Somewhere in the landmark townhouse that David Brock owns in Washington’s fanciest neighborhood, Brock still keeps the signed photographs and letters from the days when he was the literary idol of the capital’s conservative elite.

David Brock

But the dark, intense young author who became famous almost a decade ago as a journalistic hit man for the Republican right has since taken down from his walls most of those framed mementos. After all, the same prominent politicians and pundits who once praised Brock now revile him, because he has turned his memories and his skills against those outraged former patrons. He is what ever political movement should fear most; a turncoat who can write.

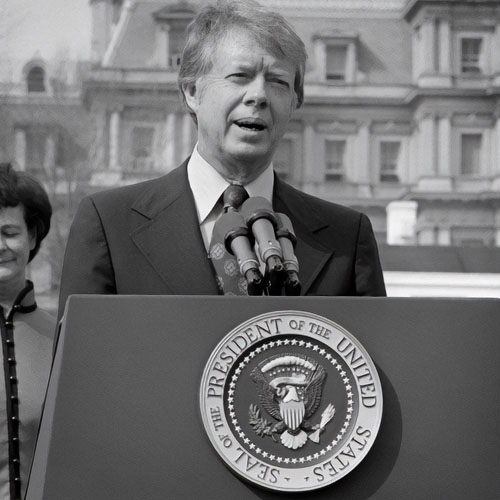

Brock’s first public break with his longtime cohorts came in the summer of 1997, when he wrote an article for Esquire denouncing the right’s ugly and unrelenting jihad against the Clintons. The following year he annoyed his former pals still more when he publicly apologized to President Clinton for writing the notorious “Troopergate” article that appeared in The American Spectator, where Brock was the star investigative reporter.

“Living With the Clintons,” from Spectator’s December 1993 issue, mentioned an alleged assignation between Clinton and a woman identified only as Paula — who, of course, turned out to be Paula Jones, later the plaintiff in the historic sexual-harassment lawsuit against the president. As Brock wrote in Esquire, not only did he no longer believe the Arkansas state troopers’ tales about the Clintons, but he had come to believe that the sexual witch-hunt against the president that was leading toward impeachment was both morally and politically wrong.

“Out in the country, I’m sure there are good conservatives who actually… practice what they preach. But I saw a pretty corrupt elite… saying one thing for public consumption and doing exactly what they wanted with their private lives.”

In his latest book, Blinded by the Right: The Conscience of an Ex-Conservative (Crown), Brock goes even further in criticizing both his own work and the machinations of what he calls “the Republican sleaze machine.” He now admits that he knew his defense of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in his best-selling first book, The Real Anita Hill, was wrong. He confesses that he lied about important facts in that controversy when he reviewed a rival book by journalists Jill Abramson and Jane Mayer. He also says, in an excerpt from Blinded by the Right that caused a firestorm when it appeared in Talk magazine last June, that he misused derogatory information provided by a Thomas associate to bully one of Hill’s supporters into retracting her testimony.

According to Brock, his deviation from the conservative party line dates back to 1995, while he was researching a biography of Hillary Clinton. What he had envisioned as a typically savage assault on the first lady and her husband took a different direction when Brock discovered that many of her enemies’ accusations were simply false. Most of his conservative fans were bitterly disappointed by the evenhanded tone of The Seduction of Hillary Rodham, which they had hoped would do severe damage to the Clintons during the presidential election of 1996.

In the wake of that book, old friends and colleagues shunned Brock, who took this rejection as a sign of the corruption of conservative values by hatred and deceit. Soon Brock found himself under the same kind of nasty attacks from the right-wing media that he had once inflicted on his liberal targets. Gossip columnists hinted, wrongly, that his head had been turned by a secret affair with a male Clinton aide.

At a moment when Brock was just starting to understand the implications of being a gay man in a movement hostile to homosexuals, his critics focused on his lifestyle as the reason behind his sudden treason. There was, as Brock says in Blinded, an element of truth in that explanation. His misgivings about homophobia on the right were confirmed when conservatives stooped to using his sexual orientation against him.

