knew better than I” had attested in letters to his “sensitivity, talent, goals, and accomplishments.” Given Abbott’s testimony at Marion, it was altogether possible that a deal had been struck. On June 5, inmate Jack Abbott was turned back over to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, which placed him in a federally supported half-way house on the Bowery in New York City, his full parole to become effective August 25.

The rest is current history. After a highly charged three-week trial in which the defense claimed “extreme emotional disturbance,” Jack Henry Abbott was convicted of first-degree manslaughter in the death of Richard Adan and returned to prison. For all of New York’s dailies, as well as for Time and Newsweek, the verdict and the issues of the case stimulated an editorial outpouring. Prisoner rehabilitation, recidivism, literary radical chic, and the woefully inadequate procedures for “readjusting” long-term convicts to the street — all were debated. Abbott, his book, and the killing of Richard Adan, it seemed, had touched the most sensitive, fibrillated of nerves.

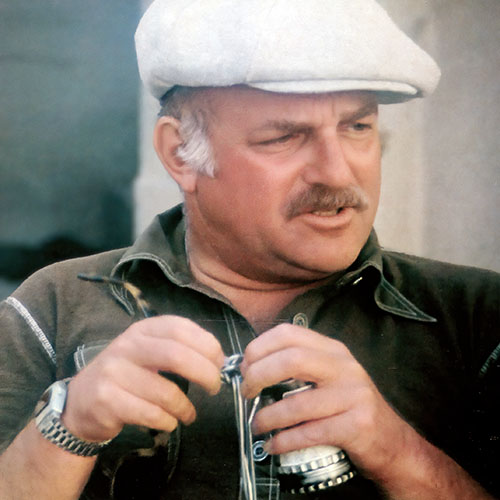

To plumb these issues, as well as the personality of Jack Abbott himself, Penthouse assigned writer Peter Manso to travel to the Springfield, Mo., U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners and speak with Abbott. Manso reports:

The notion that Jack Abbott had mastered something in himself by learning to write as well as he does, learning in the worst of circumstances, wasn’t untenable. That he later stabbed Richard Adan was fact. Still, I’d first met Abbott two weeks before the killing, had dinner with him after walking the beach in Provincetown with him, and there was no sign of violence. Thus, when it all came down, one had to ask why. And beyond that, eclipsing the tragedy all around, there was the broader issue of responsibility, not to say the nightmare paradox of Abbott’s own head. If a man could so perfect his vision, so sharpen his sensibility, then how (and here one must insist) could he have so misread Adan? What for others might have been little more than a rebuff? It was a problem not for psychologists, no, nor even the keenest of sleuths. One had entered the land of convict dread.

At Springfield, Abbott had been limited to one-hour-per-month ‘media time.’ This was extended to a single six-hour session. The setup: a conference room with Abbott locked into the equivalent of a telephone booth, the interview conducted through the finest of steel-mesh gratings. A guard posted outside in the corridor (spic-and-span, for sure), bombardment-like fluorescent lighting, and, finally, a nonstop cacophony of announcements from the prison’s P.A. system, all added to the institutional scenario.

“Two packs of cigarettes later, the time was up. As the complement of four guards arrived to return Abbott to his cell, he merely nodded his good-bye, once again dealing with officialdom.”

On July 18, you were in New York City, awaiting parole after spending nineteen years of your adult life in jail. You had just published a book that the New York Times called “brilliant.” One of America’s most famous authors was acting as your sponsor. Dante writes about the vita nuova — “the new life” — a form of deliverance. You had everything all laid out in front of you. Why did you fuck up?

Abbott: Because I didn’t get delivered to no Paradisio — they didn’t put me in the right place. They delivered me right back to prison.

Start from the beginning. What happened after you were released from jail?

Abbott: Norman Mailer met me at the airport at about 1 :00 A.M. My plane was late. Then I took a cab to the halfway house. When I got there everything was closed down. The doorman showed me to my room and I laid down and tried to sleep, but I couldn’t. I had jet lag. So I sat there until it started getting to be daylight, then I got up and looked out the window. All I could smell was garbage. There was like a real fine dust of garbage everywhere. I saw all these people out on the sidewalk: old winos stumbling around, people who looked like they were hallucinating, people just laying out in the gutter. I wondered, what the hell was this? I went downstairs to get a cup of coffee, and as soon as I got outside all these people started running up to me begging for money. They were just rolling around on the sidewalks. As far as I could see in all directions it was like that. There wasn’t that much traffic at that hour; newspapers were blowing across the streets. All the people looked like they were in a state of death. Dead but upright.

Did you know where you were in New York?

Abbott: I knew it was the Lower East Side, that’s all. I came to find out that there was a men’s shelter across the street with thousands of crazy patients turned loose. You’ve heard of the Slasher? They arrested him about half a block from the halfway house. It’s the most violent part of the whole city. The most stabbings and the most killings take place down there. I saw a guy stabbed right in front of me. His blood splashed onto me. Another time, I was talking to someone on the street and a car was fire-bombed right behind us. You know how they do that? They put gasoline in the car and they ignite it and it just goes up in a big kaboom!

Were you conscious of the possibility that it was a mistake for you to be in that neighborhood?

Abbott: Well, I was very conscious of the possibility that I would get in trouble, that somebody would jump me. That there would be a little bit of blood somewhere and that I would probably be sent back to prison.

