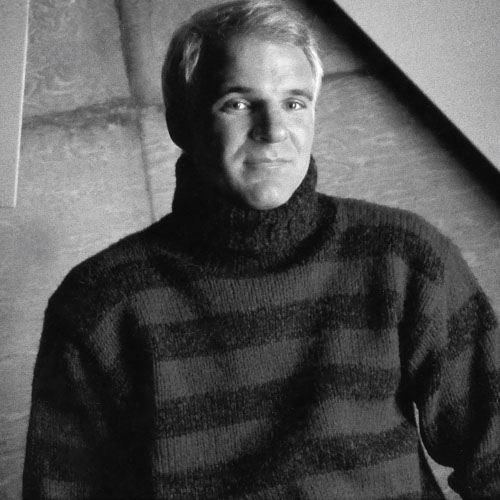

For the King of Late Night Comedy, the best place is halfway between where you left and where you’re going. But for millions of his fans, he’s already reached that destination.

King of Late Night

“I think there are very few things that are more fun than making 500 or 1,000 or 2,000 people really laugh. Jerry Seinfeld and I always used to laugh about why you would take a vacation when you should just go somewhere and do your act. What would be more fun than that?”

No plume of smoke arose from the NBC studios in Burbank, California, last May to signal a succession in that network’s late-night papacy. But when James Douglas Muir Leno took over as host of “The Tonight Show” after the 30-year reign of Johnny Carson, it was an event that fairly cried for pomp and circumstance.

What the hell. For 30 years Johnny Carson had made the show a television institution, not to mention a thriving business proposition. According to Broadcast Advertisers Reports, during the 1990 — 91 season, “The Tonight Show” netted $98 million in advertising revenue.

That success meant that as the man who followed Carson, Jay Leno bore the cachet of comedy big — time: A fellow doesn’t get to occupy that late-night chair in Burbank without it being understood that he knows how to crank an audience for laughs. In Leno’s case, that legitimacy is grounded in decades of working before live crowds all over the country — from jerkwater comedy clubs to the neon — bright Las Vegas casinos.

Along the way, Leno has won a reputation for dependability. As a comedian who speaks plainly — and with language free of obscenity — about the everyday stuff of life, his material is accessible to all sorts of folks. Listen: “In New York City they’re handing out condoms to high school students. Gee, I thought it was a big day when I got my class ring.”

“People laugh at Ted Kennedy, but how many other 61-year-old men do you know who still go to Florida for spring break?”

“McDonald’s now has 16-year-olds and 60-year-olds working side-by-side. It’s part of their cradle-to-the-grave minimum-wage program.”

For Leno the road to late-night stardom began in his hometown of Andover, Massachusetts. The son of Angelo (an insurance salesman) and Catherine (a housewife), Leno was a classroom cut-up who used humor to enliven an educational experience that seemed otherwise pointless to him.

Yet for lack of anything better to do, he enrolled at Emerson College in Boston, and while there began to try stand-up comedy, regularly driving to New York to test his material in showcases like Budd Friedman’s Improvisation.

Back in Boston he occasionally landed low-paying gigs, many of them dispiriting enough to discourage ordinary ambition. But not long after Leno graduated from Emerson, he quit his day job working for an auto dealership and headed to Los Angeles to roll the dice as a full-time comedian.

By 1977 he had made it to “The Tonight Show,” the first of several stand-up appearances there. But when he found his impact diminishing for lack of material, he took his act out on the road. Through the mid 1980s he was one of the busiest working comics, doing as many as 300 performances a year. That willingness to ply his trade paid off. Leno created reams of material and developed the ability to please a wide audience.

What made Leno so appealing to NBC executives as the heir apparent to Carson was his demographics. As a regular guest host, the likable Leno not only held the graybeard constituency that favored Johnny, but broadened the audience to include the younger viewers who had previously steered clear of the show.

