Why is Paul Newman Mad As Hell And Not Going To Take It Anymore?

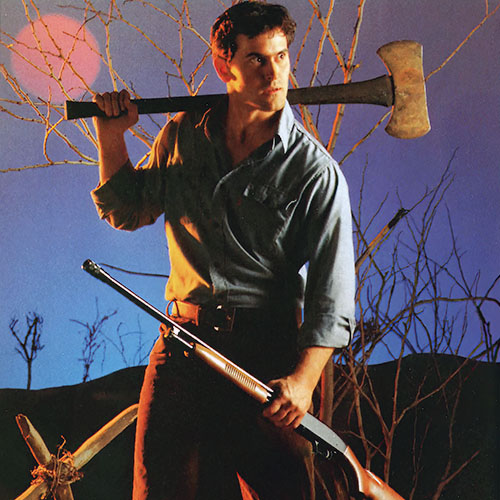

Newspaper Man: Paul Newman

The controversial film Absence of Malice has provoked a national debate on the rights and responsibilities of the press. In this exclusive Penthouse symposium, Paul Newman joins with director Sydney Pollack and screenwriter Kurt Luedtke to explore these vital issues.

For generations of journalists, the movie house has always been a place of refuge, a haven in a heartless world. Politicians rail at our lack of patriotism — “Whose side are you guys on?” Secretary of State Dean Rusk used to ask during the Vietnam fire storm — advertising salesmen gnash their teeth when a paper or television news program goes after a major advertiser, demagogic moralists accuse the media of a godless attack on traditional ethics. But from Deadline, U.S.A. to All the President’s Men, movies have almost always shown the reporter risking life and limb to uncover crime and corruption, protect widows and orphans, and preserve the Constitution itself.

So it’s an instructive experience to sit in a packed theater on the cosmopolitan, trendy-liberal East Side of Manhattan and listen to an audience cheering a quietly merciless evisceration of journalism in the film Absence of Malice. It is equally instructive — not to mention amusing — to listen to reporters and broadcasters reacting to the film as if Hollywood had suddenly decided to take a Zippo lighter to the First Amendment.

A spate of newspaper and magazine articles have attacked the premise that any veteran investigative reporter would commit the misdeeds depicted in this film: writing up a confidential (and spurious) government file without checking the facts, printing a story that drives a troubled woman to suicide, then wrecking one’s own career by “exposing” a payoff that never took place — that was, in fact, fabricated by a press victim for the purpose of making federal prosecutors and the press look like fools.

Journalists, wrote the New York Times’s Jonathan Friendly, “doubt that any self-respecting paper would long tolerate, much less encourage, the kind of naivete of the reporter, much less the deliberate sensation-seeking of the editor.” According to the New York Daily News’s Marcia Kramer, “If Sally Field had spent a week with me … she would have balked at portraying a character so naive.” Pulitzer Prize — winning reporter Lucinda Franks added that the journalists “seem half the time as grossly distorted as if seen in a funhouse mirror …. In real life [the Sally Field character] never would have made it as an investigative reporter in the first place.”

Some of this outrage simply demonstrates that reporters are as susceptible to thin-skinned defensiveness as any other professionals. I didn’t notice an outburst of indignation at the treatment of health professionals in Paddy Chayevsky’s Hospital, or at the portrayal of network TV executives in Network, or at the view of nursing-home operators on a famous “Lou Grant” episode. Nor is it possible to view the film as terribly unfair in the light of real-life malfeasance on the part of the fourth estate:

- Would a great newspaper print facts without checking? The Washington Post’s “Pulitzer Prize” story about a non-existent eight-year-old heroin addict was far worse a wrong than anything depicted in Absence of Malice, as was its gossip column’s account of the bugging of Ronald Reagan’s Washington guest quarters at the hands of the family of Jimmy Carter.

- Would a reporter run a story knowing that its publication might make the person who is its subject take drastic, even fatal action? A New York Times reporter ran a story about the Jewish heritage of an American Nazi leader after being told that the leader might take his own life. After the report appeared, the subject committed suicide.