Did you tell this to anyone?

Abbott: I went to see my parole man and I told him, “Look, you’ve got to get me out of this halfway house.” But I was told that it was the only halfway house in New York that would take me. The officer said it would take about two or three weeks of paperwork to get transferred — that they’d have to check this and check that and by the time they could make arrangements, my time in the halfway house would be up. So I had to just set it out, that’s what it boiled down to.

You see, people always want to try and find something dramatic or tragic in Adan’s stabbing. But it was nothing like that. It was just something that happened.

“Just something that happened”? You were carrying a knife, you stabbed him. How can you say it wasn’t tragic?

Abbott: Yeah, well, if it was, it didn’t have anything to do with me. It was in my psychology.

But it wouldn’t have happened if you hadn’t been carrying a knife.

Abbott: Yeah, the thing that I was at fault with was carrying the knife, sure. But the Lower East Side was a terrible place. To me it was just like being in a war zone. I felt I had to carry a knife with me whenever I went out anywhere in the neighborhood, at least when I was alone.

Did you tell people you were carrying a knife?

Abbott: Yes. Everyone told me just to avoid being in that neighborhood as much as possible.

No one told you the knife might get you into a jam?

Abbott: I don’t think that they perceived it as a jam. I mean, it isn’t a jam if somebody just leaps up off the sidewalk and attacks you as you’re passing and cuts you a few times and tries to rob or stab you. That isn’t just a jam. It’s a matter of having to protect yourself.

Are you talking about pride, honor?

Abbott: I’m talking about physical health, damn it.

You could have been set upon by a dozen guys, but if there was any trouble, it would be your ass, not theirs, in the eyes of the law. You were awaiting full parole, you weren’t supposed to be carrying a knife. Did you think of that?

Abbott: Yeah. But when I was released I wasn’t free to move and live where I wanted to. I was stuck there, in that one halfway house that was in the most bombed-out area in New York. The most violent area in the city.

But you had to be aware of your position. You’re released from a life-time in prison. The lampshades have turned to gold, you’ve got a new life …

Abbott: People keep wanting to see this as if it was happening on a movie screen or something. It isn’t a movie! That’s not the way you should look at it. Forget that cinematic picture of me getting out and being some kind of celebrity. That’s not the way I was seeing things.

Then let’s begin with the premise that you’ve had a pretty bad life. And you produce this extraordinary book, and through a chain of events you’re released from prison. You have an opportunity to start all over again. This doesn’t accurately describe. The situation?

Abbott: No, I never saw it in those terms, damn it. That’s bourgeois bullshit.

Why? You couldn’t believe it was happening?

Abbott: I served nineteen years in adult prison. Why don’t people understand that I was in there to serve time? Then I got out of prison, and it wasn’t because of the book. My book had nothing to do with me getting out, really. I served my time and I got out, you know? Now, am I supposed to feel like I’ve been redeemed or something? I was relieved to be out. I was relieved to be out of prison, that’s all. But the trumpets never played. I didn’t get any spiritual … I didn’t experience any Donald Duck emotion or whatever the fuck they call it. The thing is, I just got out of prison, plain and simple. I didn’t have any whole new life. I had my whole life, and the present was just a continuation of it. I guess a lot of white guys say that when they get out of prison, they go through a lot of psychological changes. They get maudlin and sentimental about being home and all the rest of it. But that didn’t occur to me. I’m almost forty years old, see? Those things don’t occur to me.

What was your response to your instant celebrity?

Abbott: I didn’t see it as any celebrity. I think a lot of it was concealed from me. People probably didn’t want me to get conceited. I knew that my book was being reviewed by the top, the New York Times, Time magazine. But I have also read people reviewed in the Times who were never heard from again. Time magazine reviews books every week. I knew I could write; there was no question about that. But I didn’t care about anyone’s response to it. The main thing is, I don’t have any respect for this society. I don’t like this society. I don’t like this country. I was going to leave it as soon as I could. As a matter of fact, I had been talking to editors at The New York Review of Books about it, and Bob Silvers, the head guy there, was trying to arrange for me to go abroad on some assignments for them so that I could travel and find someplace to live.

Why do you hate this country so?

Abbott: I hate this country because of what has happened to me here. They have pushed me to the limit since I was a kid. Whenever I’ve been out of prison I’ve felt so fucking bitter I couldn’t even see straight. Do you know what that’s like? Everything tastes like shit and all your memories — even the good ones — become all bad.

What happened the night of Adan’s stabbing?

Abbott: It was about 3:00 A.M. I was with two girls, and they wanted to get something to eat in my neighborhood. I should have known better: than to stay in that neighborhood. We’re in this Bini-Bon café and Adan comes over to the table and gives us menus. We start to order and he puts his hand on my shoulder and looks at Susie and says, “I don’t take orders. That’s the guy who takes orders,” motioning to another waiter. So we’re eating and later on he looks at me and says, “What are you looking at?” I turn away from him, try to ignore him. And then I hear him again: “What are you looking at?” I don’t look at him. He starts to step over. So I get up and walk over to him and I ask him why he’s saying this to me. “Have I done something to you?” I ask. “No, no,” he says. “Then what did you say that for?” I ask. “Say what?” he says. “What’s wrong with you?” “Nothing’s wrong with me,” I reply. “What’s wrong with you?” Soon I got tired of it and I turn and walk back to my table. I’m thinking, well, it’s nothing. I’d have walked out of the cafe if I’d been alone the first time he said it..