But it was Brock’s decision to emerge as a Clinton defender during the Monica Lewinsky scandal and the ensuing impeachment crisis that sealed the enmity of his former admirers. Following his apology to President Clinton for Troopergate, Brock became a key source for myself and other journalists seeking to uncover the covert activities of what Hillary Clinton famously termed “the vast right-wing conspiracy” against her husband. (In my case, Brock eventually became a personal friend as well.)

His revelations about the cabal of prominent conservative lawyers secretly advising Paula Jones, and about The American Spectator’s $2.4 million “Arkansas Project,” funded by billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife to dig up dirt on the Clintons, seriously embarrassed the president’s adversaries when Clinton seemed on the brink of political destruction.

As Brock considered his own culpability for the damage done by his slashing journalistic adventures, his critics on both the right and the left expressed their doubts about his motives for defecting. The uproar surrounding his newest book has provoked those same difficult questions. Some charge that he simply wants to attend hipper cocktail parties, that he hopes to escape his pariah status among the liberal establishment. Others insist his purpose is mercenary, that he has found another path toward career advancement and book sales.

Yet a few friends who know Brock well have observed the sometimes torturous process of self-examination he has endured while preparing the extraordinary confessions of Blinded by the Right. He has paid a heavy price for his decision to come clean about his past. Every reader will have to decide whether to believe a writer who admits that he once lied for a political cause. But whatever the ultimate verdict on his character, his veracity, and his sincerity, Brock’s memoir of his long journey through the underworld of the far right is both important and compelling.

During Clinton’s impeachment, “everything I had seen on the right for the prior six years started to make a horrible kind of sense… I came out publicly and said what I could about the right-wing conspiracy.”

Why did conservatives hate the Clintons so overwhelmingly?

There is an idea in Republican circles, after the two Reagan administrations and then the Bush administration, that it was in the order of things for Republicans to control the White House. So they viewed Clinton as an illegitimate usurper from the outset…. And the Clintons symbolized things larger than themselves or even their own platform — particularly Hillary Clinton symbolizing feminism — because they were the first two-career couple to be in the White House, the first baby boomers. They were somewhat wrongly associated with a lot of the cultural values of the 1960s, values that the right hated: sexual tolerance, sexual freedom, abortion rights. Beyond that, if you talk to a Clinton hater long enough, you’re going to find that the hate actually has to do with the emotional problems of the hater much more than it does with the Clintons.

But you dealt with a lot of people who you feel sincerely did hate them.

Take Bob Tyrrell [R. Emmett Tyrrell Jr.], the editor-in-chief of The American Spectator, my former boss. Here is someone who had a promising career that was consumed and destroyed by an irrational hatred of the Clintons. Why does someone who was capable of writing some fairly brilliant books earlier in his career do that? What you have in Bob’s case is baby-boomer self-loathing. He was very condemnatory of the Clintons, talking about how they represented the cultural erosion from the ’60s. And at the time, Bob was going through a very messy divorce of his own. What struck me was, you can say a lot of things about the Clintons but they kept their family together. And Bob wasn’t able to do that. One of the main themes of my book is how endemic hypocrisy was all the way around. Almost every prominent Clinton critic leading the impeachment effort had their own personal problems that were often much worse than what they were accusing Clinton of. I don’t have a really good theory to explain that.

In the book you suggest you knew that much of what Clinton s opponents did was wrong even while you were observing it all. What was the breaking point for you?

The breaking point in my mind — as opposed to when I was capable of going public with it — really came during the time I was researching my book on Hillary Clinton. Working on that book, I spent more time in Arkansas than I ever had previously, and became familiar with what I think is a kind of very gossipy, somewhat ugly political culture of homegrown Clinton-hating. I really changed my view, partly as a result of finding out that many of the accusations against them were flatly untrue. Before I published the Hillary Clinton book, before I apologized for Troopergate, there was the Gary Aldrich incident in the summer of 1996. Aldrich was the ex-FBI agent who had written a kind of a tell-all book about what he saw in the Clinton White House, [a book] that was really filled with errors. And what bothered me about that experience was that even after the mistakes and errors were exposed, even after Aldrich himself admitted that his main accusation in the book was merely hypothetical, he was still touted on the Wall Street Journal editorial page and by Rush Limbaugh as a truth-teller. That was pretty disturbing to me.

