The author of “Shogun” and “Noble House” warns: “Nobody looks at history; nobody knows anything about the past. … We are under siege economically. And historically, all wars have started for economic reasons.”

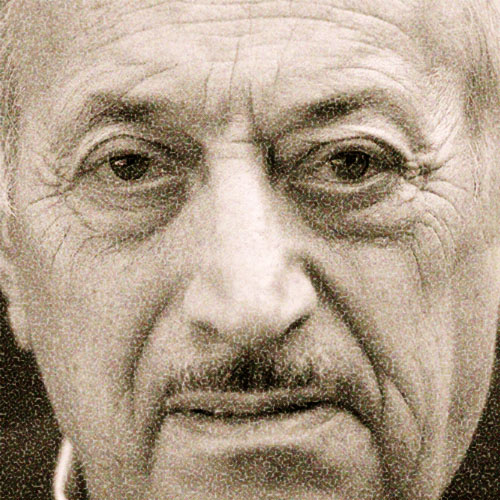

James Clavell (and Asian Culture)

For nearly 20 years, James Clavell has been writing best-selling novels set in Asia. First there was King Rat, the story of his three years as a Japanese prisoner of war. Then came Tai-Pan, an epic novel about the founding of the great trading colony of Hong Kong. Then came Shogun, the adventures of an English seaman in medieval Japan. Now he is riding high on the charts with his latest work, Noble House, a mountainous volume of 1,200 pages of business intrigues, murder, romance, espionage, family feuds, smuggling, and even a few natural disasters, all in the Hong Kong of the early 1960s.

Clavell calls the four books his “Asian saga,” and he promises there is more to come. The next novel, Nippon, is to be set in Japan, and then, perhaps, he says, he will deal with modern China. “The idea,” Clavell told Penthouse interviewer Joseph B. Treaster, “is to tell in fictional terms the history of Anglo-Saxon involvement in Asia from the beginning to the present day.”

Some critics have jabbed at Clavell for delivering “sugar-coated history” lessons, but Asian scholars are beginning to recognize that his work is having an enormous impact. More than 8 million copies of Shogun have been sold, and an audience estimated at 130 million watched a 12-hour television presentation of the novel last fall. “In sheer quantity, Shogun has probably conveyed more information about Japan to more people than all the other combined writings of scholars, journalists, and novelists since the Pacific war,” according to a group of professors in the Asian studies program at the University of California at Santa Barbara. The university men, who have produced a booklet entitled “Learning from Shogun,” say that as many as half of the students enrolling in college courses on Japan these days have read Shogun and that many apparently became interested in the country because of the book.

In a departure from his work on Asia, Clavell last month published a slim volume called The Children’s Story, an apocryphal tale set in a second-grade classroom. His daughter, then six, had just learned the Pledge of Allegiance. He asked her what it meant. She did not know. Neither did most of the adults Clavell later asked, and he sat down to write the little book. “What is freedom?” he pondered. “And why is it so hard to explain?”

James Clavell, 56 years old, has traveled frequently to the Orient in the last four decades and has become an expert on Asia, with strong views on the region and its relationship to the United States and the rest of the world. He is a naturalized American citizen.

Clavell came to the United States from England in the early 1950s with dreams of becoming a film director. He was well on his way to a successful career in Hollywood before he turned to writing novels. He might never have done so, in fact, had it not been for a screenwriters’ strike and the prodding of his wife, April, a former actress and ballerina. He also might never have become such a successful novelist had it not been for a New York editor named Herman Gollob. The manuscript for King Rat, which Clavell had written in 12 weeks, was gathering dust on a desk at Little, Brown & Company when Gollob discovered it. He took the book home over a weekend, liked it, and persuaded his superiors to let him work on it.

“Herman showed me, in effect, how to write a novel,” Clavell says. “At least, that’s how he tells it. We spent two and a half months rewriting. When I first saw the manuscript he had edited, it had only one line left on the first page.”