But as I’m walking back to my table, Adan’s talking loud and people in the room were listening and watching. So I turn back around to him. You see, I keep thinking that he’s going to come over to the table and upset us. So I say, “Look, if you really got a problem, let’s talk about it someplace besides in the middle of this floor.” Meanwhile there’s another waiter walking by. Adan says, “Do you want to go outside?” That’s when I looked at him and started thinking, He’s really coming on. He’s really too aggressive. I figure the other waiter knows him; he can talk to him, calm him down, so I say to him, “Look, we’ve got a problem here. Is there anywhere we can go to discuss this?” I’m thinking that if I talk to him nice, then he’ll talk to Adan and cool it off. I want him to see that I don’t want any trouble, that I’m not acting aggressive. He says, “I don’t know.” “What about a cloakroom?” I ask. “We just throw our things on the floor in a pile when we come to work,” he says. I’m standing there trying to figure out what to do. I see a door to the kitchen. I say, “What about in there?” He looks at me and says that customers aren’t allowed to use the rest room.

All this time, Adan is standing there mimicking me, taunting me. So now Adan says something about how the customers aren’t sanitary. I say, “Look, I don’t want to use the rest room. That isn’t the point.” Adan then turns around and reaches behind the counter, like to put something in his pocket, and then turns around and hits me in the chest. He jarred me, and I took a step back and told him, “Okay, then, let’s go outside.” I didn’t think he’d do anything now. He’s acting like he’s got a knife in his pocket and I’m taking it that he’s bluffing. I’ve seen a lot of people do that, so I’m not paying much attention to it. So I go out the door. I pause to say something to him, and he says, “Go over there” and points to the corner. Now, I’m trying to talk to this guy, and I turn back to say something to him, but before I could turn all the way around he says, “Go around the corner” and he’s walking right behind me. I’m thinking, Well, he’s playing a game like I see kids playing all over New York. They talk like they’re in the movies. They talk real loud and say that they’re going to hurt somebody. Adan was, like, acting. He was trying to scare me. He was putting on.

Now, I know that I’m not going to find anybody who will say that Adan was the type of guy to do something like that, but that’s what he did. So I was thinking, Well, I’m just going to let him lead me wherever he wants to and then when he’s tired of playing his game, I’m going to ask him what’s wrong with him. So I walk around the corner and he’s right at my heels with his hand over his pocket, pretending he’s got a knife in there.

When I stopped walking, that’s when I started getting worried. I didn’t know where I was. It was dark and there were broken bottles and garbage all over the place. When I turned around, I could see that he was about ten feet away from me. I thought he was going to dive into me, take a shot at me with that knife and just jump back out. That’s what he looked like he was going to do, and I’ve seen people do just that. So I hollered at him and told him not to come any closer. I pulled out my knife. I held it up so he could see it and I started to come around him. I’m thinking that this guy is fucking nuts. And I was just trying to get up out of there. But I’m going to defend myself if it comes to it. I’m going to stab him. But at the same time, I’m going to try to get around it. I shouted again, “Now stay where you are,” and I’d just started to say, “Don’t come any closer” when he just came right at me.

There’s no question in your mind that he came at you?

Abbott: No question whatsoever. He came at me. He charged me. He dove at me.

Why? It doesn’t make sense.

Abbott: I don’t know why, I don’t know. Like I’m telling you, the only thing that anybody knows about him is that he was a waiter at the Bini-Bon and that he was going to acting school and that he wrote a play. Have you ever seen Adan’s play?

No.

Abbott: No one has. I wonder why not. I mean, is it written? Supposedly, he had completed a play. But I know that a producer went down to New York and tried to get it and was told it wasn’t done. Anyway, I know everyone says that a guy like Adan doesn’t do that kind of thing. I can’t argue with that. I don’t know why he did what he did, but I also don’t know why people do a lot of things, and you don’t question things like that at the moment they’re happening.

You know, I’ve never spent more time thinking about anything in my life than Adan. When I was a fugitive, I was thinking that if I got caught, all I’d have to do is get a good lawyer and show him exactly what happened and even though I’d probably be sent back to prison, there wouldn’t be any question that I did what I had to do. If I had known what the press was doing, I would have probably gone looking for some information on this guy.

For what reason?

Abbott: It might have given me the information to answer your question, why Richard Adan would do something like that. Right after it happened, I put it out of my mind because, to me, he was nothing but another one of those guys on the Lower East Side, probably a junkie, some kind of nut.

And I just couldn’t believe when I started hearing people questioning what had happened. I couldn’t believe it. I started thinking about it over and over. I never quit thinking about it.

But you see, now we have to take great care in talking about Adan because he is dead. Because of this and because of my past and because the press has come down so hard on me, nobody wants the responsibility of saying that perhaps Adan … might have … uh … asked for it.

How? By his inept movements?

Abbott: I didn’t say he made any inept movements. I told you he made a movement at me.

Inept in the sense that things would have been totally different if he ‘d just said, “Okay, man, enough,” and walked away.

Abbott: Yeah. You see, if anybody talks about this and attributes what happened in any way to Adan’s inept movements, then they feel that it is somehow justifying his death. So they won’t say that. It’s such a whole bunch of shit. It’s getting to the point where I’m just getting tired of even thinking about it.

