“Prime Minister Begin’s interpretation of Camp David was certainly contrary to the interpretation that both President Sadat and I had…. I believe that the Palestinians should have a homeland and be treated as human beings…. This issue occupied more of my time in the White House than any other foreign policy matter.”

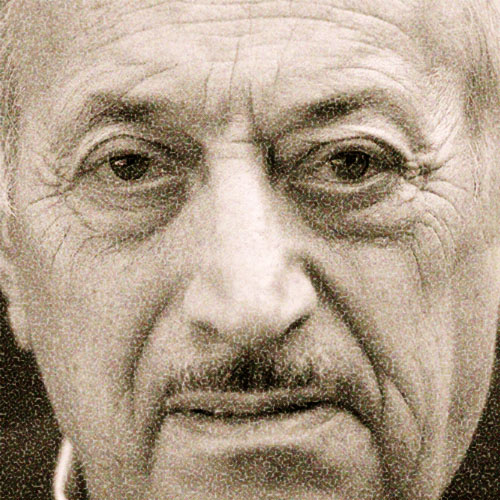

Penthouse Interviews President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter, Jr. (Jimmy Carter), joined the population of Archery, Ga., on October 1, 1924, the eldest of three rambunctious offspring born to Lillian Gordy Carter. As with Jack Kennedy, the personality of the future thirty-seventh president of the United States was to be largely forged by a strong-willed mother, the irrepressible Miz Lillian — who was later to solve the boredom of widowhood by becoming a Peace Corps volunteer in India at the age of sixty.

When Carter registered at Georgia’s Southwest College in 1941, he was, according to contemporaries, a typical product of rural Georgia — shy, a strict Baptist, ignorant of the wider world. But Miz Lillian’s boy was also ambitious, and the following year he transferred to prestigious Georgia Tech. By then the war was on, and a year later he became a middy at the U.S. Naval Academy.

Including those four years at the academy, Carter spent ten years in the navy, an engineer on nuclear-powered vessels. Part of the time was spent under feisty Adm. Hyman Rickover, the “father of the nuclear fleet.” By then, there was another strong woman in his life: he had married Rosalynn Smith on graduating from Annapolis.

In 1953, with three sons to support, Carter hung up his uniform and returned to Georgia, establishing himself as a peanut farmer in Plains. Soon, he branched out into the profitable warehousing side of the peanut business.

The ex-lieutenant became a prominent community figure, active in church and business organizations. He ran successfully for the Georgia senate in 1963, serving four years, then tried for the governorship and lost. But 1967 had a recompense — the birth of his daughter, Amy Lynn, far and away the most intellectual of the new Carter brood.

A second stab at the governorship, four years later — with his campaign being run by a rumpled, overweight student called Hamilton Jordan — was crowned with success.

Emerging from the state house in Atlanta in 1975, Carter dashed off an autobiography, Why Not the Best? (a quotation from Rickover); then he and Jordan put together the most impressive end run on the Democratic party ever seen in modern times. The result: a nationally unknown figure became president.

Today, Carter is back on home territory, in the tiny hamlet of Plains. It is a village you could drive through without noticing, if you had a good symphony on the radio. The only large sign on Main Street — virtually the only street — says BILLY CARTER’S FORMER FILLING STATION. There’s one traffic light — installed because of the press of the press and other visitors when his comfortable but modest home became the summer White House. If you keep a sharp lookout, you may spot Carter’s “office.” It’s actually Miz Lillian’s old abode, a small three-bedroom affair with a tiny yard.

The only thing that distinguishes the house from its neighbors is the trio of Secret Service cars parked outside the garage. For security reasons, visitors are ushered in through the side door, and go through a small kitchen to reach the living room — which, save for the addition of a large desk, seems not to have changed since the days when his mother lived there.

In the White House, Carter rose most days at 5:30 A.M., jogged on the South Lawn, and read the press. By the time Zbigniew Brzezinski arrived to brief him at 8:30, he had done nearly two hours’ work. His speed-reading capacity, encyclopedic memory, and reluctance to delegate decisions made him probably the most workaholic occupant of a job for which only workaholics are suited. Today, with his book Keeping Faith now launched, a visitor has the impression of a man puzzled as to how most Americans can tolerate working only forty hours a week.

As president, Carter never seemed to lose sight of the larger picture of why he was elected — to bring honesty into an office where dissembling was the name of the game, to look out for those too underprivileged to look out for themselves, to try to promote peace and check the arms race. He smiled little — except with his mouth, not his eyes, on public occasions or when a photographer was present. His own staff found him distant. He seemed more devoted to humanity than to all but a very few actual human beings. Yet Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter’s White House was probably the most gracious and “classy” since Franklin and Eleanor’s. This close, distant couple remain unchanged.