- Would a reporter sleep with a source about whom she wrote? A Philadelphia Inquirer reporter did just that.

- Would journalists permit themselves to be “used” by prosecution-hungry government officials? From the days of Joe McCarthy to Watergate and Abscam, and from Washington to DA offices around the country, such reporting has been, and still is, commonplace.

More significant, however, is the point that journalists seem utterly unable to grasp. We who report and write for a living seem to regard what we do as a public service; we’re the “good guys,” protecting victims from wrongdoing at the hands of the “big shots.” We expose corruption, political double-dealing, consumer rip-offs, to fulfill that classic definition of journalism· to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” And a lot of powerful, unsavory people, from mean streets to corporate suites, don’t like the press because it often does this job well.

But the fact is, a lot of ordinary, honest, hardworking Americans don’t see the press this way. To them “the media” have become just another one of the big shots — wealthy, powerful, capable of doing great harm, and absolutely unaccountable to anyone for what they do. To wit:

- A DA or a cop still needs a warrant to bug a telephone or stake out a suspect. A reporter and a camera crew can hide microphones and cameras with no authority except the conviction that somebody may be doing something wrong.

- A police officer can’t stop someone on the street without “probable cause,” a standard that has to hold up in court. A journalist can chase a citizen down the street, cameras rolling, and paint a picture of guilt that no explanation can eradicate.

- A prosecutor can’t quote evidence in a trial without a defense lawyer’s demanding that an entire conversation be presented to a jury. A top-rated news show can edit a two-hour interview into a one-minute sound bite without ever putting a damaging remark into context.

“But we’re not the police!” investigative journalists reply. True: but in our mass-media society, the power to expose can often be far more devastating than the power to investigate and even to indict. Such prominent Americans as John Connally, Maurice Stans, and others have resumed a place in the councils of power after winning jury acquittals on criminal charges. But who recovers from page-one, prime-time charges, aired with no institutional protections whatsoever? As Paul Newman bitterly remarks, after a phony news story has smeared his reputation and destroyed his business, “You say somebody’s guilty, people believe it. You say they’re not guilty, nobody’s interested.”

Some journalists see Absence of Malice as a dangerous film, coming at a time when the public seems willing to punish the press with enormous libel verdicts for factual errors of minimally damaging effect (the Carol Burnett case against the National Enquirer), or even when satirical, clearly fictional accounts appear in controversial publications (the Miss Wyoming case against Penthouse). Others warn that, at a time when Congress and the administration seem determined to impose criminal sanctions against a vigorous investigative press, this film will damage the cause of the First Amendment. A Village Voice critic called the film “a timely backlash movie [which] feeds on and fuels the burgeoning suspicion of the press.”

It’s a curious notion, considering how often the press has rejected — rightly — appeals from the government not to print embarrassing stories that might harm “the national interest.” But this reaction to the film also fails to note how deeply millions of Americans have come to fear and mistrust the press: not because it’s too liberal or run by Eastern Jewish elitists but because it’s gotten too arrogant, too self-righteous, and too indifferent to the real questions about ethics and standards that this film raises.

Of course government censorship or regulation is wrong. The question is: how to build an ever fragile consensus behind the values of the First Amendment. In a major survey taken for the Public Agenda Foundation in 1980 by Daniel Yankelovich, the pollster found “a serious disagreement between leader and the public” about the purpose of freedom of expression.

Media leaders, he said, see freedom as a good in itself. But “in the public’s view, the primary objective of freedom of expression in the media is a fair, balanced presentation of all points of view …. If leaders do not acknowledge the legitimacy of the public’s concern, they can hardly expect the public to rally to the support of principles” of free expression.

A good place to start thinking about these concerns would be to make Absence of Malice required viewing in the newsrooms of America. — Jeff Greenfield, commentator for CBS News and syndicated columnist.

Paul Newman, Sydney Pollack, and Kurt Luedtke spoke individually with Penthouse contributing editor Bob Spitz, who edited their comments into the following symposium.