How do you respond to this quote from an editorial in the New York Times: “Nobody familiar with American corrections can honestly say that the experience of Jack Henry Abbott is unusual. The conditions that created his rage and the official cynicism that may have helped his release are routine in penal institutions all over America. That’s why, finally, the case of Jack Henry Abbott symbolizes an awful failure of criminal justice. ‘When Americans can get angry because of the violence done to my life and the countless lives of men like me,’ Jack Abbott wrote, ‘then there will be an end to violence. But not before.’ It is certainly time for him to go back to prison. Perhaps it is time for the rest of us to get angry too.”

Abbott: I can’t answer to the New York Times. Those people are flat liars. The things they say don’t affect me. That’s your world. I don’t like this society; I don’t like the people in this society and the people who write those things are little, little chicken-shits. They have middle-class lives and they’ve never had to be questioned about anything. They’re the ones who run things. It’s easy for them to take positions. They don’t like my book because I’m a communist.

Do they have the right to be angry that Richard Adan was killed?

Abbott: They don’t got the right for a fucking thing.

Why not? Because by your lights they haven’t paid their dues?

Abbott: They haven’t paid their dues, exactly.

Simple as that?

Abbott: Simple as that. They don’t got the right to tell me all this shit when they did all that they did to me. And the thing that is outrageous about this is that there’s a stubborn refusal to understand what really happened. I served nineteen years in prison, I get out, and they threw me in the Lower East Side. I got into a fight with a waiter and he gets killed, and now they try to cast this Adan into an angelic mold. They’re putting a whole different perspective on it. They’re refusing to understand it because of the book. I’m telling you, it’s because of my book.

Have you heard any of them talk bad about my communism? Have you heard any of them say that Abbott would like to see the U.S. government overthrown? Or that Abbott would like to see their lives taken away from them? Have you heard them talking about any of that in the news? No. They talk instead about how angelic Adan was. They throw him all out of kilter; they throw the whole situation out of kilter.

Did you know that this country, the United States, uses books to start off their propaganda campaigns? You know what happened in Argentina?

The Falklands crisis?

Abbott: Yes. You know they opened up their propaganda campaign against Argentina with that book by Jacobo Timerman? And with all the propaganda, if someone wanted to have a book that they could hold up against this country, they’d certainly hold up In the Belly of the Beast. My book is now published in twelve or thirteen foreign countries. And it’s probably safe to say that if any of those countries wanted to say anything bad about the U.S., they’d refer people to my book.

You don’t think you’re inflating its importance?

Abbott: It’s a result of all the publicity that they’ve poured on the book, all the slander that they have done to me. Every major magazine has written on me, every one of them. The thing that I’m saying is that they didn’t write about me because Norman Mailer helped an inmate get out of prison who killed a waiter on the Lower East Side. That wasn’t why they made all that noise. That wasn’t why my book was sold in the first place. A first author doesn’t sell a book like that. You asked me earlier if I was aware of the significance of the book — of my being given a big break because of the press attention. And I told you that I didn’t, because I didn’t know the importance of Time magazine and the New York Review of Books. Mailer had told me that it would probably sell maybe 40,000 paperbacks and that would be it.

But then I knew, in spite of what anybody said, that that book was going to cause me some serious problems. I knew that it wasn’t going to just get published and be forgotten. I knew that it was going to sell more than what Mailer told me. I never said anything to him, because he’s the expert.

When did you realize what impact the book would have?

Abbott: I didn’t really notice the impact of it until I saw the galleys, until I saw it in print. Then it had an identity of its own. I was removed from it then. I could look at it like it was a book that somebody else had written. And then I knew that it was going to cause a stink, because I knew about prison literature. I knew that this was something that had never been written before. I told my sister at the time, “This book’s going to make me the most hated man in this country.”

Again, you’re not being a little grandiose?

Abbott: I think it probably has made me the most hated man in the country. I get letters from people telling me they don’t understand how I can stand up under all the hatred directed at me. I’ve never read anything that’s even neutral on the subject of me. Everything is against me.

Untrue. Reviews, editorials like in the Times—

Abbott: It’s all a complete failure to understand. The most, the worst that anybody could know about me is that I got out of prison, and then got into an argument with a waiter. But we both agreed to go outside. We went outside, and in the ensuing struggle, I killed him. Now that is not so … I shouldn’t be compared with the Boston Strangler or somebody like that. People might not agree with it, but it’s not such an awful, outrageous, inhuman act that requires that all this hatred be directed at me and that all these things in the press be said about me.

You wrote about “prison paranoia.” Isn’t it just possible that this is what’s operating here?

Abbott: I don’t like to use the word paranoid no more because most people don’t understand it. But I have become apprehensive, sure. Ever since Adan, I have had trouble writing to anyone without being angry, without having that tone. And it bothers me. I sit down to write a civil sentence and I can’t do it.

“I hate this country because of what has happened to me here… Whenever I’ve been out of prison, I’ve felt so fucking bitter I couldn’t even see straight.”

Why not?

Abbott: I’m trying to get ahold of this thing, but I don’t know what it is. I’m on the defensive, I keep thinking there’s something that people are thinking, something real crazy about that Adan thing. But, all I know is what he did, what he said; his character, or what may have been going on in the back of his mind, that I can only infer.