For all that, Leno’s first year as host was not an easy one. As the successor to Carson, he was often a target. From late — night rival Arsenio Hall — who was quoted as saying, “I’m going to treat him like we treated the kid on the high school basketball team who was the coach’s son …. We tried to kick his ass, and that’s what I’m going to do — kick Jay’s ass” — to reviewers who faulted him for doing “soft” political material, Leno was under the gun.

And of course there was NBC’s wishy — washy support during the combustible David Letterman affair. When Letterman — whose “Late Night With David Letterman” follows Leno on the peacock network — let it be known he was thinking of leaving NBC, Leno was left to dangle in the wind while his bosses decided what to do about Dave. You remember Letterman’s snit over being bypassed for Leno as “The Tonight Show” host and how his discontent encouraged a bidding war among other networks for his services. That left NBC to decide whether or not to appease Letterman by jettisoning Leno. Well, ultimately NBC let Letterman defect to CBS — his stint at NBC ends June 25. But NBC’s belated endorsement of Leno was hardly a siren cry of loyalty. Still, to paraphrase Chevy Chase, Leno is running “The Tonight Show” … and you’re not, Dave.

With Leno headed for his second season as host of “The Tonight Show,” Penthouse dispatched Phil Berger to Burbank to hear what was on Leno’s mind.

Were you bothered by the indecision at NBC about whether you or David Letterman would host “The Tonight Show”?

No. I’ve been in this business a long time, and the nice thing about being a comedian and working on the road is, everything that happens is your own fault because you control your own destiny. It’s self — serving — you’re the writer, the producer, whatever — but again, you hold all the cards. This TV thing is an extra thing. If it worked out, great, and if it didn’t, fine. I didn’t feel so much I was left hanging in the wind. I think it looked a lot worse in print than it was, only because NBC had screwed up their handling of David once already and they were trying to figure out how to keep David here. They had given me the show, they signed a contract. “Well, how do we keep David? Let’s … “ and they kept stretching it out until they finally realized Oh, gee, this isn’t going to work.

So you didn’t feel any agita?

You know something, I would be lying if I said I didn’t. I was fairly confident throughout that we would be okay. I mean, again I did what I do when I’m on the road — you go to the audience. I’d say to myself, okay, there are 212 or some NBC affiliates, and — this is real odd to me — a lot of people criticize me because they say it’s politicking, but you have half a dozen executives you could go to or you could go to the 212 stations that buy you and ask them, Are you guys happy with it? Is this working for you? The numbers came back good, the ratings were good, the ad revenue and the demographics and all that were fine. They all seemed happy with the show we were doing.

Are you talking about particular stations across the country?

Yeah, I’d call the stations, because I don’t go where I’m not wanted and I’m not on every affiliate, but close, and say, What do you guys want? Should I go? Should I stay? Where do you see it? And unanimously — of course, they were talking to me, but believe me, these guys were businessmen; they would say we feel you should step aside if that’s what they wanted — they all seemed to be saying, No, no, we like it, we’re fine, everything is going great, please don’t mess with the show. Some people had their own suggestions — too much of this kind of music, not enough of this kind of music — okay, that’s fine. But for the most part, they all seemed reasonably happy.

The situation was, David had made a tremendous amount of money for the network, been here for ten years, was a very strong, solid performer with a proven track record. My track record was only six months old, if you don’t count all the guest-hosting stuff, so it could have gone the other way. I was fairly confident that it wouldn’t.

What’s your reaction to David going over to CBS in the same time slot?

Well, I think it will make everybody better and sharper. I didn’t have any problem when I used to go to the Comedy Store and the lmprov, and I still do it. But when I was starting out, all the comics would say, Oh, jeez, I don’t want to go on after Richard Pryor, I don’t want to go on after Robert Klein, I don’t want to go on after David Brenner. But I used to think, jeez, that’s the spot to go on, because if you could hold that audience after those guys had gone on, you’re doing pretty good. That’s how you know you’re getting better. I mean, to me, too many comedians lead the sheltered life where they go, Well, I only play colleges because they’re the ones that like me, or I only play cruise ships, or I only play Vegas. I don’t want to go to … You know the minute they face an audience that doesn’t like what they’re doing, they run and go back to the audience that liked them. My attitude was always, when you start doing well somewhere, get the hell out. Move on to the next town.