Camp David was Carter’s main bid for a place in history, the Tehran hostage crisis his nemesis. These issues took up more of his time than any other single one. In Plains, where the intellectual ether smells of football scores, beer, and peanut prices, the Middle East haunts him still — the birthplace of the religion to which he has nailed the colors of his soul, and the home of his late friend, Anwar Sadat.

He is a visiting professor at Atlanta’s Emory University — as is his Sancho Panza, Jordan. He has managed to parlay this sinecure into a round-the-clock job by planning to spend most of 1983 as a student of peace in the Middle East, traveling there to meet the leaders he knew when he was president. At former President Nixon’s suggestion, President Reagan has asked Carter to brief him on what he learns. Back at Emory, he will bring famous policymakers from his administration to talk to his students about the problems of peacemaking.

In a long interview in his Plains office (he has another in Atlanta), Carter came across as a man convinced that his loss of office was God’s will, intended to make him contribute his considerable talents to humanity in other ways. The honesty, integrity, and capacity for self-criticism that made him “flip-flop on the issues” are no longer a problem to a man relieved of the burden of the world’s toughest job.

His self-imposed assignment this year is to help bring peace to the Middle East. After that, what? Carter once remarked that he had seriously considered abandoning the presidential race and going off to South Africa to try to help solve that problem. By the time he’s gotten Yasir Arafat and a future prime minister of Israel around a table, Andrew Young, his former ambassador to the United Nations and “best friend in politics” (interviewed in Penthouse two months ago), should have finished his term as mayor of Atlanta. No one should be surprised if they go off to Pretoria together.

What are Jimmy Carter’s views on today’s economic situation?

Well, there has been a series of very bad mistakes, quite radical in nature, with enormous tax decreases, which have built-in deficits, under President Reagan, that will equal all the peacetime deficits of all the presidents that served before him for over 200 years. These deficits, I think, will be damaging to our country for the foreseeable future. There’s been a lack of emphasis on employment for our people. As you know, there are more people unemployed now than at any time since the Great Depression, and small businesses have been wiped out at a rate not equaled since that depression.

One thing that has been beneficial has been the stability of oil prices; in 1979, as you know, oil prices more than doubled. They haven’t increased substantially since, so that gives us a worldwide lid on inflation. But in general I think Reaganomics has been a mistake and has created some damage not only to our country but to other countries of the world, and I think there’s a general realization that what I have just said is true.

How do you feel about President Reagan’s defense policies? Do you think he’s spending too much money on defense and not enough on domestic problems?

Well, I think so. My career was in the military, and I am familiar with military budgets as well as any president. And it’s a bottomless pit. When I came into office the military budgets had gone down about 35 percent in eight years, and I established a policy of gradual, predictable, very tight defense budget increases each year, on an average of about 3 percent in real terms, so that there was some stability to it. And this has now effectively been abandoned by the Reagan administration. Kind of a blank check has been given to the military, and a lot of worthless expenditures have been approved, with great waste, in my judgment. So, I think it has been ill-advised, and I hope that Congress will put some corrective action on it.

Even though it’s a Soviet idea, do you think a nuclear freeze would be a good place to start from?

Well, it’s not a Soviet idea. As a matter of fact, when I was in Vienna in June 1979, with Brezhnev, I proposed an immediate freeze on the production and deployment of all nuclear weapons, and the implementation of a comprehensive test ban against any nuclear explosives, whether peaceful or warlike in nature. And at the same time, I proposed that SALT II go into effect immediately, even prior to Senate ratification, and that we have a 5 percent reduction each year in the SALT II limits.

Brezhnev rejected all these proposals because he was so eager to go ahead and deploy the very formidable SS-20 weapons in the Soviet Union. Once he got his SS-20s deployed, only then did Brezhnev say, well, let’s now have a freeze. By that time, of course, the NATO allies had agreed to go ahead with Pershing II deployment and with the ground-launched cruise missile, to meet the SS-20 threat.

So to summarize, at this moment, looking back on that as accurate history, I would think that a freeze on intercontinental-type missiles would be appropriate now, but that the NATO allies should go ahead with the deployment of intermediate-range missiles. The basic premise of all those peace moves would have to be adequate verification of compliance on both sides.

You talk in your book about the problems you had with specific interest groups. Do you think that lobbies abuse their power?