From your tone now, though, there doesn’t seem to be any guilt or sorrow for having stabbed him.

Abbott: Guilt? No. Only remorse. You can have remorse for something like that without having guilt.

Explain the distinction.

Abbott: Having conscience, what I call remorse, for killing somebody doesn’t have to spring from guilt. The thing that’s so bad about it, whenever you think about it, is that it has a lot to do with mortality, with someone’s not getting a second chance. It has to do with the lifetime represented in anybody.

You’re talking about the finality of killing, its absolute, irreversible dimension?

Abbott: That’s what I’m saying, that’s the whole thing. Right there is grounds for grief. It doesn’t matter who it is. I don’t care if it’s Hitler. You know how Christians beam when they think that a sinner has been “born again”? Well, it’s the same thing. I’m a communist, you know that, and given my faith in rehabilitation, there’s no point in having to kill somebody.

For the record, though, Adan was not the first man you’d killed.

Abbott: No. There was a guy at Draper, another inmate. I had just gotten out of the hole. I’d had some real serious problems in that prison; I’d been there three years and had a bad thing with the inmates, most of whom were from my reform school. They had betrayed me whenever they got the chance. They also agitated people to come and crack on me, you know, to come and hit on me, and they sent this particular guy over to provoke me. He had informed on an escape attempt I’d been involved in — he was a trustee, had spotted me trying to lob the casing for a pipe bomb over into the exercise yard, me and another guy — and when I found out that he’d snitched, I let him know and he said, “So what are you going to do about it?” Two or three weeks passed. He kept egging me on and I wasn’t doing anything about it because I knew he was buddy-buddy with the guards. Then he started saying that he was going to fuck me. Some people were laughing about it and an old con I knew told me I’d better do something about this guy. You can’t let something like that pass. In prison if you have trouble with someone, unless the guy’s a real good friend, it almost always ends in violence. There’s no other way out, cause you got to live there, you know, in those two square acres, maybe for ten years.

So anyway, I knew the night this guy was planning to rape me. The guy I’d been getting advice from had a knife hidden in a hollowed-out chair leg. I’m walking down the hallway when the guy who’d been threatening me, him and his friend, follow me, walk up beside me, one on each side. They got me packed in between them. And so I pulled out the knife and I jerked free from them. When I did that, the guy saw the knife, put his hand in his pocket, and his friend swings a two-by-four and knocks me down. I’m on my knees. I have the knife in my hand and I have a hold of the guy’s hand inside his pocket. They don’t know what to do with me. So I swing the knife and I hit him in the side as he’s turning around to get away and the knife went around and hung up in his spine. Then I stabbed him again. I kept stabbing him and then he brought his arms up to block his chest and his right arm fell away, severed right up near the shoulder. He slumped down on the floor but his friend keeps knocking me down and I just kept bouncing back up and swinging the knife. I was really hurting; he’d cracked some ribs and was still swinging the two-by-four, so I stepped into him and stabbed him in the neck.

Now, you’ve got to know that when all this was happening, inmates started hollering and by the time it was over, there must have been 200 or 300 of them packed wall-to-wall watching us and agitating the whole thing. They’re yelling, “Get him, Abbott! Get him!” They didn’t like these two guys, because they knew they were snitches. Finally, though, a guard told me to throw down the knife. They took me into a strip cell, maybe half a dozen guards, and beat me. The guy who’d snitched on me died ten days later in the hospital.

But what was your feeling afterwards? This was the first time you’d killed someone. Was there remorse?

Abbott: I felt a change come over me, but I didn’t really know what it was. I had a lot of very bad dreams about it, probably from the shock of it. But no, there was no remorse.

Did it change your relations with the other inmates?

Abbott: Well, once you’ve killed somebody, especially with a knife or a club — in a violent, close-up, physical way — it doesn’t matter that people know that you didn’t have a choice. There’s still that something in them, they’re afraid of you. Or I shouldn’t say afraid — they’re uncertain of you. They don’t want to be alone with you. They’re not sure what your reaction might be if there’s an argument and you happen to get mad.

Killing confers status, though, doesn’t it?

Abbott: They call it status, but I never took advantage of it. I couldn’t have anyway, because they put me in the hole. I never got out of the hole in Draper until I escaped.

How could you have taken advantage of it, though, if you’d wanted to?

Abbott: You’d have someone run errands for you. You could have just about anything you want. I got to say, though, that the only people I’ve ever abused in prison are guys that push other guys around. And I make myself available to it, intentionally.

Coming back to your reputation on the outside, though. What kind of correspondence have you received since being reimprisoned?

Abbott: Everybody supports me. I’ve lucked out. I’ve had one bad letter.

Out of how many?

Abbott: Probably about five or six hundred.

Who writes to you?

Abbott: Mostly women. They want to tell me how they were struck by my book and that they sympathize with me and all that.

At the same time suggesting that you deserve some special break because you’re talented?

Abbott: Well, I never got a break.

Some people have the idea that talent redeems.

Abbott: Redeems what? What was wrong with me before? When I was eighteen years old I cashed a bum check. I went to prison for that. Now is that so awful? That was twenty years ago. I’m not better than anybody else. I’m not real worse than anybody else either. I think a better way to look at it is that I should be rescued from this place, not redeemed.