Who will get the ratings?

I think you’ll find when David moves down in time and “The Tonight Show” and “Nightline” are on, the number of people watching late — night TV is up because there’s more stuff on. If David’s got somebody that’s exciting, you’ll watch David for a while, then maybe you’ll click back, you know what I’m saying? David is classy and he’s funny and he has good taste and good standards. It’s not a show that I would be embarrassed to get beaten by, if that’s what happens. But put it this way: If you’re losing to “Studs,” you might as well quit the business.

Being a guest when Carson ran “The Tonight Show” wasn’t always easy for you, was it?

No. I had done “The Tonight Show” a few times, and like most new comedians in the seventies, first time is great, second time is okay, third time is fair, and the fourth time is probably fair to poor. It is something I warn comedians about all the time — that it’s diminishing. You’ve got to start off strong and get stronger. Anyway, after about the fourth time, they weren’t really thrilled. I hadn’t made a mark, I hadn’t gotten a series, I wasn’t that good. I think what I had perceived as my next shot was stuff I wouldn’t do in the last one. They weren’t calling, and I wasn’t calling them. It was my fault, I’m not blaming the show — I wasn’t as good as I should have been. Plus, I was very joke-oriented. I wasn’t a wise guy or a smart guy, the way I would be in a club, because I always felt this great reverence towards Johnny Carson. I would sit down at the panel and go, “Oh thank you, Mr. Carson.” I was way too polite. I felt awkward being on a first-name basis with Ed and Johnny. It seemed odd to me because I was a kid and these were men and well respected.

They were more like icons?

Well, yeah, you know, I couldn’t tease them, and Letterman was the first show where everybody on the show, including David himself, was about my age late twenties, early thirties. If I said here’s a thing I want to do, they would get it. It’s a bit like trying to do a “Saturday Night Live” sketch in prime time, because a lot of times their sketches might not have an ending, but they have these funny, quirky things that are just indigenous — is that the word? — to this particular generation. You either get it or you don’t. It isn’t a payoff kind of thing. Letterman was the first show where I’d really go on there and make fun of the host. I would sit down and go, “What a dump this is!” and David would laugh, and then I’d needle him. Where I’d feel Oh my God! if I did that with Johnny. I’d feel, jeez ..

Has anything surprised you about this first year as host of “The Tonight Show”?

Yeah, obviously, a lot of things could have been handled differently. I’m more comfortable now to take a much more active role in the show than I had been before. I enjoy the sort of executive producer part of the show, although I don’t have that title nor do I want it. When I first started, people said we don’t want you involved. We just want you to concentrate on the comedy and don’t worry about this and that.

I honestly believe we wouldn’t have had a lot of the problems we did had I been more closely involved from the get-go.

Did you always dream of being where you are now?

I came from a small town in New England, where you didn’t think in terms of going into show business. Show business is probably the only business where people who know nothing about it feel free to give you advice. I remember I had expressed some interest in it, and my friend’s mom said, “You know, you can’t be a comedian unless your father was a comedian — they have a comedians’ union.” I just said, Really, is that true? “Oh yeah, in Hollywood there are all these stagehand unions you can’t get in unless your father was one, so if your father was a comedian … “

So you did have some interest?

I was always interested in it, but it was never a viable alternative to getting a job. Quite recently, about five years ago, I was back home visiting all my friends, and my friend’s mom said to me, with all seriousness, “Now, if the comedy thing doesn’t work out, do you think you’ll come back and try to find something in our area?” I mean, she was legitimate. She meant, God bless you, you’re doing good, but if it doesn’t work out, do you think you might move back to our area and try to find something steady and regular?