After King Rat, Clavell returned to films. He had become the complete movie man: writer, director, producer, the commander in chief, and he was having a great time. But he was annoyed, too. He wanted to be thought of as an author. “There were a lot of rude buggers around,” he says, “who were saying things like ‘Sure, you wrote one book. But can you do it again?’”

So he went to Hong Kong, then came back and wrote Tai-Pan.

Almost as Tai-Pan was coming off the presses in 1966, To Sir with Love, starring Sidney Poitier, was released. To Sir was one of a half-dozen films that Clavell wrote, directed, and produced and was probably his greatest achievement in Hollywood. His first screenplay, for The Fly, has become something of a classic in science fiction. Another of his screenplays was The Great Escape, a film that featured Steve McQueen.

Clavell, tall, sturdily built, with sandy gray hair and pale blue eyes, comes from a family line of military men dating back to 1067, and he likes to think of himself as the English equivalent of a samurai. Shortly before he was born on October 10, 1924, his father, Capt. Richard Clavell of His Majesty’s Royal Navy, went out to Australia to help establish the Australian navy. His mother went along. James was delivered in Sydney, christened in the upturned bell of the battleship, H.M.S. Melbourne, and bid a happy life with a song by Dame Nellie Melba.

After nine months the family returned to England. His childhood, Clavell says, was “very disciplined. I was going to be an officer; therefore I called my father ‘Sir,’ and therefore he did certain things to train me. People say, ‘Well, how can you be writer-producer-director?’ and I say, ‘Well, you see, if I wasn’t doing this, I’d stand on the quarterdeck of a ship and I could rule the ship.’ I’m not saying that pompously or arrogantly but only because my training was to do that.”

As a boy, Clavell attended a private military school. When England went to war, he was 16. He went into the ranks for three months, then became an artillery officer. His unit had been designated to go to the desert of North Africa. Instead it was shipped to steamy Singapore. In March 1942 the British and Australian troops there were overwhelmed by the Japanese. Clavell, then 18, caught in Indonesia, slipped into the jungle, persuaded a village headman to give him shelter, taught himself the Malay language, and lived like a native for six months until the Japanese discovered him. For the next three years he was a prisoner of war, two of the three years in the Changi prison in Singapore, where only 1 out of 15 men survived. These adventures became his semi-autobiographical King Rat.

Clavell would have gone on with a military life at war’s end, but his left leg was smashed in an accident (“One story I like to tell,” he says, “is that I had a motorcycle crash”), and he was mustered out of the service on a medical disability. He tried studying at’ Birmingham University for part of a year, but that only proved frustrating. “I didn’t know what the hell to do,” he recalls. The woman he was dating at the time — the actress and ballerina who eventually became his wife — took him around to a film studio. “I saw what a director did,” Clavell says, “and I thought, ‘This is for me.’” It wasn’t long, he says, before he recognized that “if I wanted to be involved in films, I should move to Hollywood.”

By now, James Clavell is a wealthy man. He lives most of the time in an elegant home, filled with Oriental art, in the Bel Air section of Los Angeles. But he drives a five-year-old TransAm, dresses simply in navy blazers and gray slacks, and often flies economy class. He has an occasional drink, puffs on a cigarette — but does not inhale — perhaps once a week, pilots a rented helicopter to relax. He is not much of a socializer. On a typical Saturday night with his wife, he says, “we probably have eggs and bacon, and we might watch some television or read a book.” Most of the time he is writing. It doesn’t matter where he is. A glazed look comes over his face, and he is gone.

What would you say are the major differences between Asians and Americans?

We are such an impatient people. Asian people understand patience, because they’ve had to for so many centuries. Unlike Asians, American people and American politicians have no understanding of history or concern with it. Asian people love negotiation, and they are concerned with “face”— form of manners. They like diplomacy and care about the nuances of diplomacy. Americans are people of all nations that have grouped together with one common language. The key to America really is our language — it’s the reason we are a cohesive whole. We can communicate with each other. Americans have taken this country and made it an absolute Boomsville. But you can’t implant Americana on China or Japan, because the attitudes toward life are totally different. We couldn’t impose our form of government on the Chinese. I believe that their government at the moment suits the majority; otherwise, it wouldn’t exist. I truly believe that.