Yes.

Do you think that they go too far in their interference in policymaking?

Yes, I do. I don’t know if they are the greatest threat to our system of government, but I can’t think of a greater one. Some of these lobbies are extremely rich and extremely powerful. Through political contributions on the one hand and political threats on the other, these lobby groups are able to influence Congress substantially. I think the situation’s getting worse instead of better, and it helps to subvert, in my judgment, the intention that Congress should pay to the interests of people who are not represented by lobby groups.

Could you name some of the most powerful lobbies?

Yes. One is the military-weapons manufacturers. The B-1 bomber, for instance, is a complete waste of money. The Clinch River Breeder Reactor, which is proposed for building in Tennessee, is also a $7-9 billion-dollar project from which we will never get two cents’ worth of benefit. But the lobbies’ political influence is so great that they have so far been able to get a majority of the votes in both houses.

We tried to establish a system for controlling the unwarranted ·increase in hospital charges and costs; but the health industry has its powerful political arm in Washington and has so much money to spend in Washington that they were able to subvert this effort.

What about foreign-policy lobbies?

Here the efforts are much more open and obvious to the public. There are certainly ethnic groups in our country that have a strong influence on public policy; but in general those efforts are well known to the news media, because the issues are so highly publicized. The American Jewish group, the American Greek community, and the Taiwanese are three that immediately come to mind. They’re very influential and powerful on the issues that affect their home countries.

There is nothing wrong with this in a democracy like ours. I think it’s an advantage to our country that we do have ties of American citizens to almost every country on earth. And that kind of commitment is important. When Poland had its recent troubles, the Polish American community was the strongest proponent of action by our government to protect the freedom of the workers there. This has historically been the case, but it is less subversive and much more open than lobbying on domestic issues.

How do you feel about relations with China? There’s more talk now of the Chinese mending their bridges with Moscow.

I think there has been a very serious mistake on the part of our country, in the past two years, in not understanding the importance of our good and friendly relations with China, of the prime responsibility of relations with China. All the way from President Nixon through the end of my term, we recognized how important China was, as a friend, cooperating with us in matters around the world.

We always avoided very carefully any alignment of the United States and China, on the one side, against the Soviet Union on the other side; I think that would be destabilizing. But to maintain better trade, better understanding, better progress toward peace and stability in the Pacific, it’s obvious that our lot should basically be with the Chinese.

President Reagan early on announced that he would reject that premise and cast our lot back with the Taiwanese. I thought that was a mistake then and I think it is a mistake now. He has modified that position to some degree; but in the process, I think, a lot of the understanding and mutual confidence that had been built up has been lost.

How do you think the Taiwanese problem should be resolved?

The way I resolved it when I was president — by recognizing China, that there is one China, but expressing a hope that China-Taiwan differences be solved peacefully, and with patience, and having our dealings with the people of Taiwan through private agencies and not on an official basis.

Do you think one possible solution for China and for Hong Kong might be for them to become independent countries in a Chinese commonwealth — Chinese Canadas?

That’s one of the options that I’m sure the Taiwanese leaders have considered, but I don’t have any way of knowing which nations on earth would recognize a nation of Taiwan if it declared its own independence.

What if this were done with the consent of the mother country, as with the case of Australia and Britain?

That would certainly be one option, if it was suitable to the Taiwanese and to the people of the mainland. It would certainly suit me.

If you were able to do Camp David again, what would you do differently?

I think we should have consulted more closely with the Jordanians and the representatives of the Palestinians and perhaps some of the other Arab leaders before Camp David was begun. But of course, at that time, we had no idea what the result would be, we had no definite plans, and we were trying not to be specific in terms of a final solution in the Middle East before we started, but were just aiming for basic principles. But that — more consulting — is one thing I think we should have done.

Was the reason you didn’t invite King Hussein that you didn’t think he would come, or that he wouldn’t get along with President Sadat, or that it would just make agreement more difficult?

Well, we had a hard enough time with just two Middle East leaders trying to negotiate a settlement, without having a fourth head of state or government there. But, during the Camp David process, President Sadat talked to King Hussein and explained the basic settlement terms to him; and my report from the Egyptian leaders was that King Hussein was supportive, and that President Sadat and King Hussein would meet immediately after the Camp David agreement was signed, and [that Sadat would go to] Morocco, and I believe that [these meetings were] scheduled. But they didn’t materialize. And, as you well know, right after Camp David, I called King Hussein, outlined to him the terms of the settlement, and then sent Secretary Vance to Amman, and also to Jeddah, and he came back through Damascus. And then I answered a series of questions that King Hussein put to me about our interpretation of what the Camp David agreements meant. So I think that, subsequent to Camp David, and during it, we had the sense that King Hussein at least understood the basic terms of the agreement.