As a film, Absence of Malice attempts to confront the tensions that seem to exist today between private citizens and the press. What actually motivated you to make a film like this?

Paul Newman: There are acute inaccuracies and abusive journalism running rampant today, and perhaps something will be done about it — although I’m not sure what can be done.

What kind of a job is the press doing, in your estimation?

Kurt Luedtke: By and large, I really have to say that I think the American press does a very good job. But the notion that it’s infallible, or perfect, or should not be the subject of criticism or scrutiny, is ridiculous. The popular notion that we’re really infallible and perfect and always on the public’s side just ain’t so.

Sydney Pollack: There is something that we all believe from our childhood: that is, if it’s in print, it’s true. Everything that’s in print is chiseled in stone: “Look, so-and-so’s doing such-and-such; it says right here in Time magazine.’’ I did feel that it was worth taking a hard look at — not the evils of the press as much as the difficulties of monitoring truth on a twenty-four-hour-a-day basis.

Newman: I really believe that if certain papers have nothing happening, they infuse rumors into a piece and try to stir something up. They’re expected to come up with something sensational every night of the week to keep their readers’ noses buried in the pages, and, well, you tell me … if nothing’s happening, what do you do? Well, in their case, they make it up.

If I were a journalist, my primary concern would be that people believe what I write. That’d be all that matters. But today they’re all scrambling for the big event, the big story. Reporters make a name for themselves at our — the people’s — expense.

Pollack: I think there’s been a shift in the emphasis of the press since Watergate, a kind of post-Watergate morality. A greater sense of urgency to break stories that expose rather than explain. The fact of Watergate, the fact of the Pentagon Papers and things like that, have created a kind of drive in young reporters specifically to find and uncover something behind every rock. Journalism has become less explanatory than predatory. The search for wrongdoing and perhaps for Pulitzers has become almost obsessive since Watergate.

Luedtke: I can’t say that I’ve ever honestly seen a situation where I was aware that someone was damaged because a journalist was after a prize. I think all good newspaper people are after the big story. It’s in their bones, and they know a good story when they smell one.

I sometimes think that, out of all the people who should realize how complex the world is, it should be the press. And yet sometimes I think the press is the last to realize that it’s very, very difficult to compress truth into eighteen paragraphs. Every senior newspaper editor in America will tell you what Abe Raskin was saying fifteen years ago, which is that every time he is himself directly involved in an event or proceeding that winds up being reported, he’s amazed at how little the press manages to get right.

“I would say that ninety percent of what people read about me in the newspaper is untrue … Ninety percent garbage!”

How much coverage of a celebrity’s life that finds its way into print is accurate?

Newman: I would say — conservatively — that ninety percent of what people read about me in the newspaper is untrue, completely fabricated, or altered in some way. Ninety percent garbage.

Have you ever tried going after a paper that printed lies about you or your family?

Newman: The rule of thumb is: it’s not worth it.

But what about Carol Burnett’s case against the Enquirer? Last year she sued them for libel and won a fairly large settlement, the first celebrity to emerge victorious against them. Doesn’t that give you some kind of incentive to sue?

Newman: Yes, but she had a way of proving — of measuring — the damage inflicted upon her. She was actively working with alcoholism groups, and that gave her case credibility. That’s essential to establishing a case. It was a way of measuring the effect that a story like that had on her life.

But what do I do? Go in front of a judge and say, “I’ve had terrible back pains ever since I read this article?” Or, “I had terrible emotional distress. I cried all night long.” I wouldn’t have a prayer! So it really doesn’t matter how nasty they get about your personal life. I’m helpless in matters like those and have learned not to let things like that bother me. [He pauses reflectively.] Aw, that’s not true, either. They rile the hell out of me! They do. I just have to grin and bear it, because that’s the kind of protection we “public figures” get from the press.

The First Amendment, as it has been interpreted by the courts, generally guarantees most citizens their right of privacy. “Personalities,” stars, famous people, however, must prove malice — not just negligence — to win a libel decision. Where do you draw the line between private citizens and public figures?