Did you always know you were funny?

I remember always having the ability to make the teachers laugh. In fact, I’m still friends with most of my high school teachers — that’s the fun thing about coming from a small town. My wife grew up here in the San Fernando Valley, on the other hand. Not only is the school not there anymore, the hill it was on isn’t even there, and the street is rerouted. It’s like every six months Los Angeles goes into the witness — protection plan. Everything changes. But when I go back to my hometown, most of my teachers — if they have not retired — are just stepping down now.

Did you get into much trouble when you were a kid?

Car stuff, but when you grow up in a little town it’s so different. I remember a friend who went around and put sticks of dynamite in mailboxes. The cops would just pull him over and say, “Okay, where’s the dynamite? Okay, go home now, you crazy kid.” Today you’d of course be a terrorist.

When did you really start in comedy? Well, in college I had a roommate named Gene Braunstein. We’d laugh at the same things and we put some bits together and then we started going out and playing the coffeehouses in Boston. There was an ad in the newspaper that said, If you think you’re funny, call this number. It was for an improv group called the Fresh Fruit Cocktail. So I auditioned and got it, and Gene didn’t. That improv group only lasted about six months, and by that point I didn’t like the idea of having to always depend on six other people. So I auditioned at New York’s Bitter End.

What happened?

They said to come back during the week and work for free. My father said, “They’re not paying you? Give me his number, he’s got to pay you!” I said, No, Dad, don’t call the guy, please don’t! So anyway — I’ll never forget this — I get there on a Tuesday night and there’s about 14 people in the audience. Unbeknownst to me, of course, my father’s called all the Italian relatives in Boston and New York to tell them I’m going to be at a nightclub making my debut. So I hear all this commotion and I look and I see my grandmother, who speaks no English. I see my uncle Louie, who’s got this big coat and looks like something from The Godfather. He’s shouting, “What do you got to drink in here? What kind of drinks you got in here?” Meanwhile, this guy’s singing onstage and the MC’s asking, “Who are these people? What are they doing here?” All they had to drink was a sort of herb tea, you know, those hippie drinks. And I remember my uncle Louie — ”What the hell kind of drink is this? You can’t get a drink here? Scotch and soda?” It was just like a nightmare.

So I go onstage, and they’re sitting right in front of me, and I just stumbled through my act. It was just like a nightmare, hysterical.

What was the New York comedy scene like in the early seventies?

It’s interesting, because even the funniest comics you’d see, five years later they’d be doing the exact same act. I mean, it hadn’t changed, it was the same thing. The parts that didn’t work still didn’t work, and the things that worked okay never got any better. Come to think about it, that’s the strange thing about comedy. There are people that the first day we go, boy, this person’s good — and they never get any better. Then there are others. Like the first time I saw Andy Kaufman auditioning — oh boy, I felt so sorry for this guy. Of course, he became a huge star.

Talk about some of the rough gigs you took in those early days.

One night at the lmprov, a guy comes up and says, “Look, I’m introducing a new product to a bunch of drugstore dealers called Freshen.” It was from Japan … soft, moist towelettes you were supposed to use to avoid embarrassing rectal odor — that’s what it said on the side of the package. He said he’d pay me $75 to be at some hotel in New York where there were going to be 75 guys, and I would be introduced as the director of marketing. So I get a suit and tie on, and I get there, and the drugstore guys are just not interested in this ridiculous product. So the guy says, “Let me bring up my marketing director. “ Of course, I get up and I mention the product a couple of times and then I just go into my act — you know, McDonald’s and Nixon, what a jerk — and they just look at me. Nothing. Not a laugh. Then this guy stands up and says, “Of course, that was not a marketing director, but Jay Leno, a professional comedian.” Nobody applauds, and I just hear the crowd go, Professional comedian? Professional my ass! Then the guy says, “Who would like to be the first to sign up? We’ll give a special deal to you.” But they just sort of leave one by one. Nobody signs, and then the guy goes, “Look, I’m telling you, it’s a hell of a deal. Look, let me level with you — I’ve got a warehouse in Jersey filled with a hundred thousand cases. Just take it — take it for free!” And he starts yelling at them, and I’m waiting to get my $75. Finally I said, Can I have my money? “Get out of here! Take a case of Freshen!”