Didn’t you virtually promise President Sadat that you would bring in other Arab support?

Yes.

Which means that at the time you must have thought it was more possible than it turned out to be.

Yes, well, we had every expectation that King Hussein and President Sadat would have a productive discussion leading to Jordanian participation. And I went to Camp David with the determination to represent as best I could the interests of the Palestinians. There were some goals we had in mind, obviously shared between me and President Sadat. One was that any future discussions would include the Palestinians as full participants, along with the Jordanians. Second, that the premise of the discussion would be that the Palestinians should have a voice in determining their own future. Third, that it would lead to full autonomy for the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. And, fourth, that no final decision would be made about the West Bank and Gaza without a separate referendum to be held among the Palestinians themselves — that they would have the right either to reject or accept any agreement concerning the West Bank and Gaza that had been worked out among the Egyptians, the Israelis, the Jordanians, and the Palestinian leaders themselves. I felt that my own commitment to the Palestinian cause, to Palestinian rights, was one factor that was important, and it’s obvious that President Sadat shared my goal.

When you speak of having intended ultimately to bring in the Palestinians, and when you said earlier that you wished that you had consulted them earlier, were you thinking of Arafat or of other people?

Well, indirectly with Arafat; as you know, we had a national commitment not to negotiate with Arafat unless the PLO would acknowledge Israel’s right to exist. But when I met with King Hussein earlier, and with Crown Prince Fahd and King Khalid of Saudi Arabia and also with President Assad, in every one of my private conversations with those leaders I encouraged them to intercede with Arafat to encourage the Palestinian leader to recognize Israel’s right to exist, so that we could begin direct conversations with the Palestinians.

This was my hope and it was also my expectation for a long time, and I might say that the leaders of Syria and Jordan and Saudi Arabia and Egypt all promised to try to encourage Arafat to do this, so that we could include them in the determination of the future course of Middle East history.

Syria promised?

Yes, Syria. The concern that I had then, and the concern that I have now, is: the longer this process is delayed, the more Israel will tighten its control over the West Bank and Gaza, and the Golan Heights as well, with increasing settlements. As you know, I characterized those settlements as both illegal and an obstacle to peace, and at Camp David I was convinced that Begin promised no more settlements there until the peace negotiations had been completed. Subsequent to Camp David, he denied that he had made that commitment, but in my judgment there was no question about it.

Given the growth of the settlements since the agreement, he could be said to have dealt with you in bad faith. You twice accused him of subterfuge at Camp David.

It’s hard to say, because there’s room for a difference of opinion. You know, we had dozens of very intense negotiations, leading to agreement, and this is the only one on which, subsequent to Camp David, we had an open difference of opinion. There was an expressed target date of three months to conclude the Egypt-Israel treaty, and Begin maintained that his promise to stop the settlements was only for the three-month period.

But the Egypt-Israel treaty had nothing to do with the West Bank and Gaza.

It was certainly my understanding that he had promised to stop the settlements throughout the duration of the peace negotiations, not just the Egypt treaty.

Judging from what you say in your book, either Begin dealt in bad faith or he deceitfully allowed you to draw a wrong conclusion, or he is now simply guilty of mendacity.

I hate to attribute motives to someone else unless I am sure about them, but Begin’s interpretation of the Camp David agreement was certainly contrary to the interpretation that both President Sadat and I had. And I explained my interpretation as clearly as I could to King Hussein and to the [other] Arab leaders as an answer to the questions that were prepared and presented to me subsequent to Camp David. That series of answers, which I myself wrote, is the best interpretation that I could put on the Camp David agreement, as to what America understood the agreement to mean: the undertaking on the settlements was not a part of the agreement for an Israel-Egypt peace; it was a part of the agreement for an overall peace in the area.

What was King Hussein telling you and President Sadat during the negotiations? There were two telephone calls to the king, weren’t there?

Yes, with President Sadat, not with me. But President Sadat reported to me that King Hussein was supportive of the peace process and had no argument with the terms of the Camp David agreements as they were described to King Hussein by President Sadat at the time. But, as you know, on an open-line telephone call, it is not possible to go into the hundreds of nuances of the agreements. I think, subsequent to the Camp David agreement, King Hussein needed to have the support of the other Arab leaders as well as of the PLO in order to be a full participant — support he did not get. And, subsequent to the Camp David agreements, Prime Minister Begin felt the full pressure of political criticism, primarily from his own party members, who, by the way, until this very moment, have never supported the· terms of the Camp David agreements.