Luedtke: The argument is this: that if you choose to make your living in the public eye, you have voluntarily made yourself a public figure. Given the current state of libel law, what that apparently means is that, by choosing to make a living in the public eye, you have agreed in advance to tolerate innuendo, inaccuracy, and speculation. You have agreed to tolerate absolute falsehood unless you can show reckless disregard. I don’t feel very comfortable with that. I think we ought to have a little leeway with someone like Paul Newman, but I don’t think it ought to go to the extent of absolute inaccuracy, where no public good for printing material other than false interest can be shown.

The federal interpretation of the First Amendment dictates that if you’re a “public figure,” you’ve elected at your own free will to make yourself the object of speculation. How do you feel about that as it relates to your life and your career?

Newman: I think the laws governing that are much too easy in this country. We’ve got to be a lot more careful what we say in print about people, or we can do incredible emotional damage. I’ve been in situations where people I know are getting a divorce. I’ve gone to their house to play Ping-Pong, and all of a sudden I’m the guy who broke up their marriage. That kind of stuff’s printed all the time about me.

Pollack: Look at Jean Seberg. The FBI leaked a story that found its way into Joyce Haber’s column, about Jean’s having a child illegitimately with a Black Panther. That so affected Jean Seberg that when the baby died, she put the baby in a glass-topped coffin and flew it back to Marshalltown, Iowa, her hometown, and stood there so that the people who came to the funeral could in fact see that the baby was white — and, therefore, the child of her husband, Romain Gary, and not an illegitimate child by a Black Panther.

People seem to thrive on stories like that.

Newman: You bet. Now, I don’t know what percentage of people this applies to, but it must be a growing percentage, because if you read newspapers, story after story is utter garbage, nonsense like that. Yet people read them, although they must know they’re not true. Newspapers may be picking up short-term circulation, but they’re cutting their throats in the long run. When fifty percent of the people don’t believe what they read in the newspaper, then maybe editors will learn. But who knows? What will be the tragedy of that? You figure people won’t buy them, but they still have to figure out what’s on sale at Macy’s. But that’s all papers will become — advertisements — because no one will have any faith in the type of stories they print.

But, on the other hand, there are papers and magazines that would argue that the public honestly enjoys this brand of gossip/entertainment-as-news type of reporting.

Luedtke: But the public isn’t running the newspapers. If the rule is simply to supply what it is the public will thrive on, then we’ve got a lot of radical changes to make at a lot of newspapers. If that’s the benchmark, then some pretty terrible material is going to result from that.

Newman: With all those murders and rapes and gory situations that make the front page, I guess there are plenty of people who want to read about it. I know those people are going to get off on stories like that. I think that, in the final analysis, they don’t give a damn about the news. They just want to be entertained.

All I know is that reporting, of late, is ludicrous. I turned on the six o’clock news the other day, and first they reported two grisly murders — that was their big lead. In third place was the replacement of the premier of Poland, followed by the burial of Moshe Dayan. That’s the order of priorities. Do you believe that shit? TV broadcasts in a sensational vein. Their news is for the lowest common denominator. Television can do that … well, we’re in a lot of trouble.

Even someone as prominent as Jimmy Carter was not immune from a paper like the Washington Post, whose story that he and Rosalyn had the Reagan’s Blair House apartment bugged was hardly factual. Do you think they should have printed the rumor in the first place?

Luedtke: That’s stretching the definition of news too far. I agree it’s probably true that the Post was correct, in that it was being whispered about in some small circle that the Carters were part of the bugging of Blair House. But that is much too fragile a truth to stand on when you know full well that it’s not going to be read in exactly the way it was intended. You’re effectively disseminating a rumor, and if the rumor were of a sufficient size and magnitude and enough people were involved that you really were dealing with a bona fide news event — and rumor can sometimes be a news event — that would be one thing. But when you are dealing with something that you believe not to be true, that’s simply being gossiped about, then I think it should not be printed.