Those were the days when you sometimes worked strip joints. What was that like?

Well, at that time there were two types of strippers: There were the ones that were over 40 who showed up in the morning with a work belt and power tools to put together their clear plastic champagne glass that they were going to take a bath in. These were women who made $1,000 a week by not being able to type. This is 1970, ’71, ’72, and although the women’s movement thing had started, these were women of a different era. These were women that made real good salaries and they invested it. They weren’t hookers, they weren’t prostitutes by any stretch of the imagination. Not to say there weren’t some that probably were, and there certainly were those that were ditzy and silly, but some of them were single moms and just women who … could either work in a fast food restaurant or make $1,000 a week doing this. And they were very protective because I was a kid.

Protective of you?

Yeah. I was onstage one night doing my act, and this guy was heckling me. I was working with Lily Pagan and lneeda Man, and lneeda was taking a bath in the champagne glass. And some guy was heckling me, like real bad, mean, and I remember she just got out of the bathtub soaking wet, walked over, just punched the guy in the face, and knocked him right out of the chair.

You said there were two kinds of strippers.

Some of the women — the ones who were like 18 or 19 — they would spend hours on their acts. I know this one girl who put together this little outfit, a little six-gun Annie Oakley kind of thing, topless with a little skirt, and she practiced twirling her six-guns for hours, really thinking that the guys would be impressed.

Like anybody cared that she could twirl these six — guns, but it’s amazing how naive you are as a kid.

What do you mean?

I remember I was talking to this one girl and she said, ’’After the show, come in the dressing room.” So I walked in and she’s completely naked, and I was like, how you doing? I was thinking, Gee, should I ask her out or should I … You know, as a kid you’re just so naive. It doesn’t hit you that the woman’s completely naked, she’s asked you to come over, and you’re thinking, I don’t want to be too forward, so what’s the right way to do this?

So how’d it end?

Nothing happened, of course. I had an incident like that when I was working at the Rolls — Royce dealership in Massachusetts. I was 19 years old, and you don’t see the opportunity when it’s in front of you. I was supposed to drive this wealthy woman home, she was exactly what you would expect — Chestnut Hill in Boston, very wealthy, had brought the car in to be serviced. I was the wash boy and I drove her home, and she was attractive, but she was like 38 — 1 mean, so much older than me. She kept saying suggestive things, which of course went right over my head, and we get to the door, and she said, “Well, would you like to come in?” I said, Oh, gee, I’ve got to get back. Nice meeting you, Mrs. So — and — so. And then she just went, “Nice meeting you, “ and she gave me this real toasty handshake. On the way home, I realized, Gee, I wonder if she was coming on to me? You’re so stupid as a kid, it goes right by you. You have no idea.

Your next move was to L.A.?

As soon as I got here, I realized, Well, this is where I have to be. I’m probably the only person I know that loves L.A., but I do. I always felt that I should go to the next place, and this seemed like the next place. It’s just very odd to me to come here with a fairly conservative background and just sort of be a voyeur watching everything that goes on. I remember when I first got here, I didn’t have a car and I’m hitchhiking on Santa Monica. Some guy stops. “Hi, how you doing? Century City?” and then he’s got his hand at my knee. “Oh,” I said, “I’ll get off here.” That guy’s weird, I thought, and I put my thumb out again. Another car stops, same thing. “Where you going, Century City? Oh, good, so why don’t you slide over?” I said, “What?” “Why don’t you slide over here?” “Slide over? I’m okay here.” I didn’t have the slightest clue. I get out, I still have no idea. Another car stops, and as we go along, this guy starts talking the same way, and we pass a guy who is wearing just a leather thong bikini with one of those leather hats on. The driver says to me, “That’s what I like about youyou’re not as obvious as that guy.” “As obvious as what guy? What do you think is going on?” And I. realized, Oh jeez, these are like gay hookers. They think I’m a hooker. Hey, what did I know? Everybody in Boston hitchhikes. It took me three car rides to realize what was going on.