We’ll come to the subject of prison conditions and how you’ve been treated in a moment. Here’s a quote from your book: “There are some men who cannot be rehabilitated, and these men belong in prison.” Do you believe this, that there are individuals who should indefinitely be kept in prison?

Abbott: In this society, yes. In that passage, though, I was talking about the type of person who considers prison his way of life.

How about the clinical classifications of “psychopath,” “psychotic,” “sociopath”?

Abbott: No. I believe more in what you would call a social class. The important difference in a man is the way he goes about earning his living and what his social origins are.

These things solely determine his behavior?

Abbott: Yes.

“I knew my book would cause a stink… I told my sister, “this book’s going to make me the most hated man in the country.”

Do you go along with the definition of a sociopath as someone who fails to distinguish between right and wrong, who has no conscience?

Abbott: That’s one of the classifications that they use to justify the death penalty. But you can’t talk about conscience without talking about class. If somebody from the working class has to rob a store and has to knock somebody down who resists …

It’s justifiable for a poor man to kill someone in the course of a robbery?

Abott: Somebody who is just trying to exist? Yes, conscience depends on if you’ve done something wrong, it’s not what anybody’s feelings about it are. What’s right is right. Now, if because of his social situation a guy ends up in a supermarket with a gun at the manager’s belly telling him to give him the money, he’s not going to get pangs of conscience because he’s forced to do it. You do what’s necessary, what you’re forced to do. And if you’re forced to do something, it’s very regrettable.

Where does repentence enter into it, though?

Abbott: I’ve seen convicts do that jail-house repentence bit all my life — that born-again bullshit. I can’t bring myself to do something like that. It would force me to admit to things that aren’t true.

Like what?

Abbott: Like that what happened was a question of my not being rehabilitated in prison. The simple, blunt thing is that they did this to me because of the book I wrote and …

But damn it, you did kill Adan-

Abbott: There we go again. It’s Adan, Adan, Adan. Listen. If you think that someone is coming at you and your life is at stake — no matter what was in your attacker’s mind — and you kill him instead, even inadvertently, then what’s the problem? What’s the problem, tell me? Don’t people have any understanding?

The problem is that not everyone would have done the same thing if put in your place that night. That’s the problem.

Abbott: These are the values that I grew up with as a man. If I was a kid in this society today, they’d be telling me that I’m supposed to behave in a certain manner, and that on certain points I’m not supposed to back down. We grow up knowing this. I don’t know if everybody would do what I did. It all depends on what you were taught to do, on what you were taught was right.

“Right”?

Abbott: To defend yourself, yeah. It isn’t a question of not backing down; it’s if you’re right. If you are right. If you’re wrong, you’re supposed to apologize. You’re not ever supposed to take a wrong position. I read a copy of the Village Voice recently with an article about me by Bruce Franklin, who was recently purged from the Revolutionary Communist party. He said some things that I thought were perceptive about the difference between me and the ordinary white prisoner who gets out of prison. He talked about me in relation to Malcolm Brady and that fool Bunker, who blame themselves for the conditions of prisons and blame themselves for going to prison in the first place. I can’t do that. Not because I don’t want to. I’m aware of the vanity of my position, the self-righteous attitude. I’m aware of that, but I can’t let it stand in my way, because the people who are leveling those kind of charges at me are people who have an outlook on life that I don’t agree with.

I believe that you are a product of your environment. And I think that whenever you’re being criticized for doing something that the environment taught you to do, you must point out that it was not what you wished to do or what you wanted to do; you did what you had to do.

What about the idea of personal responsibility?

Abbott: You’re not responsible for your conditions, not unless you can control them. I have never been in a democratic society. If I had had all the freedoms of an ordinary citizen, then it would have been different. But I don’t have those freedoms. I don’t have any freedoms to do anything about my condition.

What if they opened the door right now and you were free?

Abbott: I’d ask somebody for enough money for a ticket out of this country.

To where, though?

Abbott: To Cuba.

Why Cuba?

Abbott: Because it’s a socialist country. From there I could travel behind the Iron Curtain. I could have employment; there would be something for me to do. I would like to go to Nicaragua. I would like to learn Spanish. I’d get involved in the economics of that country; I’d get involved in land reform down there. Those people down there, they don’t have shoes. They have to import shoes. Ordinary things that are industrially produced here are still handcrafted down there. I’d like to go and try to help. In this country, though, if you’re helping people who are down — poor people — then you’re trying to bring them up through a class structure that’s got them down to begin with. You’re always spinning your wheels, because that class is always going to exist as long as the other class exists. But if you’re in a socialist country like Cuba, they profess those values of classlessness. Classes are almost illegal.

In your book you talk about the supreme injustice of the American judicial and prison system. You say it’s the worst in the world. You really believe that?

Abbott: Oh yes, definitely, I believe that.

You don’t think that Russia, as a police state …

Abbott: People who do comparisons like that never check. If you checked, you’d know that in America they have the most criminal laws. And they have the most people in prisons, who are also given the longest sentences in prison. The only thing that comes close is what the Afrikaners do to a certain class of blacks.

On the other hand, Iranians cut off the hands of people who steal food.

Abbott: All right. I’d rather have my hand cut off than serve life in prison. If you want to know. If you’re talking about raw revenge, I think that’s more just.

In Moslem countries, they also stone prostitutes to death.