“I don’t believe journalists should have to identify their sources, or we’re going to stop the source of 80 percent of the hard-news coverage we get.”

Newman: It would be interesting if Carter took it to court, wouldn’t it? They said it was a rumor. They didn’t say it was a fact. A little nifty doubletalk, if I do say so. But I’m the victim of this kind of stuff all the time, and I wish to hell there was something that could be done to prevent it. But since I’m someone who makes movies, who entertains people, I have to allow un-truths to be printed, not just about me but about my family as well. It’s really not very fair.

Do you have any suggestions that might be put forth to prevent this kind of a situation?

Newman: I’m not sure. That would have to be left up to much better and stronger minds than mine. But something has to be done … something that corrects items in papers like the New York Post.

After Fort Apache, I went out of my way to mention the New York Post as a garbage newspaper. It simply invented captions to go with certain photographs of me, telling stories that didn’t exist. This was in relationship to a sense of turmoil they wanted to create around a picture that was about the South Bronx — and it simply didn’t exist. I mean, they invented riots where there were no riots. They invented them — not blew them out of proportion, as they would like people to believe. They simply invented situations. Now, I guess what they wanted to do was to create a sense of turmoil where there wasn’t any story, just to aggravate things.

They took a picture, when we were three or four days into production, where a girl production assistant was just going over to one of their photographers, just on her way to rehearsal, walking to the set, and when that picture appeared, the caption beneath it said, “Paul Newman gasps in horror as production assistant wards off protesters.” There weren’t any protesters! There wasn’t any situation. That was made up.

And there wasn’t anything you could do to prevent it? Or any action you could take against the newspaper?

Newman: Like what? What grounds would you suggest I have? I’m not hurt in any way, nor was I libeled. I held a press conference to point out to these newspapers that certain situations falsely reported did not, in fact, exist. I told them it was not a racist picture and that people were taking things out of context, just misconstruing everything. During the course of it, I mentioned that particular situation. And after it was over, I went down to where the cameras were and talked to some guys from the Amsterdam News, and when the New York Post reported it — the press conference — they said, “It was broken up when the protesters stormed the hill.” I couldn’t fucking believe it! There were a couple of people down in the streets with pamphlets, but all they were doing was handing them out peacefully.

Absence of Malice presents a somewhat contemptuous view of the press. Its theme is that an essentially honest and professional reporter can still be manipulated — and duped — by government agencies wishing to disseminate rumors. Do you feel that’s the case across America today?

Pollack: I believe that it can and does happen. I don’t necessarily believe that’s an indictment of the press as much as it is an indictment of the process. We’re dealing with a process here. Newspapers are particularly vulnerable, and so are the television media, to outside manipulation. From law-enforcement agencies, from political agencies you read, “Sources close to the president said …” or “Sources in the White House said …” Sources, sources, sources! Who are all these people?

Anybody in the world can say anything they want about another person in this society and be assured of more protection than the person who’s the object of this story. That’s one helluva volatile situation to have to deal with.

Then you personally feel that there is a gross injustice in the manner by which sources are protected — that journalists should be able to both protect and identify their sources? How is something like that to be satisfactorily achieved?

Pollack: I don’t believe journalists should have to identify their sources, or we’re going to stop the source of 80 percent of the hard-news coverage we get. But I do believe that it becomes incumbent on the part of the reporter to be doubly careful about the accuracy of those leaks. Doubly, triply careful. Also to weigh what the consequences are to everybody involved. How much need-to-know is there? You have to weigh that. If it’s the Pentagon Papers, I would certainly agree with the New York Times — we do have a right and a need to know. I applaud their decision to go ahead and print it. I’m not so sure, for example, about the Burros case.

Burros was a guy who was a member of the American Nazi party. It was discovered by a leak, to the New York Times, that Burros was also a Jew. A reporter from the New York Times went to interview Burros and confronted him with this fact. And Burros, in effect, said to him, “If you print that story, I’ll be ruined. Everything I’m about will destroy me. You’ll destroy everything.”