What made you move to L.A.?

It was around 1972, and I was in Boston watching “The Tonight Show “ right after it had moved to L.A. And I saw this comedian who I thought was terrible. So I said, that’s it. I took some cash and stuff and I just walked out of the apartment and I got on the plane and went to California. I just left and never went back for anything. It seemed to be the right thing to do.

Is it true that NBC tried to change your appearance in those early days?

Yeah, that actually happened. I went to an NBC casting meeting before I did “The Tonight Show,” and they thought I should be blond. I remember someone said, “You know, you should get your jaw rehung.”

And I thought, well … “We break the jaw and we rehang it and set it and give you this and this.” And I said, Okay, how long before I can talk? “Oh, no longer than a year, maybe a year.” I said, A year? I can’t talk for a year? “Well, maybe nine or ten months, probably a year.” How could you not talk for a year? But the strange thing about show business is you feel like Huck Finn at his own funeral — people talk about you in front of you as if you’re dead. You sit there with agents and managers — ”He’s just not attractive enough for television on a regular basis. Maybe if his hair was blond and you broke his jaw ….

What was their motivation?

Helpful advice. “We just feel you would be frightening to children. You’re very dark, you have very dark features. We feel that you would be menacing to young people.”

While living in L.A., you were doing 300 gigs a year. How do you have a social life with a schedule like that?

You don’t. Occasionally, you get lucky. Among comedians there are certain things — you know you’re going to do well any time a woman says to you, “How do you remember all that stuff?” Well, that’s it. You’re in. I talk to Seinfeld, and we laugh about the early days on the road. That’s the standard, whenever a woman says to you, “How do you remember all that stuff?” Well, that’s it. You scored already.

How did you get so into cars and bikes?

If you came to my house, and if you didn’t know what I did for a living, you’d probably think I was in the car business. I don’t have show — business memorabilia. I always liked cars and motorcycles. I always liked things mechanical. I mean, to me, the best place to be is always halfway between where _you left and where you’re going. I mean, my most fun part of the day is driving to work. Because you’ve left one place and you’re not at the next place.

Do you know how many vehicles you have?

I’ve got about 40 motorcycles and about 16, 17 cars.

And what’s the pleasure in collecting them?

Well, if you’re not a car guy, it’s a bit like trying to explain heterosexuality to a gay person. “What is it, the breasts do what? They’re very attractive, they are? Do you view them or touch them?” You either get it or you don’t. I mean, I would have liked to have been a great machinist or a great engineer, but I just don’t have the patience for it, nor the talent. There is something that comes with working with your hands that gives you a sense of honesty that you don’t get in other sorts of professions.

Are there any other pleasures in your life?

No.

Who would be on your all — star comedy team?

Oh boy, you’ll get me in trouble on this one. Well, you know, there are people who are good comedians and then there are people who are really funny. I mean, there are people who can sit down, know what they have to do to go on television to get something to work, and then there are people who are naturally funny Seinfeld makes me laugh. You know, when I talk to Jerry on the phone, inevitably I come up with something I can use somewhere because it’s just an ad — lib, and I think he does, too. One spurs the other on.

You trigger that in each other, you mean?