Hussein is virtually back in the same situation now, with a little more strength, because the Palestinian organizations within the PLO have little choice but to follow Arafat’s preference for negotiation over warfare. Do you see anything good likely to come out of this present situation, such as more Palestinian flexibility?

I don’t know. It’s hard to predict the future in the Middle East. I’ve never been successful so far! My own intention, as a private citizen, is to continue my study of the factors involved and to try to work for the realization of the hopes for peace during these next few months at Emory University, where I will be a professor. I will begin a one-year analysis of where we might go from now to find peace in the Middle East, and I’ll be eager to talk to leaders of the Arab countries and to the leaders of Israel and to the representatives of the Palestinians; so that I can present, I hope, to the public, the factors that exist, some of the options for action, and the benefits that could be derived from a general peace settlement.

In my judgment, the Israelis must withdraw from the West Bank and Gaza, both their military forces and their government. The Palestinians must be given full autonomy and be permitted to determine their own future. They must have a voice, a final voice, in determining the status of the West Bank and Gaza. These kinds of things would be a great step forward, and they must be combined, in my judgment again, with recognition by the Palestinians and the Arab leaders that Israel has a right to exist.

Are you saying that the West Bank and Gaza should be a homeland for the Palestinians, and that they themselves should decide on its final status, whether it’s to be an independent state, federated with Jordan, or whatever? Is that correct?

That’s what the Camp David agreement prescribes.

What about East Jerusalem?

The position of the United States government has always been that East Jerusalem is part of the West Bank.

You said in your book — and it must have been very much in your mind recently, when Jihan Sadat was here — that Sadat was the politician you admired more than any other in the world.

Yes.

His critics have said that he was vain, that he needlessly insulted leaders whose support he needed, that he was sometimes rash. Do you still accord him the same superlative of being the world’s most admirable politician?

Yes. I have my faults and Sadat had his faults. If there was one difference that I had with Sadat on a fairly continuing basis, it was that he was too impatient with, or critical of, other leaders in the Middle East; and I always encouraged Sadat, both publicly and through my private messages, to be more understanding of the problems that other Arab leaders had and to try to work more harmoniously with them. In my judgment, had Sadat survived, he, like Egyptian President Mubarak, would be extending a hand of friendship to the Saudis and the Jordanians and the Moroccans and others who had been alienated from him since his initiative in going to Jerusalem and his signing of the Camp David accords.

So, yes, I still maintain that Sadat’s boldness and his political sacrifice in attempting, in his own way, to secure peace in the Middle East was a heroic and an admirable thing.

Four years after Camp David, how secure do you see the Egypt-Israel peace treaty? How do you see future relations between the two countries? I think the relationship has been strained very severely. My judgment is that both the Egyptian and Israeli peoples want to have peace. The people of Lebanon and of Syria and of Jordan also want to have peace, and the Palestinians want to have peace, too.

But each one of those entities in the Middle East has ancient misunderstandings, ancient hatreds, and public political statements have been made by their leaders, so that this desire by the people for peace and stability and the maintenance of good relations has been thwarted. I don’t think it’s hopeless, but I’m not sure that we’ll have success. Obviously, in the last number of months, with the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the entire fabric of. interrelationships in the Middle East, including relationships between Israel and Egypt, has been torn and damaged.

You say you’ll be going to the Middle East within the next few months. Would you hope to meet with Arafat while you’re there? Since you’re no longer a member of the government, you can meet with whom you like.

That would be an option that I would pursue. I wouldn’t be bound by any oath or commitment not to do so. If I don’t manage to meet with Arafat, I would certainly want to meet with some representatives of the Palestinian cause who could explain to me under what circumstances the present deadlock might be removed.

Are you thinking of the West Bank mayors who have been removed by the occupation authorities for supporting the PLO?

Certainly, yes, among others.

What’s your assessment of President Mubarak?

I think he’s a good man. I know him well. I had many occasions to be with him while I was still president, and subsequent to my leaving the White House. My judgment is that he is a strong man, and that he is much closer, perhaps, to the domestic political scene than was President Sadat. I think he is much more attuned to the need for friendship and understanding and an easing of tensions with the other Arab leaders, and my hope is that the other Arab leaders will quickly re-cement their ties with Egypt. I think this would be better for the Arab world, for the Middle East generally, for our country, and for Israel.