Why has communism been able to sweep across the whole of mainland China?

There are only around 16 million Communist party members amongst almost a billion Chinese. The party has the power. You must remember that Chinese people in all their glory are Chinese first and Communists, or whatever, second. Many Chinese on the mainland were not satisfied with Chiang Kai-shek’s approach. Mao Tse-tung and his armies never looted; they paid for what they wanted, and they never stole crops. If you look at their 4,500 years of history, the Chinese have always been suspicious of police and suspicious of government because, historically, eventually, the government has not been good for them. That is why they concentrate so much on family, their own particular families and their own particular villages. They’re not concerned with central government. And although the Communist system is implanted on China now, if the Chinese people as a group did not want it, it would not exist. In other words, they can live under the Communist system provided the system doesn’t bother them too much.

But why would the Chinese choose communism?

Well, it’s not a question of their choosing it. If you look at any “new” dynasty, you’ll see that the first ruler sat on the Dragon Throne with blood on his hands. Right? Even so, the Chinese believe that once the emperor loses the mandate of heaven, it is the duty of the people to revolt.

So, according to the Chinese, Chiang Kai-shek lost the mandate of heaven?

Yes. He fell from grace because he was beaten. Chinese say you must always get behind the emperor when the emperor gets to the throne. Normally you give him your allegiance. Chairman Mao and his people took full control of the armies of the China mainland, and he proclaimed it the People’s Republic of China. He became, in effect, emperor.

The Chinese who went to Taiwan have a different view. They believe that Chiang Kai-shek was the best form of government for China at the time that he ruled. Then the armies led by Mao were victorious. The Chinese people followed the victor. It’s like in the American Civil War: Grant was the winner, and Lee was the loser, and that was that. But don’t forget: Chiang Kaishek and Mao Tse-tung both agreed Taiwan is Chinese territory.

Do you see China expanding its Communist influence?

No, absolutely not. Historically, China has never been hegemonistic.

But they invaded Vietnam a short time ago.

Well, they will always do that when a barbarian or non-Chinese army approaches their borders. They always have. They always will.

And they took Tibet.

Yes, because according to them that’s in their sphere of influence. They never go beyond what they consider to be their historic borders. For example, they went into India in 1962, but just to the point that they claimed to be their border; then they withdrew. It’s my absolute conviction that Chinese involvement in the Korean War was unnecessary. Historically, the Chinese have always poured over their borders to attack a barbarian when he approached, whether through Vietnam or through Korea.

If China had really wanted to go into Vietnam, it could have done it. In 1962-63 there were 116 million people of military age in China, so now that figure has probably doubled. If China had really wanted to go into Vietnam, it could have opened the borders and said: “Okay, now, please resign or else we’re going to trample you to death.”

So why did we have the Chinese against us in the Korean War?

Because Americans don’t look at history. If we looked at history, the history would explain the present and the present would foretell the future. For example: four times in history, China has gone over the border across the Yalu River when an alien army has approached its border. So it’s pretty axiomatic that if we Americans approach the Yalu River, as we did during the Korean War, then the Chinese will come over the border. MacArthur made the mistake. Supposedly, he was a historian, but he absolutely didn’t read Sun-tzu, and he absolutely didn’t understand anything about Chinese history. Because after he’d gotten over the Thirty-ninth Parallel, he should have discreetly — not in front of television cameras with flags waving — sent a letter to Prime Minister Chou En-lai and said, “Look, please, we have these thugs in the northern part of Korea who are really upsetting us. You know that they are mostly Soviet oriented and sponsored, which we all agree is not good. Do you mind, please, if we get rid of them? Or would you assist us in getting rid of them? We won’t go any further. We understand your policy on your borders, and please excuse us for coming here, but these guys are criminals.” That would have given everybody a face-saving formula for avoiding war. I’m absolutely certain that Chou En-lai, who was one of the great pragmatists of recent times, would then have found a solution to settle this business.