The reporter received another phone call from Burros just before he printed the story, saying, “If I go out, I’m going to go out in a blaze of glory.” Anybody listening would have known that he was talking about suicide. The story was printed, and Burros shot himself, put a bullet through his head. I’m not so sure what was achieved. I’m not certain I’m for or against … but I’m saying it’s worth a lot of serious thought.

There are things reported all the time in which one can question the degree of need-to-know.

Luedtke: I remember a terrific situation in which a candidate, who happened to be black and who happened to be a criminal lawyer, was running for public office in Detroit. An individual who was a former FBI agent called and said that he understood that the newspaper was looking into the background of this candidate, and he wanted us to know that our continued inquiry might well jeopardize a federal investigation. That, I might add, is a real cute stunt. He wanted to persuade us that, indeed, something was there, and he couldn’t have done a better job. We didn’t get suckered by that. But I hate to think about the times we have been and still don’t know about it.

So, in effect, you feel that government agencies and politicians attempt to use the press to promote their own best interests?

Pollack: Well, that’s a part of it, I think. You know, innumerable times when newsmen needed desperately to get inside a story, a member of the FBI would “discreetly” oblige, leaving them alone with internal FBI files. City papers, in highly competitive situations, and wire services literally scrambled for favors from the FBI. They followed every new lead from official sources and raced to the phones with every revision to the Ten Most Wanted list. They were being manipulated — which is part of what the picture is trying to get at.

Were you ever in the position where you regretted having printed something about a person who got hurt over the piece’s appearance?

“The press on its own ground is very powerful. We do own the printing presses, we do own the televisions, we’re very hard to push around.”

Luedtke: Absolutely. Many times. My paper printed a story about a ranking Detroit police official being under investigation. And, indeed, he really was under investigation. As a result of which he lost his job, and his ability to get another job was severely damaged. And nothing came of the investigation.

Did you print a retraction to that order?

Luedtke: Well, we couldn’t retract, because what we printed was true: he was under investigation. Whether or not there was ever any reason for him to be under investigation is a very different story. We were able to work out a situation where, through a very conscientious U.S. attorney, the unusual step of formally announcing the end to an investigation took place — and saying, formally, that there was no reason to proceed further, that there was no reason to think that this individual had committed a criminal act. In the meantime, his police career is over. He now has a job, but it’s quite clear to me that the news stories affected that man’s life.

Then you’re asking for some sort of uniform — perhaps federal — restriction on the press?

Luedtke: Absolutely not.

Pollack: The only thing I can say as a layman — as an outsider — is that the selection process of who is or isn’t allowed the responsibility of reporting a major event has to be a tougher selection process, because we are finally and ultimately at the mercy of the individual who’s doing it. And I don’t see any way we’re going to change that rule. Government legislation would just be a form of censorship and absolutely unacceptable. If I thought a newspaper should be censored, then I’d certainly have to advocate the censorship of film. Then books. And I don’t advocate that at all. I think that would be a disaster.

All of this comes at a time when the Reagan administration is trying to roll back the Freedom of Information Act, which grants access to heretofore confidential files the government may have about us. Don’t you find that a bit disconcerting?

Luedtke: People make much of the Freedom of Information Act, but the fact is it’s only fifteen years old. The republic got along fine for more than 150 years without it. It only makes information easier to get; it does not make the information readily available. Reporting is frequently hard work and frequently should be. It seems to me that what we care about in the First Amendment is the right to publish. And I don’t think we can tamper with the right to publish without doing much greater damage.

Pollack: Here is my hope — and I’m being an idealist. My hope is that a picture like Absence of Malice — that the best possible thing I could hope for is that it would have the effect of jolting the press people into the realization that if they don’t do something about it themselves, then a combination of public opinion and the present administration could eventually press for some kind of legislative action. And I think that would be a disaster.

Luedtke: I think it’s always possible that people in the press can say, “Gee, I wish they hadn’t made that movie. People are not very happy with us already, and this (movie) is going to add fuel to the fire.”