What do you think of President Reagan’s so-called peace initiative? Has he simply rediscovered Camp David?

I think his initiative is eighteen months later than it should have been. But I don’t ·see anything in it that would be contrary to my own concepts of what peace should encompass. I am more concerned about the Israeli settlements than President Reagan seems to be, and I have been more forthcoming in calling for a Palestinian homeland and the honoring of Palestinian human rights than has President Reagan; and I took rather stronger action when Israel invaded Lebanon in 1978 than President Reagan did this year. But basically I think his initiative is a good move, and I have supported it.

Is the Fez Resolution — which calls for peace among all the states in the area — a move in the right direction?

Yes, it’s a move in the right direction; but, knowing what I do about the Israeli position, I think there are some elements in it that will not be acceptable [to Israel], and looking at the recent comments that Prime Minister Begin and others have made, I think there are some things there that are obviously not acceptable to the Arab leaders. But I think the Fez Resolution was a step in the right direction.

As was the Fahd plan, which calls for the implementation of various U.N. resolutions, among which was one that stated implicitly that Israel was to be recognized by the Arab states?

Yes, I think so. But, you know, it would be so helpful if the Arab statements would just say clearly that “with peace, we will recognize Israel’s right to exist.” This, I don’t think, would be giving up anything.

You mean, instead of euphemisms like “the security of all states”?

Yes, because although most people recognize that it is being said, it gives the Israelis a chance to deny that it is being said, and it keeps that obstacle there. My

position has been that it is best for the Arab cause and for the Palestinian cause to take advantage of the opportunities for the enhancement of Palestinian rights, and let the Israelis show whether or not they are negotiating in good faith.

Do you think that if the Arab leaders and the PLO announced that they were going to accept the 1947 U.N. resolution creating a Jewish state, this would cause a lot of sleepless nights in West Jerusalem?

(Laughing) I think it might.

There would be a crisis.

It would create some turmoil. In some ways, both sides are afraid of peace. I thought the Israelis made a constructive commitment in the Camp David accords by recognizing the Palestinians’ rights, their right to determine their own future as a full negotiating partner, having a veto, in effect, over the permanent status of the West Bank. That was a substantial concession on the part of the Israelis. At the time, it was rebuffed by most of the Arabs and by the Palestinians. It was rejected as not being significant. I thought then and I think now that it was significant, that rejection played into Israel’s hands; and of course some of the overtures that have been made by the Palestinians and other Arabs have been rebuffed by the Israelis. And so there is still no means by which the entire issue can be assessed in its totality, the honest differences of opinion be understood by the public, and the advantages of peace be understood by those who are most directly affected. That’s one area, as a private citizen, not having the restraint of public office — and not having the authority of public office, either — where I might be able to help. I’m not sure, but I’ll make an effort.

Would you plan to go to Syria?

Of course that would depend on the attitude of the Syrian officials; but I would like to go to Syria. I have met with

President Assad on only one occasion, with Foreign Minister Khaddam several times — but that was in Europe. Yes, Syria would be one of the places I’d like to visit.

To sum up, on your Mideast trip, which leaders are you particularly anxious to meet?

I’m not trying to ask for invitations. But I would hope to go to Israel and Egypt, to Jordan, Saudi Arabia, perhaps to Kuwait and some other Gulf countries, as well as to Damascus, but I haven’t made a final plan. There is a need for me to understand more clearly the latest ideas and thinking of the leaders of the Middle East, and I believe that I can best determine the answers to that question by talking to the leaders. themselves.

What’s your assessment of King Fahd? You knew him as prime minister.

Yes, I knew him well and I think very highly of him. I have always found him to be reasonable; he’s been a friend of our nation. He has indicated to me that what Saudi Arabia wants is peace with honor and the recognition of the Palestinians’ rights. The Saudis have never deviated, in my judgment, from that commitment to an independent Palestinian nation, an independent Palestinian state. My own judgment is that an independent state would not be the best starting approach, but that’s an honest difference of opinion.

What is your broad opinion of the situation in the Gulf now? Has it worsened since the early days of the Iranian revolution? Are the dangers greater for Iran’s neighbors?