You exposed a phony anecdote in Aldrich s book, about Clinton going to the Marriott Hotel in Washington for sexual assignations.

I had firsthand knowledge of the smear that was being broadcast all over the country. I was trashed for revealing that, and [Aldrich] was celebrated. The [exception] was George Will, who called me before the ABC Sunday-morning show where Aldrich was making one of his first TV appearances. Will asked me what I knew, and I told him. And he did tear Aldrich apart on the air. He was the only conservative who took that position.

Did you hear from other people telling you privately to shut up?

Sure. One right-wing activist called me and said, “If [Aldrich] goes down, we all go down.” He suggested that I leave town for the weekend and stone-wall any questions. And the Wall Street Journal ran a drawing of a campaign button saying I BELIEVE GARY ALDRICH, after Aldrich himself admitted that the book was flawed…. I was extremely disappointed.

Your critics say you switched sides for notoriety and money How do you answer those accusations?

I’ve tried to be as honest about my motivations as possible. Their theory doesn’t make sense. First of all, I had a lot of success with the Anita Hill book. I had a lot of success and notoriety with Troopergate…. My career was going great. I had no expectation of making more money on the left than I was raking in on the right.

You were making about $200,000 a year at the Spectator?

Yeah. I was at the pinnacle of conservative journalism, so why would I want to switch for monetary reasons? As for my social life-conservatives have a chip on their shoulder, and there’s a lot of paranoia that they’re not as good as liberals, in the sense that they’re not as socially desirable. So there’s this argument that I wanted to get out of the right wing to attend more cocktail parties, to have a more glamorous life. [But] while I was struggling with the Hillary Clinton book, I knew that I was reviled in a lot of places on the left and among liberals. And then to pick Hillary Clinton as the subject — because many people on the left don’t even like Hillary Clinton — to me that doesn’t make sense either.

You indicate in your new book that there’s a huge gay underground on the right in Washington. Among the Democrats, most gays are out of the closet. Does conservative politics attract a certain type of gay man?

The closeted Republicans tended to be much more extreme and right-wing. I’m talking about people I know and also what I did. At a certain point you’re trying to prove yourself tough enough, and you think you’re not because you’re hiding this aspect of yourself, and you’re feeling that if [conservatives] ever find that out, they’re going to think you’re a sissy. You know, there are plenty of closeted gays in high-ranking positions there, and they are the nut-cutters, for lack of a better word — the more extreme, gung-ho types.

What’s interesting is that, historically, this issue comes up all the time on the right. Dating back to [onetime Communist] Whittaker Chambers, Roy Cohn, Joe McCarthy, and J. Edgar Hoover, there are many examples of important figures on the right who were or allegedly were in the closet.

Some of the best haters, I think.

Why do you think that is?

I think it’s self-hatred.

Does that still exist now?

Yes, it does. In my case I think there was a point at which I started to almost resent being gay when I was finally really making it in the conservative movement. I had published or was about to publish the Anita Hill book, and I could see that [being gay] was a stumbling block — and I had no gay life to speak of. So I think that what goes on — and this goes on in the closet, I think, in general, not only on the right — is that you tend to channel your emotional life into your politics. The rage that you can see in some of the other figures we mentioned and that I had in myself — I think some of that was misplaced or misdirected.

Are there members of Congress now who are still in the closet?

Oh, absolutely. Yes. And this became an issue for me, because there were closeted Republican members of Congress who were taking fairly aggressive stances on impeachment — which was basically an issue of a sex lie — who were themselves living lies.

Were you tempted to out them?

It’s an interesting question, because I think there will be some outing controversies surrounding my new book. I wasn’t tempted to out these particular members of Congress at that point. There are references in the book to a couple of them without their names.

Where do you draw the line on outing somebody?

I took it on a case-by-case basis. I really didn’t think to name everybody I know in Republican circles who is gay.

You talk about Matt Drudge in this book.

Yes. I thought he had practiced enough of a kind of outing of other people’s personal behavior [to make him] fair game. I’ve had some personal experience with him, and I tell that story in the book: We essentially go out on a date in Los Angeles and he takes me to a gay club and takes me dancing. He certainly navigated the gay strip on Santa Monica Boulevard in L.A. like a pro.