That’s a valid point. How would you answer that?

Luedtke: The press on its own ground is very powerful, very capable of taking care of itself. We do own the printing presses, we do own the televisions, we’re very hard to push around. If we are confining the First Amendment question, the freedom-of-the-press question, to the right to publish, it would take something that would require at least a little help from God to do much to set us back.

The place it might show up — in some people’s eyes, a detriment to the press — would be in the expansion area, to get still more room for the press. You’ve got some people now who insist upon making access a First Amendment question, who contend that, for instance, reporters should not have to testify for grand juries. These people will probably think, perhaps with justification, that this movie would be a tall setback to us. They’re talking about a right that I don’t think they should have anyway, so I wind up being not terribly bothered by it. I’m particularly not worried about — what people seem to keep asking — is, Isn’t the press in great danger from the administration?

I would think that’s a rather valid question.

Luedtke: And I think it’s absolute nonsense. If the American press is susceptible to being done in by a singular administration, it would have happened 200 years ago. There are a great many administrations that would have liked to have stuck it to the press. If we’re no more powerful than that, then apparently society is safe from us and no one should worry about us.

Absence of Malice portrays a situation in which a reporter, played by Sally Field, allows herself to be manipulated not only by a government agency but, later, by her emotional involvement with a chief suspect in an investigation, played by Paul Newman. People are going to be somewhat disturbed that the reporter in the picture is a woman, and in effect it says to them that women, although highly professional, are susceptible to intense emotions and subsequently cannot be trusted.

Luedtke: To the extent that that may be a reaction, of course I regret it. I personally would have preferred that the reporter involved be male. The structural problem that we had with that … we did want at least something of a love affair in there. So, to reverse it, we would have had to conjure up the notion of a female murder suspect tied to the Mafia, which I think strains the credibility.

And yet, remembering the example of Laura Foreman, in Philadelphia, a reporter who admitted being tied romantically to and accepting gifts from her major suspect, there indeed seems to be a problem that reflects this very notion. A woman can become more emotionally attached.

Pollack: I think a lot of that goes on sexually both ways. Some editors have said: “I wouldn’t have any reporter like that working for me!” I think that happens to be bullshit. Many of them may believe what they are saying, but a lot of people who have made that comment have reporters like that working for them, and I can document it.

Is there anything you might want to say about the character Mike Gallagher and the way he was able to compromise the reporter who stalked him in the movie?

Newman: Sure — he thought Sally Field was great in bed. God, there were no words to describe that one-night stand!

But Gallagher was just setting her up for later on, when he turns the tables on her. Isn’t that right?

Newman: No way. That was real all the way. A stiff prick has no conscience. [He roars with laughter.] It’s true, though, isn’t it?

Well, it doesn’t bode well. In fact, the movie seems to present the hypothesis that women reporters are too emotional to be trusted with their work.

Newman: Yes, well, I think that’s unfortunate. It looks like, “Fuck her, drop her right in the sack.” So I think feminists will take that viewpoint, that we show they’re the weaker sex, and well — good, good. People’ll have a lot to talk about. But you know as well as I do that wasn’t Sydney’s intention. He merely wanted to create a love story, and that was the way it had to be.

But what do you think it says — or rather. how do you feel about a woman’s emotional stake in reporting a story accurately? Do you think that she’s too susceptible to a romantic entanglement?

Newman: [A lot of laughter.] I think both sexes would like to get their news in bed. I would. But as far as the norm goes, I think most professional journalists go by the book and keep their emotions at home. Let’s face it: you can spot the stories that were gotten by a piece of ass.

Should you develop a wild hair to watch Absence of Malice suddenly — a hair that went wild around here, certainly — the last 40 years have brought us some wonderful options.Granted, it will cost you somewhere between $3 and $14 to watch it (as of this report), but popcorn at the movie can cost that much, and you’ll get a chance to see what movies were like when the actors had to work with dialogue instead of computer generated graphics in order to get the theme across. It was a different time, for sure, and yet this story still sounds familiar.