We would have had a smaller conflict in Korea?

We wouldn’t have had any conflict with China, because China doesn’t want to get into conflicts. It has enough problems. The Chinese people are good citizens. They work hard, and they’ve got 1 billion people to feed and try to police. And I believe they had never and would never break out of their borders unprovoked.

Where do you think we went wrong in Vietnam?

If I could answer that, I would shout it from the rooftops. But I’m a story-teller, right?

All I can say about Vietnam is, read history. Read what’s happened in Vietnam for a thousand years: their attitude toward the Chinese, the Chinese attitude toward them. I think certain people chose wrongly — they chose for a confrontation.

You mean the Americans chose for a confrontation.

Yes. Somebody decided to have a confrontation and to confront guerrillas in a jungle. The people who chose Vietnam knew nothing about Vietnam. They’d never been to Vietnam. We should ask the Pentagon: “Who actually decided? What generals? Who was chief of staff? Of these people, who had actually been there?”

Christ, it’s different in a jungle! You sweat, you get prickly heat, you have snakes. I fought in a jungle, and I thought it was awful. I mean, I’d never seen a jungle before I was in Sumatra. I remember when we were being overrun, going down a road with the jungle to the side. I went off the road because we were suddenly ambushed and I was frightened to bloody death — Japanese paratroopers were dropping all around me. I went about five yards into the jungle, and then I ducked, because the bullets were flying around. When I got up and walked back to the road, there was no road there. Jungles are unbelievable; you get so disoriented so quickly. If you’re a native, you know how to find north, south, east, west, in the jungle. You know that the sun side is dry and the other side is wet. I didn’t know that.

You lived in an Indonesian village for six months before your capture by the Japanese?

Yes. The officer that led the Japanese patrol that eventually picked me up was a young Japanese who had gone to university in the U.S.; he was educated at U.C.L.A. or U.S.C. I got to know him quite well over a period of three days. He was about my age, and there was a similarity in our backgrounds. He said he was from a samurai family. In a way, my background would be the English equivalent. This prompted him to offer to do me the honor of letting me commit seppuku-suicide. That would have been the honorable way to react to capture, according to Japanese custom. He wanted to lend me his gear — the white kimono and the swords. At length, when I was backed into a corner and said, “Thank you very much, but no thanks,” he got very irritable about it. Then he started the old slapping bit, and I was shoved into a proper jail and then eventually put with the rest of the POWs.

Have you seen any of the other survivors from the POW camp? Do you have reunions?

No. I don’t think anyone from Changi would ever have a reunion.

Nobody wants to remember it?

You’re opening not a can of beans but a can of vipers. If you dwell too much on those days, you are going to be consumed. There were very, very few survivors. One in fifteen survived.

What did you bring away from your prisoner-of-war experience?

I guess I learned what it is I really need in my life. As long as I remember being a prisoner in Changi, I will know that with a bag of rice and a knife, I can feed myself and my family for a sufficient time to allow us to regroup.

In Changi we had no choice but to look at ourselves. Truly. One day or another. I felt I was stripped of all my peeling, like an onion. This got stripped off and that got stripped off through the immoralities of the things that happened there — the starvation, the indignities, and all the death, all of this brought me to a realization of what I was, what I had to live with. All POWs got to this point at some time and then had to decide whether they could live with it or not. If they didn’t like what they found under all the layers, they died. A lot of people looked at themselves and didn’t like themselves and died. It’s very simple. We got to a point where we could almost predict, within a couple of weeks, when somebody was going to die. It was when they couldn’t stand any more of it.

How do the Chinese think of themselves in relation to Americans or Asia in general?