Well, the main danger that I saw as president was that of possible intervention by the Soviet Union into the Gulf region. This is why I took as strong action as I did when the Soviets went into Afghanistan. We did everything we could, short of military action, to convince the Soviet Union that they had made a mistake, and to prevent their being successful in their attempted takeover of Afghanistan. I think that if the Soviets stayed out of the Gulf region, eventually that area could be restabilized. The Iraqi-Iranian war has now reached kind of a stalemate. I don’t know what will happen in the future, but there’s a stalemate roughly along the original borders between the two countries. I think Iran is still suffering adversely from the radical nature of the Khomeini regime. Perhaps; in some ways, the war with Iraq, even though they were not the aggressors, has taught the Iranians to limit their revolutionary attempts to intrude on the affairs of other countries, which they were doing in Iraq. If the Iranians can ever recognize that they ought to take care of their own affairs first and not intrude on those of other nations, then I think stability could remain in the Gulf.

You talked of the fear of Soviet intervention. Do you mean physically, with forces, as in Afghanistan, or do you mean in indirect ways?

Either way. As you know, in my State of the Union speech in 1980, after the Soviets went into Afghanistan, I said very plainly, and to Brezhnev privately, that any intrusion by the Soviet Union into the Gulf area would be interpreted as a direct threat to the security of the United States, and that I would take commensurate action to protect our interests, using military force if necessary. And I think it’s that serious, if the Soviets should try. So, in every way, through helping the Afghan freedom fighters, through trying to preserve the status quo between Iran and Iraq, trying to prevent disruption of existing regimes, I think our country should try to prevent any opening there for the Soviet

Union to intrude on.

The feeling among the leaders of most countries in the area is that the Soviet Union is not the worst threat. The Saudis would say that the main threat to their security comes from Iran and from Israel, and the Jordanians would say from Syria and from Israel, when talking of the actual likelihood of invasion of their territories.

Well, it depends on whether you’re talking about an immediate threat or a more serious, long-range threat. The closer the Soviets get to the Gulf, the more relationships among the individual nations would be disrupted and destabilized. I cannot dispute the fact that, in Jordan, their main concern right now would be from Syria or Israel. I can neither respond nor disagree with it. The entire region, including Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, and Israel, would best be served if we could work out some relationship between Israel and its neighbors that would bring honor to all countries, based upon the elimination of the violation of Palestinian rights. That would tend to lessen any threat to Jordan from whatever direction, any threat to Saudi Arabia from whatever direction, and also tend to keep Soviet influence out of the Near East and Gulf regions; so that one could accomplish all the goals that we have.

Part of a final agreement would be the total evacuation of the Israeli settlements?

Well, the agreement that we worked out at Camp David was that Israel would withdraw its military forces and its government and would give full autonomy to the Palestinians, and that after five years of negotiation the final status of the West Bank would be determined and it would have to be approved by the Palestinians in a referendum. President Sadat’s contention was that West Bank sovereignty did not lie in Israel or Jordan, but that sovereignty in the West Bank and Gaza lay with those who actually dwelled there. I couldn’t disagree with that premise.

Let’s talk of the current crisis in Lebanon. What would Jimmy Carter have done if you had still been president?

That’s the kind of question I like to avoid answering, because if I had been president for the last twenty months I’m not sure that events would have been the same. When Israel went into Lebanon in 1978, I took very strong action immediately, by notifying Prime Minister Begin that Secretary of State Vance would introduce a resolution of condemnation in the United Nations Security Council. We would sponsor such a resolution if Israel didn’t withdraw, and I would notify Congress that the military weapons that we had sent to Israel were being used illegally. And as a result, as you remember, UNIFIL [the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon] was formed and Israel did indeed withdraw from Lebanon. Whether that strong action would have been successful this year, I can’t say, but I would have done everything possible to prevent an intrusion by Israel into Lebanon to begin with, or to encourage their early withdrawal and a limit to their intrusion. The attitude of Secretary Haig made no sense ,to me. I think if Secretary Shultz, whom I know and respect, had been secretary of state, the United States might have taken more positive action. I really don’t understand his predecessor at all.

Secretary Weinberger believes that there should be a large U.N. force throughout Lebanon, possibly as many as 20,000 men, to help the Lebanese disarm all the militia with the approval of the Lebanese government. What’s your view of that?

I’ll put it this way: I’d like to see all the Israeli and Syrian forces withdrawn as soon as possible. I’d like to see a strong central government established in Lebanon, if possible, and whatever international forces would be required to maintain order — I don’t know how to put a number on the troops — should be used so long as Lebanon asks for them. I’d prefer U.N. forces rather than forces outside the U.N., and certainly forces that are multinational in nature.

Do you think that the present Franco-Italian-American force should stay until all the militias are disarmed and there is a Lebanese government genuinely in control?