Drudge insists that although he hangs out in gay bars, he isn’t gay In fact he has denied vehemently that he is gay on several occasions over the past few years, including quite recently Is he in the closet?

I consider him to be in the closet, although he never appeared to be that way around me — but I think that he was tailoring his behavior for his audience.

In this book you reveal a strange faction fight over outing within the upper reaches of the conservative movement and Congress. Arianna Huffington wanted to out a top aide to Newt Gingrich in order to advance her own interests in the movement — which she too has since denounced and abandoned. Tell me about that comical incident.

In 1995 Arianna came back to Washington from her then-husband Michael Huffington’s lost Senate bid [in California], and reinvented herself as kind of the godmother of the Gingrich revolution. Within Newt’s inner circle she was jockeying for power against a guy named Joe Gaylord, who had been Gingrich’s closest political advisor and aide going back to the 1970s. Gaylord was a consultant to the Republican National Committee and to Gingrich’s PAC. He and Newt were extremely close. And Arianna wanted to, as she said, get Gaylord. Her strategy for getting Gaylord entailed first asking me to out him. I wasn’t interested in doing it, so ultimately Arianna wrote her own column in which she wrote about Gaylord’s “intimate friend,” who she named in the piece. The other ironic thing about this is that at that time, Arianna was still married to Michael, who had a homosexual past before their marriage, which she knew about. She would often ask friends of mine if I knew if Michael was engaging in any kind of gay activity during this period. So she was essentially bearding for Michael and trying to out Gaylord through me, and by that point I was openly gay and had almost been outed myself. It was a very odd set of circumstances [laughs].

Did you say, “Arianna, what do you think you’re doing?”

No, I didn’t. Unfortunately, I had a lot of avoidance strategies in place. I had a way of humoring people and avoiding things because I wanted to stay in the movement, I wanted to get ahead in the movement, and I didn’t want to rock the boat.

Somehow the mainstream press doesn’t seem as interested in scandals involving right-wing figures as it was in scandals about the Clintons, although it seems clear that the antigay leadership in Congress is being partially staffed by closeted gays. That seems to me like a potentially very juicy story, and yet it never reached the mainstream at all. Why is that?

Yeah, and the problems of [Republican Congressmen] Bob Barr and Dan Burton — the most exhaustive accounts of their hypocrisy in doing the same or worse than what they were accusing the Clintons of — was in Salon magazine. It was not in the New York Times exhaustively. And so again there was definitely… a lower threshold for what one could publish on the Clintons than for anybody else.

There’s an electrifying moment in the book when Troopergate is about to come out in the Spectator and you don’t know what the reception is going to be like. And suddenly CNN is on the air with it.

I literally almost fell out of my chair watching CNN lead with some pretty salacious quotes from that story. There was obviously a hunger for Clinton scandal, Clinton sex stories, that I guess went back to ’92 and Gennifer Flowers. This was a pattern… of right-wing pressure on mainstream media outlets to get these stories out.

Going back for a minute to the issue of sexual hypocrisy, my impression is that everybody in conservative Washington knew back in 1995, when Newt Gingrich became the House speaker, that he was having an illicit affair with somebody on the staff of another congressman. Did you know about that at the time?

Yes, I did.

“Closeted Republican members of Congress who were taking fairly aggressive stances on impeachment… were themselves living lies.”

Her name was Callista Bisek, and she never became a household word like Monica, but everybody in Washington knew, didn’t they?

Yes, they did. I have a specific recollection about that. I had given two pretty major parties in connection with the Gingrich revolution. One was on election night in 1994, and one was actually, I think, an even bigger party celebrating the first hundred days of Gingrich. And I distinctly remember at the hundred-days party that there was kind of hushed talk about whether Gingrich was going to be exposed — was Gingrich vulnerable now that he’s the speaker?

Did people know his girlfriend’s name?

I had heard about her and where she worked. I don’t know that I had heard the exact name.