They think that there is a heaven where the gods live and that below that is the Middle Kingdom, where all Chinese live. The Chinese are the only ones who live in the Middle Kingdom. Below the Middle Kingdom is Earth, where everybody else lives — Japanese, English, Americans. So the lowest coolie would look at an American without envy. He might want our cars or clothes or money, but he looks at us and says, “My God, how awful to be one of those!”

So the Chinese think they are superior to Western men?

Well, they’re different. “Superior” is not quite the correct word. They have an attitude, a very particular, strange attitude. They say, “I’m sorry, but we live in the Middle Kingdom and you don’t.”

What is the difference between the Chinese and Japanese?

It’s like comparing apples and strawberries. They’re both fruit. Chinese are very practical people. They love to drink and eat, and they love the family. They’re loners. They like business, and they like making money, and money pleases them; they like to touch it. And their history is constantly with them. They’ll talk about a man like Ts’ao Ts’ao, who was a famous general, as though he were just around the corner, when he actually lived two thousand years ago.

The Japanese are a “group” people. They work in groups, they live in groups, they go on holiday in groups. They make group decisions.

Can you give an example of the different ways the Chinese and Japanese think?

Okay. There is a Japanese custom called shinibana, which is “death flower arranging.” Around cherry blossom time, they take a tree that’s maybe 30 years old, cut it just above the ground, and plant it in water. If it’s cut correctly, over a period of a few weeks you will see the tree give flower. The petals form and then fall, and the first of its green shoots come out — just a little way, because they haven’t got the strength to come out all the way since the tree is dead; the plant itself is dead, because you have cut off its life source.

Shinibana trees are very expensive. Perhaps as much as $40,000. They put them i.n the foyer of the hotels like the Okura and the Imperial. Japanese people will come from miles around, and they’ll say, “Ah so, so, so, so,” and they will bow to the tree because it’s so beautiful to thank it and the kami — the spirit of the tree. You see this 30-year-old tree, and you know that it’s given up its life for you. In its dying it has given you the privilege of being able to see infinity.

Now, the Chinese could not appreciate that. A lot of people would say, “How stupid!” and “What a waste!” But the Japanese understand the quality of it.

Do you see the Japanese or the Chinese dominating Asia at some time?

I don’t think so. I think that they can make a detente. You know, there’s no love lost between them. Their heritage has been one of conflict. The Japanese invaded China in 1931. A lot of people remember that. The whole Far East and Hong Kong remember the Japanese occupation. The Japanese were not good occupiers.

General Westmoreland said that the Asian people don’t value human life.

That’s total, absolute nonsense! It’s like some people used to say that the Japanese were different because they don’t get cold and can sustain themselves in the jungle. But it’s a matter of discipline, training. Japanese people would lose face if they said, “Jesus Christ, it’s cold.” We don’t give a shit. There is no discipline, unfortunately, or very little. It’s not found in the schools, it’s not found in the home, it’s not on the streets or in the people as it exists, say, in Japan.

Chinese or other Asian people, who live so close together, must be disciplined. Otherwise, everybody kills everybody. So they give “face” to other people. Face is manners, politeness. When a disaster happens, Orientals will keep their emotions inside. A terrible thing will happen, and you’ll see them laugh. It’s their only way of saying to the gods, “I’m a human being.” By putting on face, you don’t embarrass somebody else by moaning and groaning.

But it’s absolutely not true that they don’t value human life. They love their children as much as we do. They know much more suffering than we do, because the mortality rate is so awful there.

Where is the balance of power in the world today?

I think in the Far East. China vis-a-vis Russia vis-a-vis Japan vis-a-vis the U.S. And so on …. We are in the age of the Pacific.

We have forgotten that we are a Pacific power; we’ve forgotten that we are a mari-time power. Some twit has allowed our navy to fall to pieces while the Soviets are building up their war fleets and merchant fleets. Our merchant navy is not competitive now. The reason is supposed to be that American people get paid too much, their quarters are too lavish, and so on. Now, I believe that people should be paid as much as they can get — that’s our American system. At the same time, we need a solution. If you’ve got highly trained and highly paid crews, there must be a way to be competitive in the market.