I think that’s a political judgment that would have to be made by the Lebanese authorities, working with the Italians, the French, and the Americans. If I were president, I would defer heavily to Lebanese desires. How soon that circumstance [full Lebanese government control] can come, I don’t know, but I think that after what happened in West Beirut we should be cautious about too early a withdrawal, and make sure that the people there — all the people there, Christians, Muslims, Palestinian refugees — are protected. Having no inside information, I can’t say how long that might take.

In retrospect, would you have wished that you had consulted more with the Lebanese government? President

Sarkis was known to be looking for an invitation to come to Washington, and you never invited him.

Yes, I think that’s a subject that should have been addressed more strongly by us, and by the French and others. As a matter of fact, President Sadat brought up the Lebanese situation almost every time I saw him. This preyed on his mind. He was very worried about the Lebanese and the threat to the stability of Lebanon from both the presence of the Syrian forces and the Israeli-Christian militia forces in the south. I think it would have been better had our country played a stronger role in Lebanon.

You said in the book that Israel was more interested in the status quo than in peace, and I think most observers of the scene would agree with you. You said a moment ago that a just solution to the Palestinian problem was essential for Israel’s security as well. Do you feel that Israel’s desire for either no movement or the slowest possible movement could lead to a failure of the peace process and another Arab-Israeli war, in which Israeli territory itself would be attacked for the first time?

Yes, that’s always a possibility. The longer there is delay in trying to negotiate a final settlement, the more danger there is that the West Bank and Gaza will never be freed of Israeli occupation by negotiation alone. So I think it is counterproductive for the Palestinians and the Arab countries to avoid the opportunity for negotiations. I think Begin and Defense Minister Sharon would like to have the unrestricted opportunity to increase the settlements in that area.

You said in the book that one of the guidelines from which you started was that Israel was a strategic asset, and that of course has also been said by scores of American leaders. In what way do you see Israel as a strategic asset? Do you see its large and efficient forces as something that could be used in the interest of the United States in some way?

I have the firm belief, as I stated in the book, that it’s God’s will that there be a nation for the Jews. This is my religious belief. My own hope is that Israel will be a peaceful nation, living within recognized borders, in peace with its neighbors. If that hope of mine could ever be realized, then of course Israel with its adequate military strength can be a stabilizing force in the Middle East. It would have to be predicated on Palestinian rights, because I have the belief, as I have said many times when I was president and since, that the Palestinians should have a homeland and that they should be treated as human beings with a right to own property, assemble, debate issues, and vote; and this issue, this question, occupied more of my time during the four years that I was in the White House than any other foreign policy matter.

I think we made some progress, but the hopes that I had when I left the White House have not yet been realized. I don’t assume that they won’t be in the future. If the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza continues to be a festering sore, then Israel’s strength could be a factor for continued bloodshed, as has been the case in Lebanon.

When you say a peaceful Israel’s strong forces could be a stabilizing element — in what way? To intervene in conflicts?

No, not as a police force, but just as a center for high technology, for the development of the natural resources of the region, as a place for displaced Jews to live, as an exhibition of the workings of democracy — these kinds of things.

How does military strength fit in with these objectives?

I think the United States can handle its own military needs in the Mediterranean area; but if there should be a massive threat from outside the Middle East, as from the Soviet Union, in the future, then Israel’s military strength could certainly be a benefit in stabilizing the situation.

Such as coming to the aid of Turkey?

I’d rather not get too specific.

I take it that Jimmy Carter still believes in the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force.

Yes, I do. As you know, after quite a bit of argument and debate, this principle was included in the Camp David agreement.

Is there anything you would have done differently in the Iranian hostage crisis?

I can’t think of anything that I could have done differently, and I haven’t seen anything in the analyses by any others that suggested any practical ways of dealing with the situation differently.

You know, this was one of the most difficult periods of my life; and even in retrospect, under the circumstances that then prevailed, I don’t know of anything that I could have done differently. (Laughing) Knowing now what I did not know then, I would have had another hydraulic system available in our number-six helicopter, or sent another helicopter, but that was an unforeseeable development. I wanted to preserve the lives of the hostages and protect our nation’s honor, and I was finally successful in doing both.

As of the time of this writing, President Jimmy Carter has been in failing health for some time, and things look grim. History may treat his legacy with much more kindness than he received during the years following his Presidency. Suffice it to say that the world changed dramatically under the Reagan Administration theory of economics, and we’ll leave it at that for now. Should you make it to Atlanta, you might be surprised at the Presidential Library, actually. Then of course you need to have a peach margarita at the Sun Dial in Peachtree Plaza, which will probably not surprise you at all.