Abbott: Well, I don’t know if they do that. But even if they do, even if it’s common, I believe that this country has the most unjust legal system. What they did to send me to prison was just a big show.

What has been the impact of your book on your fellow prisoners?

Abbott: The inmates are mad at me because I said some things that are very painful for an inmate to realize. They’re upset over it. And white inmates hate it. The black inmates, they like it. Mexicans like it; Puerto Ricans like it.

Why do blacks like it?

Abbott: Because they think I spoke the truth about the relationships in prison. You see, they don’t have any psychological problems with being in prison.

Why is that?

Abbott: Jail is just part of their society. I think the statistics are that only one out of every six black men in this country hasn’t been to prison. So it’s somewhat socially acceptable. Most whites, when they go to prison, are ostracized from their society. It’s something they can’t tell their children. And so white prisoners have a way of behaving in prison. They have this big thing that they were rebellious kids, but they’re not rebellious in prison. You see them up talking to the guards or snitching on each other, and the things that they do — the sex things — they don’t want to talk about them or anything. They block them.

But blacks see prison as oppression, the same as they see society. It’s not because they’re black, it’s because they’re working-class people. The whites are working-class also, but they lord it over the blacks. The blacks, though, generally exhibit more compassion, more understanding.

“I shouldn’t be compared with the Boston Strangler…. People might not agree with it, but it’s not such an outrageous, inhuman act that requires that all this hatred be directed at me.”

To each other?

Abbott: Right. There are exceptions, of course, but they’re not so quick to make judgments. They understand games, know how to play the man. A long time ago white convicts knew how to do that, but they don’t do it anymore. I’ve seen the changes, the case workers coming in, the whole changeover. It caused a big shake-up in my outlook when I started reflecting on this, how black guys play the guards without feeling compromised or anything.

How have prisons changed in the last few years?

Abbott: Ever since the civil rights movement in the sixties, the minorities have been filling up the prisons.

And have prison regulations changed since the so-called reforms of the seventies?

Abbott: No, no. The means of discipline has changed. The relationship between inmates and guards has completely changed. Guards know everything about prisoners now. When I first went to prison, before these reforms, they didn’t know anything but the vital statistic about a prisoner. Now they research their lives, they keep an update on who everyone’s friendly with. They have everything down pat. They know who’s arguing with who, and then they send inmates around to different prisons to cause certain effects. They’ll transfer prisoner X to a new prison because they know prisoner Y is there and that it will have a certain effect. They want the prisoners to rebel. They do it all very consciously. This is the Bureau of Prisons people. It goes all the way to the top. Norman Carlson, the director, is involved in it. They’re always trying to arrange things so that they can cite statistics about how tough their prisons are and how many problems they have and how much money they need, how much help they need, how many guards they need, how much equipment they need.

Why do they do all this?

Abbott: I’ll tell you truthfully about Marion. I think they want to tote guns inside Marion. They’d like the gun rails that they have in the California prison system so that the guards with guns would be behind the rails and they could just take out prisoners anytime they wanted to.

You once said about your life at Rikers: “They’ve got every day of my life computerized so if they want to show I’m insane, they push a button and get all the information that supposedly indicates I’m insane but they can also turn that information around and prove that I’m an incorrigible criminal.”

Abbott: Right. It’s true.

How do they do this?

Abbott: They use case workers. They’re always preparing dossiers out of inmate records. They will prepare it in such a way that at any given time they can project any picture they want. And this in turn is used to justify anything they want to do with an inmate. And so when they’re in court, they can bring out anything they want. Whenever somebody looks at my prison record or any inmate’s prison record and thinks they’re going to learn anything, all they can really see is that we’ve been really fucked around bad. It’s all very dehumanizing, there’s no question about it.

What would you do if you could revamp the prison system?

Abbott: The way I look at it, I think you’ve got to protect society from the police.

That doesn’t answer the question.

Abbott: I believe in rehabilitation; I don’t believe in punishment. I believe in educating people in a way that you might call brainwashing.

How would you apply this?

Abbott: Well, you get someone who’s committed a crime and you talk to them over a period of time and you explain — you bring them to a consciousness of what they’ve done wrong. You tell them where they made their mistakes and tell them that they won’t do it again. You get them to agree that certain things are wrong, and then they understand these things. Then you turn them loose and they don’t do it again.

This is what you would do if you were put in charge of the Federal Bureau of Prisons?

Abbott: It wouldn’t work in this country. What I’ve just explained involves the whole justice system. It would be impossible without revamping society as a whole. It would require a revolution. The whole thing about revolution is the rehabilitation of society. And the main premise is to do away with class differences.

You’re coming back to a Marxian analysis: that the poor are taken advantage of, the middle class is scared and afraid of a fight, while the rich continue to pull all the strings?

Abbott: Yeah. The rich are the most criminal. Their attitudes are just incomprehensible to me. It astonishes me, knocks me out. Like I said, if I were released I’d either leave the country or go back to Texas, where people don’t open their mouths, or to Utah or Colorado. Out west, folks leave each other alone; they don’t bother you unless they’re gonna do something to back it up. If somebody does something wrong in one of those communities, it doesn’t matter how much money he’s got. If he’s carried himself badly he’s not gonna get by, even if he’s got the law on his side. In New York City, though, people can get away with anything.

What is prison like for you now?