In the transportation of bulk grain and raw materials, the Soviet merchant fleet is now very, very competitive because they can provide the ships that others want and pay their seaman whatever they want. The Soviets are becoming very open about their presence in Asia. They’ve got an aircraft carrier over there now. And the last administration has allowed our naval power to become vulnerable.

People will not realize that we have an opponent — Soviet Russia — and that the Soviets have laid down very clearly, in all their manifestos, in every speech that Brezhnev makes, in their Leninist and Stalinist gospels, that they are an expansionist country going all out for their particular point of view. They are our opponents, and they are in direct competition with us.

Is this a life-or-death competition, or is it more a matter of politics?

It is life and death. Look at history. That’s a big problem in America. Nobody looks at history; nobody knows anything about the past. There was a study done recently, by one of the major magazines, on foreign policy. They asked students some very simple foreign-policy questions. The results were astounding. The students knew nothing! When my youngest child was 12, she was asked in school where Denmark was. She thought it was a province of Canada! Foreign policy is not taught in our schools.

Do you think American businessmen understand foreign policy?

No. Let me give you an example. A friend in Taiwan called me one day and said, “I’ve heard that the Taiwanese government wants to buy two million cases of American six-pack beers. Do you think you could get any?” I was writing Noble House, and I was interested in the mechanics of export and import and the stock exchange, so I said, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out.” I was in California, so I tracked down the telephone number of Coors Beer and said to the Coors operator that I’d like their export department. There was a deadly hush. I said, “You know, exports. I want to buy some beer.” There was another deadly hush, and a secretary came on the phone, and I said, “Are you the export department?” She asked, “Are you a wholesaler?” I said, “No, listen … ” and I went into my pitch: “I want to buy two million cases of six-pack Coors, and we will pay American dollars, cash. How long would it take to get it to a port — Los Angeles — so that I can ship it out to Taiwan?” She said, “Oh, our beer doesn’t travel.” I said, “It travels all the way across the United States, so why shouldn’t it travel?” “Oh,” she said, “We’ve got more orders than we can fill anyway.” Click!

That could not happen in Europe, because 2 million cases of six-pack beers represents a lot of money — to Europeans. But Americans don’t think they have to get into export, because, supposedly, we have this marvelous, inexhaustible home market. But in the age of the Pacific, the balance of power is slipping out of our hands and is now centered in Asia, where you have China and Japan and Soviet Russia and Hong Kong and all those huge areas of untapped sources of materials.

Americans must begin to look abroad. We have a balance-of-payments problem. It is ludicrous to blame Japanese car manufacturers for it. It just happens that the Japanese manufacturers, learning from us, are selling goods that people want to buy.

You wouldn’t advocate restricting their imports into this country?

Absolutely not. To put a tariff on Japanese cars is undemocratic, and it doesn’t get at the source of the problem, which is that buyers prefer the Japanese cars. Nobody forces an American to buy a Japanese car.

Detroit manufacturers should have been able to forecast that American people would want a change, that we are on the edge of a new era. This is why I think President Reagan will be the right man to be president. Perhaps he can help us change into a people that says, once and for all, “Christ, there are other people out there. We’re going to turn ourselves into an exporting country!” If we turned ourselves around so that we looked inside our country and still looked outside our country, we would swamp the world with our technology, our workers our money, our expertise.

After all, most major inventions have been stolen by our opponents, the Soviets. They want our computers, our products. And the Japanese are just paying us their most enormous compliment. It is a custom in Japan that if you have an expert teacher — a sensei — who favors you, it is your duty to try to surpass your teacher. Japan is doing just that, and we’d better watch out. We are under siege economically. And historically, all wars have started for economic reasons.

You’re confident we can triumph?