Again, it’s amazing that important journalists in Washington on the right, commentators, politicians, knew for three years at least that Gingrich was carrying on an illicit affair with a person on the congressional staff. At the same time, they were backing him in his sexual crusade against Clinton.

Gingrich himself said he was going to say the word Monica in every speech in 1998, while he [himself] was involved with an aide.

Are there conservatives who take seriously the rhetoric of sexual morality, or is it all cynicism? Is it all just a way of using the rubes out in the countryside to achieve political objectives that have nothing to do with morality?

I write about this a bit in the book, partly as a way of explaining how I could participate in a kind of neo-religious crusade as somebody who is gay and who never believed the right-wing social-values rhetoric. The bottom line is that everybody around me was living according to a double standard. They were saying one thing for public consumption and they were doing exactly what they wanted with their private lives on the other hand.

You know several of the attractive conservatives who became commentators on television during the Clinton wars. Were they all the paragons of moral virtue in their private lives that they played on TV?

No, quite the opposite. I didn’t see the values that we as conservatives were fronting for being put into practice in Washington. Now out in the country I’m sure there are good conservatives who actually live and practice what they preach. But I saw a pretty corrupt elite all the way around in Washington.

A decadent elite?

Yes, absolutely, a decadent elite. For example, I had a conservative columnist, who is on television frequently, at the party at my house celebrating the Gingrich election in 1994. I had a bedroom on the second floor, where people had left their coats on the bed that night. And when I took him up to find his coat, he pushed me on the bed and tried to stick his tongue down my throat.

How closely tied is the George W. Bush administration to what we could loosely call the anti-Clinton conspiracy?

They’re pretty closely tied. Reading the Washington Post last January and February, and the column where names of people going into the administration were published, it struck me that to a large extent the Clinton wars were about winning these jobs, winning power…. I mean the [conservative legal organization] Federalist Society and Federalist Society members, starting with Ken Starr, with Ted Olson, and then all the way down to, below the surface, some of the lawyers who were doing the secret work in the Paula Jones case, all connected through the Federalist Society. They’re getting top jobs. Olson is solicitor general. At the Justice Department Office of Legal Policy is Viet Dinh, he’s a member of the Federalist Society, [and] Brett Cavanaugh, who is one of the deputy White House counsels and worked for Starr. The secretary of energy, Spencer Abraham, was a founder of the Federalist Society, and the cofounder is his general counsel at the Energy Department. If you look at the top legal jobs through the departments and in the White House counsel’s office, you ’d see a lot of Federalist Society connections, and also I’ve seen that a good number of [Bush’s] judicial nominations have been put forward essentially by the Federalist Society.

So it was a successful “conspiracy” in some ways.

It was. The [Clinton] impeachment was for me a major moment where everything I had seen on the right for the prior six years started to make a horrible kind of sense. And I was against impeachment and I came out publicly and said what I could about the right-wing conspiracy, and apologized for whatever role I had played in the Paula Jones case. I felt pretty good after the ’98 elections, because I really thought the Republicans [had betrayed] whatever was good in conservative philosophy, and they didn’t really deserve to be in power. I wasn’t the only one who thought the conservative movement had the wind knocked out of it by the end of ’98, and that by losing the impeachment battle they had lost the cultural war. But you know, they are back in a significant way. I have been in Washington since the mid-eighties during the Reagan administration, and I have never seen the conservative movement as excited and happy with a president as they are with George W. Bush.

Now that you’ve admitted to lying about Clarence Thomas, critics say that there is no reason to believe what you’ve written in your new book. How do you respond to that argument?

The questions about my credibility and veracity are completely understandable, since in my book, which will be out soon, I confess to lying and blackmail. The only alternative I have to telling the truth is to continue living with these despicable actions and have them eat away at me for the rest of my life. So I made a personal decision, not a career decision, that I can’t live that way anymore.

You may still acquire Mr. Brock’s book today, should you wish. In fine contemporay fashion, you will notice that the price of the digital book with zero physical printing, shipping, or storage costs associated with it will set you back more than twice as much as the physical Hardcover edition. Don’t you just love that? … On a much happier note, you may actually hear from Paula Jones herself in these very digital pages. (We don’t spend anything on ink for these stories either, although ours happen to be free.)