Abbott: Well, the federals may be sending me back to Marion, where I have a real problem. I had to give a statement to the authorities when I was there before and a lot of people misunderstand this. The kind of information I gave there they already knew. The people I identified, they had their names already but it had all gone too far. Now, if they send me back there, I have to face the guards. And I know how they can manipulate inmates.

How have you been treated since you’ve been back from Otisville? Here in Springfield?

Abbott: Oh, like a piece of shit. I’m in the hole. It’s a strip cell. They’ve got a sign on my door that says “Highly Assaultive” and “Very Dangerous.” And I know that this is very provocative to these rednecks out here. They don’t let me out of my cell unless I’m handcuffed. I have four guards on me.

You’ve expressed a fear of being killed if you aren’t put in protective custody. How likely do you think this is? How great is the risk?

Abbott: Well, it depends on what I do. It depends on what I do to foresee it and to stop it. If I hadn’t been able to foresee things in this way, they’d have killed me a long time ago. But I’m going to try my damnedest to keep on living. It bothers me that I might have to do something …

Take someone out before they get to you?

Abbott: Yeah, and they know that. It’s why they won’t let me out of my cell here at Springfield unless I’m handcuffed. They’ve got a rule in the Bureau of Prisons that if one inmate stabs another, the guards are supposed to stand back and just tell the guy to put down the weapon. That’s how they kill people in Marion all the time. They don’t ever jump in with clubs to stop nothing; I’ve never seen anything like that.

You’re talking about being set up, specifically by the guards?

Abbott: If I get offed, then that’s whose fault it’ll be, the guards’. It’s a routine that they do to inmates they want to see hurt. And the thing is, every prison I go to, the guards are gonna hate my guts. If the Federal Bureau of Prisons gets its way and sends me to Marion, I’ve got to be very careful.

Marion has replaced Alcatraz as the maximum-security prison in the federal system. Likewise, it has the reputation for being one of the most violent penitentiaries in the country.

Abbott: It is. The guards there, they would even do it themselves. I’ve already made a suicide gesture — they’ve got it on record — and at Marion, they’re not above going into an inmate’s cell.

You’re saying something very serious now.

Abbott: I know I am. And I stand by it because guards have hanged friends of mine before. A guy I knew at Leavenworth, who took some hostages during a take-over attempt. A guard was killed. Afterwards they couldn’t deal with him. They said he committed suicide, hanged himself in his cell, but the whole population knew he didn’t. They wouldn’t give him an autopsy, which they’re supposed to do by law. He’s buried in Brooklyn. The funeral was paid for by the federal government.

It’s total anarchy, totally lawless? Isn’t there anyone in the prison system with conscience, a respect for individual rights?

Abbott: Well, surprising as it sounds, the most easy-going people I’ve ever seen in these places are the kitchen workers who come in from outside.

What about the prison chaplains?

Abbott: Oh, they make me sick. They see so much and they don’t do anything. I don’t trust religious people. I think that they entertain a lot of fantasies, probably of a sexual nature — a lot of real sick things. I had a Catholic priest up in Marion walk right by me and refuse to look at me laying on the floor. I had been beaten and he refused to even see it.

The question in people’s minds is, Should Jack Abbott ever be sent back out on the street?

Abbott: The issue is really whether I can handle myself in society. Can I? I’m not sure. People better stay away from me. I’d have conflicts, there’s no question about it. I wouldn’t solve them by killing people, though, because that’s not the thing. Not unless someone came at me first. If somebody threatened my life, I’d kill them.

Anywhere?

Abbott: Anywhere. If I was outside and someone did something to me, what am I going to do? Just stick my hands in my pockets and say, “Well, I can’t call the police on you and I can’t sue you, so just go ahead and walk off with my stuff”? I’m not going to stand there and take it like a bitch. You see what I’m saying? I’m not saying I’m going to kill someone, but I’m going to figure out methods, even if I have to get the Mafia to go to work for me — that or take a ball bat and work someone’s legs over or go bust up his house. There’s a certain type of lawlessness, of anarchy out there in society, which is just vicious, totally incomprehensible to me. I’ve never seen anything so unprincipled in my life.

What, then, do you see as your options now? You’re looking at upwards of twenty years.

Abbott: Well, the only thing I’m going to do is try to keep going. I don’t really think I’m going to be in prison that long. Besides, I’m writing. Every day. I’ve probably written about a thousand pages already, in journal form. One of my problems is that here in Springfield, they only allow me to have one two-inch pencil each day. I’ve had to make a deal with a guy just to get it sharpened.

Will your next book be fiction or nonfiction?

Abbott: Probably a little of both.

Is it about prison?

Abbott: There’ll be some of that, but it’s partly about the streets also. It will be more philosophical, more my reflections on things around me. The way I think the world is, the way I see things. But coming back to your question: I’m gonna hang on. I’m gonna make them kill me. I’m not going to give them the easy out of suicide. At first I was worried, because I thought that if I had to do something, it would just give the press more grist to grind out their little charges that I’m a psychopath. But I’m going to fight back now. I don’t care what they say.

Fight back how?

Abbott: With my work, my writing. And if anybody comes to me with anything, I’m going to bring it to him. The guards, the inmates, I don’t give a damn. I don’t care what the press says either; I’m going to stay alive.

The Jack Henry Abbott Epilogue

Perhaps as one might expect, Jack Henry Abbott committed suicide in 2002. It’s lonely at the bottom too.