Of course. Unequivocally. But we should not be afraid to learn from other people. After all, we have the best form of democracy there has ever been. Take Japan for a moment. In Japan the government, the tax system, and business all work together benevolently. The tax people are not the enemy, as they are seemingly here. We view the tax people as the enemy because they try to get the maximum they can out of every citizen. In Japan the overall attitude is “How can we make business work? How can we help business?” The people are employed by business. The primary difference between Japanese industry and our own industry is that Japanese companies believe that their major asset is their employees, and they believe their first duty is to their employees and their second to the stockholders. Japanese companies concentrate on making their employees happy. In America we mostly don’t give a goddamn. American stockholders say, “You’ve got to give us more dividends.” The Japanese say, “But that’s the wrong attitude.”

How did you feel about the United States’ opening relations with China?

It was a brilliant and wonderful and necessary thing. Of course, it did come at a time of their choosing, not of our choosing. They said, “Yes, we’ll be glad to see you.” It wasn’t just a miraculous thing or that suddenly Mr. Kissinger called them up and said, “Look, can I come to dinner?” Previous administrations had made probes, but the Chinese were not receptive until Nixon’s administration.

But then President Nixon, in his foolishness — and not knowing anything about Asia, for all his erudition — did not first inform our ally, the Japanese. The first they knew about it was when they read it in the papers. They even created a new word to describe their reaction — “shocku.” It was a matter of face — of manners.

You’re giving the Chinese as much credit for opening relations with the U.S. as Nixon or Kissinger?

Absolutely! This whole unnecessary mess started many, many years ago. In 1949 when Mao Tse-tung took over the mainland, both he and Chou En-lai — and this is a matter of record — asked to be allowed to come to the United States to discuss the whole problem. And they were rebuffed. Very shortly after that, when John Foster Dulles was secretary of state, there was this famous meeting — I think it was in Geneva. Mr. Chou En-lai went over to Mr. Dulles and put out his hand and said to him, “Mr. Dulles, may I introduce myself? My name is Chou En-lai.” And John Foster Dulles turned his back on him! Now that will be remembered a thousand years. Not only was it stupid, but it was really very bad manners.

Do you think that other nations see hope in President Reagan?

Yes. Of course, they’re praying and hoping, like we’re all hoping and praying for him. I think they hope for stability. Let’s face it: this high tax system which some twit economist has put upon us is tyrannical. It hasn’t worked abroad. Take England and its socialist theories. They just haven’t worked. In my opinion, any government that takes over 30 percent of your money is a tyranny. That’s why I love Hong Kong. Taxes there are 15 percent on money you make inside Hong Kong, and there is no tax on money made outside Hong Kong. One of the few things they tax is legal gambling-horse racing.

Why do the Chinese love gambling?

They want to make the killing. It’s the only way that they can get out from under. You bet a little to get a lot. A big winner won’t go blow it on a big car or a vacation. In Noble House, a coolie wins $10,000 and plans to buy a used plastic-making machine and some clothes for one of his grandchildren so she can become a dance-hall girl.

Gambling is the only legal way a poor person can make it fast, that is, if the gods smile at you. If they don’t smile at you, you lose. Maybe next time!

In Noble House a wealthy junk-fleet owner goes mad in a Mah-Jongg game and loses a fortune.

Yes, but don’t forget he was very peed off to lose! If you remember, he said, “Well, gods are gods.” Because sometimes the gods are on your side, and sometimes they’re not. Chinese theory is that gods and goddesses are like people: there is a fisherman god, a prostitute goddess, a madame god, a moneylender god, a bad god, a good god, a miser god, and so on. And like people, well, they go to sleep sometimes. You can pray all you want, but if the bugger is sleeping, he’s not going to hear you, so you don’t get your prayer answered. Maybe he’s out to lunch.

Doesn’t that sound like a pretty childlike view of religion?

Well, at least it’s a logical answer to why sometimes we win and why sometimes we lose. The Chinese are very practical people. They have an enormous awe and an enormous feeling for survival. They feel that they understand life, and they love life.

Although sadly having left us much too soon, as one might imagine, these fine books still exist at Amazon. It never hurts to support whatever people (or causes) James wished us to at this point. Karma can be good too.