Yeah. You know, you just have conversations and it’s just stupid. We just make each other laugh. Anyway, getting back to the all — star team: Letterman, certainly Letterman. My friend Jimmy Brogan, a writer on my show. Brogan’s very funny. Robert Klein was always to me the epitome of a great comic. George Carlin certainly. If I go past ten, I’m going to be leaving out, I’m sure, a lot of funny people, but I mean, those are the ones that make me laugh. Carson, certainly, of course. Paula Poundstone is dynamite.

What gives with you and Arsenio Hall? Are there problems?

I don’t have any real problem with Arsenio. I like him. His is the first show to come along and seriously threaten in late night. I don’t know how that whole thing got out of hand. I honestly don’t know how it got so crazy. He seems to think I fired the first shot; I sort of thought he did. When we talked last August, we sort of agreed we each think the other’s to blame. And since that time, we really haven’t talked that much about it. I ran into him in the fall and said, Listen, some things went down on “The Tonight Show” that I was not aware of. I apologize if you were done wrong or anything of that nature. Okay, we shook hands on it, but since that time, when comedians and other people have come to me and said, “Listen, I’ve got an offer to do Arsenio.” Well, do it, that’s fine. We’ll do you before, we’ll do you later. Let’s just try and put at least two or three weeks between appearances. And since that happened, I don’t think we’ve had any problems. I would like it to be a better relationship, and I think as time goes by it probably will.

On the other hand, you still have a problem with Andrew Dice Clay.

Is he a nice person? Is he a nice guy? Yes, he is a nice guy. But I didn’t like the public persona of the act. It bothered me. I don’t know what’s worse, actually being that way or pretending to be that way to make a living. I’m sure he doesn’t understand my viewpoint either. He’ll tell you it’s just a character he’s playing. Andrew is a nice guy. I knew him at the Comedy Store, and I genuinely liked him and told him once, I like you, but I hate your act. Of course, when you say you hate someone’s act, it’s like saying they’ve got an ugly wife.

How long do you want to continue doing what you’re doing now?

Oh, I’d like to do it for as long as they want me to do it, and then go back on the road and tell jokes.

How did you meet your wife? From what I heard, it sounds like maybe opposites attract?

Oh, it is opposites attract. I was always one of those people who tried to go out with women who were smarter than me because I have that much going for me, and anything else I can bring to the party. I met Mavis at the Comedy Store. She was in the audience and I saw her. The Comedy Store is small, and in the back there’s the rest rooms, and eventually women have to go. So I followed them and waited outside, and that’s kind of how we met.

You ambushed her outside the bathroom?

That is probably the correct word. Yeah. I mean, we are opposites, but we do like the same things. We have the same taste in furnishings and houses and things of that nature, and she’s very, very bright. I always take her advice or ask questions, and she reads a tremendous amount — at least 15 books a week. I’ve never met anyone who could keep up with her in literary discussions.

How’s life in Beverly Hills?

Well, it’s very odd living in California. One of the funniest things to me was when I was sharpening the lawnmower blade and my neighbor — he’s a writer was looking on with amazement. I’m just sharpening the blade for the mower, I said. He goes, “Yeah, you know how to do that?” He said it to me as if I were doing holistic medicine. It just makes me laugh that most guys out here don’t know how to do anything, can’t fix a car, can’t put a fan belt on.

So you’ve come a long way from where you started.

Oh, yeah. Although sometimes I feel caught between two different cultures. I’ll never forget the time I was onstage at Carnegie Hall, and in the fifth row there’s my mother, and there’s some guy behind her just laughing, and my mother goes, Ssh, ssh. I go, Ma, don’t ssh people. I mean, she’s unbelievable. The only person not laughing, but she turned around and went, Ssh, keep it down. “Ma, let the guy laugh, he bought a ticket. You didn’t pay to get in here.” And of course, it got a big laugh. But that’s what I mean. It’s just so odd to be here and have press agents — that you pay people to go out and talk about you, trying to spread rumors and things. There are certain things I could never explain.